The narrative expressed in this section will focus on the effect upon the people of Sklithro-Zelenich, the refugees and Greek (newly acquired) Macedonia. The Greek-Turkish population exchange of 1923 was complex and contradictory in ways that the events were experienced by individuals and the ambiguity in their depiction in Greek or Turkish national history, which mirror one another. While the Asia Minor “disaster” is mourned in Greece, it is the “liberation” of Izmir that is commemorated in Turkey.

As the Greek army was repelled from inner Anatolia to the shores of the Aegean, Christian subjects of the Ottoman Empire started fleeing to mainland Greece for fear of being massacred by the Turkish nationalists, a situation exacerbated by attempts by the Greek army to conscript them into fighting.

Religion Into Race

Religion had become racial identity as populations were uprooted, neighbourhoods destroyed, trade networks eradicated, and human families dislocated. Religion as race was used as the definition to cull Christians and Muslims as the sole marker essential for nation-building, this objective was transparent with which both the Greek invasion and the Turkish response had been based.

The convention defined the two ‘races’ to be exchanged according to religion: Orthodox Christians would be sent to Greece, and Muslims would be sent to Turkey. Muslim-speaking Greeks whose ancestors had resided, procreated, traded, and worshipped within the new borders of Greece were deemed to be Turks; hundreds of thousands of such ‘Turks’ were relocated to the just-created Republic of Turkey, where many could not even speak the language. At the same time, one and a half million Orthodox Christians were forcibly relocated to Greece.

As from the first of May, 1923, there shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Muslim religion established in Greek territory. These persons shall not return to live in Turkey or Greece respectively without the authorization of the Turkish Government or of the Greek Government respectively.

“Races” had been defined by faith tradition: Muslims were henceforth “Turks” and Orthodox Christians became “Greeks.” Greek-speaking Muslims who worshipped within the new borders of Greece were deemed to be Turks; half a million “Turks” were relocated to the just-created Republic of Turkey, where they could not even speak the language. At the same time, some 1.3 million Turkish-speaking (Greek) Orthodox Christians — whose ancestors’ lives within the area now defined as Turkey were now forcibly relocated to Greece. Religion had become racial identity as the exchange decision was a decision taken in line with the wishes of both Turkey and Greece in making their societies homogeneous in terms of religion.

As a result of the Exchange Agreement of Exchanged Settlements in Turkey, approximately 1,200,000 Orthodox Christians residing in all Anatolia and Eastern Thrace, except for Orthodox Christians residing in Istanbul, Gökçeada and Bozcaada, were sent to Greece, and 456,720 Muslims living in Greek territory except Western Thrace were sent to Turkey. The use of Muslim and Orthodox expressions instead of Turkish and Greek expressions in the agreement brought with it the problems that are still felt today.

The Treaty

After the signing of the Lausanne Convention, on January 30 of 1923 and the exchange of refugees was ratified on December 17, 1923, the departure of the Muslim populations from Macedonia began. The peoples to be exchanged and the persons not covered by the exchange and the compulsory character of the exchange were specified in the first two articles of the contract.

Article 1.

Compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of Greek Orthodox religion settled in Turkish territory and Greek nationals of Muslim religion settled in Greek territory will be undertaken, starting from 1 May 1923. None of these people will be able to return to Turkey without the permission of the Turkish Government or to return to Greece without the permission of the Greek Government and settle there.

Article 2.

Exchange envisaged in Article 1:

a) Greeks residing in Istanbul (Greek Orthodox Christian people of Istanbul);

b) It will not include Muslims residing in Western Thrace (Muslim population of Western Thrace).

All Greeks who settled (établis) before 30 October 1918 within the Istanbul Şehremaneti circles, as limited by the 1912 Law, shall be deemed to be Greeks residing in Istanbul. All Muslims who settled in the region east of the border line set by the 1913 Bucharest Treaty will be considered as Muslims residing in Western Thrace.

According to Sefer Guvenc, a researcher on the population exchange, before the official transfer nearly one million Christians had already left Anatolia while 200,000 Muslims had abandoned Greece. “The pressure on Muslims in Greece erupted in violence and most of the Turks were expelled from their homes before there was an exchange agreement. Nearly 300 thousand people were torn from their homes, slumped on the beaches, and lived for months, even more than a year, on the piers on shore, in very difficult conditions, in makeshift shelters, tents, without medicine, starving, naked, dying, getting sick.” This was evident for both Muslims and Christians who were being used as pawns on both sides of the conflict.

One challenge encountered by the Greek authorities was according to Greek sources, the attempt to Slavicize many Turkic Muslim people of the Macedonian region with the obvious aim of excluding them from the exchange and the conservation of their properties. Many of the Muslims in Macedonia, spoke Macedonian who even to this day their ancestors carry on with Macedonian cultural traditions in the regions of Turkey where they settled.

The forced migration of the 1923 Greek-Turkish Population Exchange changed the lives of hundreds of thousands of people. On the one hand, the refugees tried to adapt to their new homeland, on the other hand, they tried to keep their identity and culture created by the land they were born in. They soon found that this was going to be more difficult than they were promised by the authorities who were encouraging people to leave their homelands.

However, since the agreement included those who had migrated since the First Balkan War (1912-13), it is estimated that 3 million people in total were affected by the exchange. The exchange brought about a serious change in the demographic structure of both countries: At that time, Turkey was a country of 11 million people and Greece a country of 3.5 million people.

Demograpic Engineering = Ethnic Cleansing

The displaced population had a significant impact on the demographics of both countries, what today is called “Demographic Engineering” or “Ethnic Cleansing.” Although the agreement was signed on January 30, 1923, the migration of the exchanged did not start immediately. According to the agreement, both sides had to carry their own immigrants.

According to one witness, “Turkey was only able to prepare to bring the Muslim refugees in the later part of 1923. Most of the ships were dry cargo ships, and in the harsh winter conditions the refugees had to be brought on these ships in the open, in the rain, under the snow and in the cold.”

Reaching their destination after a difficult journey did not mean the end of the problems for the refugees. One of the most important problems was housing. In Turkey some of the houses left by the Orthodox population immigrating to Greece were burnt down while the Greek army was withdrawing. In Greece, Muslims still occupied their homes sold them to those who had funds to pay, others had to wait for housing to be distributed by the state.

| il (Province) | Göçmen (Immgrants) | il (Province) | Göçmen (Immgrants) |

| Adana | 7,628 | Izmir | 30,095 |

| Afyon | 1,045 | Istanbul | 35,487 |

| Aksaray | 3.286 | Kars | 2,512 |

| Amasya | 3,673 | Kastamonu | 769 |

| Ankara | 1,779 | Kayseri | 6,703 |

| Antalya | 4,702 | Kirklareli | 27,254 |

| Artvin | 46 | Kırşehir | 193 |

| Aydin | 6,484 | Kocaeli | 20,740 |

| Balikesir | 37,088 | Konya | 5,020 |

| Bayazit | 2,856 | Kütahya | 1,855 |

| Bilecik | 4,126 | Malatya | 76 |

| Bitlis | 2,329 | Manisa | 13,829 |

| Bolu | 194 | Mardin | 0 |

| Burdur | 432 | Maraş | 1,132 |

| Bursa | 34,148 | Mersin | 3,330 |

| Cebelibereket | 2,718 | Mügla | 4,045 |

| Çanakkale | 10,856 | Niğde | 15,671 |

| Çankiri | 0 | Ordu | 1,123 |

| Çorum | 1,575 | Rize | 0 |

| Denizli | 2,459 | Samsun | 22,479 |

| Diyarbekir | 298 | Siirt | 0 |

| Edirne | 49,336 | Sinop | 1,189 |

| Elaziz | 1,452 | Sivas | 4,892 |

| Erzinkan | 97 | Ş. Karahisar | 5,779 |

| Erzurum | 1,095 | Tekirdağ | 30,243 |

| Eskişehir | 2,441 | Trabzon | 404 |

| Giresun | 596 | Tokat | 8,209 |

| Gümüşhanı | 596 | Urfa | 1 |

| Gaziantep | 811 | Van | 275 |

| Hakkāri | 145 | Yozgat | 32 |

| Içel | 1,000 | Zonguldak | 1,241 |

| Isparta | 1,096 | Toplam (Total) | 431,065 |

The peasant population in Turkey and the urban population in Greece increased. While most of the Muslims who came from Greece were poor, most of the Christians who went from Turkey were rich. Just as they left their real estate behind, the Christians also left their goods and money to their trusted neighbours or buried them, as they found it impossible or risky to take them with them. Most of them thought that the exchange was temporary and that they would return since they left before the treaty was finalized.

The exchange was especially beneficial for Greece, which needed a trained population; The business-like Orthodox people of Anatolia contributed to the economic strengthening of Greece. While Greece made great progress in fields such as tobacco growing, viticulture, silk farming and carpet weaving, thanks to the Christian farmers, Turkey on the other hand, took longer to have similar economic growth.

The refugees who were exchange were considered strange by the local people on both sides, even ostracized. Not all the Muslim refugees who went to Turkey could speak Turkish. The Christians who went to Greece also experienced adaptation problems as most of them did not speak Greek.

Sklithro- Zelenich 1924

Zelenich, a village of over 2,000 Christians and 1,100 Ottoman (Muslim) residents: had 3 churches, 2 mosques; there were 3 inns, a boys’ school, plenty of water, and due to its location, there was plenty of food, especially wheat and barley; 310 households of Christian Macedonian Slavs and 170 Muslim Turks [1920]. In 1924, Muslim people had to migrate to Turkey. The Greek administration settled Christian refugees from Asia Minor, Thrace and the Caucasus into their homes. At the same time some 15 properties of Macedonian residents who emigrated to Bulgaria were liquidated. By 1926, 87 refugee families (379 Christian refugees) were resettled.

In the exchange, 170 Muslim families (1,100 people) left, and 89 refugee families arrived: 23 from Thrace, 53 from Asia Minor, 10 from the Caucasus and 3 from other places. According to the 1932 Greek statistics, in Sklithro-Zelenich, there were 353 foreign language-speaking families, 326 of whom were of declared Slavic faith.

IMMIGRANT REGISTRATION DOCUMENT FOR EXCHANGES

A document given to those who migrated during the population exchange the “Immigrant Registration Document.” As we know, liquidation requests were documents that the delegations formed after the exchange agreement went from village to village accompanied by the village headman and members, to prove their property in the places where they lived. The following are the names of those Muslim villagers from Zelenić who sold their properties to the refugee Christians who had to leave Turkey as part of the exchange.

LIST OF MUSLIM REFUGEES NAMES FROM FLORİNA ZELENICH (Sklithro)

| # | Name of Individual | Father’s Name | Date of Request | Details | Reference Number |

| 1 | Zekeriya, son of Nasuh | Nasuh | 01.03.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province | 191-259-15 |

| 2 | Kasım, son of Ali | Ali | 30.05.1925 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province, resettled in Bursa province | 182-206-3 |

| 3 | Arif, son of Hayrettin | Hayrettin | 05.02.1925 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province | 182-205-1 |

| 4 | Hasan, son of Hüseyin | Hüseyin | 22.02.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province, resettled | 181-200-17 |

| 5 | Şakir, son of Süleyman | Süleyman | 10.06.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province, resettled | 181-200-19 |

| 6 | Abdül, son of Mehmet | Mehmet | 00.00.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province | 176-169-1 |

| 7 | Yaşar, son of Bekir | Bekir | 09.06.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province | 176-169-2 |

| 8 | Besim, son of Davut | Davut | 05.03.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province, profession: farmer | 176-169-3 |

| 9 | Abdul, son of Mehmet | Mehmet | 25.05.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province | 176-168-16 |

| 10 | Zekeriya, son of Nasuh | Nasuh | 01.03.1924 | Liquidation request from Zeleniç village in the Florina district of the Manastır province | 191-259-15 |

The list below indicates the number of people and year they were forced to leave Zelenich-Sklithro:

- 170 Families 1100 people (Muslims) 1923

- 10 families 28 people Kafkasiou 1926

- 23 families, 93 people Thrakiotes 1926

- Oral history states that the last of the Muslims left in 1930.

The later three groups of people had settled in the village during the Balkan Wars and WWI. The first group of people were families of the original settlers from the early 1400s to the 1800s.

The outgoing population added a great wealth to the Turkish side. It was noticed that the education level of the population coming to Turkey was higher than the local population and, emphasized that the exchanged people were also a group that was more affected by European enlightenment. After their arrival to Turkey, these people became involved in very important places of the economy, education and art and made important contributions to Turkish culture and the economy. The Turkish society was influenced by immigrants from the Caucasus, Arab states, Africa and the Balkans, and that mass gathered in Anatolia. One of the strongest, most dynamic, coming from the Balkans especially Macedonia.

The settlement of the Muslim Greeks who went to Turkey seemingly did not present any considerable difficulties. They left Greece in an orderly manner and were able to carry along their movable property. The Muslim emigrants from Greece were installed in villages and properties that were left by Christian refugees. Land was abundant and according to Turkish authorities, every settler was granted sufficient space to secure their livelihood.

Where did the Macedonian Muslims from Zelenich-Sklithro Settle in Anatolia?

Those who left Sklithro-Zelenich, settled in Kaszmi-Dikili district, Bayındır/Izmir, İzmir-Dikili, İzmir-Bayındıra, Cumaovası, Bulgurca, Konya ,Sağancı, Ereğlide, and the other half went to Benimzmir-Bayindira.

One of the locations is Dikili on the Aegean coast of Turkey. One can see that the Muslims did not forget their birthplace Zelenich (Zelenícli on their headstones) and their place of business indicating “zeleniç’li” – From Zelenich. Their love for their ancestral homeland is very evident.

WHO WERE THESE BALKAN MUSLIMS?

Before 1360, large numbers of nomad shepherds, or Yörüks, from the district of Konya, in Asia Minor, had settled in Macedonia; their descendants were known as Konariotes. Further immigration from this region took place from time to time up to the middle of the 18th century. After the establishment of the feudal system in 1397, many of the Seljuk noble families came over from Asia Minor; their descendants may be recognized among the Beys or Muslim landowners in Kayılar (Ptolemaida). At the beginning of the 18th century, many Albania muslims benefited from the privileges granted to them by the Ottoman administration moved into Western Macedonia and intermixed with the descendants of the original Yörüks. Most of them wanted to be called Turks and as a result of intermarriages, they moved to Turkey instead of going to Albania.

According to Cemal Şenses a large part of the Muslims in Macedona were of Albanian descent. He states that they preferred Turkey rather than going to “miserable” Albania. He goes on to say that all the Albanians belonging to the Muzaka tribe in Kesriye (Kastoria) migrated to Florina, some most likely to Zelenich. Many of these people migrated to Monastir (Bitola) before the exchange. They spoke Abanian and had difficulty speaking Turkish after the exchange.

In the 1481 Ottoman census, there were two Muslim families included in the census. Eventually many more settled in what was then called Zelenich and of those who came to the village, they were thought to be “Sapahis” – cavalry men who were given free land upon retirement as soldiers. This is supported with anecdotal oral history from descendants of these Muslims who now live in Turkey. Occording to Özel Gündoğan (who lives in Dikili), his ancestors came from Zelenich and they were supposedly cavalry soldiers. The Muslim population of the Balkans was hardly homogeneous in terms of language, and even less so in Macedonia. The communities in Western Macedonia of Ostrovo (Arnissa), Voden (Edessa) and Yenice/Jenidže (Yannitsa) showed preference to a Slavic dialect commonly known as Macedonian.

Muslim Narratives:

- Mübadil – exchanged people (refugees)

- For instance, a Muslim mübadil, Refet Özkan, narrates his story: “We did not speak Turkish, our mother tongue was the Rum language. . . .

- Another mübadil, Murtaza Acar, similarly narrates how the “natives,” the locals in the recipient country, disapproved of the mübadil speaking Greek: “The locals complained that we spoke Greek.

- Other Muslim mübadil, Salih Tilki and Saliha Korucu, relate similar incidents after they came to Turkey, how people (the “natives”) would call them “creatures” and spread rumors that the exchanged people devour humans

- On the roof [of our house in Nevsehir] my mother used to dry apples and pears. . . . I would eat apples and pears. . . . Their taste was so different. . . .I don’t eat pears here [in Greece]. . . . The aromatic pear of Nevsehir does not exist here

- The homeland is valued and remembered through the taste of the fruits grown in its soil. The rupture of the exchange surfaces at yet another level in these nostalgic narratives depicting the attachment to the lost homeland and its soil. In other words, the mübadil renders his or her lack of compatibility legible through his or her longing for the taste of fruits in his homeland.

- İsmet Altaylı’s accounts how food tasted different in the departed lands, not only because of different ways of preparation but because of the way vegetables and fruits tasted. Visions of the departed land, the smell and taste of the water and agricultural products, but also music, songs from the lost land, are part of these nostalgic scenescapes that communicate a yearning for the lost homeland and a sensory return to this place

- Florina was quite a mosaic. Ullahs. Macedonians, Albanians, Torbeşs, Jewish community there were Serbs and Pomaks and of course Turks. In general, the population of Albanians was more in rural areas (Nurhayat Filiz).

- “We didn’t leave the animals alone there! We left our childhood, our youth, our memories. Who knows how many generations we left our ancestors lying in those lands. We soon boarded the black train from Florina. First a long whistle whistled; Then it moved slowly. The road of our village remained behind the smoke it blew. We started to cry. We would never see it again and walk that road upwards. We came to Thessaloniki via Karaferye. The dock was packed with thousands of people. The environment was miserable and miserable. They made us wait in Tumba, which overlooks the bay, until it was our turn to board the ferry. They divided the people of the village into two ferries; the first one went to Izmir; we went to Mudanya.” (İsmet Altaylı)

- The exchange began in 1923 and families left the city of Florina and the Turkish departure ended in 1929. Many families fled to Albania because of the exchange. Plenty of them left though. At the exchange, there was sadness and wailing all over the city. Turks and Muslim Albanians were taken to Armenochori train station accompanied by gendarme. Children women everybody was crying. Slowly they left, and whenever a group left, sad cries could be heard from all over the neighborhood. Muslims and Christians living together in the same neighborhood said goodbye crying. They had a hard time asking the Turks to leave. Some Turkish families reacted and became Christians. But why did these families choose to remain Christians. This is still an unknown social cause (Cemal Şenses).

The immigrants who migrated from Kozana, Kayalar, Florina, Gerebene, Nasliç and Kesriye, which were connected to the Bitola province during the Ottoman rule, also call themselves Saloniki. There may be two reasons for this. First reason; All immigrants from these settlements were put on ships from the port of Thessaloniki. They were kept in tents set up in the port of Thessaloniki for weeks, some months, for their turn to be shipped. Thessaloniki is the place where they say “farewell” to their “homeland” for the last time, “the land of my birth”. The second and most important reason is with Atatürk. Atatürk was born in Saloniki and became their protective shield against exclusion and injustice in their new homeland.

Florina-born Mbadil Necati Cumalı writes the story of leaving Florina in her book “Macedonia 1900” as follows:

“I understood my father not by the years we were together, but by the time he lived, and by the time he reached his age. He always watched the news of the War of Salvation by reading Quran and praying. What did he expect from winning the war- he never said it openly. But Florina’s, Selani’s all those caste, Baghdadi married, Muslim Macedonian lands being separated from Ottomans, was not a long story, but a ten-year-old. Even though it was in the hands of Greeks, Florina was still considered as an Ottoman town. Exactly, he is one of the stubborn Rumelis who doesn’t know the truth except what he knows. He has never accepted defeat. She didn’t want to believe when the Treaty of Lausanne was signed and heard that we as West Thrace Turks would be replaced with West Anatolian Greeks. “There is no such thing as that! ” he was saying. When the news became certain, he said “I’m not leaving Florina”. We are on the road. My father didn’t open his mouth until Thessaloniki. He stopped looking at the Macedonian lands, mountains and stones from the window of the train. He had a high back seat made of oak. On the day we were going to sail in Thessaloniki, we made him sit on his seat in front of the stairs of the customs landing to the dock so that he would not get tired. He was so drenched in his seat again, waiting without saying a word. While we were about to go to Vapura, suddenly, in the back, grabbed the fingerprints of the dock ladder with both hands. He was ninety nine years old. She was still strong strong . I’m Fehim Sergeant, Mr. Salih, we couldn’t get their hands off of some kind of fingerprints. “My place is Florina. Can’t leave my dead alone! Can’t leave my land! You go, take me on the train, I’ll go back to Florina, I’ll die in Florina… ”The steam left and it will leave, he didn’t understand the promise. With difficulty, we finally ventilated three people off the floor and separated their hands from the bars. We separated, but his feet were paralyzed. Vapura boarded his seat, cut from hand to foot. He was on his right mind, he spoke with ease like before. We settled in Urla as immigrants. He lived in his bed for three years in Urla. She would often stare away from where she looked. Sometimes, when he couldn’t control himself, he said, “Oh, I wasn’t going to leave Florina. I was going to die in Florina!” As he said this, the light of the Macedonian skies would be reflected in his gaze, which was now starting to become shadowy, with the projections of the mountains with wide rumps and steep shoulders, like a breed horse, and his face would be illuminated as if he had been stripped of the clouds.” (Cumalı, 1976, p.33-34). Viran mountains written by late Necati Cumali and Macedonia where 1900 passed, this is the place. So its former name is Sarıgöl, the other name is GORIÇKA. Gorichka, Nevaska, Zelenic, in a triangle, so to put it. Another famous novel by Necati Cumalı is “Devastated Hills: Macedonia 1900” (Viran Dağlar: Makedonya 1900), where he relates the history of his own family which descended from a long line of Turkish Beys (Cuma Beyleri, “the Beys of Djuma”), with the turmoil in the Balkans providing the background. This novel has been adapted (not very faithfully) for the television by Michel Favart in 2001 as a multinational ARTE production under the title “Le dernier Seigneur des Balkans” (The last Lord of the Balkans).

The initial reception of the Christian refugees in Florina

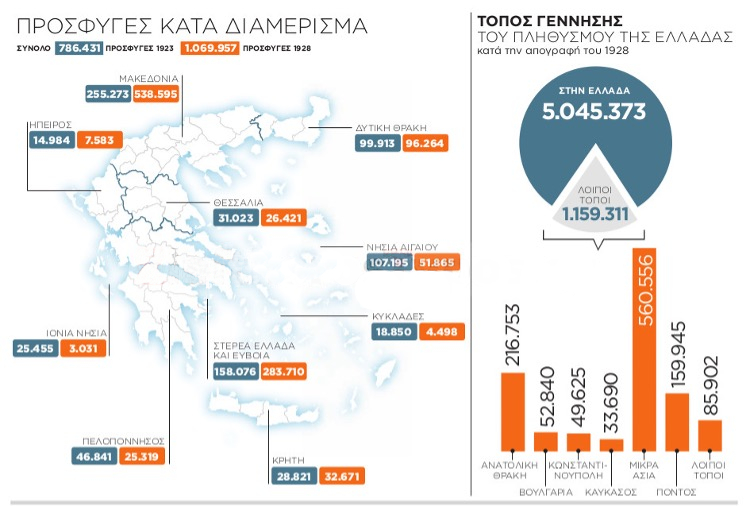

The initial reception of the refugees in Florina, was provided through the local press of Florina from the year 1922. The streams of refugees from Asia Minor, Eastern Thrace and the Caucasus arrived in Greece from 1919 to March 1923. According to the League of Nations, in many areas of their new settlement, 20% of refugees died of hardship in the first years, this corresponded to 1 birth to 3 deaths.

The area of Florina was not chosen by the refugees in their initial wanderings: the first evidence that exists and concerns the settlement of 3,746 refugees in the prefecture, goes back to 1922. The Pan-Hellenic census of the population in 1928 recorded throughout the province of Florina 12,463 refugees out of a total of 59,757 natives. The departure of 2,762 Muslim families with 14,320 persons recorded in the statistics of the “Province of Florina” of 1923, was completed from May to July 1924.

LAND DISTRIBUTION TO NATIVES & REFUGEES IN MIXED VILLAGES

The CHART below shows the mixed village settlements in which land was given because of the expulsion of Muslims from the Florina-Lerin region. One will notice that in various villages, land was only given to the refugees and in others, there are mixed proportions.

| Land Distribution | ||

| Villages | Locals (%) | Refugees (%) |

| Amohori | 0% | 100% |

| Anargyri | 0% | 100% |

| Kato Kleines | 0% | 100% |

| Laimos | 0% | 100% |

| Lefkonas | 0% | 100% |

| Petres | 0% | 100% |

| Skopia | 0% | 100% |

| Tripotamos | 0% | 100% |

| Niki | 100% | 0% |

| Armenohori | 67.72% | 32.28% |

| Meliti | 53.22% | 46.78% |

| Neochoraki | 62.89% | 37.11% |

| Ano Kleines | 2.7% | 97.3% |

| Kato Kalliniki | 48.61% | 51.39% |

| Mesonisi | 11.77% | 88.23% |

| Polyplatanos | 5.81% | 94.12% |

| Tropaiochus | 26.44% | 63.56% |

| Sklithro-Zelenich | 24.66% | 75.34% |

The final distribution of land in the mixed settlements took place from 1928 to 1974, quite a wide interval. The distribution was finalized earlier in Sklithro-Zelenich (1930), followed by Skopia, the Armenochori and Neochoraki in 1929, Tripotamos, Polyplatanos, Ammochori and Niki in 1933, Tropaiochus in 1935, Lefkonas in 1938, Kato Kalliniki in 1949, Laimos in 1954, Mesonisi in 1958, Meliti in 1961, Kolkhiki and Filotas in 1963, Ano and Kato Kleines in 1964 and Anargyri in 1974. Beneficiary refugees and natives were distributed parts of land that belonged to the total farms of each settlement.

Origins of Christian Refugee Locations for Zelenich-Sklithro

In 1926 we have 53 Asia Minor (Artaki, Sarikeio) families with 269 people, 23 Thracian families with 93 people, 10 Caucasian families with 28 people and 3 families of various other areas with 15 people. In total, there were 89 refugee families in the village with 405 individuals. In 1928 the families became 87 with 379 members. The agricultural lot given to 55 refugee families and 18 families of local residents; it was not shared equally. The final distribution of lots was made in 1928 with a final total of distributed areas of 3164 acres and 105 sq.m. in total 6752 acres and 735 sq.m. The inhabitants were engaged in the trade, crafts, were blacksmiths, farriers, butchers and small owners of hotels. Furthermore, the village had a police station, post office and a market that operated every Friday (Wednesdays and Fridays before 1912).

The exchanged population, in addition to their efforts to be integrated into their new homeland, sought to preserve their identities and cultures of origin, which had been shaped by their natal territories. But, by the 1950s, all of them completely lost their culture in customs, music, and dance. According to Angelo Rakopoulos writing about life in the village (ePeriskopio.blogspot.com – 2014) stated that there is nothing to remind them of their lost homeland.

Names of the Refugees who settled in Sklithro-Zelenich

| # | Names of Refugees | Origin Settlement | Region |

| 1 | Abartsis, Alexandros | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 2 | Argirakakis (Argirakis) Theodoros | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 3 | Asimakakis (Asimoglou), Apostolis | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 4 | Balas, Vasileios | Sarasli | Tekirdağ |

| 5 | Betis, Evangelos | Panormos | Balikesir |

| 6 | Burou, Maria | Kalivia | Tekirdağ |

| 7 | Dardagavis (Iopdavis) Konstantinos | Kalivia | Tekirdağ |

| 8 | Dermentzis (Milonas-Petros), Trifon | Kouri | Yalova |

| 9 | Diminas (Dimoglou), Ilias | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 10 | Fotiou (Arhontoula) Toutoula | Kalolimnos | Bursa |

| 11 | Frankoglou (Frangkou) Theodoros | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 12 | Georgiadis (Davagiloglou – Kabour), Ioannis | Aïnasi | Bursa |

| 13 | Georgiou, Stefanos | Seltzikioi | Tekirdağ |

| 14 | Giankoglou (Kafetzis-Sevdalis), Georgios | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 15 | Gonatis, Hristos | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 16 | Gousis (Mitsis) Athanasios | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 17 | Grigorakis, Georgios | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 18 | Hasanoglou, Souleiman | Nevie | Sakarya |

| 19 | Hatzi (Antoniou), Athanasios | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 20 | Hatzi (Theodosiou), Panagiotis | Prousa | Bursa |

| 21 | Hrisafidou, Despina | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 22 | Iordanoglou (Tsokalas) Vasileios) | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 23 | Isaakoglou, Saït | Akpounar | Kocaeli |

| 24 | Isakoglou, Atil | Nevie | Sakarya |

| 25 | Ismiloglou, Sefket | Esxine | Kocaeli |

| 26 | Kaisidis, Alexios | Sanamer | Stavropol’skiy kray |

| 27 | Kaisidis, Damianos | Magapatzik | Kars |

| 28 | Kaisidis, Elissaios | Magapatzik | Kars |

| 29 | Kaisidis, Iordavis | Sanamer | Stavropol’skiy kray |

| 30 | Kaisidis, Kiprianos | Magapatzik | Kars |

| 31 | Kaisidis, Kiriakos | Sanamer | Stavropol’skiy kray |

| 32 | Kaisidis, Kostantinos | Magapatzik | Kars |

| 33 | Kaisidis, Matthaios | Sanamer | Stavropol’skiy kray |

| 34 | Kaisidis, Pavlos | Sanamer | Stavropol’skiy kray |

| 35 | Kaisidis, Savvas | Sanamer | Stavropol’skiy kray |

| 36 | Kalaitzi, Anastasia | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 37 | Kanelos, Apisteidis | Kalolimnos | Bursa |

| 38 | Karaiskakis (Kapatzikos), Kpionas | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 38 | Karageorgakis, Iordanis | Petra | Kirklareli |

| 39 | Kapapantelakis, Anagnostis | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 41 | Karakosta (Psoma) Tasoula | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 42 | Karakostas, Konstantinos | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 43 | Karamanlis, Dimitrios | Karamisal | Kocaeli |

| 44 | Karamanlis, Ioannis | Karamisal | Sarikioi |

| 45 | Karofillis, Nokolaos | Haskioi | Tekirdağ |

| 46 | Katirtzis, Ioannis | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 47 | Katriliotis, Polivios | Kalolimnos | Bursa |

| 48 | Kepatidis, Theodoros | Optakioi | Kars |

| 49 | Kirezoglou, Anastasios | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 50 | Konstantinidis (Konstantinoglou), Hrisostomos | Tsinar | Yalova |

| 51 | Konstantinidou, Maria | Gkiordes | Manisa |

| 52 | Koploukoglou, Alhak | Esxine | Kocaeli |

| 53 | Koukepis, Sotirios | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 54 | Koukeri, Aspasia | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 55 | Kritis, Hristos | Kalolimnos | Bursa |

| 56 | Lazakis, Dimitrios | Seltzikioi | Tekirdağ |

| 57 | Lazaridou (Sakaloglou), Smaragdi | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 58 | Liogarakis, Dimitrios | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 59 | Manavis, Hristos | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 60 | Manavis, Panagiotis | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 61 | Manavis, Sotirios | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 62 | Manousakis, Athanasios | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 63 | Manousakis, Papasxos | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 64 | Memetoglou, Osman | Esxine | Kocaeli |

| 65 | Milonas, Kiriakos | Kouri | Yalova |

| 66 | Mos-hakis, Georgios | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 67 | Mousaoglou, Ismail | Pelik Kisla | Sakarya |

| 68 | Nikolaoglou (Hatzi Zafeiriou) Mihail | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 69 | Palios, Stefanos | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 70 | Pantemalis, Nikolaos | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 71 | Pantermali, Stavroula | Sukamnies | Balikesir |

| 72 | Pantermalis, Georgios | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 73 | Papadopoulos, Konstatinos | Prousa | Bursa |

| 74 | Papagiannis, Theodoros | Halkidon | Istanbul |

| 75 | Paraskeolos, Athanasios | Saxinkioï | Tekirdağ |

| 76 | Papastavros, Papadimitrios | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 77 | Pentikis, Panagiotis, | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 78 | Polemeroglou (Polimerou) Kirizis | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 79 | Psomas, Argipios | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 80 | Psomas, Ioannis | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 81 | Psomas, Spiros | Gkiordes | Manisi |

| 82 | Savva, Soultana | Zarakiva | Kirklareli |

| 83 | Servakis, Theodoros | Sentouki | Tekirdağ |

| 84 | Sideris, Konstantinos | Seltzikioi | Tekirdağ |

| 85 | Smirnios, Konstantinos | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 86 | Sosiaglou (Sosidis) Konstantinos | Kouri | Yalova |

| 87 | Theodosakis, Dimitris | Akintzali | Tekirdağ |

| 88 | Tsakiris, Hristos | Genitze | Çanakkale |

| 89 | Tsatalis, Georgios | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 90 | Tsesmetzis, Ioannis | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 91 | Tsiafoglou (Hrisafidis) Konstantinos | Sarikioi | Balikesir |

| 92 | Tsikas, Dimitrios | Tsinar | Yalova |

| 93 | Tsourtsouklis, Georgios | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 94 | Tsourtsouklis, Konstantinos | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 95 | Vangeloglou (Theodorakakis), Theodoros | Rebits | Tekirdağ |

| 96 | Volgaris, Ioannis | Artaki | Balikesir |

| 97 | Voulgarakis (Zerginis), Ioannis | Tsinar | Yalova |

| 98 | Voutsas, Ierotheos | Kalolimnos | Bursa |

Find your refugee relatives by your last name in the detailed list by using the following link below:

Over one hundred years have passed since this great historical event. It refers to approximately 250,000 refugees and the 2,000 settlements in Greece where those who took agricultural land settled. In the index volumes the name shown is that of the head of each family, with the “footnote” that there may be some who have a second and third surname and that those interested should look for it in another letter of the alphabet. The first document gives instructions on reading the catalogs (in Greek). Please note that the name list from X (Ξ ) to Papamichailou (Παπαμιχαήλου) is missing.

Christian Narratives:

- Chrsitian Orthodox mübadil (Refugees) from Asia Minor were met with similar reactions from the “natives.” Angela Katrini says: “We spoke Turkish. Turkish was our native language. They [the local people] would say ‘Turks arrived! These are Turks! The immigrants will take our fields! They should leave!’

- Another account from Kayserili Karabas reads: “Because we did not speak the Rum language they would say we were Turks, and they did not give us any woman to marry, nor would they take any woman from us [for the same purpose]

- Our grandparents came from Artaki in Asia Minor. My own grandparents were farriers in their homeland and continued this occupation when they came here. They were brought from Asia Minor to Thessaloniki by steamer and put there in some shacks, miserable and dirty. They stayed there for 1 year and then they were notified other friends that they can go to Florina to live better. So, they were divided and put them in Sklithro[Zelenich]. The village was rich and was the best.

Exchanged Christians

The exchange brought about not only a major demographic but also a social transformation in Greece, especially because the influx changed the demographics of Greece’s indigenous population in Macedonia. The refugees, in turn, were themselves transformed. Their sense of identity and belonging to the old world they left behind and the new one in which they settled changed dramatically over the next few decades.

The shaping of the identity of the Christians who fled the Ottoman Empire and settled in Greece was a consequence of the assimilation policies of the Greek government in creating a homogeneous (Christian) Greek Orthodox society. This policy was used to shape the identity of both the people in the newly acquired territories of Macedonia (after the Balkan Wars) and the refugees from Asia Minor.

These people did not consider themselves Greek. In reality, the refugees from Asian Minor held Ottoman citizenship and most did not even speak Greek. This was the case for many of those who settled in Sklithro-Zelenich. As for the indigenous Christians in Sklithro-Zelenich, their ethnicity was Macedonian not Greek. Both new and old, would be influenced by the assimilation policies to Hellenize the population in Macedonia.

The plight of many Christians on the Anatolian coast, especially those who came to Sklithro-Zelenich was only decided after the signing of the treaty of the exchange of populations. Many of them were Turkophone and enjoyed good relations with the local Muslim population. Stories passed on to later generations mentioned wealth and servants that were left behind.

The Greek invasion of Asia Minor destroyed the harmony that existed in many of the towns and villages that had cultured, cosmopolitan societies, all on the pretense of protecting Christians who were Greek Orthodox in religion and not ethnically Greek. There is ample evidence to support this view but, this is not the place for analysing the fallacies of the “Great Greek Idea” of the early twentieth century.

According to the Greek census of 1928, of the total number of 1,221,849 refugees 626,954 were from Asia Minor, 256,635 from Thrace, 182,169 from Pontos, 38,458 from Constantinople, 49,027 from Bulgaria, 47,091 from the Caucasus region, 11,453 from Russia, and 6,057 from Serbia. This variety made for a broad range of cultural and ethnic differences.

In rural areas, often entire villages, formerly occupied by Muslims who had left after the exchange, were inhabited by refugees, and the benefits of that arrangement for strengthening refugee Greek identity were obvious. But, in Sklithro-Zelenich there was a different outcome in the identity assimilation process. The tension between the newcomers and the indigenous Macedonians, who themselves were only incorporated into the Greek state ten years prior, posed many challenges.

Ironically, the refugees and the indigenous peoples were both being assimilated into the newly expanded Greek state. One commonality was that they could communicate by speaking Turkish. This was very evident in most rural area but, the refugees in the urban areas began to establish cultural and social organizations that catered to Greek interests. Those in Sklithro-Zelenich, began to mix with the indigenous population in the quest to just survive. Eventually, they would lose many of their customs and cultural traits, taking on the cultural traits of the indigenous Zelenich villagers and being assimilated into the new Greek identity. Elder members of this group used mainly the term Romioi (members of the Rum Millet) when they referred to their past. Mainstream Greek historiography, political discourse, and population representations designate the refugees as Asia Minor Hellenes. This abstract identification has been challenged as having been fabricated mainly after the war in the context of a hegemonic nationalist discourse and was associated with the nation building process in Asia Minor and Macedonia.

STORY OF EXCHANGE JOURNEY NARRATED BY STRATIS STRATAKIS FILOTA FLORINA – translated from Greek

I was born in 1917 in Bogaz Kioi in Eastern Thrace, which is about 15 kilometers from glorious Constantinople. Its name comes from the word Kioi which means village and the word Bogaz which means a narrow sea passage, because we were close to the Bosphorus. For others baggage means a place where there are air currents. The main occupations in Bogaz Kioi were agriculture and animal husbandry, and because we were in a place with rich vegetation, many residents were also engaged in logging.

Famous in the region were the charcoals of our village, which our fellow villagers sold in Constantinople and other large cities of Thrace. I was very young, and I don’t remember many things from our beautiful village. I only remember my parents, whose names were Dionysis and Sultanio, who every day went to work in our fields and in the evenings came back dead from fatigue. I also remember the beautiful church of our village which was dedicated to Saint Paraskevi (Friday).

On the day of her celebration, we held a big festival with dances and songs and the whole village celebrated, young and old. When the war between Greece and Turkey started, everyone in the village was worried. We did not think that one day we would be forced to leave our beautiful village where our relatives and villagers were buried. And when we learned that Greece lost the war, we understood that it was our turn. The Exchange of 1924 was very hard for us but, as we learned later, the other Greeks of Asia Minor had a much worse time and came to Greece naked. We loaded our things onto a cart and went to the port of Metre, put them on the ship and left devastated for Greece and the port of Thessaloniki.

There, for about fifteen days we lived in camps in Harman Kioi, where many refugees from all over Asia Minor and the Pontus lived. The villagers made us a committee which undertook to find a place where we would build our new homeland. Many villagers left us and settled in a village in Thessaloniki called Karasena. The rest of us followed the leaders and, after searching for several days, we came and settled in a Turkish village in the prefecture of Kozani, Tsanjilar. Pontians from the area of Sourmeni and Asia Minor from Avdimi had settled in the village.

In the beginning we had a lot of fuss and conflicts between us but later when things calmed down, we all worked hard to survive in our new home. We gave the village a new name, Filotas after the great general of Alexander the Great. In Filotas we engaged in agriculture because the fields were very fertile. Near us was the lake Vegoritida which slowly left towards Arnissa and left behind fertile fields. I was a handsome boy and a tomboy. All the girls wanted me as their man. I finally married Kyra Maria and had three children. I was also working hard as a porter carrying things from Filotas to other places. A few years ago, God helped me, and I went to my village Bogaz Kioi where the Turks welcomed us with great joy and even honored me with a commemorative plaque”. Lalistatos, the lovable grandfather of Stratis, did not seem at all to him that he was 94 years old. I kissed his hand, took his wish and in turn wished him always to be healthy and happy.

Toll on the Muslim Population that had to leave Macedonia

The forced migration had significant social, economic, and emotional consequences for those who were uprooted from their homes and communities.

- Displacement and Loss of Homes: The Muslim population in Macedonia who were affected by the population exchange had to leave behind their homes, properties, and ancestral lands. This displacement caused a sense of loss and dislocation, severing their ties to the places they had lived for generations.

- Economic Hardship: Many of the Muslim communities in Macedonia were engaged in agriculture or small-scale businesses. The population exchange disrupted their livelihoods, leading to economic hardship as they had to start anew in Turkey with limited resources and unfamiliar conditions.

- Social Disruption: The population exchange led to the disintegration of tight-knit communities, as families and neighbors were separated during the forced migration. The loss of social support networks and familiar social structures further contributed to the challenges they faced in the new environment.

- Cultural and Linguistic Challenges: Moving to a new country meant adapting to a different culture and language. The Muslim population from Macedonia had to navigate the complexities of assimilating into Turkish society while preserving their own cultural identity.

- Trauma and Memories: The forced migration was a traumatic experience for many, leaving lasting emotional scars on the individuals and their families. The memories of leaving their homeland and the events surrounding the population exchange continued to affect the collective memory of the Muslim population.

- Challenges of Integration: While Turkey was the ancestral home for some of the Muslim communities, others were relocated to regions with which they had little historical or cultural connection. This made integration into the new communities more challenging.

It’s important to note that the toll on the local Muslim population was not uniform and depended on various factors, including the specific circumstances of their migration, the region they were relocated to in Turkey, and their ability to adapt and rebuild their lives in the new setting. The impact of the population exchange had far-reaching consequences, affecting both the individuals who experienced it firsthand and their descendants, shaping the collective identity and memories of the Muslim communities from Macedonia.

Toll on Local Indigenous Population of Macedonia

The Greco-Turkish population exchange of 1923 had a significant toll on the local population of Macedonia, particularly for those who were affected by the forced migration and displacement. The aim was to create ethnically homogeneous nation-states in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

For the Muslim Macedonians who were uprooted and sent to Turkey, the exchange meant leaving behind their homes, land, and communities. Many faced difficult and challenging conditions during their forced migration, with some experiencing violence and hardship along the way. The resettlement in Turkey also presented challenges as they had to adapt to a new environment and culture.

On the other hand, the departure of Muslim populations from Greek-controlled Macedonia left a void, altering the demographic landscape of the region. In some areas, the departure of Muslim communities meant a loss of cultural diversity and historical heritage. It also had economic repercussions, as communities lost skilled labor and knowledge accumulated over generations.

Furthermore, the population exchange left enduring impacts on the collective memory and identity of the people involved. Families were separated, and many carried memories of the traumatic events for generations to come. Overall, the Greco-Turkish population exchange of 1923 had profound consequences for the local population of Macedonia, reshaping communities and leaving a lasting impact on the social, cultural, and demographic fabric of the region.

The arrival of Christian refugees in Macedonia as a result of the Greco-Turkish population exchange of 1923 had a significant toll on the local population of the region. The influx of a large number of refugees created various challenges and changes for both the existing Macedonian population and the newly arrived Christian refugees.

- Strain on Resources: The sudden increase in population put a strain on local resources, including food, shelter, and basic amenities. The existing infrastructure was often not sufficient to accommodate the needs of the incoming refugees, leading to competition for resources and potential social tensions.

- Social and Cultural Impact: The arrival of Christian refugees in Macedonia brought cultural and linguistic differences, which sometimes led to tensions with the local population. There could be clashes over traditions, customs, and language, contributing to social frictions.

- Land Distribution and Displacement: The process of resettling Christian refugees in Macedonia involved land distribution, which could result in the displacement of some local Macedonian inhabitants. This created further tension between the two communities.

- Economic Changes: The arrival of Christian refugees brought both skilled and unskilled labor to the region. This had an impact on the local economy, as it changed the labor market dynamics and might have affected employment opportunities for the local population.

- Political and Administrative Challenges: The integration of a large number of refugees required significant administrative efforts. Local authorities had to manage the distribution of resources, registration of refugees, and the overall process of integrating them into existing communities.

- Cultural Exchange and Assimilation: Despite the initial challenges, the interaction between the Christian refugees and the local population also led to cultural exchange and assimilation over time. Both communities might have adopted aspects of each other’s cultures, contributing to a more diverse regional identity.

It’s important to note that the impact of the refugees on the local population was multifaceted and varied from one area to another. Over time, communities often found ways to adapt and coexist, leading to the creation of new social dynamics in the region.

Toll on the Christian Refugees that settled in Macedonia

The 1923 Greek-Turkish population exchange had profound effects on the lives of refugees who settled in Macedonia. Christians who were resettled in Greek-controlled Macedonia faced challenges in adapting to a new environment. Displaced from their homes in the former Ottoman Empire (Turkey), the Christian refugees had to adapt to a new country, often dealing with economic hardships, social integration difficulties, and the loss of their previous way of life. This population exchange was a complex and emotionally charged process that deeply impacted the lives of those involved.

Integration into Greek society was often complicated by cultural and linguistic differences. The refugees brought diverse experiences and traditions, contributing to the complex mosaic of multiethnic societies that still existed in Macedonia only 10 years after the Balkan War when Greece gain control of the region. Additionally, the demographic changes resulting from the exchange influenced local dynamics and relationships between different ethnic and religious groups.

Many of the refugees had little or no consciousness of being Greek. Their expulsion was based on their adherence to the Greek-Orthodox church. League of Nations officials noted that some refugees spoke little or no Greek and displayed a large variety of languages, dialects, and customs. When locals and refugees first came into contact and realized how very different, they were, they suffered “a traumatic cultural shock”.

The ethnic boundaries separating refugees and their hosts, were sufficient to cause strife and prejudice, particularly as competition for land and livelihood lowered the standard of living for everyone.

The cultural and linguistic differences were more similar in Macedonia and especially in Sklithro-Zelenich. In the first place, Zelenich had just lost 1,100 Muslims in the exchange but, those who came in, could communicate with the indigenous Macedonians since most if not all were bilingual (Turkish and Macedonian). Secondly, both natives and refugees (Majiri in Macedonian) were being assimilated into becoming Greek and they shared similar experiences when dealing with the Greek authorities.

After 1924, a new reality was shaped in Greece, where new populations had to integrate and assimilate overcoming language and cultural differences. Turkish Christian refugees largely settled in land and villages formerly occupied by Muslim Greek minorities who were all forcibly removed from Greece in 1923. Virtually no Muslim Turkish communities remained in Greece, except for Thrace which was exempted from the population exchange.

The exchange of populations had a three-fold effect in legitimizing of a humanitarian disaster. It not only uprooted people from their places of birth, it created refugees who became strangers and in doing so, it also created problems for the indigenous people in the new lands. Thus, actively enforcing the idea of the “pure homogeneous” nation-state upon peoples who came from different ethnicities and cultures who were assimilated through religion.

Both the Greek and Turkish nations developed based on religious not ethnic nationalisms. According to this model of national ideology, cultures were nationalized by religion and religion became a criterion of national identification and mobilization. Thus, this can be understood as an attempt at social engineering in which certain customs and morale (that is sociocultural, linguistic, and historical characteristics) were to be used for creating a different national awareness. Social engineering was used as a tool to assimilate the Orthodox populations of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds by Hellenizing them.

Social Engineering

It’s important to note that the consequences of the population exchange were multifaceted and evolved over time, shaping the sociopolitical landscape of Greek (newly aquired) Macedonia in the decades that followed.

Mainstream Greek historiography, political discourse, and popular representations alike, designate the refugees of the war of 1922 between Turkey and Greece as ‘Asia Minor Hellenism’. Current scholarship challenges this abstract identification and have demonstrated that it has been fabricated mainly after the “so called – Catastrophe” in the context of a hegemonic nationalist discourse, associated with the nation building process in Asia Minor and the Balkans.

One hundred years after the event of 1922, issues surrounding the identities of the Christian refugees are still controversial. The controversy arises from rifts between two discursively interwoven yet differently positioned and differently animated narratives: on the one hand the narrative of nationalism, intentionally activated and politically informed, and on the other the first-hand narratives, the embodied recollections of the ordinary refugees.

Although these two discourses temporarily meet, cross cut or reinforce each other, in the long run they appear irreconcilably opposed. What makes this partiality so deep is not only the disagreement about what happened in the past and what the past was, but uncertainty about whether the past is actually a past, over and concluded, or whether it continues, albeit in different forms. Indeed, current disputes between Turkey and Greece revitalise issues concerning the interpretation of their recent national histories, state policies regarding the treatment of Turkey’s Christians and Greece’s Muslims, and the implementation of the Lausanne Treaty that followed the disastrous war.

The expulsions of Muslims from Greece helped free up the farmlands of Greece’s Macedonian region, where many of the Christian Orthodox Turkish nationals were then settled. The assets of the expelled Muslim families were essential in securing foreign loans that Greece needed to provide material support for its refugee population, in the face of considerable skepticism of Greece’s credit-worthiness by the international banking sector. Foreign investment in Greece was readily facilitated by the substantial assets left behind by expelled Muslims, which Athens then deposited as securities for desperate loans. From this perspective, the agreement to expel its Muslim population as an almost inevitable policy option for Greece.

While current scholarship defines the Greek-Turkish population exchange in terms of ethnic identity, the population exchange was much more complex than this. Indeed, the population exchange, embodied in the Convention Concerning the Exchange of Populations at the Lausanne Conference of January 30, 1923, was actually based on religious identity.

Bernard Lewis claims that the population exchange “was not a repatriation of Greeks to Greece and of Turks to Turkey but a deportation of Christian Turks from Turkey to

Greece and a deportation of Muslim Greeks from Greece to Turkey.” Lewis underlines the dissimilarity between the incoming and native populations in both countries.

In Greece, the Greek state, reaped the benefits from the resettlement challenge and considered this as an opportunity to Hellenize the ethnic structure of the “New Lands – Macedonia” that had been acquired from the Ottoman Empire in 1912-1913. The resettlement task that the state undertook in Greek Macedonia under the auspices of the League of Nations had social, political, ethnological and economic impact.

In her book, Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia: The Rural Settlement of Refugees 1922-1930, Elisabeth Kontogiorgi explores, refugee resettlement and integration; the role of international organizations in Greek Macedonia; the nation-building process in Greece through the Hellenization of Greek Macedonia as the result of resettling 800,000 refugees of supposedly Hellenic origin; and the impact of the resettlement in the region on the “non-Greek-speaking” (as Kontogiorgi calls) inhabitants of the region.

The establishment of Greek refugees into this “sensitive” region was in securing the predominance of the Greek element in Macedonia and eradicate the possible territorial aspirations of the neighboring states and of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). The impact of the resettlement on Greek Macedonia was not limited to social or political matters. With the arrival of the refugees from different regions and different backgrounds the population exchange ethnologically and demographically transformed Macedonia as well. This resulted in the Hellenization of the toponyms of the region in 1927. Not only, did they ethnically cleanse Macedonia of its Muslim population, but also, it’s indigenous Macedonians through its assimilating Hellenization policies.

These policies of demographic and social engineering of ethnic Macedonians will be futher analysed in preceding sections which continue to the 21st century. The population exchange made it legally possible for both Turkey and Greece to cleanse their religious minorities in the formation of the nation-state. Nonetheless, ethnicity was utilized as a legitimizing factor in marking ethnic groups as Turkish or as Greek in the population exchange. As a result, the Greek-Turkish population exchange did exchange the Christian Orthodox population of Anatolia, Turkey and the Muslim population of Greece.

The heterogeneous nature of the groups under the nation-state of Greece and Turkey is not reflected in the establishment of criteria formed in the Lausanne negotiations. This is evident in the first article of the Convention which states: “As from 1st May, 1923, there shall take place a compulsory exchange of Turkish nationals of the Greek Orthodox religion established in Turkish territory, and of Greek nationals of the Moslem religion established in Greek territory.” The agreement defined the groups subject to exchange as Muslim and Greek Orthodox. This classification follows the lines drawn by the millet system of the Ottoman Empire. In the absence of rigid national definitions, there was no readily available criteria to yield to an official ordering of identities after centuries long coexistence in a non-national order.

Video and Web Links to the Population Exchange:

Al Jazeera Media Network (24-hour English-language news channel) https://www.aljazeera.com/program/al-jazeera-world/2018/2/28/the-great-population-exchange-between-turkey-and-greece

Florína FaceBook by Cemal Şenses – many old pictures https://www.facebook.com/groups/566994603444909/?_rdr

SERHÍRA – Bolg with many pictures of Turkish refugee families. https://serhira.blogspot.com/2023/

Turkish YouTube video: Immigration History Documentary

Greek YouTube video: Exchange Documentary

Sources:

Ağanoğlu, H. Y. (2023, January). Balkanlar’dan Türkiye’ye Göçler (Migrations from the Balkans to Turkey). Türk Kızılay Akademi. https://kizilayakademi.org.tr/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/balkanlardan_turkiyeye_gocler_web.pdf

Agelopoulos, Georgios (2010). “Contested Territories and the Quest of ethnology: Peoples and Places in Iżmir 1919–1922”. In Spatial Conceptions of the Nation: Modernizing Geographies in Greece and Turkey, edited by Nikiforos Diamantouros, Thalia Dragona and Çağlar Keyder, 181–299. London and new York: I.B. Tauris Academic studies. https://mahabbet.uom.gr/Projects/Documents/NationBuilding/Quest%20for%20Ethnology%20G.%20Agelopoulos%20(CORRECT).pdf

Bakiler, O., & Kizilkaya, S. (2022, January 30). Türkiye’yi ve Yunanistan’ı Değiştiren Anlaşma: Mübadele (The Agreement That Changed Turkey and Greece: Population Exchange). VOA Türkçe. https://www.voaturkce.com/a/turkiye-yi-ve-yunanistan-%C4%B1-degistiren-anlasma-mubadele/6417052.html

Bosnakhaber. (2015, January 5). Marmara Bölgesine Göç Eden Balkan Göçmenlerinin Yerleşim Yerleri (Settlements of Balkan Immigrants to the Marmara Region). bosnakhaber.com. https://bosnakhaber.com/marmara-bolgesine-goc-eden-balkan-gocmenlerinin-yerlesim-yerleri/

Bursa Büyükşehir Belediyesi. (2014, December 3). Göç Tarihi Belgeseli (Immigration History Documentary) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7b7eYBBCbE&t=232s

Christodoulou, L. P. (2022). 1922 – 2022 – 100 Years since the Asia Minor Disaster – The tragic uprooting of the Christian populations of the East – The rescue routes to Greece. http://www.kemipo-neaionia.gr. https://kemipo-neaionia.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/XERIZOMOS_1922_2022_KEMIPO.pdf

Gavra, E. G. (2009). “Settlements of refugees, transformation of regions in Greece” in: J. Koliopoulos, I. Michailidis (editorship) The refugees in Macedonia.” Hoi prosphyges stē Makedonia: Apo ten tragōdia, sten epopoiia.

Giorgis, A. (2016, May). 1922 Asian Minor Refugees [Photograph]. istorika-ntokoumenta.blogspot.com. http://istorika-ntokoumenta.blogspot.com/2016/05/1922-to.html

Goularas, G. B. (2012). 1923 Türk-Yunan Nüfus Mübadelesi Ve Günümüzde Mübadil Kimlik Ve Kültürlerinin Yaşatilmasi (1923 Population Exchange Between Turkey and Greece: the Survival of the Exchanged Population’s Identities and Cultures). Alternatif Politika, 4(2). https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=567439

Goularas, G. B. (2012). 1923 Türk-Yunan Nüfus Mübadelesi ve Günümüzde Mübadil Kimlik ve Kültürlerinin Yaşatılması (1923 Turkish-Greek Population Exchange and the Survival of Exchanged Identities and Cultures Today). Alternative Politics, 4(2), 18. https://alternatifpolitika.com/eng/makale/1923-turk-yunan-nufus-mubadelesi-ve-gunumuzde-mubadil-kimlik-ve-kulturlerinin-yasatilmasi

English Translated Version: https://alternatifpolitika-com.translate.goog/eng/makale/1923-turk-yunan-nufus-mubadelesi-ve-gunumuzde-mubadil-kimlik-ve-kulturlerinin-yasatilmasi?_x_tr_sl=tr&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=sc

Goularas, G. B. (2012, July). Harita 1. Mübadillerin Türkiye’de Dağılımı 1923-1925 (Map 1. Distribution of Exchanges in Turkey 1923-1925) [Map]. acarindex.com. https://www.acarindex.com/dosyalar/makale/acarindex-1423869211.pdf

Goularas, G. B. (2021). [Photograph]. Central and Eastern European Online Library. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=567439

Günhan, A. (2017, April 18). The Karamanlides: Anatolia’s forgotten orthodox turks. Daily Sabah. https://www.dailysabah.com/feature/2017/04/18/the-karamanlides-anatolias-forgotten-orthodox-turks

GreekWorldHistory. (2016, March). Christian Refugees from Asia Minor [Photograph]. greekworldhistory.blogspot.com. http://greekworldhistory.blogspot.com/2016/03/blog-post_20.html

ICRC. (1923). [Photograph]. International Committee of the Red Cross. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/misc/5gke3d.htm

ICRC. (2005, January 25). The Turkish-Greek conflict (1919-1923). International Committee of the Red Cross. https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/resources/documents/misc/5gke3d.htm

Iğsiz, A. (2008). Documenting the Past and Publicizing Personal Stories: Sensescapes and the 1923 Greco-Turkish Population Exchange in Contemporary Turkey. Journal of Modern Greek Studies 26(2), 451-487. https://doi.org/10.1353/mgs.0.0035.

Inanc, Y. S. (2023, January 30). Turkey-Greece population exchange still painful for those yearning for a lost past. Middle East Eye. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/turkey-greece-population-exchange-painful-yearning-lost-past

Istoriaka Dokoumenta. (2016, May 19). 1922: To Μίσος των ντόπιων Ελλαδιτών εναντίον των Ελλήνων Προσφύγων της Μ.Ασίας | ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ – ΘΕΩΡΗΤΙΚΑ ΚΕΙΜΕΝΑ. ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ – ΘΕΩΡΗΤΙΚΑ ΚΕΙΜΕΝΑ |. https://istorika–ntokoumenta.blogspot.com/2016/05/1922-to.html#comment–form

Istorika Dokoumenta. (2016, May 19). [Photograph]. Istorika-Ntokoumenta.blogspot.com. http://istorika-ntokoumenta.blogspot.com/2016/05/1922-to.html#comment-form

James, A. (2001, December 31). Memories of Anatolia : Generating Greek refugee identity. OpenEdition Journals. https://journals.openedition.org/balkanologie/720

Karamanlides Travelling in their Carts [Photograph]. (2017, April 18). http://www.dailysabah.com. https://www.dailysabah.com/feature/2017/04/18/the-karamanlides-anatolias-forgotten-orthodox-turks

Kitroeff, A. (2012, January 1). Asia Minor refugees in Greece: History of identity & memory 1920s-1980s. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/37523568/Asia_Minor_Refugees_in_Greece_History_of_Identity_and_Memory_1920s_1980s?auto=download

Kontogiorgi, E. (2006). Population exchange in Greek Macedonia. Google Books. https://books.google.ca/books?id=43A6BS9khccC&pg=PA9&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false

Kotzaeridis, G. (2022, July 29). 1922-2022. 100 χρόνια από τη Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή – Μαρτυρίες προσφύγων που έζησαν στο πετσί τους τη Μικρασιατική Καταστροφή – 1922-2022. 100 years since the Asia Minor Disaster – Testimonies of refugees who lived through the Asia Minor Disaster. Imerisia-ver.gr.

Lausanne Exchanges Exchange Agreement , Lausanne Exchanges Foundation, www.lozanmubadilleri.org.tr/mubadele-sözmeleri/ Access Date: 30.11.2020

League of Nations. (1925). LEAGUE OF NATIONS Treaty Series. United Nations Treaty Collection. https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/LON/Volume%2032/v32.pdf

Levantine Heritage. (2004). Views of Greek refugees leaving Smyrna. [11 Photographs of Christian Evacuation]. Levantine Heritage Foundation: Research – Education – Preservation. https://www.levantineheritage.com/evac.htm

Levantine Heritage. (2004). Evacuation Pictures [11 Photographs]. levantineheritage.com. http://www.levantineheritage.com/evac.htm

Limantzakis, G. (2017, January). The first talks of a Greek-Turkish population exchange in 1914 and the political and military reasons behind it, Uluslararası Mübadele Sempozyumu Bildirileri, 30.1-1.2.2017, Kemal Arı (ed.), Tekirdağ 2017 [Paper presentation]. Uluslararası Mübadele Sempozyumu .

Mandratsi, C. (2019, March). The relations between refugees and locals in the mixed villages of the Prefecture of Florina. DSpace Home. https://dspace.uowm.gr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/1368/%CE%A7%CE%A1%CE%99%CE%A3%CE%A4%CE%99%CE%9D%CE%91%20%CE%9C%CE%91%CE%9D%CE%A4%CE%A1%CE%91%CE%A4%CE%96%CE%97.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Mann, I., & Özsu, U. (2015, October 14). A group of refugees leave the Samanli-Dag Peninsula, on a boat they boarded with the help of the Turkish Red Crescent [Photograph]. criticallegalthinking.co. https://i0.wp.com/criticallegalthinking.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Refugess-leave-Samanli-Dag-Peninsual.jpg

Morack, E. (2017). The dowry of the state: The politics of abandoned property and the population exchange in Turkey, 1921-1945. University of Bamberg Press. https://refubium.fu-berlin.de/bitstream/handle/fub188/5979/Dissertation_Morack.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Murard, E., & Sakalli, S. O. (2018, June). Mass Refugee Inflow and Long-Run Prosperity: Lessons from the Greek Population Resettlement. docs.iza.org. https://docs.iza.org/dp11613.pdf

Οι πρόσφυγες του ’22 στη Φλώρινα (The Refugees of ’22 in Florina-Lerin (December 19, 1922). Learn for Change. https://www.learn4change.gr/archives/6302

Pentzopoulos, D. (2021). The Balkan exchange of minorities and its impact upon Greece. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Perchanidou, A. (2018, November). The Greek Refugees from Kars in Batumi and their final settlement (1919-1923. repository.ihu.edu.gr. https://repository.ihu.edu.gr/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11544/29427/A.Perchanidou_bss_15.4.2019.pdf?sequence=1

Rakopoulos, A. (2022, April 13). Σκλήθρο – (Ζέλενιτσ*) – Σε απάντηση μιας χυδαιότητας, επικίνδυνων, σκοτεινών, βρωμερών, τυμβωρύχων…. ΠΕΡΙΣΚΟΠΙΟ. https://eperiskopio.blogspot.com/2022/04/blog-post_98.html

Refugee Population Exchange [Map]. (2022, September 27). https://eleftherostypos.gr. https://eleftherostypos.gr/ellada/100-chronia-apo-ti-mikrasiatiki-katastrofi-i-proti-apografi-prosfygon-tou-1923#article-images-2

Şenses, C. [FLORÍNA]. (2023, October 10). Log into Facebook [Public Comment of Zeleniç by Özel Gündoğan]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/566994603444909

Şenses, C. (2017, May 6). Facebook. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/566994603444909/search/?q=Zeleni%C3%A7

Şenses, C.l [FLORÍNA]. (2022, April 12). 1924 yılı.Mübadeleden bir resim (Year 1924. A picture from the exchange). Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=5828118813882603&set=g.566994603444909

Settlements of Balkan Immigrants to the Marmara Region [Photograph]. (2015, January 5). Bosnakhaber.com. https://bosnakhaber.com/marmara-bolgesine-goc-eden-balkan-gocmenlerinin-yerlesim-yerleri/

Shields, S. (2016). Forced Migration as Nation-Building: The League of Nations, Minority Protection, and the Greek-Turkish Population Exchange. Journal of the History of International Law / Revue d’histoire du droit international, 18(1), 120-145. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718050-12340054

Serhira. (2021, June 1). Exchange [Painting]. serhira.blogspot.com. https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgAolvgicurgkl1U6jNHV57eKDYYRxMTMGNKbAthoraOP35pO54ApJrrWgCvX9h4fd-YyL14U0Jb4prqT8HpD9tL3umaBGzqIA3uPQAS2pBETjG26EaWTkkQmISE5liLVJoalizFNsrfm8/s1600/12932740_196095574105940_574814489211377795_n%255B1%255D.jpg

Stanishevski, S. [Stanishevski Slavco]. (2021, December 18). A family having breakfast on the road, looking for a new home. Expelled from the Aegean part of Macedonia, exiled by the Greeks in 1925 [Photograph]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=1155691811631309&set=gm.2560186420792374

Tanis, Fatma. “The lost Identity of Izmir”. In Carola Hein (ed.) International Planning History Society Proceedings, 17th IPHS Conference, History-urbanism-Resilience, Tu Delft 17-21 July 2016, V.01 p.381, Tu Delft open, 2016. https://journals.open.tudelft.nl/iphs/article/view/1212/1816

The Asia Minor catastrophe. (2022, September 14). Discover Europe’s digital cultural heritage | Europeana. https://www.europeana.eu/en/blog/the-asia-minor-catastrophe

United States Office Of Strategic Services. Research And Analysis Branch. (1945) Transfers of population in Europe since. Washington. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/sd49000323/.

Unknown photographer. (1922, August 28). Greek refugees at the Port of Moudania, Asia Minor (today, Mudanya, Turkey). From the archives of the Society of Friends of the People, Athens, Greece. Wikimedia. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/88/Asia_Minor_Moudania_Port_Greek_refugees_28_August_1922.jpg

Yildirim, O. (2006). Diplomacy and displacement: Reconsidering the Turco-Greek exchange of populations, 1922-1934. Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/4394667/Diplomacy_and_Displacement_Reconsidering_the_Turco_Greek_Exchange_of_Populations_1922_1934