The memorized customs, beliefs, and rituals of the peoples of Macedonia have occupied a prominent place among the indigenous inhabitants of the village of Sklithro, originally named Zelenić around 1396 CE. This collective memory has been the core of the folk culture that has been preserved, protected, and passed down for millennia through the ritual performances of living folk traditions that came from the settlement called Sebaltsi/Seblatsi before the Ottoman occupation. It is a sure sign and example of the continuity of the culture, beliefs, and traditions of the indigenous people of the village of Sklithro (and the rest of Macedonia) having originated before Christianity. Many of these ritualized performances have been modified in Christian times and have taken on numerous Christian elements, symbols, meanings, and functions.

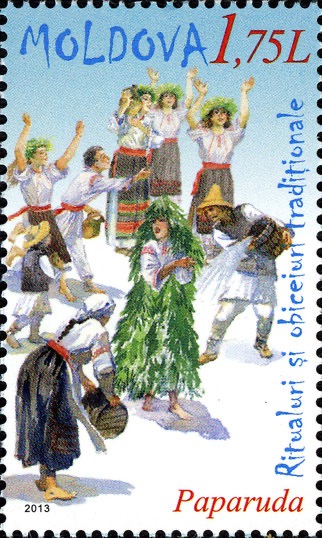

The “Cult of Dudule” (also known as Paparuda/Peperuda/Dodola in other parts of the Balkans) was described as a pagan rain-making ritual. In 1925, Sir Arthur Evans, a British archaeologist and pioneer in the study of Aegean civilization in the Bronze Age, most famous for unearthing the palace of Knossos on the Greek island of Crete, first described a pagan rain-making ritual he witnessed in a village north of Florina. This pagan rain-making ritual was last witnessed in Sklithro in the 1960s.

The “Dudule” rain-making ritual in Sklithro-Zelenić and in Macedonia, was not related to any festival or date in the calendar but was performed sporadically in times of drought. The dry season usually lasts from spring through the summer, from the start of March to August. This ritual descends from polytheistic practices long before the arrival of Christianity. Every Balkan culture has its own rain-making ritual, based in sympathetic magic and mimesis (on the belief that one thing or event can affect another at a distance as a consequence of a sympathetic connection between them).

The Balkan rainmaking customs themselves go by different names. They are usually referred to as the Paparuda/Peperuda rituals, after the name of the Slavic goddess of rain, wife or consort of the Slavic sky-God Perun. According to some researchers, these pagan rites of worship are thought to be of Thracian origin, others claim that they go even further back to the original ancient Macedonians, the Pelasgians. The names of these Peperuda/Paparuda/Dodola – including their many variants, such as Dudula, Dudulica, Dodolă, Tuntule, Dudule, Didule, Gugule, Djudjule.

With the break-up of Macedonia in 1913, these newly annexed territories became part of the modern expanded territories of the nation states of Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia. As pressure grew to assimilate the indigenous peoples of Macedonia, the customs, beliefs, and traditions began to fade as they were outlawed by the states and banned by the dominant Orthodox churches as being pagan. Right up to the Turko-Greek population exchange of 1923

The pagan rain-making ritual was last performed in Sklithro in the late 1960s as the Greek military junta from 1967 – 1974 put a stop to most indigenous Macedonian customs which would slowly resurface in the early 1990s with the independence and formation of the new state named the Republic of Macedonia (formally known as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia one of the six constituent countries of the post-WWII Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and a nation state of the Macedonians).

Rain-making Ritual of Paparuda/Peperuda

According to informants from Sklithro living in Canada, “Paparuda/Peperuda” is the ritual and the individual performing the act is called the “Dudule/Djudjule/Dodole.”

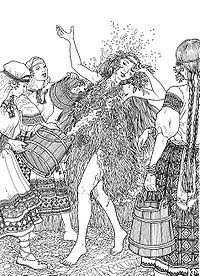

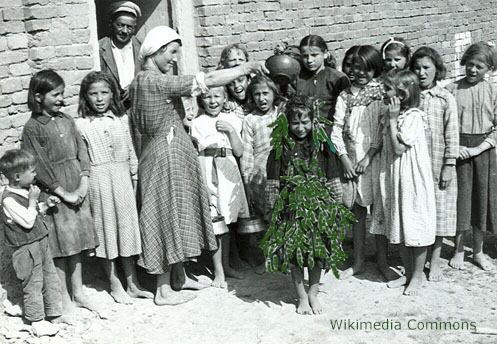

In times of drought, villagers would worship the old gods by performing the “Dudule” dance and summoning rain. The lead performer was usually a young orphan girl, a virgin who was stripped naked and ‘dressed’ in the branches of a sacred tree. The girl picked and trained by the Shamanka/s was dressed by an older woman or women in the branches of willow, elder, maple, oak, or in springs of barley or lilac and various herbs. Originally this girl would have to be naked but in the twentieth century she would wear old clothing underneath. She would also have a group of younger girls who would follow and assist her throughout the whole ritual.

The girls were led by the oldest girl, the “Dudule,” and would first go to “Rideau” – the area below the evergreen trees and gather the sacred tree branches; from there they would walk down to the riverbank at “Yame” and the “Dudule” would dip in the “Stara Reka” (river) and perform a customary initial chant song (ritual) containing the chorus below:

Cut a pine branch prune a rod

Beat out the demons call up God

Strip an ash-bough peel a wand

Whip out our ghosts to back-of-beyond

Find a hazel-fork dowse for a well

Flush out the dead clean out hell

Chant for Rain:

“Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

Neka vrne, neka grme

Neka paǵaat kapki rosa

Za da može da se rodi vinožitoto.“

In the English

“Oh God, Dear God

Let it rain, let it thunder

Let drops of dew fall

So that the rainbow can be born.”

The first words of the song identify or correlate their own action of walking over or through the fields with that of the movement of clouds across the sky. It is implicit here that the Dudulas are like clouds, in that both are dispensers of rain. The first line of the song also means ‘Fly, fly butterfly.’ The words of the song call on God to pour down rain, to enable the fields to yield grain for bread, as well as wine, hemp, and basic victuals (food).

Here follows a song recorded in the first half of the 19th century in he Mavrovo region of North-Western Macedonia:

Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

We go through the village, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le!

and the clouds over the sky, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le!

We go faster, the clouds go faster, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le!

The clouds are ahead of us, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le!

The wheat, the wine is shared, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le!

(Karadzic 1841)

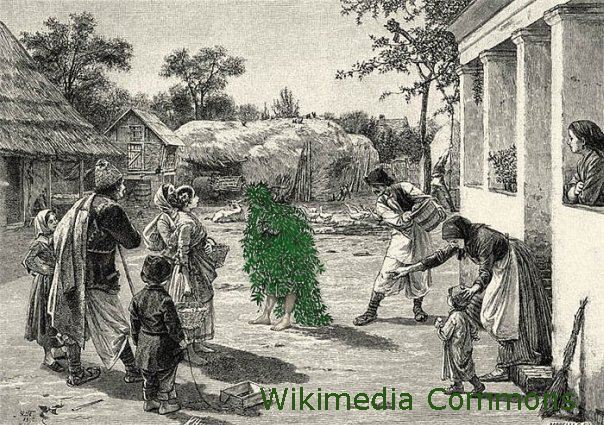

Once they completed their initial ritual at “Rideau,” the girls would then proceed and visit each home of the village to dance and sing the special “Dudule” songs. The lead girl would dance barefoot, singing and dancing to an ancient song. The other girls would sing the verses of the ballad dedicated to rain, they would squirm, raising their hands to the sky and stamping their feet hard on the ground to awaken the Earth. Mothers and elderly women would walk around them, giving rhythm to the dance with improvised drums with pots and throwing cold water on the group leader while she would spin around and sprinkle it all over the yard. The girls were then rewarded with gifts of flour, food and sometimes even money.

The rain ritual contained many aspects and elements: speech, including songs, prayers, and invocations; dancing, when calling at houses in the village; singing, both solo and chorus, unaccompanied by instruments; and performance. Features endemic to this Macedonian custom in Sklithro-Zelenić were conducted in the month of August, on the fourth day of the week, a Thursday.

This ritual was performed in every part of Greek Macedonia especially in the Florina and Kastoria regions and it is still performed in certain rural parts of the Republic of Macedonia. It is a sure sign and example of the continuity of the culture, beliefs, and traditions of the indigenous people of the village of Sklithro (and the rest of Macedonia) having originated before Christianity.

Despite the many variations found in the details of the rain-making rituals throughout the Balkans (and not just from region to region but sometimes from one village to the next), the underlying unity among the people is undeniable. In the village of Zelenić, both Christians and Moslems practised the ritual right up to the 1923 Turko-Greek population exchange. The magic of rain was called “Bride” or, in Turkish, “Gelindjik”, (“Gelindjik”) or “bride of the rain”.

According to the old way and accompanied by a Turkish melodic text, “A poor child, about twelve years old, the they covered with rags, to which they attached branches and shoots. The face of the child they covered it with a cloth and put one on her head a sieve. After that, the children took her into the village. The villagers sprinkled it with water, knelt and sang in groups.

Even the Asia Minor settlers who settled in the village (after the Muslim inhabitants left) would participate in this ritual using Turkish words.

Cifischiler yagnur ister,

okuzler saman ister,

oksizler ekmek ister,

ver allahin ver!

Οι γεωργοί θέλουν βροχή,

Τα βόδια θέλουν άχυρο,

Τα ορφανά θέλουν ψωμί,

Δώσε, Θεέ μου, δώσε!

Farmers want rain, The oxen want straw, Orphans want bread, Give, my God, give!

From the end of the Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and the second half of the twentieth century, Macedonia’s rich folk culture went through a collapse, as did those of most neighbouring communities. Rural areas were ravaged, as were the ritual and magical customs of village folk culture. These ritual performances became all the harder to keep up any folk customs, myths, or rituals at all. The overall result has been that many customs have gradually faded from popular collective memory because of wars, assimilation policies for nation states and state sponsored Christian practices.

Despina Posderkos and Durivitsa Singatava were the last to perform the Peperuda. As the ritual began to fade due to the banning of indigenous Macedonian cultural traditions and rituals, there were no longer any young girls being trained in the old customs. As such, Despina and Durivitsa became the last keepers of the custom/belief of Peperuda as the village “shaman-kas” who directed spiritual energies into the physical world. A Shaman-ka is a person regarded as having access to, and influence in, the world of good and evil spirits.

Folk Rituals and Customs

The earliest records of Macedonian spring and summer customs and rituals of the Dudule/Dodole type were made by Dimitar Miladinov (1810–1862) and his brother Konstantin (1830-1862), which they published in their collection of folk-songs in 1861. Another great collector and authority was, Marko Cepenkov (1829–1920).

The ritual integrated Christian overlays, beneath which imprinted traces of pagan beliefs and customs are still evident. For example, to invoke a good harvest in any particular year, women traditionally prayed for rain to “give birth.” Imagery of this kind, which occurs in various folk-rituals, the fertility of the land is symbolically identified with both the perpetuity of the human community and their own personal desire to find a husband and have children.

It seems that both rainmaking rituals and women’s songs are among the oldest folk customs. Motifs from both have also been transferred and assimilated into many other spring and summer rituals involving the natural cycle, blessings for the year—and therefore rain too, without which nature would not produce rich and fertile harvests.

In their invocations of fertility abundance, these evidently contain within them the core of all the other spring and summer magical rituals. In the ritual of rainmaking, such as washing in the morning dew; walking down to the riverbank and dipping in the stream; and singing archaic chants to invoke the rainbow. What is more, just as performance of the rain-ritual predicts rain that will ensure fertility, so it is believed that failure to perform the ritual could cause a dry and barren year. The Balkan countries have maintained a close link with the ancient pagan traditions. Almost all customs originated before the Roman incursions into the peninsula. The peoples who have left the most rituals are the ancient Macedonians who practised pagan cults that resisted the advent of Christianity. One of the most mystical rituals is the Paparuda/Peperuda, an ancient rite to invoke rain.

“Dodole” songs are typical ritual songs used to perform during summer dry seasons. Young girls masked themselves with branches and leaves (as symbol of vegetation exuberance).They used to visit village houses and perform “dodole” ritual (singing “dodole” songs and dancing ritual dance).As respond to a ritual performance, the master of the house would come out from house and throw some water on dancers, which is ancient way of invoking the spirits of rain. “Dodole” ritual originates from pre-Christian times and represents the oldest Slavic tradition.”

Here is an example of a Dodole song performed in Zagreb Croatia but with Macedonia lyrics of the “Dodole/Dudule” song:

Our young girl begs god, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

Rain with small drops to let go, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

Our fields to flood, dudule, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

And to bear us wheat, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

And corn heads in every house, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

She begged, and she begged, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

And rain with small drop started raining, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

Flooded our fields, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

And it had borne us wheat, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

And corn heads for every house, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

Our young girl begs god, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

God, God, dear God, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le

Give us, give us, dear God, Oy-dudu, oy-dudu-le.

Examples from other parts of Greek Macedonia

In Grevena, in a period of drought they cover with leaves of boxwood and flowers a poor girl, aged eight to twelve, and they go then barefoot with a pot on top of the head inside the village. In front of each yard, the “Dudule” dances, while the other children they sing their supplication. The spatialwomen of each house appear in front at their doors, and sprinkle the girl with water and give her bread, flour or money.

In Nymfaio (Neveska), in times of drought, the Vlachs build one human figure from rags and straw. The face is formed with one scarf, on which the mouth, nose and eyes are painted. After they put a tuft of straw on them. When everything is ready, they fasten the doll on a wooden cross and then walk around in the settlement, where they sprinkle it with water. The girls who accompany, meanwhile, sing and gather oil, flour and various foods for a zelnic (pie), which they bake, together, the next day (Sirma Kourlina).

In Epanomi of West Halkidiki, in a period of drought, they take a ten-year-old orphan girl to a meadow where they cover her with boxwood leaves and cover her head with a sieve-like fabric and go around the village. In the front at the door of each yard the housewife appears and they throw flour and water on the head of the girl. The “Dudule” dances with short rhythmic movements on the spot, while the women and girls who accompany her sing and dance Then they accompany the little one from yard to yard. They go door to door, sprinkle the child with water and give her cheese, eggs, bread or money.

Apparently, in Asvestochori of Thessaloniki, “Parparnuna/Perperuna” is still celebrated today. Two or three old women choose a poor girl, preferably an orphan for the presentation of the ritual. This they search, in great secrecy, so that no one will know about which child they pick. Then they take her barefoot, dressed only in a shirt to a nearby river. There, while she is in the water, they cover her with branches and leaves so that the eyes look outwards. In this disguise, she is led by one of the old women in the village, where the villagers sprinkle the child with water and sing her song together “Dudule”. After that, the little girl gets a lot of gifts. The original wording of the song is Macedonian. Because, however, only a few seniors understand the Macedonian dialect, “Dudule” is sung in both Greek and Macedonian.

Origin of the Custom

The Balkan countries have maintained a close link with the ancient pagan traditions linked to the rural dimension. Almost all customs originated before the Roman incursions into the peninsula and before Christianity. The peoples who have left the most rituals are the ancient Macedonians who practised pagan cults that resisted the advent of Christianity.

Today, the rain-making ritual of Paparuda/Peperuda with the dance of the Dudule can be seen in some rural parts of the Republic of Macedonia, Albania, Bulgaria, parts of northern Greece (Macedonian region), Moldavia, Romania, and the Ukraine. You can also click on the links below to view and hear the songs performed in a number of Balkan countries.

Sources:

Burns, R. (2017). Rain and Dust. Studia. https://sms.zrc-sazu.si/pdf/11/SMS_11_Burns.pdf

Djorlev, Z. (2010, February 5). Zoran Dzorlev – Tradicionalen obicaj: Dodole [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X0BgBEtnK4s

Dragnea, M. (2014, March 5). The Thraco-Dacian origin of the Paparuda/Dodola rain-making ritual, Brukenthalia ACTA Musei, No. 4, 2014. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280977102_The_Thraco-Dacian_Origin_of_the_PaparudaDodola_Rain-Making_Ritual_Brukenthalia_Acta_Musei_No_4_2014

Dragnea, M. (2014, March). Peperuna [Photograph]. researchgate.net. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Peperuna-at-Bulgarians_fig6_280977102

Gaston. (2014). Macedonian Folklore – Oj, dodole (Rajna Spasovska) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sK-QX_mnq6w

Haland, E. J. (2001). Rituals of Magical Rain-Making in Modern and Ancient Greece: A Comparative Approach. NKUA: Department of History and Archaeologypage. https://en.arch.uoa.gr/fileadmin/arch.uoa.gr/uploads/images/evy_johanne_haland/cosmos_17-2_haland.pdf

Hapon, M. (2015, August 26). Perperuna’s Dance [Photograph]. wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/37/Taniec_Perperuny.jpg

Kontaxi, L. (2016). Εθιμικές εκδηλώσεις στο χώρο της Βαλκανικής Το Λαϊκό δρώμενο του Λαζάρου “Customary events in the Balkans The Folk Event of Lazarus”. PSEPHEDA – System Offline. https://dspace.lib.uom.gr/bitstream/2159/19395/1/KontaxiLamprini_Phd2016.pdf

ΚΟΥΚΟΥΛΕΤΣΟΥ ΚΑΛΛΙΟΠΗ, X. (2012, March 6). Καλλιόπη – Χριστίνα Κουκουλέτσου – Η Περπερούνα. Εκπαιδευτικές Κοινότητες & Ιστολόγια ΠΣΔ. https://blogs.sch.gr/koukoule/2012/03/06/%CE%B7-%CF%80%CE%B5%CF%81%CF%80%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%8D%CE%BD%CE%B1/

ΚΟΥΚΟΥΛΕΤΣΟΥ ΚΑΛΛΙΟΠΗ, X. (2012, March 6). Τὸ ἔθιμο τῆς Περπερούνας “The ritual of Perperuna” [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uU0K-UOtgwA

Kraljica, T. (2019). Vrelo – Oj dodole, mili boze [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sg8WlQTi6I0

Kulavkova, K. (2020). A Poetic Ritual Invoking Rain and Well-Being: Richard Berengarten’s In a Time of Drought. Anthropology of East Europe Review, 1(37).

Predić, U. (1892). Watering of Dodola [Photograph]. wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cd/%22Watering_of_Dodola%22_by_Uro%C5%A1_Predi%C4%87%2C_published_in_magazine_%22Orao%22_in_1892.jpg

Prokosch Kurath, G. (n.d.). Dance Relatives of Mid-Europe and Middle America. The Journal of American Folklore, 69(273), pp. 286-298. https://www.jstor.org/stable/537145

Quixote, D. (2012, March 8). Ancient Rituals from Different Cultures. All Empires: Online History Community. https://www.allempires.com/forum/forum_posts.asp?TID=31330

Ravijojla, V. (2019, January 24). Додоле (Dodole). vila-ravijojla. https://vila-ravijojla.tumblr.com/post/182276816018/dodola-%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%B0-is-the-slavic-goddess-of-rain-and

Unknown. (1950). Rite of Peperuda [Photograph]. wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b4/%D0%9F%D0%B5%D0%BF%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B0_%D0%B2_%D0%94%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%80%D1%83%D0%B4%D0%B6%D0%B0_1950.jpg

Unknown. (2009, June 21). Goddess Dodola. Goddesses and Gods. https://goddesses-and-gods.blogspot.com/2009/06/goddess-dodola.html

Velickovska, R. (2009). Musical Dialects in the Macedonian Traditional Folk Singing. Institute of Folklore Marko Cepenkov, Skopje, 4, p. 45.

Viaggi Cultura. (2020, September 5). Paparuda, francobollo moldavo [Photograph]. viaggicultura.it. https://www.viaggicultura.it/2020/06/14/paparuda-la-danza-della-pioggia-dei-balcani/

Vonitsas. (2016, October 15). Η ΜΠΑΡΜΠΑΡΟΥΣΑ Η ΠΕΡΠΕΡΟΥΝΑ (ΠΕΤΑ ΑΡΤΑΣ) | ΔΗΜΟΤΙΚΟ ΣΧΟΛΕΙΟ ΑΓΙΟΥ ΝΙΚΟΛΑΟΥ ΑΚΤΙΟΥ-ΒΟΝΙΤΣΑΣ. Εκπαιδευτικές Κοινότητες & Ιστολόγια ΠΣΔ. https://blogs.sch.gr/dimstnik/2016/10/15/%CE%B7-%CE%BC%CF%80%CE%B1%CF%81%CE%BC%CF%80%CE%B1%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%85%CF%83%CE%B1-%CE%B7-%CF%80%CE%B5%CF%81%CF%80%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%85%CE%BD%CE%B1-%CF%80%CE%B5%CF%84%CE%B1-%CE%B1%CF%81%CF%84%CE%B1/#prettyPhoto[1022]/0/

Zbor Fige. (2021, March 29). Zbor Fige – Dodolska [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tGYAJ-52FRk