It is said that the period 1913 – 1919 was one of the most tragic in the historical development of the Macedonian people. With the peace agreement in Bucharest (August 10, 1913), Macedonia was divided among its neighbour Balkan countries. Two years later (1915 – 1918), its territory became an arena of military devastation and destruction. Macedonia continued to be an interesting sphere for the Balkans and European military-diplomatic and political interests that had been dictated for more than a century by the five great powers: Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, Germany, Russia and France.

The situation in Macedonia after the Balkan Wars and the Bucharest peace treaty contained favourable conditions for the involvement of the great forces from both blocs to strengthen their positions in this part of Europe. The ethnological landscape was very different, as the first wave of ethnic cleansing of 1912-13 had barely affected the earlier population data, but also the behaviour of the combatants evolved quite differently. First it was the priests, then the teachers, followed by armed mercenaries, then came the armies of Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia and finally, the five great powers. Shortly after the Balkan wars, there are troops of all kinds that operate each with their own laws and rules without counting Macedonians. How were these people to defend themselves from the on slot of one wave of occupiers after another?

The Macedonian Campaign of the Great War

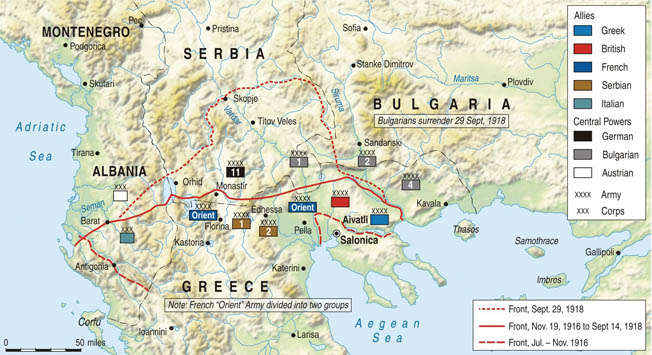

The First World War thrust the population of geographic Macedonia into a new and different set of wartime difficulties barely a year after the Second Balkan War ended in 1913. The Vardar region of Macedonia, annexed by Serbia in 1913, initially became a Serbian “home front” as early as 1914 as tens of thousands of males were mobilized and sent north to help repel the Austro-Hungarian invasion. But Macedonia itself soon became a battle front again. Bulgaria, Germany, and Austria-Hungary invaded Serbian (Occupied) Macedonia in 1915 while British and French troops tried to come to Serbia’s defense by landing in Greek (Aegean Occupied) Macedonia and trying to push north from there. Bulgarian troops also advanced well into Greek (Occupied) Macedonia in 1916 against the Entente forces there. By July 1917, Greece had officially joined the Entente.

Little has been studied of the Macedonian Front in relation to the central theatre of the Western Front. As well, Eastern Macedonia and the consequences of the German-Bulgarian occupation there (1916-18) were from the beginning the subject of special monographs and reports, but what happened in exactly the same period in Western Macedonia has had minimal published personal testimonies and unpublished archival material.

In order to understand the effect of WWI on Western Macedonia and almost all the cities, towns and villages, one needs to take a look at the “Salonika Expedition on the Balkan Front”, the reasons why the Balkan Front was started, and how it affected the region.

Attitudes Leading to the Balkan Front of World War One

- The French used the offensive in the Balkans against Austria-Hungary in the spring of 1915 as a solution to the deadlock of the Western Front.

- On 1 January 1915, the French envisioned launching a joint Anglo-French offensive with 500,000 men who would disembark either in the Adriatic or Salonika.

- The French wanted to extend their cultural and economic influence in the Eastern Mediterranean.

- The British also came up with numerous plans as to how to deal with the stalemate in the Western Front and agreed on Churchill’s idea of a naval attack against the Dardanelles.

- Venizelos, the Greek Premier promised that Greece would join the fray if: 1) Romania also entered the war. 2) Bulgaria maintained her neutrality. 3) Britain and France would provide two army corps.

- The Bulgarians intended to fulfill their territorial ambitions, the Germans however, considered Macedonia as a useful secondary theatre, where the Allies would divert manpower and material resources away from the Western Front.

- Whereas fighting was pretty much constant in Northern France and Flanders between 1914 and 1918, military operations in the Balkans followed a different pattern. Combat which took place in the region was more sporadic.

- Bulgaria, Greece, Romania and Serbia all followed their own nationalist agendas and joined opposite sides solely to attain their war aims. These countries usually wanted to realize their goals at the expense of their neighbours with no consideration towards the Macedonian people, especially in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars.

- Greece constituted a unique example of a state fractured by an internal political crisis (the bitter power struggle between King Constantine and his Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos between 1914 and 1917 being the prime and burdened by tense relations with the Entente. Greece maintained her neutrality, despite being occupied by Allied forces in Salonika, a diplomatic quandary which poisoned Allied-Greek relations until the removal of Constantine by the Allies in June 1917.

This fractured political crisis also had an effect on Greek businesses 7,844 km away in Toronto, Canada. Click here to read more about the “Anti-Greek Riots in Toronto Canada in 1918.

The Macedonian Campaign originated from opposite views held in London and Paris. The French had an interest for power in the Near East and wanted to check the aspirations of her Allies, Italy and Russia. France did not want Russia to be seen as the sole protector of the different nationalities in the Balkans. France also wished to halt Italian ambitions in the Adriatic and the Eastern Mediterranean, where Italy held territorial designs over Epirus, Asia Minor and the Dodecanese Islands.

By being involved in Greek politics, France supported Venizelos against King Constantine and wanted Greece to become a republic. Where as Britain was apposed to abolishing the Greek monarchy and favoured King Constantine. The British also considered the Balkan Front as an unnecessary distraction to the British war effort. A distraction, which would divert much needed manpower away from the Western Front.

The governments of Bulgaria, Greece and Romania (through their respective foreign policies) committed themselves in the war only to guarantee their territorial and nationalist objectives. They bargained with both the Central Powers and the Entente to reach these goals. Serbia… saved by the French and Italian fleets, and after a rest period in the island of Corfu, her soldiers went back to fight on the Macedonian Front.

Creation of the Macedonian Front – Third Balkan War

The First World War naturally became the continuation of the Balkans Wars and was called the Third Balkan War. On 12 October 1915, General Maurice Sarrail and the French disembarked at Salonica with the 114 Infantry Brigade. Salonica possessed a cultural and racial diversity with a mix of cultures, races, religions, and languages that he witnessed, in a city which, for more than four centuries, belonged to the Ottoman Empire. It was only after the Balkan Wars, and the Treaty of Bucharest of August 1913, that Salonica was formally attached to Greece. When the first Allied troops disembarked, the city had not yet been completely ‘Hellenised.’ From their arrival, the Allies imposed military rule over the ‘new territories’, including Salonika.

NOTHING GREEK ABOUT IT! SALONIKA – On 14 May 1913, in the aftermath of the Greek annexation, an Athenian officer, Hippocrates Papavasileiou, wrote to his wife the disgust that Salonica inspired in him:

- ‘I am totally fed-up. I’d prefer a thousand times to be under canvas on some mountain than here in this gaudy city with all the tribes of Israel. I swear there is no less agreeable spot’.

- On 19 May, he added, ‘How can one like a city with this cosmopolitan society, nine-tenths of it Jews. It has nothing Greek about it, nor European. It has nothing at all’.

- Papavasileiou’s tirade confirms not only his anti-semitism, but the fact that at the turn of the century, Salonica was largely a Jewish city. After their departure from Spain and Portugal in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the Sephardic community had profoundly transformed Salonica and made it one of the largest centres of Jewish life in Europe.

Salonica becomes, more than ever, a secondary front where soldiers had to fight against another enemy: disease, which affected nearly 95% of the men present in Greece and Serbia between 1915 and 1918 (nearly 360,000 victims). Dysentery, scurvy, venereal diseases affected many soldiers, and only treated by a small and poorly equipped medical corps. The major health problem in Macedonia was malaria, which developed rapidly in this area at the beginning of the century.

The region, ravaged by years of war was conducive to the rapid spread of epidemics of all kinds. It became very difficult to act in these conditions when a large part of the troops was hospitalized. Exceptional measures were taken to treat the sick but also to clean up the marshy areas, to overcome malaria in Macedonia. In the 1916 malaria epidemic was contained, and transformed the strategic situation in Macedonia.

The First World War in Macedonia, as on the Western Front, settled into immobile front lines and trench warfare for long periods of time. As was the case elsewhere in Europe, these conditions of stalemate produced a war of attrition and economic mobilization behind the lines. Military authorities and governments came to treat everything in Macedonia – agricultural land and crops, minerals, and the local population itself – as strategic resources to be assessed and exploited for their ability to contribute to the larger war effort. The resulting requisitions and economic restrictions led to severe material deprivation. These burdens were generally far more protracted and onerous for the civilian population than in the preceding wars.

The prolonged conditions of stalemate also changed the sort of war crimes and abuses suffered by civilians in Macedonia. During World War I, deportations now took place on a mass scale. Greece and its ally, France, continued to carry out internments and deportations that became so broad that thousands were eventually swept up in them. Bulgaria and its allies organized mass deportations for entire categories of civilians whose national loyalties were deemed suspect, as well as large-scale evacuations of civilians from front line areas. A large number of deportees were sent to labour camps where they faced harsh living conditions and suffered high mortality rates.

Internments and Deportations

In the case of the Macedonians conscripted into the Greek army that were stationed in Florina (Lerin), in 1916, the advancing German and Bulgarian forces forced the Greek officers to abandon their posts leaving the Macedonian soldiers without orders,. As a result, most left their posts to return to their villages. Upon hearing that the French were moving into the Florina region, many decided to return to their posts (barracks) in Florina. In one case, Giogi from Leskovits was arrested and sent to Marseille to work on the docks loading cargo ships for two years. Most Macedonians who abandoned their posts were sent to concentration camps in Crete and France.

A group of concentration camp inmates in France from Greek (Occupied) Macedonia emphasized not only the perceived injustice of their deportation but also its apparently extra-legal nature in their complaint to the French ministry of interior: We have been deported from Macedonia, exiled from our native land, far away from our homes by order of the Commanding General of the Armies of the East as dangerous to the safety of these armies. Our guests made us leave our country for reasons more or less trivial…. None of us has undergone during the course of [the war’s] existence a conviction of any kind, no one has appeared before a court martial despite the accusation that hung over us. Many were even sent to load cargo on the docks of Marseille in France for 2 years, the duration of the war and returned back at the end of the war.

The Muslim Nemir Ali from the village of Zelenich (Sklithro) in Florina after his return from eight-month exile in Marseilles was re-arrested in Kozani because he did not possess a certificate. Many other Macedonians filled applications to seek mediation for delayed passports (certificates).

French Requisition of Products

The armies of the Great Powers requisitioned supplies from civilian populations, committed atrocities against them, and exercised various forms of surveillance and control over them as well. But locals continued to refrain from violence against each other. Nor did they violently resist occupying forces even from a different ethnic group. Collaboration became the norm for survival to secure their most important priorities: economic well-being and local stability. Behind the front, armies were amassing supplies, building facilities and creating the conditions that could support a military population of half a million men. This is exactly what took place in the villages of Western Macedonia and especially in Zelenich (Sklithro).

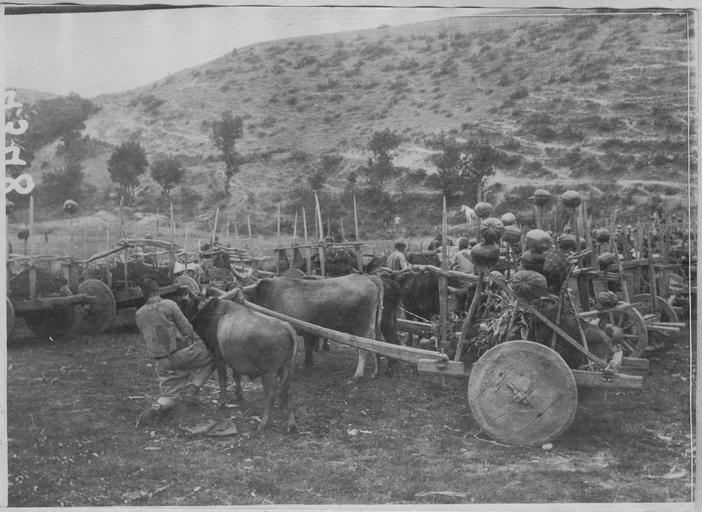

The French military authorities occupying central and western Greek Occupied Macedonia appear to have been more diligent to compensate local residents monetarily for requisitioned products but in reality, what was promised was not delivered. According to their own count, they still owed compensation to residents of the prefecture for over 12,000 requisitioned cows and buffalo, 2,200 horses and mules, and 2,700 sheep. Residents in the village of Emborion (a little over 1,000 residents) awaited compensation for over 1,700 cows or buffalo. The French owed compensation for almost 3,900 cows or buffalo taken from Kailari, a small town of around 4,000 residents. For the village of Zelenich with over 2,000 people plus a contingent of 1,000 French, 300 Serbian and 300 Italian soldiers, we can just imagine how the war affected the livelihood of the civilian population.

A pamphlet of 1918 entitled L’oeuvre civilisatrice de l’armée française en Macédoine (The Civilizing Work of the French Army in Macedonia) written by E. Thomas presents the French army’s work as civilizing (in Macedonia). He discusses the extensive road-building project undertaken by the Allies. The road network built under the French and British, he reported, totalled 1,300 kilometres and would finally “permit the complete exploitation of [the region’s] resources.” Similarly, he proudly described projects that dramatically increased the supply of potable drinking water (canals and an entire aqueduct were built), increased the productivity of local salt and lignite mines, eliminated malarial mosquitoes and swamps, and increased agricultural production to the benefit of producers in addition to the armies whom they supplied.

The images of buffalo drawn carriages are just one example of the procurement away from civilian to military use. This had a profound impact on the ability of civilians to feed themselves. The French had engaged in ‘modern’ agriculture, especially market gardening, replacing the ‘prehistoric wooden plough with a metal one, and had shown the locals how to use new agricultural methods to increase production. Because fighting was more sporadic they set up brick-works, a tobacco factory, conducted a geological survey and organized mining and discovered reserves of lignite in the Kailari (Ptolemaida) area. Many swamps were drained including areas around Lakes Zazari and Hematida.

The Presence of Foreign Armies in Macedonia and Zelenich

The French Army not only produced crops and vegetables on its own account but also sought to introduce modern equipment and teach ‘new’ methods to local farmers. The soldiers set up their own brick-works so they could build defences on the front line and facilities (such as fountains) in the rear. They established a kiln to make earth pipes to conduct water and large jars to hold it. Since Zelenich was behind the front lines, the regiment helped build fountains with earth pipes throughout the whole village. The village did have a kiln just above the area around St. Demetrius church but there is no evidence whether that kiln was built by the French or it existed before. One thing we do know is that the kiln was used well into the 1960s and some of the homes in the village had running water in there cold cellars. One in particular was the home of Yani Tsesmegis who bought the house from an indigenous Muslim villager in 1923.

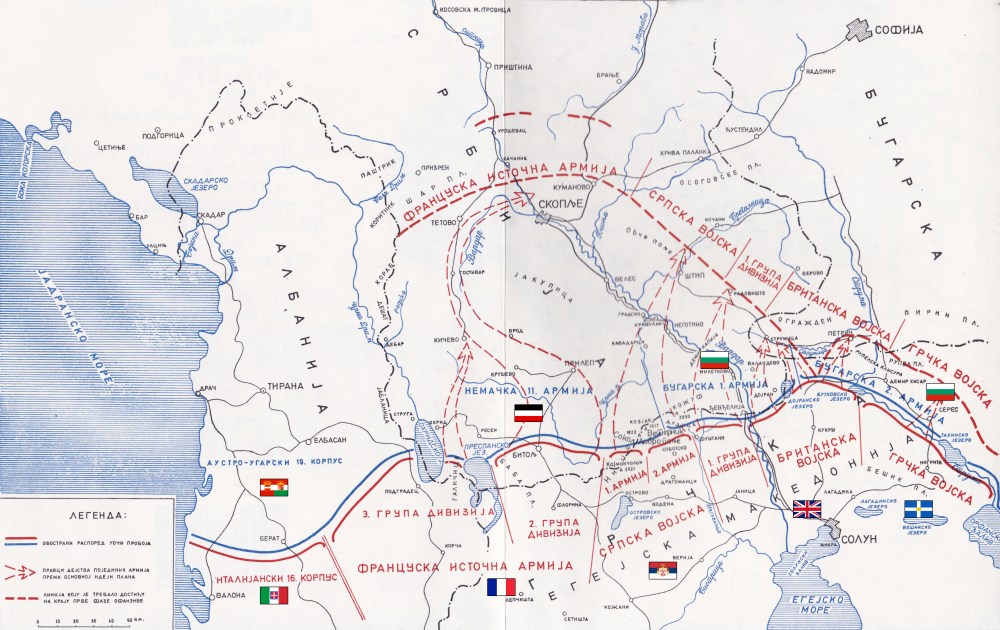

During the First World War, a multinational Allied force of French, British, Serbian, Italian, Russian and Greek numbering 500,000 troops faced the Bulgarian Army and German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish units, totalling 300,000 men. A considerable part of the French and British corps was made up of colonial troops: Senegalese, Algerian and Indochinese skirmishers, Moroccan spahis, Zouaves and Madagascans, Indians, Maltese and Cypriots.

Hundreds of thousands of men from several countries, including colonial territories, coexisted for three years with the indigenous Macedonian population with very different practices and habits compared to the experience of Western soldiers and officers.

Back row (l to r): British, French colonial, Indian, Italian, Serbian. Front row (l to r): French Senegalese, French, French Indo-Chinese marine. The troops on the front row are flanked by two Montenegrins. This photograph was taken prior to Greek forces joining the Allied cause. Courtesy of the Salonika Campaign Society.

Thus, in the multitude of camps created by the Allies in Macedonia to prepare and defend the front. In addition to the military preparations, and the fact that combat in the region was more sporadic, one could indulge in or attend sports competitions (running, swimming, boxing, football, rugby, cricket for Britons, etc.), to gymkhanas, horse shows, military parades, marching bands and musical concerts, as well as several theatrical, pantomime, circus performances.

Soldiers in Zelenich:

- One Regiment of French soldiers (1,000)

- One Battalion of Serbian soldiers (300)

- One Battalion of Italian soldiers (300)

The activity that was most closely associated with the Army of the East was gardening, and the maintenance of vegetable gardens on the front growing potatoes, red beans, cabbage, cauliflower and other vegetables. The practice was so widespread in the French and British armies that it earned its members the nickname of “gardeners of Salonika”. Oral traditions express the work of irrigation and discovery of springs carried out by the French army.

Mount Gradishta and the Oak Forest

The bare area of Mount Gradishta above the village once had an old growth oak forest that was cut down by the French to supply to amass supplies to construct bridges, build facilities to house soldiers thus, creating the conditions that could support a military population of half a million men. The green northers area is known as Rideau, and this pine forest was planted by students of the village in the 1950s to prevent erosion. In the early 1920s, the gully to the south (right side) of the pine forest was created by a massive rainstorm which resulted in a land slide enveloping half a dozen Muslim home, killing five people.

The Potato and Zelenich

The French presence in Zelenich was obviously very evident with the encampment of over 1350 soldiers in the village. Besides housing the soldiers, feeding them included soldiers engaging in growing their own food and assisting the locals in producing more themselves. The cultivation of the potato is said to have been spread by the French in Zelenich and the rest of Macedonia.

giving employment to the Macedonian women.

The potato was transported to Europe by the Spaniards in the early 16th century and then spread to Portugal, Italy and the rest of mainland Europe. The first written evidence of the importation of potatoes into Europe is a receipt dated 28 November 1567 from a potato exporter from the Canary Islands to an Antwerp merchant.The systematic cultivation of potatoes began only after 1771-1772, the period when there was a great shortage of grain, while at the beginning of the 19th century the cultivated areas had increased significantly throughout Europe.

The potato entered the Balkans 1699 in the town of Baja (Hungary) as it was mentioned in a customs office. It then appears in Slovenia between 1730 and 1740 and is used to feed cattle. Over time, however, better types of potatoes arrived from the Croatian coast, so in these areas, from the middle of the 19th century, potatoes, along with grain, will be the most important field fruit, which will remain to this day.

By 1787 the Serbian County of Bačka, official documents indicate the sowing of potatoes was already quite advanced. At first, peasant farmers are coerced to plant the crop but soon accept the potato realizing its benefits. By 1800, potatoes become registered in many other regions of Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Eventually the potato reaches Western Macedonia being brought there by Muhajirs (Slavic speaking Muslims) from Bosnia. Potatoes were known in Istanbul since 1835 and in 1847 Ottoman Sultan Abdulmejid donates money and potatoes to the Irish during the “Irish Potato Famine” of the 1840s. At the World’s Fair in Paris in 1855, Turkey exhibited potatoes from Bulgaria.

Oral history traces the potato to the village of Zelenich around the middle of the 19th century. The time of the economic expansion in the region. The fact that the village had two “Pazzars” every week is indicative of the trade of goods that passed through the village. It was more popular than Florina itself with only one “Pazzar.”

Military Justice Macedonia and Zelenich

By March 1917 the French ordered the disarmament of the local population. The army … issued a three-day deadline for residents to turn over any weapons they still held, “any person found in possession of weapons, regardless of whether or not he is the owner, [would] immediately be executed by firing squad.” In Zelenich, the 2nd floor of the Nitsev house was used as a court room (they brought in the chairs from the school) where they had a trial in which they convicted 20 Macedonian men and 2 women in chains from the Prespa region. They were taken to an area called Rideau (at the foot of Mount Gradishta) where they shot.

Accommodations in Zelenich

Officers behind the lines could often arrange their own accommodation. In Zelenich a French officer used the 2nd floor of the Nitsev house. They even used the 2nd floor “Chardak” – open area as a courtroom. In 1917, they had a trial in which they convicted 6 Macedonian men for possessing arms. They were taken to an area called “Porio” where they shot and buried.

Diaries, Correspondence, and Photographs of French Officers & Soldiers in Zelenich

Effect of French Occupation on Local Population

The blockade imposed by the English and the French on the regions of Kastoria, Florina and Korytsa results in hunger from the disruption of supply and the consequent rise in prices. The Allied control over vital parameters of the local economy and administration further disrupts the means of locals to survive. The requisitioning of school buildings throughout the district by the Allied Army, French, Italian and Russian, materially impeded the normal operation of the schools.

The compounding of problems relating to the assimilation of speakers of other languages in the Macedonian region: Within three years the people of this district have moved from a Greek occupation to a German-Bulgarian, and from there to an Allied (French and British) and back to a Greek, with the result an uncertain position with regard to the education of their children. According to some informants of Zelenich, this uncertainty prevented the celebration of seasonal cultural and religious events.

The sentiments in the non-Greek-speaking population of this district was played by the passage through it of the Bulgarians, who proclaimed that they had come to liberate them from their Greek servitude. The destruction of the material infrastructure of the Macedonian schools by the Greeks after the Balkan Wars was now further destroyed by the French in order to meet the needs of the Allied Army (e.g. chopping up desks in the school in Armenochori for firewood for French troops. In Zelenich, the French also cut down the whole western side of mount Gradishta to the construction of barracks, bridges and firewood.

Macedonians in Foreign Armies

Macedonians were mobilized in the Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian armies in a way, that is, by force and terror. The number of Macedonians mobilized in the Greek army was significantly smaller due to the presence of the Entente forces and the fact that mobilization in Greece was carried out later. However, the terror and the bad treatment of Macedonian recruits during the mobilization did not differ from those of the Bulgarians or the Serbs. That is why Macedonians deserted the Greek army as they deserted from the other occupational armies.

Macedonians in the Aegean part of Macedonia had already had bad experience with the violence of the Greek authorities, and had already heard about the mobilization in the other parts of Macedonia, so, many of them left or hid in the mountains. These are the reasons why only 20,000 Macedonians were mobilized by the Greek army at the beginning of the war. The Macedonians fought in almost all armies of the Entente and the Central Forces.

Macedonian deserters from the Greek and the Serbian army who went to Bulgaria were not only engaged in the Bulgarian army in the first front lines, but they were also used for manning the German army. On October 30, 1916, the Minister of War sent an order to the chiefs of the division districts according to which the best 2,000 Macedonians were selected and sent to Prilep for manning of the 11th German Division. In this way, the Macedonians fought in almost all armies of the Entente and the Central Forces.

The Macedonian Issue & the French

During the First World War both sides of the war paid more attention to resolving the Macedonian issue, recognizing the need for more accurate knowledge of the national identity of the Macedonian population. For that purpose France hired a team of French scholars and experts in the field study of Aegean Macedonia, who concluded that the local population is not either Serbian, not Bulgarian, and at least not Greek, but a separate Slavic people with their own language and with other national attributes. As one of the possible solutions to ensure lasting peace in this region proposed creating an independent Macedonia under the auspices of the Allies.

The French interest was quite understandable, among other things that the main front of the Balkans stretched on the territory of Macedonia. Starting from this interest, by the French government in Macedonia was referred to qualified experts from various scientific fields: historians, linguists, ethnologists, hydrologists and others experts, most professors from the University of Paris and other scientific institutions. This numerous scientific staff was actively assisted by the French military intelligence service.

Edmund Bouchier de Bell – General Staff of the French Eastern Army of The Balkans

He had the opportunity to stay in Macedonia for a long time during the First World War. In 1918 Bouchier de Bell made his observations published in the book entitled: “Macedonia and the Macedonians” (“La Macédoine et Les Macédoniens ”), in which he writes about its geographical position and interest of Europe and the Balkan states to rule its territory. He writes that Macedonians have their own speech which is neither Serbian nor Bulgarian. The book also gives an overview of the nationality of Macedonians, emphasizing that “… the Slavic population in Macedonia should be separated as a separate nationality whose name it would be Macedonian Slavs, or, for short, Macedonians … ”

Rene Picard, “The Autonomy of Macedonia” – 20th July 1916

The famous French scholar and expert on the “Macedonian Question,” Rene Picard, prepared an extensive study entitled “The Future of the Balkans,” and added the concept of an “Autonomous Macedonia” (“La Macedonie autonome”) that is neither Serbia, Bulgarian and certainly not Greek in ethnology, linguistics, folklore, and politics.

- “If we asked the Christians of Macedonia they would answer that autonomy was the most desirable solution for them”

- “There is and, in fact, there has always been a Macedonian spirit in Macedonia”

- The Christian population in the country side … is known to be neither Bulgarian, nor Serbian

- “The autonomy of Macedonia and the constitution of a Balkan federation would have most ardent advocates among the citizens of Salonika, especially among the majority of the Jewish population”

- “One can very well see Salonika in the future as a free city, the capital of autonomous Macedonia and the centre of the Balkan federation”

- “The Bulgarians themselves admit that the Macedonians differ from the other Bulgarians”

- “The Macedonian politicians in Sofia are feared; many Bulgarians of old Bulgaria would be glad to see the Macedonian Bulgarians return to Macedonia. They accuse them of taking everything away from them, their jobs and privileges.

Having spent about ten months on the Macedonian front, Rene Picard, certainly one of the experts on the Macedonian Question, wrote a pamphlet entitled “The Future of the Balkans” in which he particularly stressed that an autonomous Macedonia was the only solution to the Macedonian problem.

Edmnond Bouchie De Belle on The Macedonians – La Macedoine et les Macedoniens, Paris, 1922, 80, IV, 303.

Edmond Bouchie de Belle, born 23rd August 1878, Doctor of Law, was a high financial official in Paris, advisor at the Ministry of Finances, and during World War I occupied a prominent position in the Headquarters of the French East Army in the Balkans. In this way, de Belle had the opportunity of spending a substantial period of time near the great bend in the River Crna, following the movement of the Army in the vicinity of Lake Ostrovo, Lerin, Bitola, Prilep and finally, Skopje, where he died on 20th October 1918. During his stay, de Belle wrote a book about Macedonia, which was printed posthumously in Paris under the title La Macedoine et les Macedoniens (Macedonia and the Macedonians), 1922. De Belle’s book, which was given an award by the French Academy of Sciences, is interesting and significant from several aspects. Here are a few extracts from the book.

“The population is different in nationality according to its origin and has long since been an object of the tactics of influence by the neighbouring Balkans states, with the support of the Great Powers, the interests of which have been linked with the situation in the Balkan countries. Macedonia is populated by three groups of nationalities. One of them is the disputed nationality of the Macedonian Slavs, or briefly, Macedonians, which comprise the core of the rural population.

Then follow three other nationalities which aim to dominate the Macedonians – the Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks – and still another three nationalities detached from the dispute – the Wallachians, Turks and Jews. But none of these nationalities populates a defined territory, but appears here and there throughout the country. In all the fields of Macedonia there is a nationality of peasants with a Slav language and of the Orthodox religion.

The Bulgarians consider them as being their own “in language and heart,” even citing the Greater Bulgaria, created by the Treaty of San Stefano and the name “Bulgarians” under which the victims of the Treaty of Berlin fought against Turkish oppression.

The Serbs consider them as “Serbs”.- since Dusan’s state formerly included “the whole of Macedonia,” according to the manuscripts surviving Turkish subjugation, and since the language was allegedly “Old Serbian” and since the Macedonians celebrated the family “slava” or Saint’s day. In spite of the fact that they bear some similarities in their character, faith and language with the Bulgarians and the Serbs, they differ from both.

Finally come the Greeks, according to whom neither the origin nor the language are of decisive significance, but only the “spirit” and culture, which are allegedly Greek; just as no one can say, for instance, that the French are not Latins, so, too, no one can say that the Macedonians are not “Greeks.” It is obvious that the Macedonian Slavs are not Greeks.

You may ask a peasant from the district of Ostrovo, or Bitola, what he feels himself to be, and in nine instances out of ten, he will answer you -Macedonian! Accordingly, the Slav population of Macedonia should be considered as a separate nationality, the name of which would be Macedonian Slavs, or briefly, Macedonians …”

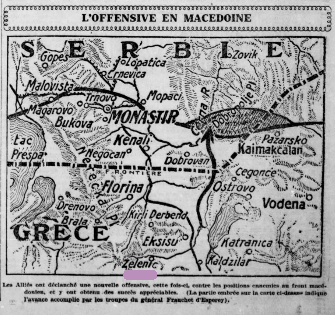

Final Attack of the Allied Army of the Orient

In September 1918, the Allied troops led by French General Franchet d’Esperey overthrew the central powers and conquered the current territory of the Republic of (North) Macedonia. The current territory of the Republic of (North) Macedonia was the battle scene between the Austro-Hungarian armies, German, Bulgarian and Turkish, on the one hand and the French armies, English, Greek, and Serbian on the other. Thus, the current territory of the Republic of (North) Macedonia was one of the most affected territories in the action of the Macedonian Front. The cities: Bitola, Dojran, Gevgelija, Kukush, Ohrid, Prilep, Krushevo were almost completely destroyed during the War.

THE GREEN SHADED AREA SHOW THE VILLAGE OF ZELENICH.

The conflict ended in November 1918. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was in tatters. Russia, withdrawn from the war after the 1917 revolution, lost ground. A brief kingdom, composed of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, became Yugoslavia, the country of the Slavs of the south Vardar Macedonia. Greek territory extends into Aegean Macedonia and almost as far as Constantinople.

At the end of the First World War before the Macedonian subjective forces stood a new conference for peace in Paris. It was to set the question of how to avoid Bucharest, as well as how to present the aspirations of the Macedonians. For its part, the situation in Europe before the upcoming peace conference in Paris is important differed from the situation in Bucharest. After the wars it was quite clear that Europe together with the Balkans is no longer what it was before the beginning of the Balkans and the First World War. All this in anticipation of The Paris Peace Conference, but also because of the political situation in Bulgaria and the situation of tens of thousands of Macedonian refugees, fostered hopes, and encouraged the work of defending Macedonian rights to life.

Actions on this plan were also made by various companies on The Macedonians with whom the last steps were taken to convince Europe in the right of Macedonia to be a united, free and equal state in a Balkan federal democratic republic. In this regard Macedonian intellectuals in Switzerland were especially active. Organized in political societies, which were part of one General Council based in Lausanne, they held conferences sent memoranda to the great powers, published a magazine, fought for free and indivisible Macedonia, in its ethnic and geographical economic borders. The Macedonian political society was the most active “Macedonia for the Macedonians”, which had its own rule book and statute. The idea preoccupied almost all prominent figures of the liberation movement because it was the only possibility to re-win the unification of the already torn Macedonian people.

In this direction was the adopted Declaration in four points on The Serres Revolutionary District, under the leadership of Jane Sandanski. In the third point where the necessity of the territorial unification of Macedonia as a guarantor of the peace of The Balkans wrote: “The territorial unification of Macedonia is not an act of hostility towards the free Balkan peoples nor violent and separatist erosion on their territory. She will renew at the expense of all as a rounded geographical unit and will be a jointly invested capital for the common good of these peoples which it will only unite them for a life of peace, sincere cooperation and happiness of the future. ”

However, the Macedonian problem at the Conference did not receive any attention. The conference did not take into account the demands of the representatives of the Macedonian national movement, nor the memoranda sent by by progressive European circles. One such memorandum on the 26th February 1919 was addressed to the British Government by James Boucher, a famous journalist and publicist, who at the time of the Paris conference advocated for a proper solution to the Macedonian issue. In his 9-point memo, Boucher stressed the need for the formation of an autonomous Macedonian state and demanded protection of the country from the great powers because only in that way: “… the population will be able to take care of their own interests and to live and to progresses without the harassment to which it has been subjected so far.”

The Macedonian people were put in a paradoxical situation of being represented by the governments of states that were only interested in the annexation or division of the territory of Macedonia.

In 1919 the Paris Peace Conference sanctioned the division of Macedonia made at the Bucharest peace agreement. And this time the “European” powers, under the pretext that they could not handle the Macedonian issue, so they allowed the it to be cut up and divided.

Sources:

Artaria & Co. Publishing. (1890). French Troops in Western Macedonia (Florina/Monastir) [Map]. 25 centimes bleu Semeuse camée Petit essai de monographie . https://semeuse25cbleu.files.wordpress.com/2013/05/bitola_map_1890.jpg

Belle, E. B. (2017). La macedoine et Les Macédoniens (Classic reprint). Forgotten Books.

Bregu, E. (2013). The causes of the Balkan wars 1912-1913 and their impact on the international relations on the eve of the First World War. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2013.v4n9p115

Broucke, K. (2021). Perceptions and realities of the Mediterranean East: French soldiers and the Macedonian Campaign of the First World War. British Journal for Military History, 7(1), 23. https://bjmh.gold.ac.uk/article/download/1470/1582/

Broucke, K. (1919). “TRIUMPH IN THE BALKANS” ANGLO-FRENCH CO-OPERATION IN MACEDONIA DURING THE FIRST WORLD WAR. Fisher Unwin,. https://www.academia.edu/8840640/Triumph_in_the_Balkans_Anglo_French_Co_operation_in_Macedonia_during_the_First_World_War?auto=download&email_work_card=download-paper

Broucke, K. (2021, March). Perceptions and realities of the Mediterranean East: French soldiers and the Macedonian Campaign of the First World War. British Journal for Military History. https://bjmh.gold.ac.uk/issue/view/114/BJMH7%2C1

Cheminsdememoire. (n.d.). The Eastern Front: 1915 – 1919 [Picture]. Cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr. https://www.cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr/en/eastern-front-1915-1919

Clarke, J., & Horne, J. (2018). Militarized cultural encounters in the long nineteenth century: Making war, mapping Europe. Springer.

De Belle, E. B. (1918, September 18). La Presse “La Macédoine et les Macédoniens” [Newspaper Map]. Numerique.banq.qc.ca.https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3197676

Eötvos Loränd University – Budapest. (1912). The Armies of the East WWI [Map]. Histoire-passy-montblanc.fr. http://www.histoire-passy-montblanc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/2a-front-dorient-region-de-monastir-edessa.pnghttps://semeuse25cbleu.files.wordpress.com/2015/02/secteurs-postaux-front-dorient-recc81gion-de-monastir-edessa.png

Esposito, V. (General – West Point). (1959, January 1). Salonika Front 1916 [Map]. Wikimedia. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/57/Serbia-WW1-4.jpg

Gallica. (1916). Maps of Macedonia (1904-06 & 1916). https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8446090f?rk=21459;2

Gounaris, B., Llewellyn-Smith, M., & Stefanidis, I. (2022). The Macedonian front, 1915-1918: Politics, society and culture in time of war. Routledge.

Histoire-passy-montblanc. (1917). The plain of Monastir and its mountain ranges [Map Photo]. histoire-passy-montblanc.fr. https://www.histoire-passy-montblanc.fr/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/5a-plaine-de-Monastir.jpg

France24, director. YouTube/ Reporters : Le Front D’Orient, Prélude à La Victoire De 1918, YouTube, 13 Nov. 2018, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lmZwzmM1vs. Accessed 4 July 2022.

French Foreign Legion. (2020, May 10). Foreign legion in the Balkans: 1915-1919 | French foreign legion information. French Foreign Legion Information. https://foreignlegion.info/foreign-legion-in-the-balkans-1915-1919/

Gadmer, F. (1916, July, 9). Macedonian Christian and Muslim Prisoners [Photograph]. pop.culture.gouv.fr. https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/memoire/APOR057984?listResPage=11&mainSearch=%22L%27armee%20d%27orient%201915-1918%20Salonique%22&resPage=11&last_view=%22list%22&idQuery=%22ceef6cd-f207-3c28-7d41-8bd8454cd7d%22

Kaiserlich-Königliches Militär-Geographisches Institut (Vienna). (1906). Macédoine. Gallica. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b53121098r/f1.item.zoom#

La Presse. (1918, September 18). L’Offensive en Macedoine. La Presse, p. 1. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3197676

Les Passerands de l’Armée d’Orient en 1917 « culture, Histoire et Patrimoine de passy. (n.d.). Culture, Histoire et Patrimoine de Passy. https://www.histoire-passy-montblanc.fr/histoire-de-passy/de-la-prehistoire-au-xxie-s/la-guerre-de-1914-1918/les-soldats-de-passy-en-1917/les-passerands-de-larmee-dorient-en-1917/

Markezinis, S. (1913). Balkans in 1913 [Map]. commons.wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a4/Balkans_at_1913.jpg

Military Map (Unknown Author). (1918, September). Military plan of armies on the ground for Vardar Offensive 1918. Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/6/68/%D0%9F%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD_%D1%81%D0%BD%D0%B0%D0%B3%D0%B0_%D0%B7%D0%B0_%D0%BF%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BE%D1%98_%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%83%D0%BD%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B3_%D1%84%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B0_1918.jpg

Off Road. (n.d.). Macedonia 1912-1918. Macedonia 1912-1918. https://macedonia1912-1918.blogspot.com/

Opérateur, K. (1915, December 14). The buffaloes of the French military intendancy [Photograph]. pop.culture.gouv.fr. https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/memoire/APOR026207?listResPage=6&mainSearch=%22L%27armee%20d%27orient%201915-1918%20Salonique%22&resPage=6&last_view=%22list%22&idQuery=%226c5e07b-7e3d-372-1026-f64181ae4e14%22

Opérateur K. (1916, May 6). The buffaloes of the French military intendancy [Photograph]. pop.culture.gouv.fr. https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/memoire/APOR070431?mainSearch=%22%20Gr%C3%A8ce%2C%20Mac%C3%A9doine%20occidentale%2C%20L%27armee%20d%27orient%201915-1918%22&last_view=%22list%22&idQuery=%22f68626c-078f-4bdc-7406-8dbabdd7528%22

Opérateur, K. (1916, September 26). Old Pesosnitsa [Photograph]. pop.culture.gouv.fr. https://www.pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/memoire/APOR070403?mainSearch=%22%20Gr%C3%A8ce%2C%20Mac%C3%A9doine%20occidentale%2C%20L%27armee%20d%27orient%201915-1918%22&last_view=%22list%22&idQuery=%22acbe26-0b82-114a-2b63-8fa1ef4e0fe%22

Orient Front. (n.d.). Short History of the Macedonian Front of WW1. DISCOVER REMEMBRANCE OF THE MACEDONIAN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR. https://www.frontorient14-18.org/en-us/

Papaioannou, S. S. (2012). Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918.https://drum.lib.umd.edu/bitstream/handle/1903/13631/Papaioannou_umd_0117E_13792.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

PIEGAIS, G. (2018, 15). The Russian expeditionary force in Macedonia, 1916-1920 Fighting and mutinies on a peripheral front. Google Translate. https://enenvor-fr.translate.goog/eeo_revue/numero_12/le_corps_expeditionnaire_russe_en_macedoine_1916_1920_combats_et_mutineries_sur_un_front_peripherique.html?_x_tr_sch=http&_x_tr_sl=fr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

Rene Picard – Les Archives du Ministere des affaires etrangeres (Paris). Guerre 1914-1918, Balkans,

Shapland, A., & Stefani, E. (2017). Archaeology behind the battle lines: The Macedonian campaign (1915-19) and its legacy. British School at Athens – Modern Greek and Byzantine Studies.

Six, R. (2016, November 7). The War in the Balkans [Map]. Warfare History Network. https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/gardening-in-salonika-world-war-i-in-the-balkans/

Wikimedia (Unknown Author). (1937). Salonika Front WW1 [Map]. Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Salonika_Front_WW1.jpg

Website Links on the Macedonian Front of World War One

DISCOVER REMEMBRANCE OF THE MACEDONIAN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR