The armistice of 11 November in 1918 is credited for ending the fighting of the First World War, but just twelve days prior, the Allied Powers and the Ottoman Empire signed the Armistice of Mudros. The Ottoman Empire was to be partitioned among the Allies, with all powers sending contingents to occupy Constantinople. As part of the deal, Greece received the city of Smyrna.

Armistice of Mudros, (Oct. 30, 1918), pact signed at the port of Mudros, on the Aegean island of Lemnos, between the Ottoman Empire and Great Britain (representing the Allied powers) marking the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I (1914–18). Under the terms of the armistice, the Ottomans surrendered their remaining garrisons in Hejaz, Yemen, Syria, Mesopotamia, Tripolitania, and Cyrenaica; the Allies were to occupy the Straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosporus, Batum (now in southwest Georgia), and the Taurus tunnel system; and the Allies won the right to occupy “in case of disorder” the six Armenian provinces in Anatolia and to seize “any strategic points” in case of a threat to Allied security. The Ottoman army was demobilized, and Turkish ports, railways, and other strategic points were made available for use by the Allies.

In April 1919, six months after the end of hostilities in WW1, Greece was issued a mandate at the Paris Peace Conference to occupy western Asia Minor to protect Christian communities from further atrocities by Ottoman authorities. Hellenic forces occupied Smyrna in May 1919.

The Asia Minor Campaign and Disaster (as the Greeks called it) cannot be treated as an isolated historical event, but in its relationship with the international developments of the time and their effects in the Near East and in Greece itself. According to the Greek elite, Greece was summoned by the Peace Conference to occupy Smyrna in order to secure order. This reasoning however, completely hid the truth about the causes and deeper intentions of planning and implementing the Campaign. The Greek ruling class thought that they would secure territories for her under the pretext of the existence of Greek populations in Asia Minor.

May 11, 1919 – New York Times – Macedonian Settlement

President Wilson’s “14 points” speech at the Peace Conference in Paris, with the USA unequivocally being opposed to Greek claims in Asia Minor, where in the 12th point an explicit and categorical refusal to the possibility of dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire was expressed. He also expressed for the expediency of an independent Macedonia. Italy was also opposed to Greece receiving Smyrna as it was also planning to expand its possession beyond the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean since France and Great Britain had promised to cede the Asia Minor coastal territories to Italy.

On May 15, 1919 Greek troops landed in Smyrna and the war began. Reports soon circulated that untrained volunteers committed acts of violence against Muslims. Rumours of such brutality enraged an already growing revolutionary faction within the Ottoman Empire led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. According to ΚΚΕ, then ΣΕΚΕ (Greek Communist party) – “in Asia Minor we fought not for the emancipation of slave brothers, but as mercenary gendarmes for the interests of English imperialism, who was interested in the Straits and the oils of Mosul.”

Smyrna was a wealthy city inhabited mostly by minorities in the Ottoman Empire: “Greeks, Jews, and Armenians.” Other than the Jews and Armenians, the reference for “Greeks” did not indicate Greek Orthodox by ethnicity but by religion. For Greece, the city was more than just a prize for participation in World War I. It validated the Greek foreign policy goal of capturing Constantinople and reviving the Byzantine Empire, or “Greater Greece” as they called it.

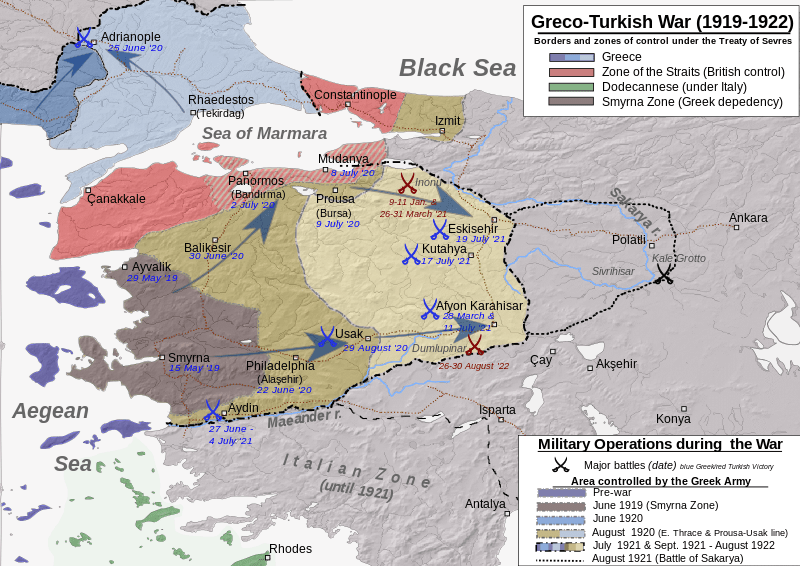

Initially, the Greek Army’s intent was to secure the region surrounding the Smyrna occupation zone, but by the summer of 1920, Greek forces eyed Ankara and began to push deep into the heart of Anatolia. Britain backed this move into Turkish lands because it saw the Greek military as a conduit to crush Kemal’s revolutionary movement. By October of 1920, Greek troops had gained control of northwestern Anatolia. This advance, however, was met with staunch resistance.

Turkish revolutionary forces using guerrilla warfare slowed the Greek Army’s progression, and Greek soldiers’ acts of violence against Muslim villagers created fear and panic and fuelled ethnic conflict. In acts of reprisal, revolutionary forces brutally murdered Greek Orthodox villagers and forced many others to migrate east to the Greek occupation zone.

The violent acts against civilians committed by both sides did not go unnoticed by the international community and spawned numerous humanitarian relief campaigns. As the fight dragged on, the Greek public grew weary of the war, and troop morale declined rapidly. Greek desertions soared. Britain, anxious about the perceived instability of the Greek government, withdrew its support. Then, the Soviets began providing munitions to the Turkish revolutionary forces in an effort to check Western expansion and turned the tide of war in favour of Kemal’s forces.

By 1921, the Greek advance had stalled. The Battle of Sakarya in August saw heavy losses for the Greeks and was a strategic victory for the Turkish National Movement. According to oral history, Macedonians were always assigned to the front lines defending against Turkish assaults. For the Greek forces, this defeat completely halted any hope for advances and sent shock waves through the government in Athens.

Sakarya was the beginning of the end for the Greek campaign. The Greeks were forced to begin a slow retreat toward Smyrna. By August 1922, 100,000 Turks were pitted against a disorganized Greek contingent of 200,000. The military operation lasted 24 days and essentially crushed the Greek army, forcing the Greek troops to the coast. The Offensive concluded when the revolutionary forces entered Smyrna and the city erupted in flames.

Thousands of Christian refugees, as well as Ottoman Turks fled in horror, jumping into the sea to escape the fire. It took nine days to extinguish the fire, and nearly 100,000 people perished in the flames as the great Ottoman city of Smyrna was reduced to ash. It was the end of the Greco-Turkish War and of a vision of a Greater Greece.

With the war over, the international community started peace negotiations. Britain, France, Italy, and others leading the peace talks decided that a compulsory population exchange was necessary to prevent the deaths of more innocent civilians.

With the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, 1.5 million Orthodox Christians and 400,000 Muslims were forced to leave their homes. This population exchange put tremendous financial pressure on an already destabilized Greece, as the country had to care for 1.5 million new refugees. At the same time, it created financial issues for Turkey since many wealthy families were required to leave their homes and cross the Aegean.

The exchange solidified the idea of both Greece and Turkey as homogenous nation-states. Although there were still minority communities left out of the exchange, Greece essentially became an Orthodox Christian nation, whereas Turkey became a Muslim Republic. This war and the concept of religious homogeneity still causes tensions between the two countries today.

Implications for the Muslim Population of Greek Occupied Macedonia, Zelenich and the War in Anatolia

After the end of the two Balkan Wars and the First World War, the Greek state doubled its territory and population. Many of the residents in these newly occupied areas were neither ethnic Greek nor Christian Orthodox. The Muslims who lived under Greek control prior to the Anatolian War were people of different ethnic and linguistic backgrounds (Turkish-speaking, Macedonian-speaking, Vlach-speaking, Albanian-speaking, Greek-speaking, etc.) as well as members of various Muslim orders.

As Greek forces advanced and established control over these areas, they implemented policies aimed at Hellenization and assimilation. Muslims in the occupied territories, including Macedonia, faced pressures to assimilate into the Greek cultural and religious framework. Greek authorities enforced policies that sought to suppress Islamic practices, promote Greek language and culture, and encourage conversion to Christianity.

Muslim institutions, such as mosques and religious schools, were often targeted and, in some cases, converted into churches or repurposed for other uses. Muslim religious and cultural practices were restricted, and the use of the Turkish language was discouraged. This cultural assimilation policy was part of a broader nation-building project undertaken by the Greek state.

There is little known about the Muslims who lived in Zelenich so, how did the Anatolian War of 1919-1922 affect their everyday life as well as their relations with the people of the newly formed Greek state? Stories from our grandparents indicate that overall, life with the Muslim villagers was peaceful but how did their lives change during the war? Were the Zelenich Muslims treated as the enemy by their follow villagers or the new Greek occupiers? These Muslims lived with their fellow Macedonian neighbours for over 400 years as a minority in a Christian village but, the Anatolian War would change this completely.

In Zelenich, Christians and Muslims lived in peace even during the periods of active Macedonian resistance towards Ottoman economic and political hardships. It was the Muslim villagers that saved 50 Christian men from being executed for their involvement during the 1903 Macedonian Ilinden Uprising. They were sent to jail in Monastir (Bitola) instead. The view that a Muslim might be a Greek national did not become the main criteria of acquiring Greek citizenship, being Christian was the only criteria. This was opposite to the traditional Ottoman millet system where all people in the Empire were allowed to rule themselves under their own laws.

Nationality was not founded on religious basis but on the material and moral interests throughout the empire. Presently, many nations were founded and consist of adherents of different denominations. Only the barbarous nations identified religion with nationality. During this period of occupation and assimilation, the Greek state deprived political rights from non-Christians and those Macedonians Christians who refused to convert to the Greek Eastern Orthodox Patriarchy.

Eastern Greek Orthodoxy was acknowledged as the established religion of the country and any other known religion was not tolerated. They forbid any form of proselytism or interference with Greek Eastern Orthodox affairs, while at the same time they allowed the Greek Eastern Orthodox to proselytize or interfere with the internal affairs of other Christians and religions.

The Muslims in Macedonia were never seen as Greek nationals, nor were they allowed to serve in the Greek army. During the period from 1919 to 1922 the Greek army and state committed a wide range of atrocities mostly upon the Muslim populations, which included murder, starvation and disease. Most of these atrocities were committed during the Balkan Wars. But, the period before the Balkan Wars (1897-1912) the Greek state was allied with the Ottoman in subduing non-Greek Christians (Macedonians, Vlahs, Albanians etc.).

The relationship between Macedonian Christians and Muslims in the village of Zelenich as well as the rest of Greek occupied Macedonia during this period, did not involve military conflict, nor did it foster religious fanaticism through ethnic nationalism. The bonds that had been fostered over years among people of different ethnic and religious affiliations were not completely destroyed. Cross-faith interactions continued especially in Zelenich. This was confirmed by numerous accounts of Christian villagers in Zelenich and Muslims in other areas controlled by Greece.

On one account, a Muslim stated: “We did not have hatred or differences …. None of us seemed to be bothered with religion, language, the church or the mosque of the other. My father was friends with the Macedonian Orthodox priest. Some times, he (Macedonian priest) visited our house and we went to his house. We went to their weddings and celebrations, and they came to ours. Our Christian friends protected us and we protected them.” This was very evident during the 1903 Ilinden Uprising as mentioned above.

The long coexistence of the Christians and Muslims helped create a new culture through the combination of aspects of culture and religion. The Muslims even celebrated the Christian Orthodox feasts of Saint George, St. Elijah and Saint Demetrius. Christians also participated in Islamic feasts, including the Ramadan Bayram.

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 had significant implications for the Muslim population in Greek-occupied Macedonia. The war resulted in a series of territorial changes and population movements that affected the ethnic and religious composition of the region. During the war, Greece sought to expand its territory and influence, and as a result of its military advances, Greek forces occupied parts of Macedonia that were previously under Ottoman control. This led to the displacement and migration of Muslim communities, including Turks, Albanians, and other ethnic groups, who predominantly practised Islam.

As Greek forces advanced and established control over these areas, they implemented policies aimed at Hellenization and assimilation. Muslims in the occupied territories, including Macedonia, faced pressures to assimilate into the Greek cultural and religious framework. Greek authorities enforced policies that sought to suppress Islamic practices, promote Greek language and culture, and encourage conversion to Christianity.

Muslim institutions, such as mosques and religious schools, were often targeted and, in some cases, converted into churches or repurposed for other uses. Muslim religious and cultural practices were restricted, and the use of the Turkish language was discouraged. This cultural assimilation policy was part of a broader nation-building project undertaken by the Greek state.

The war and its aftermath also led to population exchanges and migrations between Greece and Turkey. As a result of the conflict, a population exchange agreement was signed between Greece and Turkey in 1923, known as the Treaty of Lausanne. This agreement aimed to address the issue of minorities in both countries and resulted in the forced migration and exchange of populations, primarily between Muslims in Greece and Orthodox Christians in Turkey.

As a consequence, many Muslims, including those in Greek-occupied Macedonia, were compelled to leave their homes and properties behind and relocate to Turkey. This population exchange had a profound impact on the demographic composition of the region, with Muslim communities significantly reduced in size or entirely displaced from Greek-occupied territories.

Overall, the Greco-Turkish War and its aftermath had a trans-formative effect on the Muslim population in Greek-occupied Macedonia. Many Muslims faced displacement, assimilation pressures, and migration, resulting in significant changes to the region’s ethnic and religious landscape.

Conscription of Macedonians in the Greek Army

The first two decades of the twentieth century demonstrated a distinctive form of political realism towards the non-Greek speaking and non-Greek Orthodox populations of the New Lands. The attempt to incorporate these populations into the Greek state was based on brutal assimilation policies at the expense of minority populations, including those of different ethnic, linguistic, and religious backgrounds.

One such group affected by these policies was the ethnic Macedonian population. The goal was to assimilate them into the newly formed Greek state by promoting Greek language, culture, and Orthodox Christianity, while suppressing or marginalizing their own cultural and religious practices. These policies included restrictions on language use, forced conversions, and discriminatory practices against non-Greek communities.

The war in Anatolia had a two-fold affect, the first being the acquisition of new lands in Asia Minor and the second, assimilating conquered non-Greeks (Macedonians, Albanians, Vlahs) through the use of conscription and war. They had to persuade their citizens, the Great Powers and the people living in the newly occupied territories over which they had jurisdiction of their right to incorporate them into their nation-states.

English historian Arnold Joseph Toynbee travelled throughout the Morea and Macedonia at the end of WWI and got some notion of the general state of feeling in the country. Macedonia had only been occupied by the Kingdom of Greece after the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and, like most of the newly occupied territories, for the Macedonians conscripts fighting overseas, Anatolia was as foreign to them as the country of Greece they were fighting for. Toynbee made his journeys to Anatolia in 1921 as special correspondent for the Manchester Guardian.

During this war, there were instances of conscription of Macedonians by both the Greek and Turkish sides. Macedonia, located in the northern part of Greece and the southern Balkans, was a region with a mixed population of various ethnic and linguistic groups, including Greeks, Bulgarians, Albanians, and Macedonians. The issue of Macedonian identity and affiliation was complex and often contested during this period.

On the Greek side, as Greece sought to expand its influence and territorial control, there were efforts to mobilize and recruit Macedonians into the Greek armed forces. The Greek government encouraged Macedonians to enlist voluntarily or through conscription to support the Greek war effort against the Turkish forces. However, the extent of Macedonian involvement in the Greek military during this war is not extensively documented, and specific numbers regarding conscription are not readily available.

Similarly, the Turkish side also attempted to mobilize various ethnic groups, including Macedonians, to defend against Greek advances into Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). The Turkish authorities aimed to consolidate support among local populations, and individuals from different ethnic backgrounds, including Macedonians, were called upon to join the Turkish forces. Again, specific details regarding Macedonian conscription or the scale of their involvement in the Turkish military are not widely documented.

It’s important to note that the Greek-Turkish War was a complex conflict with various political, ethnic, and territorial dimensions. The experiences of Macedonians during this period varied depending on their specific circumstances, loyalties, and the regions they inhabited. Many Macedonians living in Greece were conscripted into the Greek army to fight in the war. It is estimated that thousands of Macedonian men from Greek Macedonia served in the Greek army during this conflict, but the exact number is difficult to determine.

However, they failed to understand that, at the local level, the decision to adopt a nationality during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century was a political choice very often irrelevant to the socio-cultural identity and linguistic practices of those who took this decision. This was an attempt at social engineering in which certain customs and morale (that is socio-cultural, linguistic, and historical characteristics) were to be used for creating a different national awareness.

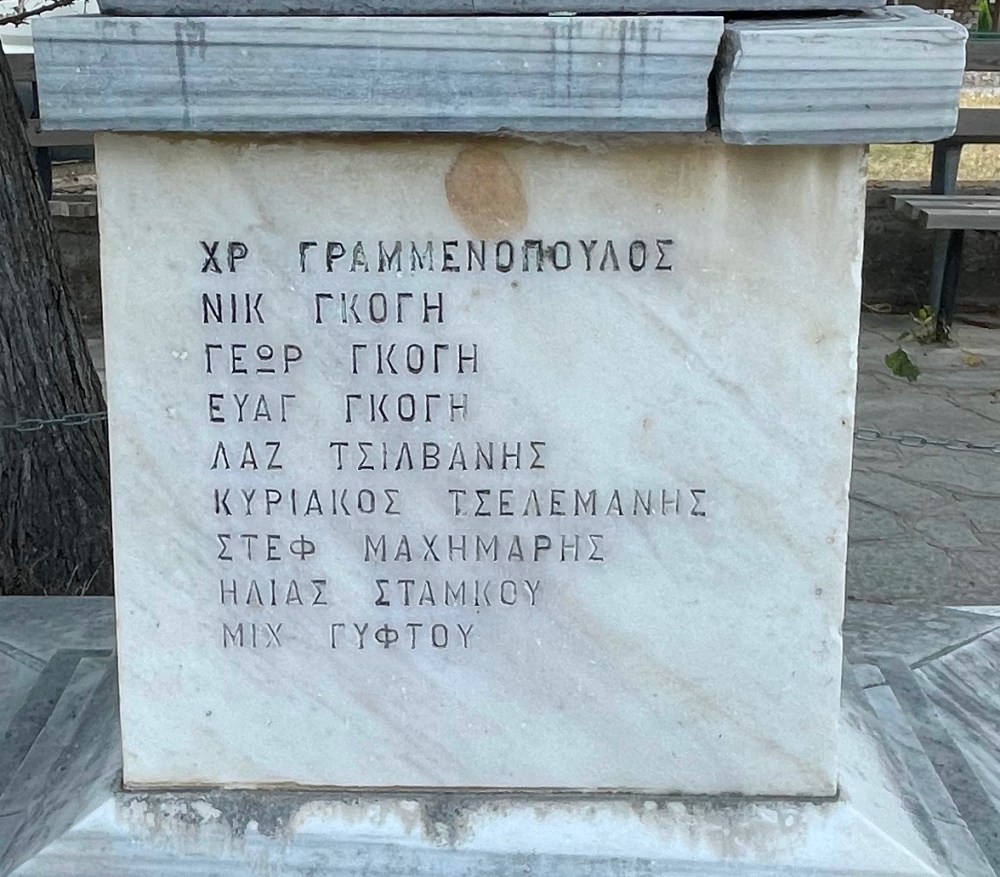

Zelnicheni Killed in the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922

Impact of War on Macedonia and Macedonians

The Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 and the subsequent Greek occupation of parts of Macedonia had a significant impact on the Macedonians living in those territories. The war and its aftermath brought about political, cultural, and demographic changes that affected the Macedonian population.

- Political Changes: The Greek occupation of Macedonia during and after the war led to the incorporation of these territories into the Greek state. As part of Greece’s nation-building efforts, the authorities sought to assimilate the Macedonians into the Greek national identity. This involved imposing Greek language, culture, and institutions on the local population, including the Macedonians.

- Cultural Assimilation: Greek authorities implemented policies aimed at promoting Greek language and culture while suppressing Macedonian cultural expression. Macedonian language and customs were actively discouraged, and the use of the Greek language was enforced in schools, administration, and public life. This assimilation policy sought to diminish the distinct Macedonian identity and integrate the population into the Greek national fabric.

- Repression and Discrimination: Macedonians who resisted assimilation and advocated for their distinct identity faced repression and discrimination. The Greek state viewed Macedonian national aspirations as a threat to its territorial integrity and sought to suppress any expression of Macedonian nationalism. Macedonian cultural and political organizations were banned, and individuals advocating for Macedonian identity were often persecuted.

- Displacement and Migration: The war and the subsequent population exchange between Greece and Turkey under the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923 also affected the Macedonians. While the population exchange primarily targeted Muslims in Greece and Orthodox Christians in Turkey, some Macedonians who identified as Greeks or were considered as such by Greek authorities were forcibly relocated to Greece. At the same time, some Macedonians who were seen as not conforming to the Greek identity or were suspected of sympathizing with the Turkish cause were also compelled to leave their homes.

- Demographic Changes: The Greek occupation and the subsequent population exchanges resulted in significant demographic shifts in the region. The Macedonian population in the Greek-occupied territories decreased as some were forced to migrate or assimilated into the Greek identity. This had long-lasting effects on the Macedonian presence in these areas.

It’s important to note that the experiences of Macedonians during this period were diverse and varied depending on their specific circumstances, affiliations, and responses to Greek assimilation policies. The impact of the Greco-Turkish War and the Greek occupation on the Macedonians was complex and influenced by political, cultural, and demographic factors.

Soldier Diaries of the War

There are several soldier diaries and memoirs available that provide firsthand accounts of the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922. These personal narratives offer valuable insights into the experiences, perspectives, and challenges faced by soldiers during the conflict. Some notable soldier diaries include:

- “Diary of the Greek Campaign” by Spyridon Giannaris: This diary provides a detailed account of the author’s experiences as a Greek soldier during the Greco-Turkish War. It offers insights into the military operations, battles, and the daily life of a soldier.

- “I Fought for the Fatherland” by Demetrius Ypsilantis: This memoir provides a firsthand account of a Greek soldier’s experiences during the Greco-Turkish War. It covers various aspects of the conflict, including battles, strategy, and the political climate of the time.

- “Memoirs of a Turk: The Diary of a Young Ottoman in the Great War” by Taha Toros: While not specifically focused on the Greco-Turkish War, this diary provides an Ottoman soldier’s perspective on World War I, which had a significant impact on the subsequent conflict with Greece.

- “To Smyrna in Flames: The First Turkish-Greek War 1919-1922” by Marjorie Housepian Dobkin: Although not a soldier diary per se, this book compiles eyewitness accounts and memoirs from both Greek and Turkish participants, including soldiers, civilians, and foreign observers, providing a broader perspective on the war.

These diaries and memoirs can offer valuable firsthand information about the war, shedding light on the personal experiences, emotions, and challenges faced by soldiers during the Greco-Turkish conflict. They provide a more intimate and human perspective on the events and can deepen our understanding of the war’s impact on individuals involved.

Conclusion

The Greek Asia Minor Campaign, and disaster is one of the most tragic moments in the modern history of Greece, Turkey and the over 2 million people who were forcibly displaced, not to mention the thousands of soldiers who died or were injured. Starting in a climate of artificial enthusiasm from the dominant political forces of the place, it ended in an unprecedented tragedy, with the Greek state and the hard-working Christians living in Asia Minor mourning thousands of dead and wounded. As a consequence, about 1.5 million Christian Turks were forced to leave Ottoman Anatolia for Greece, and over 400,000 Muslim Greeks were forced to leave Greece, all victims of the Asia Minor war. The material destruction and damage from the war in Anatolia and the lost immovable properties that were abandoned or destroyed in both countries amounted to tens of millions of dollars.

Mainstream Greek historiography, particularly in the aftermath of the Catastrophe (referring to the defeat and expulsion of Greeks from Asia Minor in the early 1920s), played a role in fabricating narratives that supported a hegemonic nationalist discourse, which was closely tied to the nation-building process in both Asia Minor and the Balkans.

After the Catastrophe, Greece experienced a massive influx of refugees from Asia Minor, which led to a sense of national trauma and the need to create a cohesive national identity. In this context, mainstream Greek historiography played a crucial role in shaping the historical narrative to foster a strong sense of national unity and pride.

To achieve this, certain elements of the historical record were selectively emphasized or manipulated while others were downplayed or ignored. This process involved glorifying the historical achievements of Greeks and highlighting their contributions to civilization while portraying other communities in the region in a negative or inferior light.

The fabrication of historical narratives was aimed at legitimizing territorial claims, especially regarding contested regions like Macedonia and parts of Asia Minor. The goal was to reinforce the idea that these regions were inherently Greek and that the Greek presence there was both ancient and continuous.

This hegemonic nationalist discourse also sought to portray Greece as a victim of external forces and unjust aggression. By emphasizing Greece’s suffering during the Catastrophe and presenting the events as part of a broader conspiracy (today called conspiracy culture) against the Greek nation, the narrative aimed to unite the population and create a common enemy.

However, it’s important to note that historiography is a complex field, and not all Greek historians followed the mainstream nationalist discourse. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in more critical and balanced historical research, seeking to examine the events of the Catastrophe and the broader nation-building process from a more nuanced perspective, considering the experiences and narratives of all communities involved in the region’s history.

One of these critical and balanced historical research narratives comes from Greek researcher and journalist Tasos Kostopoulos, in his book “1912-1922 War and Ethnic Cleansing.” He reveals the murders and barbarism of the Greeks during the occupation in Anatolia with witness statements and documents. Here are some striking passages from the book between 1919-1922:

- ‘’Greek soldiers and some armed local Christians attempted violence, murder, rape and looting for two days, citing several shots fired at the port of Izmir during the arrival of the Greek soldiers. 200 people were killed. 2500 people, including all the students and teachers of a class of a school, were arrested and tortured. The Greek soldiers attacked all the Muslim villages, as if a circle had been drawn up to a few kilometers beyond Izmir. The Allied research team blamed the Greek army for all the bloodshed in Izmir.’’

- ‘’(Greek doctor tells) In the village near Uşak, Turkish women, children and elderly people were closed to the mosque. Some of our soldiers noticed the situation. Instead of breaking the door of the mosque and raping the women, as all the dirty men would do, they burned the grass they collected and threw it through the window of the mosque. People ran out of the smoke, and then our rascals started shooting at women and children as if they were shooting drills …’’

- ‘’(Kopruhisar, 1920: Greek officer Dimitriu tells) I entered the house, I passed over the body of a dead old Turkish man. Noises coming from inside. About 10 Greek soldiers lifted the skirt of a Turkish girl, was forced to dance. They said to me, “Come and taste the appetizer.” I said ‘Shame’’ in Turkish. The Turkish girl rushed to my feet and said, “Save me.” I begged the soldiers, I said don’t do it. Somebody pulled out his bayonet and headed towards me. I had to escape. I couldn’t forget the woman’s screams. In the morning, about a thousand houses in Köprühisar were in flames.’’

- (A Greek soldier tells): Prince Andreas ordered us to burn everything.

- (August 30, 1921: A photographer from the Greek army tells): We burn everything we leave. It was a terrifying sight.

- (July 9, 1921: Greek officer tells): We entered Arıveren village. The girls were raped in front of their parents. The soldiers slept on the silk quilts they had ransacked that night.

- (Major Panagakos recounts): In Uşak, the Turks hid their families in cemeteries at night. I saved a young girl whom two Greek soldiers tried to rape. Her mother started running and kissing my hands. Shortly ahead, her other two daughters lay lifeless on the floor.

- Stelyo Berberakis said that ‘’Remaining thing after the reading of the book: The Greek army suffered because of the defeat in Anatolia, which was described as the “Asia Minor Catastrophe” in the country. And the fact that he had to take about 2 million Anatolian Greeks on his way back (with embarrassment) was not due to the “Turkish barbarism” as Greek nationalists suggest, but because of Greece’s attempt to expand its borders called “Megali Idea.”

In his book “War and Ethnic Cleaning of 1912-1922′’, Tasos Kostopoulos revealed the murders made by Greek soldiers in Anatolia. The writer said about the book:

‘’But I have to say this. I wrote this book with a focus only on the violence of the Greek army and the mistakes of politicians. I tried to show that it was no different from the violence that we were facing. That is, whether it be Turkish, Bulgarian or Serbian. I wanted to remind you that official history should be impartial. I believe that sooner or later nations should accept their own mistakes, the murders they commit. People who will read my book in Turkey, if they will only say”Here the Greek barbarism” or If it’s going to evoke feelings of hatred towards Greece, it’s better not to ever publish. As a researcher, my aim is to spread the fact that each Balkan country faces its own history, mistakes, murders. I believe that as these self-criticisms spread, the feelings of hatred among nations will diminish and the trumps of the extreme nationalists will disappear one by one.”

Sources:

Agelopoulos, G. (2010). Contested Territories and the Quest for Ethnology: People and Places in İzmir 1919–22. In Spatial Conceptions of the Nation: Modernizing Geographies in Greece and Turke (p. 46). Tauris Academic Studies. https://mahabbet.uom.gr/Projects/Documents/NationBuilding/Quest%20for%20Ethnology%20G.%20Agelopoulos%20(CORRECT).pdf

Alexikoua. (2014, January 17). Map of the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) [Map]. Wikimedia. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/Greco_Turkish_War_1919-1922.svg

Daleziou, M. (2010). “Neither heroes nor cowards” Narratives of Greek soldiers’ experiences during the Asia Minor War (1919-1922. University of the Aegean – Dpt. of Social Anthropology & History, 6. https://www.academia.edu/38179392/_Neither_heroes_nor_cowards_Narratives_of_Greek_soldiers_experiences_during_the_Asia_Minor_War_1919_1922_?auto=download

ERT. (2022, October 12). Αφιέρωμα από το Αρχείο της ΕΡΤ: Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή Αύγουστος 1922 [Tribute from the ERT Archive: Asia Minor Catastrophe August 1922]. http://www.ert.gr. https://www.ert.gr/ert-arxeio/mikrasiatiki-katastrofi-aygoystos-1922/

Karathanasis, A. E. (2021). Αξέχαστος Πόνος: 42 αφηγήσεις από το μικρασιατικό έπος. Kyriakidis Brothers.

Katsikas, S. (2020). Chapter 8: Life in the rear: The Muslims of Greece during the Anatolian Wae 1919-1922. In Salvation and catastrophe: The Greek-Turkish war, 1919–1922 (p. 44). Lexington Books.

Kinley, K. (2019, May). The Greco-Turkish war. Origins. https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/may-2019-greco-turkish-war-smyrna-sakarya-kemal-ottoman?language_content_entity=en

Κωστοπουλος, Τ. (2007). Πόλεμος και εθνοκάθαρση: η ξεχασμένη πλευρά μιας δεκαετούς εθνικής εξόρμησης (1912-1922) [War and Ethnic Cleansing: The Forgotten Side of a Ten-Year National Surge, 1912-1922] ΒΙΒΛΙΟΡΑΜΑ.

Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία – Δ’ | Greece paradise. (2023, January 6). Greece Paradise. [Asia Minor Campaign Pictures] https://greeceparadise.gr/9-mikrasiatiki-ekstratia-d/

Nur, E. (2020). [Review of the book “1912-1922 War and Ethnic Cleansing” Tasos Kostopoulos]. Quora. https://www.quora.com/Why-did-the-Greek-army-massacre-civilian-turks-when-they-invaded-Izmir-what-do-the-Greeks-and-Turks-think-about-the-massacres-carried-out-by-the-Greek-army-in-Izmir#nifqQ

Palaio-biblio. (2007). [Book Cover]. https://www.palaio-biblio.gr. https://www.palaio-biblio.gr/katastima/istoria/polemoskaieunokauarshkvstopoylosbibliorama2007-detail.html

Rizospastis.gr | Synchroni Epochi. (2008, May 25). Rizospastis.gr – Η Μικρασιατική Εκστρατεία και Καταστροφή. ΡΙΖΟΣΠΑΣΤΗΣ. https://www.rizospastis.gr/story.do?id=4557180

Toynbee, A. (1922). The western question in Greece and Turkey: A study in the contact of civilizations. CONSTABLE AND COMPANY LTD. https://louisville.edu/a-s/history/turks/WesternQuestion.pdf

Travlos, K. (2020). Salvation and catastrophe: The Greek-Turkish war, 1919–1922. Lexington Books. Unforgettable Pain: 42 Tales from the Asia Minor Epic. (n.d.).

Tsimouris, G. (2011). From Christian Romioi to hellenes: Some reflections on nationalism and the transformation of Greek identity in Asia Minor. Bulletin of the Centre for Asia Minor Studies, 17, 277. https://doi.org/10.12681/deltiokms.28

Van Buschoten, R., Dalkavoukis, V., & Kallimopoulou, E. (2020). Προφορική ιστορία και αντι-αρχεία Φωνές, εικόνες και τόποι [Oral history and anti-archives Voices, images and places]. Τμήμα Επικοινωνίας, Μέσων και Πολιτισμού – Αρχική. https://cmc.panteion.gr/images/Publications/Gazi_oral_history.pdf