The demographic history of the village of Sklithro dates back to the signs of human settlement found in Lake Zazari more than 8,000 years ago, dated back to 6500 BCE at the beginning of the Neolithic era in Europe. This settlement was located above the present-day “Banja” which was called “Seblatsi/Sebaltsi.”

From that point on, the area around Lake Zazari played an important role in the evolution of the human societies and the land on which they were living, particularly in the “Four Lakes” region. This area still functions today in the production of a range of quality agricultural products and pastoral farming.

The geographical configuration of the Macedonian region, with the deep corrugations of its mountain terrain, the high peaks, the frequent alteration between mountain areas and plants with a Mediterranean climate provided for a mixture of farming practices.

During the Ottoman period (1380s – 1913), a complex system of land tenure was established. Large estates called “chiflikia” were established in the lowlands, where whole villages would lose their farmland and used as slaves to produce crops for the state. It is not known whether this is what transpired in the town of Seblats/Sebaltsi but, according to oral history, the inhabitants revolted against the Ottoman and as a result, heir settlement was destroyed.

As a result of this conflict (1385-6), the inhabitants of Seblatsi/Sebaltsi fled to the mountains for safety. The destruction of the settlement resulted in the formation of the villages of villages of Aetos (Ajtos), Agrapidies (Goricko), Nymfeo (Neveska) and Sklithro (Zelenić). They remained hidden in these locations for almost 100 years.

The next stage of migration occurred when the Yuruk Turks entered the valley and settled in Zelenić. This most likely occurred after 1481, the year if the first documented census (defter) of the village. Interestingly, on that census (1481) we have the numeration of three (3) Muslims. Therefore, the influx of Muslim migrants occurred earlier than previously known.

After the 1480s and up to the 1800s, the village and the valley was being cleared and populated with new migrants. Some of the first may have been Vlachs roaming the mountain ranges with their flocks of sheep/goats who may have settled in the village. For the most part, the Christians and the Muslims lived apart separated by the “Stara Reka” (old river) as they both struggled to survive.

The 19th century was the time of labour mobility of men within the Ottoman Empire and this saw waves of refugees after uprisings against the Ottomans.

From the early 1800s we have the successful revolts of the Serbs (1805) to the north and the Greeks (1831) to the south. As a result, Muslim reprisals and atrocities in the Balkans increased towards Christian communities in Epirus and western Macedonia. This forced thousands of people to migrate to safer locations.

These locations included the Zelenić-Sklithro valley with the founding of the villages of Lehovo-Eleovo, Asprogia-Strebrano. Neveska-Nymfao was originally formed by settlers from Seblatsi/Sebaltsi (Macedonians) but they were inundated by Vlach settlers who came from Moskopole (present day Voskopoje, Albania). Most of these new settlers in Neveska-Nymfao wre merchants and craftsmen who were not your typical Vlach sheepherders.

Major Migration 1850 – 1913: The phases in the movement of people from Zelenić-Sklithro

Phase One:

The first one was during the Macedonian Awakening in the village when economic conditions allowed villagers to migrate to urban centres. With increased agricultural production, families had the ability to increase their socio-economic status and trade with the outside communities in the region. The village had two weekly bazars which brought more people to sell their goods as well as use the 23 water mills to grind their grains.

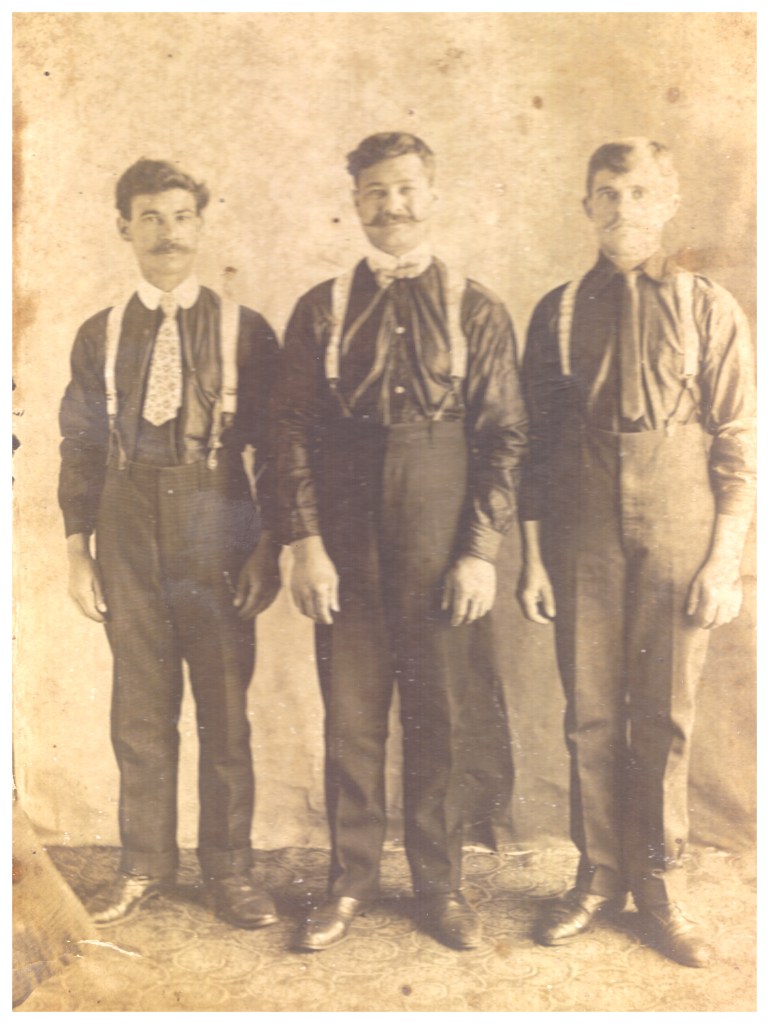

Traditional Pechalba (migrant workers)

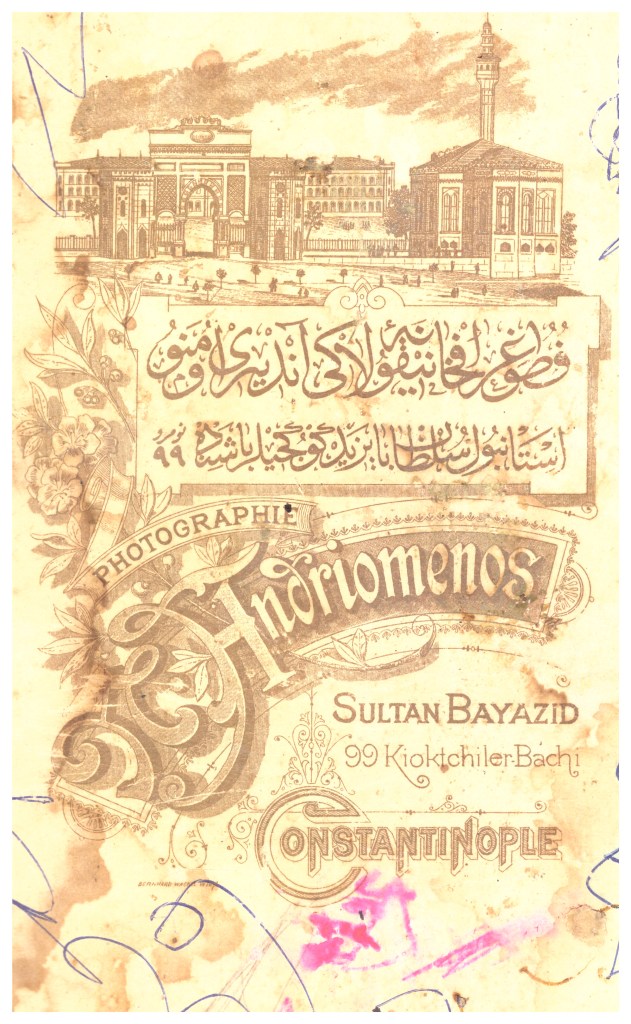

As a result of the co-habitation with the Muslims in the village, bilingualism allowed villagers to go further out into the bigger urban centres and attain a skill in various trades such as butchers, milkmen, bartenders, tailors, etc. They would then send for their relative to join them and many would eventually settle permanently in cities such as Istanbul, and Varna.

Traditional pechalbaor (gurbet – gypsy wanderer in Ottoman) was seasonal and clearly male labour migration. The Pechalbari worked typically in seasonal/temporary pastoralism, sheep breeding, as farmers or craftsmen.

Many men would travel as migrant farm workers in the big ćifliks planting and harvesting crops. They used to leave their home villages after St. George’s Day (6th May), perceived as the beginning of the spring-summer season, and return after St. Demetrius’s Day (8th November), the end of the harvesting season.

Late autumn and winter were the time of the most important family celebrations –weddings, or baptisms, and even symbolic funerals (migrants who died abroad were symbolically buried and lamented for in their family villages

For the numerous young men among the pechalbari, migration was a kind of initiation. Not only did they return with the earned amount of money but also with new experiences gained through “having been in the world.” Then, during the time of return to their home places, pechalbari had the opportunity to meet their future spouses. Macedonians in the mountain regions were strictly endogamous, thus engagements as well as weddings were organised exclusively in the home villages. They would come back to the village and marry someone from the village.

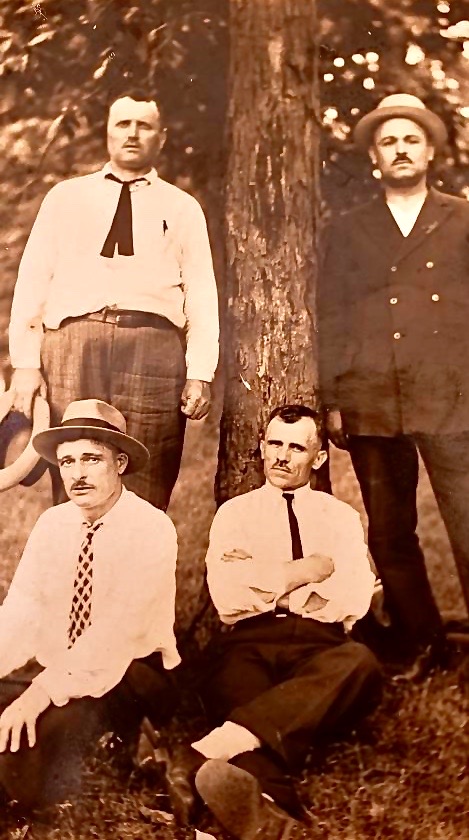

The increased socio-economic status also allowed prominent families to send their young men to school in the newly independent and autonomous states of Serbia, Greece, Rumania and Bulgaria. These young men would return to the Macedonian villages as priests, teachers, and skilled tradesmen. Some like Vani Pliakov (Steve Pliakes grandfather) came back to Zelenić as a teacher. Others would be influenced by their new-found freedom and came back as revolutionaries in the quest of freeing Macedonia from their Ottoman oppressors.

Of all the places for work, Istanbul was the most popular for people from Zelenić since most were bilingual and had an easier transition in attaining work. Once some of the first men had a foothold in the city, they would send for their spouses, family and friends to join them. The people from Zelenić with other Macedonians from the Kostur (Kastoria) region were instrumental in building St. Stephan Orthodox Church in 1857.

in 1870 the Turkish Sultan by a firman (imperial edict) announced the establishment of an independent Bulgarian Church. This prompted most Bulgarians to leave Istanbul and settle in the newly autonomous state of Bulgaria.

The Iron Church of St. Stephan (1899) was built by Macedonians from western Macedonia many of those from Zelenić and the Kostur and Lerin region. Descendants of these Macedonians still live and attend this church to this day.

After the Kresna-Razlog uprising (1878-1879) politically motivated migrations and refugee waves dominated as a result of insecurity and terror, uprisings, propaganda, wars and international decisions. Macedonians migrated to Bulgaria in the 19th and early 20th century after numerous uprisings against the Ottoman Empire and later after the Balkan Wars. One of the most popular destinations among the refugees was the Bulgarian city of Varna.

One of the first individuals to travel overseas looking for work as a Pechalbar (migrant worker) was Vani Chicules. He ended up going to North Dakoda (Railhead) in the 1890’s before he had children. Once he made a little money he then went back to the village where his first two boys would be born, Mike (1896) and John (1898). A lot of men who went to Railhead as sojourners, were from K’lari (Ptolemaeda) and they stayed and married local women, this is according Helen Chicules (granddaughter of Vani) who spoke to a few of the men from Railhead at Peter Evans father’s funeral Alec Evan (who owned Primrose Donuts). Even after 50 years, they still considered themselves Macedonians.

The end of the 19thcentury and the beginning of the 20thcentury again saw economic migration, especially to distant countries –first men, then whole families emigrated to Australia and Canada, and –to a lesser extent –to the United States (especially after the introduction of quotas in the 1920s).

Phase Two:

The second one was after the Ilinden Uprising (1903) when people left their houses in order to protect themselves against terror and repressions. Luckily, Zelenić did not have to face the devastating loss of life and property that other Macedonian villages went through such as Zagorichani (Basiliada). When the Ottoman army came to burn down the village, it was the Muslim people of Zelenić that spoke out against such a reprisal. As a result, The Ottoman authorities exiled five of the IMRO leaders to Anatolia and rounded up 50 men who actively took part in the revolt and sent them to prison in Monastir (Bitola). A year later, these 50 would end up tunnelling their way out of prison. Many would end up going to Bulgaria, others returned to the village and a few would become the first to go overseas. Many of them would end up in place like Canton and Cincinnati Ohio, other would go to Indianapolis Indiana. The flood gates were now open, the stories of prosperity were filling the letters being sent back home.

The Chicules were on the move again but this time Vani and his son John (Eftim) who would be one of the first to arrive in Canada from Zelenić. According to his daughter Helen, Vani changed his son’s date of birth from 1898 to 1896 so he would be older and qualify to travel as a 16-year-old to Canada in 1910.

Vani’s granddaughter’s Helen and Hope could not understand why the Chicules men travelled to many places. “First, it was dedo (grandfather) to Istanbul, then America (USA). Then he would send his sons out to bring more money. When he couldn’t make it in America, baba (grandmother) would send money to bring him back. Then his father sends him (John – Helen & Hope’s father) to Canada and when he couldn’t make it there, baba sends money to bring him back to the village. If they had enough money to go back and forth why were they going out to look for money?” The reason was to make money to buy more property in the village. So, her grandfather (dedo) comes back to the village and leaves his son in Canada. According to Helen, Vani was not a worker (farmer) he was always looking for ways to make money but the real smart one was her Baba Maria (Grcheva), “who could fool the Turks to not pay taxes.”

In Canada the biggest group of Macedonians lives in Toronto (between 80,000 and 150,000). The early 20thcentury migration from broader Macedonia to Canada is characterized as mainly political, as it followed the unsuccessful 1903 Ilinden uprising against the Ottoman Empire. Many Macedonian migrants found jobs in Toronto (particularly in metal industry), from which they progressed to owning restaurants, grocery stores and butcher shops.

The largest concentrations of Macedonians in Australia were formed in Melbourne (17,286), Sydney (11,630) and Wollongong (4,279 –about 1.6% of the Wollongong population).

Phase Three:

The third phase was after the Balkan Wars and the First World War. This time it was dominated by overseas migrations and traditional pechalba. It was a time of migration to distant countries, like Australia, the USA or Canada. The pre-Balkan War migrations overseas attracted post-war migrations to destinations with known contacts.

After the Balkan Wars, under the signed convention between Greece and Bulgaria (November 1919) for exchange of populations, tens of thousands of Macedonians from Greece were forced to leave their homes. Many families were split up due to the fact that those who chose to leave did not want to be turned into Greeks so most went to Varna, Bulgaria.

The massacre of thousands of Macedonians due to the two wars, the delineation of new boundaries, ethnic cleansing in the form of population exchanges forced movement of Macedonians, compelled more people to emigrate from Macedonia. Zelenić saw more people leave for Bulgaria, then the USA, Canada and Australia to a lesser extent.

Once again, Zelenić was out of harm’s way during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and WWI 1914-18. In both war periods, fighting occurred away from the village. According to John Voltsev(tsis) he did not remember any fighting in the village region during the Balkan Wars and during WWI a French battalion was stationed in the village as reserves ready to be diploid to the front.

Phase Four:

Following World War I, ethnic violence mounted in Greece as thousands of Macedonians (labelled as Bulgarians), mistreated with violent acts and instead protecting these minorities in Greece, the League of Nations attempted to resolve the tension for the benefit of minority protection. This concern turned into an effort to eliminate the Macedonian minority in Greece by forcing a population exchange between Greece and Bulgaria under the guise of the 1919 Treaty of Neuilly

According to the November 27, 1919 Minority Treaty convention, Greece expelled some 53,000 (Wilkinson, 1951:262) “Slav speakers” Macedonian Exarchists to Bulgaria in exchange of 30,000 so called “Greeks” Macedonian Patriarchists from Bulgaria. Many families from Zelenić were forced to leave the village while others decided to go on their own and move to Bulgaria.

The Greco-Turkish war of 1919 to 1922 and the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) was a major pivoting point for Greek Occupied Macedonia. As a result of Venizelo’s “Megali Idea” a policy to create a “Greater Greece” and bring together all “Greek peoples” under a single Greater Greek State, the Macedonians in Greece again became victims of yet another war. First it was Macedonian men sent to fight and die in Turkey for the glory of “Greater Greece” and later Macedonian lands were given away for the Turkish refugees.

The selection criteria for the population exchanges were based strictly on religion. In other words, Greece agreed to accept a Christian population regardless of ethnicity or language. Similarly, Greece agreed to expel a Muslim population regardless of what ethnicity it belonged to and what language it spoke. As a result, Greece exiled many Macedonians from Greek occupied Macedonia simply because they were of the Muslim faith.

Phase Five:

From 1919 to 1939, most of the migration of people from Zelenić- Sklithro was for the USA through Ellis Island in New York. To a lesser extent

Phase Six:

The sixth wave of mass migration was after the World War II (1939-1945), and the Greek Civil war in Aegean Macedonia (1946-1949) and this was connected to the aggressive immigration policies overseas (Canada, Australia and the USA).

After the civil war in Greece (1946-49) thousands of Macedonians were evacuated, fled or were expelled. These were the people who had joined the war on the side of the Greek communists with under the Slavic-Macedonian National Liberation Front (SNOF). Many from these Macedonians would end up in the Eastern Block communist countries and were not allowed to return to their birthplace unless they rejected their ethnic Macedonian identity and swear an oath to become Greek.

In 1947 those who had fled from Greece lost their citizenship. This meant that the exiles and refugees were unable to return to the land of their birth. Many of the refugees remained in Eastern European countries, especially the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary or Czechoslovakia, or left for the West. Some of them decided to move to Macedonia (at that time the Yugoslav Republic). It should be noted that amongst Macedonian scholars this refugee wave is not called “immigration” but “return.”

During the Greek Civil War, the village of Zelenić was not impacted by actual fighting between the two groups. The “Guerrillas” (communists andartes) would enter the village a night to attain food supplies, while the “Royalists” (army) would enter during the day looking for “Guerrillas” hiding from the army. Knowing that they could not capture/defeat the communists, the “Royalists” started moving villagers from the war zone in order to prevent them from supporting the communists.

Whole villages were moved including Sklithro-Zelenic, which was split between Amyndao and Petres. At the same time, the “Royalists” moved thousands of children to southern Greek, away from the war zone. The “Guerrillas” did the same in areas that they controlled, and these kids were moved to “Eastern Block” communist countries. Since Sklithro-Zelenić was located in a valley and was not easily defensible, the “Guerrillas” did not have control of the village so, the ‘Royalists” moved the whole settlement. Under the guise of safe keeping, both sides indoctrinated the children with their own propaganda. Some of the children from Zelenić ended up in southern Greece but most of them stayed with their parents in Amyndao and Petres returning after the war.

Those who could not return were the fighters of SNOF, not only were they branded as communists (which most were not), but they were also labelled as “Bulgarian.” The Greek government (Royalists) did not recognize them as ethnic Macedonians and as a result, used this tactic as a way to not allow them to return. Whereas those who were not ethnic Macedonians and fought on the side of the communists, were allowed to return. It was recorded that 57 families ended up leaving and settling in communist countries.

The 10 years of war had destroyed the economic infrastructure of the region. With a lack of opportunities, and the aggressive discriminatory policies of the Greek government towards Macedonians, young people began moving on-mass for better economic opportunities and cultural freedom. Another factor that influences the destination was the Macedonian communities that already existed in these places hence, Canada became a major location to settle. This flow of migrants continues right to the end of the 1960s.

Another major wave of emigration had been departures of men as guest workers (gastarbeiters) to Germany, and to a lesser extent to Austria and Switzerland during the 1950s and 1960s

Phase Seven:

The next, seventh wave, covers the period from the end of the 1960s to the end of the 1970s. The major factor was the political instability in Greece with the “Dictatorship Years” of the 1967 to 1974. Many young men left the village fearing they would be conscripted into the military. The dictatorship was characterized by right-wing cultural policies, restrictions on civil liberties, and the imprisonment, torture, and exile of political opponents. Macedonians were an even greater target during this period. Once again, the favourite destination was Canada, while some chose Western Europe.

Phase Eight:

The eighth wave of migration from the village occurred after 1981 when Greece officially joined the European Union. With open borders and entered the Euro-zone in 2001 with a common currency. This opened the door for whole families to migrate to where there was work.

Phase Nine:

Starting in the 1990s Albanians begin to settle in the village.

Sources: