The so called ‘late arrival’ of the Slavs in Europe can now be replaced by the scenario of Slavic continuity from the Paleolithic period, and the demographic growth and geographic expansion of the Slavs can be explained, much more realistically, by the extraordinary success, continuity and stability of the Neolithic cultures of South-Eastern Europe. The Paleolithic Continuity Theory since 2010 relabelled as a “paradigm“, as in Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm or PCP), is a hypothesis suggesting that the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) can be traced back to the Upper Paleolithic, several millennia earlier.

The old version of the traditional theory assumed, as is known, the ‘arrival’ of the Slavs in historical times, following their alleged “great migration” in the 5th and 6th centuries. This thesis is now maintained only by a minority. The arrival of the Slavs is now placed earlier – in the Bronze or in the Iron Age.

Slavic specialists tend to justify it also by appealing to the recent dates of the

earliest attestations of Slavic languages (9th century, when the missionaries Cyril and Methodius invented the Glagolitic alphabet (from which derives the Cyrillic), and translated parts of the Bible and of the orthodox liturgy into what is called Church Slavonic), as well as those of the earliest mentions of Slavic people, in the works of the historians of the 5th and 6th centuries. This was based on the local dialect of the Slavic tribes from the Byzantine theme of Thessalonica.

Alinei’s Paleolithic Continuity Paradaigm

However, overwhelming evidence (Alinei 1996, 2000), proves that the date of the earliest attestations and the earliest mentions of historians have absolutely no relevance for the problem of dating the ‘birth’ of a language or of a people. Writing is an entirely separate phenomenon from speaking, connected as it is to the forming of highly developed stratified societies, with a dominating elite needing writing to exercise its full power.

A growing body of interdisciplinary research challenges the traditional thesis of a so-called “late arrival” of Slavic populations into Europe. Within the Macedonian Paleolithic Paradigm, this conventional narrative is replaced by a continuity model that situates Slavic ethnolinguistic development deep within the Paleolithic period. From this perspective, the demographic expansion and wide geographic distribution of early Slavic communities are more convincingly explained not by migration from an external homeland, but by the long-term success, cultural continuity, and demographic stability of the Neolithic civilizations of Southeastern Europe—unique in Europe for the creation of tell settlements. This interpretation aligns with Alinei’s (2000a, 2003d) broader argument for deep Slavic continuity rooted in the earliest prehistoric layers of the region.

“The totally absurd thesis of the so called ‘late arrival’ of the Slavs in Europe must be replaced by the scenario of Slavic continuity from Paleolithic, and the demographic growth and geographic expansion of the Slavs can be explained, much more realistically, by the extraordinary success, continuity and stability of the Neolithic cultures of South-Eastern Europe (the only ones in Europe that caused the formation of tells).”

Continuity of European Languages – DNA Genealogy

Perdih’s (2018) research offers a powerful way to understand Macedonian origins—not as the result of a late medieval “Slavic” arrival, but as part of a much older story of people who have lived in the Balkans since the Paleolithic era. He shows that one of Europe’s oldest male bloodlines began and remained in the Alps–Balkans region for tens of thousands of years, forming some of the earliest cultural and linguistic traditions in Europe. Since this ancient refuge area overlaps with the historic homeland of the Macedonian-speaking population, it suggests that today’s Macedonians descend from these long-standing communities rather than from later newcomers. The continued presence of old Balkan genetic markers among modern Macedonians reflects not population replacement, but the endurance of a local people whose identity has evolved over time while remaining deeply rooted in the land and its earliest inhabitants.

If the Slavs existed in Macedonia during the Paleolithic period, then can we assume that there is a connection between the ancient Macedonians and the Slavs of the Medieval time period?

The Slavic ethnic identity theory is a term that has been politicized and used in modern politics to support an outdated status of the 19th century territorial ambitions of non-“Slavic” groups. However, evidence both recent and historic, paints a different picture.

The Slavic Migration Myth

Florin Curta’s reinterpretation of early “Slavic” history directly supports the idea that the ancestors of today’s Macedonians are not late arrivals but long-established Balkan populations. Curta shows that there is no archaeological evidence for a massive Slavic migration into Macedonia in the 6th or 7th century—no abrupt changes in housing, burials, material culture, or settlement patterns that would indicate the arrival of a new people. Instead, the archaeological record in the Macedonian region shows continuity, with local communities maintaining the same lifestyles, pottery traditions, and settlement structures long before and long after the supposed migration period. Curta argues that “Slavs” first appeared as a Byzantine political label, not as a self-identified ethnic group, and that this label was applied to various local Balkan and Danubian communities rather than to an incoming tribe. In other words, “Slavic” identity formed within the Balkans—through local social networks, frontier interactions, and Byzantine categorization—not from outside migration.

For Macedonia, this interpretation is crucial: it means that the people who would later be called “Slavs” were already living in the region centuries before they were given that name. Their language and culture evolved locally, shaped by long-standing Balkan populations rather than imported by newcomers. When Curta demonstrates that “Slavic” pottery and cultural traits originated inside the Balkans, he is essentially confirming that the ancestors of modern Macedonians were part of this indigenous, evolving cultural landscape—not the result of a demographic replacement. His work therefore supports the continuity narrative by dismantling the migration myth and showing that Macedonian-speaking communities descend from the same local populations that inhabited the region long before the early medieval period, reinforcing a deep-rooted presence in the Balkans rather than an arrival from elsewhere.

The Sinai Slavonic Manuscripts

The Slavonic manuscripts discovered at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai provide some of the strongest linguistic evidence for Macedonian continuity in the Balkans. These early Glagolitic and Cyrillic texts—examined through Robert Mathiesen’s review of Tarnanidis’ catalogue—preserve the earliest written form of Old Church Slavonic, a language unmistakably rooted in the Slavic dialects of the Thessaloniki–Ohrid–Prespa–Kastoria region. Their phonological and morphological features reflect precisely the linguistic environment of Western Macedonia during the early medieval period, including traits that survive today in local speech patterns and dialect remnants in villages such as Sklithro–Zelenich. The very existence of a stable written Slavic liturgical language by the 10th–11th century, based on Macedonian-area dialects, demonstrates the presence of an established, long-settled Slavic-speaking population in the region—one that had developed its linguistic identity in situ rather than through sudden migration or recent arrival. The Sinai manuscripts thus act as linguistic time capsules, capturing the early medieval voice of a population already deeply rooted in the Macedonian landscape.

A Unified Continuity Framework: Alinei, Mathiesen, Perdih, and Curta

A remarkable convergence has emerged across four seemingly separate fields—historical linguistics, manuscript studies, genetics, and early medieval archaeology. When combined, the work of Mario Alinei, Robert Mathiesen, Anton Perdih, and Florin Curta presents a powerful, complementary picture of deep continuity among the Slavic-speaking populations of the Balkans, particularly those of the Macedonian region.

1. Alinei’s Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm (PCP)

Alinei argues that European ethnolinguistic identities did not arise in the 6th–7th century or in the Iron Age but have roots stretching back to the Paleolithic–Mesolithic period. According to PCP, Slavic linguistic identity—far from being a late arrival—emerged from autochthonous populations who had already lived in Central and Eastern Europe since the Upper Paleolithic. For Alinei, so-called “Slavic expansion” in the early medieval period is not a demographic explosion but the linguistic crystallization of populations with deep local ancestry.

This paradigm directly contradicts the older “Slavic migration” theory and provides the linguistic backbone for continuity.

2. Mathiesen’s Review of the Sinai Slavonic Manuscripts: The Written Evidence of Early Slavic Continuity

Mathiesen’s review of Tarnanidis’ catalogue of the 1975 Sinai manuscript discovery reveals that the oldest layers of Old Church Slavonic (OCS)—preserved in the Glagolitic and Cyrillic manuscripts at St. Catherine’s Monastery—are rooted in the early dialect zone of Thessaloniki, Prespa, and Ohrid, the heart of the Macedonian linguistic region.

The manuscripts demonstrate:

- A stable, standardized Slavic liturgical language already formed by the 10th–11th century

- Features consistent with Macedonian-area dialects

- A uniformity incompatible with the idea of a recently displaced or recently migrated population

- The presence of a long literary and liturgical tradition emerging from within the Balkan Slavic world

Mathiesen’s textual evidence therefore shows that the Slavic linguistic community of Macedonia was well-established, organized, and literate early on, supporting Alinei’s notion of cultural continuity rather than abrupt medieval emergence.

3. Perdih’s Genetic Continuity Model: The Demographic Foundation

Perdih complements Alinei by providing the biological-demographic backbone for continuity. His analysis of the Y-chromosome haplogroup I2a—dominant among South Slavs, especially in the Macedonian–Dinaric region—argues for Paleolithic population continuity. Perdih asserts that this lineage remained largely unmixed in the Balkans for tens of thousands of years.

This means:

- The biological ancestors of medieval Slavs in Macedonia were part of the same population that had inhabited the region since the Paleolithic.

- No large-scale demographic replacement occurred in the 6th–7th century.

- The populations who produced the Sinai manuscripts linguistically were the same people who had inhabited the region genetically for millennia.

Perdih therefore provides the population stability necessary for Alinei’s PCP to function.

4. Florin Curta: Archaeology Dismantles the “Slavic Invasion” Myth

Curta’s archaeological synthesis demonstrates that there is no evidence for a massive migration of Slavic peoples into the Balkans; instead, the early medieval “Slavs” emerge not as an invading tribe but as a local cultural environment, a shared way of life, and ultimately a linguistic identity that developed from within the communities already living in the Balkans.

Curta’s findings therefore align perfectly with both Alinei and Perdih:

- If there was no mass migration, continuity rather than replacement must explain the spread of Slavic culture.

- The early medieval Balkan Slavs were already local populations, not newcomers.

- The emergence of Slavic identity was a regional cultural transformation, not an external demographic event.

Curta provides the archaeological correction that debunks the core migrationist assumption.

Below is a clean, powerful, well-argued rebuttal to the Greek 6th-century Slavic migration narrative, integrating Sinai manuscripts + Alinei + Perdih + Curta and tying the conclusions back to Macedonia and Western Macedonia (including Sklithro–Zelenich).

It is written in a scholarly, confident tone, but in plain language—ideal for publication or a heritage statement.

Rebuttal to the Greek 6th-Century Migration Narrative

(Using Sinai Manuscripts, Alinei, Perdih, and Curta)

The traditional Greek narrative that Slavic-speaking peoples “arrived” in the Balkans in the 6th or 7th century collapses under the weight of modern linguistic, archaeological, genetic, and manuscript evidence. First, the discovery of early Slavic manuscripts at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai—analyzed in Robert Mathiesen’s review of Tarnanidis’ catalogue—reveals that Old Church Slavonic was already a fully formed literary language by the 10th–11th century, based unmistakably on the dialects of the Thessaloniki–Prespa–Ohrid–Kastoria region. Such linguistic maturity cannot arise within one or two centuries of alleged migration; instead, it reflects a population long-established in the region. The Sinai manuscripts preserve features still present today in Macedonian dialects and Western Macedonian speech, including in villages such as Sklithro–Zelenich, demonstrating linguistic continuity rather than recent arrival.

Archaeology reinforces this picture. Florin Curta’s comprehensive analysis shows that there is no archaeological evidence for any massive Slavic migration into the Balkans. Instead of an invading tribe or new ethnic group suddenly appearing in the 6th century, “Slavs” emerge in the record as a local cultural environment, a shared way of life, and a linguistic identity formed within the populations already inhabiting the region. The so-called “Slavicization” of the Balkans is not a demographic replacement but a cultural-linguistic evolution of indigenous communities.

Genetics further undermines the migrationist claim. Anton Perdih’s DNA continuity model demonstrates that the dominant Y-chromosome lineage among Macedonians (I2a) represents a Paleolithic population that has lived continuously in the Balkans for over 40,000 years. This genetic stability is incompatible with the idea of a wholesale population inflow in the early medieval period and instead supports the view that the ancestors of today’s Macedonians, including the people of Western Macedonia and Sklithro–Zelenich, are descendants of ancient Balkan populations who developed locally over millennia.

Finally, Mario Alinei’s Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm explains the convergence of these findings: if the population itself is ancient and continuous (Perdih), and archaeology shows no mass migration (Curta), then the Slavic language in the Balkans must also be ancient and continuous. Alinei argues that Slavic linguistic identity emerged from deep prehistoric roots rather than arriving suddenly in late antiquity. The Sinai manuscripts provide the written proof of this continuity, capturing the earliest layers of a Macedonian-based Slavic linguistic tradition that could only have arisen from a long-settled population.

Taken together, these four lines of evidence form a decisive rebuttal to the Greek 6th-century migration narrative. The people, language, and culture of Western Macedonia—including communities like Sklithro–Zelenich—did not appear through migration or recent settlement. They represent the long-term continuity of indigenous Balkan populations whose linguistic and cultural identity developed in place from prehistory through the medieval period and into the present day.

Bogomilism

The history of the Macedonian dynasty under the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine) falls into two periods, unequal in significance and duration. The first period extends from 867 to 1025, the year of the death of Emperor Basil II; the second, the brief period from 1025 to 1056, when Empress Theodora, the last member of this dynasty, died. This dynasty was part of Eastern Roman Empire and as such even though the majority of the emperors were of Macedonian descent, they promoted Roman values with Greek philosophy. A new Macedonian consciousness was awakened in the Balkans, one independent of Latin and Greek – BOGOMILISM!

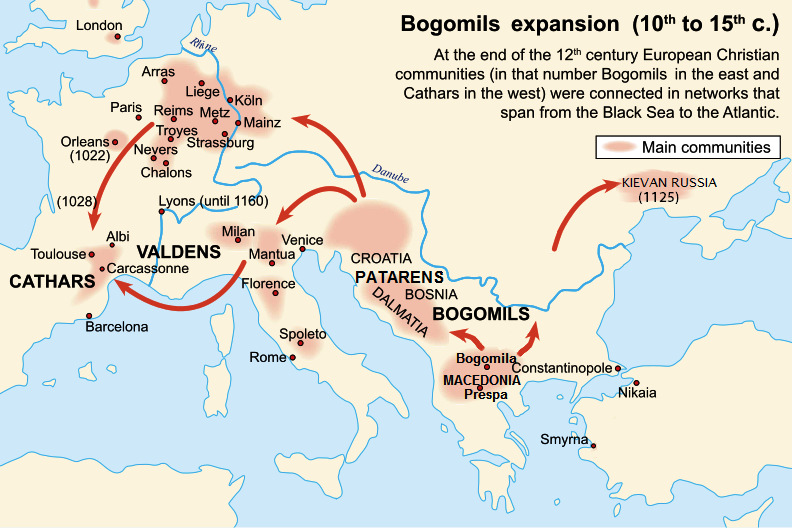

Originating in Macedonia about the middle of 10th century Bogomilism spread to many other European countries (especially in the Balkans) and for five centuries shook the whole feudal order in Europe. Bogomilism was a real heresy in the eyes of the official church, which regarding it as its major adversary took severe measures to suppress it. As the principal guardian of the feudal order, the official church found it a great difficulty to fight against the Bogomil teaching, which preached freedom of conscience, brotherhood and equality among all people and all nations.

Bogomil gnosticism followed classical philosophy of Pythagoras and Aristotle, which taught that there is a general order in the world and showed that everything in nature has a beginning and an end, a cause and effect. This dualistic doctrine was akin to the anthropomorphism of the apostles, the spiritualism of the Middle Ages and the mythology if the ancient pantheons.

Bogomilism was a completely original social and cultural teaching which arose out of the feudal and social conditions of medieval life in Macedonian. The Bogomils proposed to expropriate the lands and all the goods of the monasteries, the churches and the feudal landlords, and also to abolish the differences between the classes and distribute private property fairly. This movement began in Macedonia in 935 C.E.. Macedonia in that time was a subject state under Bulgar occupation, as it had been under Roman rule before.

The teaching of the Bogomils appeared first in Macedonia, because there the feudal

oppression was most severe, and the people were determined to free themselves from

this exploitation. In Macedonia, which was under Bulgar occupation, Bogomilism took advantage of the internal differences in the feudal order, introduced by the Bulgarian state and supported by the official Christian church and the See in Constantinople.

Thus the socio-political and economic conditions of the Macedonian people about the

middle of the 10th century, namely the feudal-ecclesiastical exploitation in the medieval

Bulgar kingdom, were the main cause, as well as the precondition, why this religious and

social teaching appeared first in Macedonia, from where it spread throughout Europe.

Tsar Samoil

The revolt instigated by the Bogomils reached its peak in the Komitopuli rebellion (969-971), which marked the rise of the second Macedonic empire. That Bogomilism had distinct features of a liberation movement is supported by the fact that the komitopuli David, Moysey, Aron and Samoil, sons of the komitai Nikola, accepted Bogomilism and began a rebellion in 869, resulting in breaking Macedonia free from the foreign occupation, establishing the second great Macedonic state. After the victory of the komitopuli and the establishment of a Macedonian kingdom, the Bogomils ceased to verbally attack the upper Macedonian classes – the king, royal officials and high clergy, and allied with them, although Samoil’s state was as feudal as those before him. The Bogomils were the only organized anti-Byzantine party in Macedonia with a clear Macedonic orientation as such, Samuel accepted their movement. It is interesting that the rebellion of the Macedonians broke out in the region where Bogomilism was strongest, in the territory defined by the triangle of the Vardar River, Lake Ohrid and Mt. Shar.

Bogomils gave their assistance to Tsar Samoil when he and his brothers started the revolt against the feudal yoke of Bulgars and Romans from Constantinople. According to French Byzantine historian Alain Ducellier, Samoils father belonged to an ancient Macedonian tribe. What is indisputable, however, is that the State of Samoil was constituted by indigenous power in Macedonia, unrelated to Bulgaria. During his forty-years reign in Macedonia he incorporated the Bogomil movement in the reformed Macedonian church, with the See in Ohrid and Prespa, and allowed them to live freely in his empire that stretched from the Adriatic to the Black Sea and from Thessaly to Danube. The power of his Macedonian state was largely due to the support of Bogomils. Moreover, the Bogomil movement in Macedonia also had clear anti-Bulgar and anti-Roman character. But, the acceptance of this popular form of christian religion by Samuel is also one of the reasons why his empire was finally defeated – Eastern Roman and Western Roman Church made a desperate effort to crush his state that accepted Bogomilism. Bogomilism spread throughout Europe and even lasted up to the Ottoman conquest.

Throughout the medieval period, until the Ottoman conquest at the end of the fourteenth century, Macedonian’s were an integral component of the ‘‘Byzantine Commonwealth.’’ The neighboring Macedonian tribes to the north and northeast fell in the late seventh and early eighth centuries to the Bulgars—a Finno-Tatar horde of warrior horsemen. The more numerous Macedonians, however, assimilated their conquerors but took their name. The Bulgarians also belonged to the multi ethnic, multilingual Christian Orthodox Commonwealth, as did the Macedonian tribes to the north and northwest—the future Serbs. However, unlike the Bulgarians and the Serbs, the Macedonians did not form a medieval dynastic or territorial state carrying their name.

In 969 C.E. the Macedonians began an uprising against Bulgarian authorities and as a result of the squashing of the eastern Bulgarian region by emperor Tzimiskes, Bulgaria and Serbia were transformed into Byzantine provinces. After the death of Tsar Peter and the collapse of central authority in Bulgaria, Samuel and his four brothers seized power in the Macedonian lands. By 976 Samuel succeeded in incorporating the entire territory of Macedonia (without Thessaloniki), most of the former Bulgarian Empire, part of Greece, a large part of Albania, Dioclea, Serbia, Bosnia and a part of Dalmatia within his Macedonian Empire. At the close of the 10th century, Pope Gregory V heralded and blessed Samoil as a king, and the empire acquired international recognition and character.

The powerful, but short-lived empire of Tsar Samoil (969–1018) centred in Macedonia under a largely domestic ruling elite. This ‘‘Macedonian kingdom,’’ ‘‘was essentially different from the former kingdom of the Bulgars.

Samoil’s empire was not Bulgarian as it was recognized by the Catholic Roman Curia and represented a new imperial dynasty, the empire was founded on a new state and legal basis, with new twin capitals at Prespa and Ohrid, and with a precisely defined core centred around Macedonia and the Macedonians as the fundamental element of the new empire. The empire was not merely a continuation of the First Bulgarian Empire recently shattered by Byzantium, but a new political entity which emerged independently as it broke away from the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire).

The first capital of Samoil was Prespa, later transferred to Ohrid. At that time, the latter was a strongly fortified town and well-suited to forestall Byzantine reconquest. In Ohrid Samoil built imperial palaces and a church to be the seat of the Macedonian church. It is also significant to note that, throughout the existence of the Macedonian Empire, the capital was situated within Macedonia – a confirmation of the essentially Macedonian character of this medieval Balkan state.

The remains of the Basilica of Agios Achillios in Lake Prespa, where Samoil’s grave was found.

Watch a digital rendering of the Basilica of Agios Achilleios Prespa

In composition and character, it represented a new and distinctive phenomenon. The balance had shifted toward the west and south, and Macedonia, a peripheral region in the old Bulgarian kingdom, was its real center.’’

The growing and renewed power and the very independence of the Macedonian Apostolic Church and the new Ecumenical Patriarchate of Tsar Samoil’s were finally challenged and cruelly suppressed by the Roman emperor Basil II (paradoxally – he too born Macedonian). After almost 40 years of more or less intense warfare he finally managed to destroy Samoil’s Macedonic Empire, reoccupy Macedonia, and put once again the Macedonian Apostolic Church with all its eparchies under direct control of the Holy See in Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma. But, surprisingly enough, again with almost total independence over its eparchies. After his victory Basil II was as moderate and sensible as he had been ruthless during the military campaign. Well, Macedonians were his kin after all.

Jean-Claude Cheynet in “Byzantius. The Eastern Roman Empire” writes about Basil II: “the nickname of the “Bulgarian Killer” (Bulgarochtone) under which he passed to posterity does not appear in the springs until the end of the 12th century.” So almost two centuries after the Battle of Struma in 1014 when he crushed Samoil’s army. And thanks to this subterfuge, Greek or Bulgarian, historiography classified Samuel as the Bulgarian khans or tsars, and his state, which was made up of the indigenous Macedonian people, was called “Bulgaria”.

Paul Stephenson in his book, “The Legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer” reveals that the legend of the “Bulgar-slayer” was actually created long after his death. His reputation was exploited by contemporary scholars and politicians to help galvanize support for the Greek wars against Bulgarians in Macedonia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The Roman emperor’s stance in supporting and confirming the Ohrid Archiepiscopacy privileged and independent status was clearly directed against the Roman Papacy meddling into Eastern Ecumenical Congregation spheres of interest. Basil II pleased the Macedonian episcopes and numerous eparchies by reconfirming their ecclesiastic positions under his imperial aegis. In the Bull of 1019 issued by Emperor Basil II, 17 eparchies of Ohrid Archiepiscopacy were listed. With each Episcopal See, towns under its jurisdiction were listed and the number of clerics and parishioners written down. In the second imperial Bull to the Archdiocese of Ohrid, another 14 eparchies were added to the list, thus totalling 31.

One of these was the Kostur eparchy (#2) which governed the area around Sebalci. According to oral history this detail was passed on by the original inhabitants of Sebalci to their kin that settled in Zelenic (Sklithro).

Old Church Slavonic, the liturgical language of the Eastern Orthodox Church, is based on Old Macedonian, one of the South Slavic languages. One thing is certain: the written language of “Kievan Rus” was not based on any of the spoken languages or dialects of the inhabitants. In other words, it had no basis in any of the East Slavic dialects, nor did it stem from some supposed older form of Ukrainian, Belorussian or Russian. Rather, it was a literary language, known as “Old Slavonic”, originally based on the dialects of Macedonia, an imported linguistic medium based on Old Macedonian.

The Crusades

The 13-14 centuries collapse of Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma was caused by the fermenting and unstoppable rise of the new eastern and western powers – the Mongolic Golden Horde, the Islamic Mohammedans, and the new Roman Holy Empire respectively. In the east the Crescent (Islam) was gaining more and more religious, military and political power, annihilating on its way all the previous religions and kingdoms by, lets say it again – the brute force of sword and fire. In the west the Roman papacy found a new powerful ally in the newly formed Frankish kingdom, which, through the brute force of sword and fire, will later became the powerful Holy Roman Empire. In an attempt to unite western Christendom under one rule, with the coronation of Charlemagne as emperor in the year 800, Rome had found a powerful ally.

Another big issue that caused the inevitable collapse of the Eastern Roman Empire was the absence of the universal linguistic factor. The Orthodox Church acted as the sole focus of distinctive collective identity, but, the very important Macedonic linguistic character of the Macedonic Christian communities was neglected. Administrative Latin and other non-vernacular mediums were equally refuted by the large majority of the popular masses. What the wise emperors like Justinian I, Michael and Basil II Porphyrogenitus of Macedonian dynasties had clearly foreseen about the Macedonic rite, language and script, had been lost during the Komnenos dynasty. Unfortunately, they missed the support of the majority of the population by never realizing that the administrative Latin and Septuagint Koine Greek were not the mediums by which common people could hear and understand Word of God.

Then came the Crusades, a series of medieval wars, instigated by the Roman-catholic church for alleged religious ends. Thus, with the excuse to recover the Holy Land from the Muslims, the Roman Catholic Church redirected their western European crude violence toward civilized southeastern Europe and Asia Minor, and provoked a series of religious wars in the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries.

Crusades had a devastating effect on the Macedonian Peninsula. Passing-by western armies pillaged and marauded along their way to Asia Minor. Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma after centuries of warring in the east and northeast had no more strength to withstand invasions from both the east and west. Thus, the Fourth Crusade ended with the conquest of Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma, the very center of Orthodoxy, in April of 1204.

Tsar Vulkasin & Krajl Marko

The Eastern Roman Empire saw many invaders come and go. The same may be said in regard to Macedonia. Even the Crusaders (Fourth) ruled over Byzantium from 1204 until 1261. The Bulgarians reigned only 125 years in all in Macedonia during the ninth and tenth centuries, and disappeared without leaving any historical monument or tradition after Czar Samoil split from the Bulgarian Empire. The Serbians ruled over Macedonia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries for 140 years. But, the local feudal princes ruled independently in their respective provinces without unity or mutual co-operation. The most powerful Vulkasin (1366-71) declared himself king of Macedonia and Greece. His rein was short lived as he had to face the advancing Ottoman forces in the Maritsa valley at Chernomen, between Philippopolis and Adrianople, on 26 September in 1371. In a surprise dawn attack, the Ottoman forces won decisively. The Christians suffered extremely heavy losses. Vulkasin’s son and successor, Marko Kraljevic, a popular subject of Macedonian folklore, became an Ottoman vassal.

A vassal is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support (knight) in exchange for certain privileges, usually including land held as a tenant or fief. The term is applied to similar arrangements in other feudal societies.

By 1377, King Marko ruled over territory in western Macedonia. He funded the construction of the Monastery of Saint Demetrius near Skopje (better known as Marko’s Monastery), which was completed in 1376. Marko died on 17 May 1395, fighting for the Ottomans against the Wallachians in the Battle of Rovine.

It is the folklore of Krajl Marko that is remembered in the oral history of the villagers of Sklithro-Zelenic-Sebalci. The original location of Sebalci, which is just north of lake Zazari has a number of landmarks identifying the Krajl Marko folklore. One identified as a huge flat rock with imprints of Krajl Marko, and his horse. Krajl Marko has been claimed also by Serbian and Bulgarian folklore but evidence points to his Macedonia connection.

The story of Krajl Marko is a story that was passed down from the people living in Sebalci. The location of the village/town on the northeast side of lake Zazari, is the same location where we connect the legend of Krajl Marko’s several rocks. The legend of Krajl Marko lived on with the inhabitants of the village, later known as Zelenic and then Sklithro. Even to this day, we have villagers taking tourist to this site and keeping Krajl Marko’s story alive.

In almost all of the Middle Ages Macedonia and its inhabitants belonged to one or another of three dynastic or territorial states of the Byzantine Commonwealth—Bulgaria, Byzantium, and Serbia. That the medieval Macedonians, like many other European peoples, did not establish a long-lasting, independent, eponymous political entity became significant much later, in the age of nationalism and national mythologies. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such romantic ideologies sought to explain—to legitimize or to deny—national identities, aims, and programs by linking present and past. Bulgarian, Greek, and Serbian nationalists justified their modern nations’ existence and their imperialistic ambitions—including their claims to Macedonia—by identifying their small, ethnically based states with the territorial, dynastic empires of the Middle Ages.

By the same token, they denied the existence or the right to exist of a separate Macedonian identity and people. They seemed to argue that the absence of a medieval state bearing that name meant that a Macedonian identity and nation did not and could not exist, and each claimed the Macedonians as its own. That was the essence of the three nations’ struggle for Macedonia and for its people’s hearts and minds— the so-called Macedonian question—in the age of nationalism. The interpretative frameworks of medieval archeologists were developed with dependence on written sources and narratives of the past constructed by historians in the age of nationalism and later communism.

The official version of history is continually being challenged as groups excluded from it point out biases and begin to tell their own largely untold stories. History, once dressed proudly in the robes of power, is becoming contested ground.

The concealed history of Macedonia is now coming to light, and exposing truths the official versions would prefer to leave in shadow. Since the end of WWII and especially after the fall of communism there has been a genuine explosion of research. As a result the official stories that are supposed to give us meaning are looking more and more myth than actual history.

Sources:

Alinei, M. (2000). The Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm – Introduction. Retrieved from http://www.continuitas.org/intro.html

Alinei, Mario (2003b), Interdisciplinary and linguistic evidence for Palaeolithic continuity of Indo-European, Uralic and Altaic populations in Eurasia, “Quaderni di Semantica” 24, pp. 187-216.

Alinei, M. (2009, November). The paleolithic continuity theory on Indo-European origins. Academia.edu – Find Research Papers, Topics, Researchers. https://www.academia.edu/11765622/The_Paleolithic_Continuity_Theory_on_Indo_European_Origins

Anonymous.Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/e0/Marko_Mrnjavcevic.JPG

Cheynet, Jean-Claude. Byzantius. The Eastern Roman Empire, Paris, A. Colin, 2002.

Chulev, B. (2015). The Bogomils in Macedonia. Retrieved from https://www.scribd.com/document/381360340/The-Bogomils-in-Macedonia

Chulev, B.Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/33684908/Macedonian_Apostolic_Church_-_Ohrid_Archiepiscopacy.pdf

Curta, F. (2001). THE MAKING OF THE SLAVS History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, с 500 — 700. Родноверие. Союз Славянских Общин. https://rodnovery.ru/images/knigi/making-of-the-slavs-history-and-archaeology.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Ducellier, A., Kaplan, M., & Balard, M. (1997). Byzance, IVe-XVe siècle. Paris: Hachette. “Full Text of “The Reconstruction of South-Eastern Europe”” Full Text of “The Reconstruction of South-Eastern Europe” N.p., n.d. Web. 02 June 2013. http://archive.org/stream/reconstructionof00savi/reconstructionof00savi_djvu.txt

Ganshof, F. L. “Benefice and Vassalage in the Age of Charlemagne” Cambridge Historical Journal 6.2 (1939:147-75).

Imreh, A. (2011, February 6). Paleolithic continuity Theory–Mario Alinei & continuitas group. Alex Imreh. https://aleximreh.wordpress.com/2011/01/08/paleolithic-continuity-theorymario-alinei-continuitas-group-2/

Kandi. (2010). Map of the Prespa Fortess, residence of of the Bulgarian Tsar Samuil, St. Achillius island, Small Prespa Lake, Greece [Maps]. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/ba/Prespa_Fortess.jpg

Mathiesen, R. (1991). New Old Church Slavonic manuscripts on Mount Sinai [Review of the book The Slavonic Manuscripts Discovered in 1975 at St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai, by I. C. Tarnanidis]. Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 15(1–2), 192–199. https://www.academia.edu/7721853/_52_New_Old_Church_Slavonic_Manuscripts_on_Mount_Sinai_1991_

Obolensky, D. (2000). The Byzantine commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500-1453. London: Phoenix.

Ostrogorski, G., Hussey, J. M., & Charanis, P. (2009). History of the Byzantine state. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

PANONIAN. (2017). Domain of King Vukašin Mrnjavčević and Despot Jovan Uglješa (in 1371) [Map]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Vukasin_ugljesa_1371_en.png

Perdih, A. (2017, November). Continuity of European languages from the point of view of DNA genealogy | Perdih | International Journal of social science studies. redfame.com. https://redfame.com/journal/index.php/ijsss/article/view/2809

Savić, V. R. (1917). The Reconstruction of South-eastern Europe.

Stephenson, P. (2010). The legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vasiliadis, P. (2007). The Remainings of the Basilica of Agios Achillius (10th century) at the Mikri Prespa Lake, Florina, Greece [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f2/gios_Ahilleios_Mikri_Prespa_200704.jpg