Historical and Cultural Origins of the Lazarines

Pagan Roots: Echoes of Ancient Spring Rites

Long before Christianity arrived in the Macedonian lands, the Lazarines ritual was rooted in ancient pagan traditions tied to the natural cycles of life, fertility, and the renewal of the earth. Celebrated each spring, this custom marked the changing of seasons and the reawakening of nature after winter’s long sleep.

It was especially important in agrarian communities, where the success of crops and livestock meant survival. The Lazarinki—young girls at the threshold of womanhood—took part in symbolic processions representing fertility, growth, and the hope for abundance. The rituals served as a kind of initiation into adulthood, linking them to the earth’s rhythms and the social responsibilities of womanhood.

Many of the elements seen in today’s Lazarines—flowers, songs, circular dances (oros), and house blessings—carry symbolic meaning from these early beliefs, celebrating not only agricultural fertility but also the blossoming of the girls themselves.

Christian Layering: The Resurrection of Lazarus and Renewal

With the spread of Christianity in the Balkans, the existing ritual was absorbed into the Christian calendar and came to be celebrated on Lazarus Saturday, the day before Palm Sunday. This day commemorates the miracle of Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead, a story rich in themes of rebirth, transformation, and the promise of life after death.

Rather than erasing the older tradition, the Church infused it with Christian meaning, allowing it to continue under a new banner. The rebirth of nature was now spiritually mirrored by the resurrection of Lazarus. This dual symbolism gave the Lazarines even deeper significance—connecting earthly and spiritual renewal, both in the land and in the human soul.

Even today, many Lazarinki carry willow branches or spring blossoms, which in Orthodox symbolism represent eternal life and joy.

Macedonian Tradition: A Shared Custom with a Macedonian Heart

The Lazarines ritual is part of a wider South Slavic cultural landscape, with variations found across Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, and parts of northern Greece. While the general structure is shared—groups of girls visiting homes, singing blessings, and receiving gifts—the Macedonian tradition is uniquely rich in local colour, song, and meaning.

In Macedonian villages like Zelenich, the songs are performed in local dialects, preserving rare poetic forms and words. The dances are often accompanied by traditional instruments like the zurla and tapan, and the costumes reflect the intricate embroidery and patterns unique to each village.

These regional expressions reflect centuries of cultural layering, oral transmission, and community memory, making the Lazarines not just a ritual—but a living archive of Macedonian identity, resilience, and beauty.

Participants and Ritual: The Heart of the Lazarines Tradition

Who Takes Part?

At the centre of the Lazarines custom are the Lazarinki (or Lazarki), a group of unmarried village girls, usually between the ages of 10 and 16. These girls are chosen not for their performance skills, but for their youth, purity, and communal spirit. They represent the renewal of life, both in nature and in society, and serve as living links between generations, entrusted with preserving and carrying forward ancestral tradition.

Historically, participating as a Lazarinka was a significant cultural moment in a girl’s life—a rite of passage signalling her coming-of-age and symbolic readiness for the adult roles of family, marriage, and motherhood. In small communities, girls often eagerly awaited the age when they could finally take part, and families proudly supported them, helping them dress and prepare.

Traditional Dress: Beauty with Symbolism

On the morning of Lazarus Saturday, the Lazarinki gather in full traditional Macedonian costume, often prepared weeks in advance or passed down through generations. Each piece of their clothing is symbolically charged and deeply rooted in local customs:

- White linen blouses – representing purity, youth, and spiritual cleanliness.

- Hand-embroidered aprons – woven with geometric patterns or floral motifs specific to their village, often made by mothers or grandmothers.

- Floral headbands or wreaths – made of real or silk flowers, worn on their heads as symbols of spring, fertility, and beauty.

- Red woven sashes (појас) – wrapped around the waist to symbolize vital energy and protection.

- Decorative coins or jewellery – in some villages, girls wear strings of gold or silver coins, pinned to their blouses or headscarves, reflecting family prosperity, luck, and status.

Some costumes include small lacework, silver crosses, or traditional slippers (опинци), completing the full ceremonial appearance. When walking through the village in unison, the Lazarinki evoke a powerful image of grace, tradition, and renewal.

Preparation: A Ritual in Itself

Participation in the Lazarines is not spontaneous—it is the result of dedicated preparation that often begins several weeks before the event. The girls meet regularly in small groups, usually in someone’s home, to learn and rehearse the traditional songs, dance steps, and ritual greetings.

This preparation period is just as important as the public procession. It is a time when younger girls learn from older ones, and when village elders—especially grandmothers—step in as guardians of oral tradition. They teach the girls songs sung in local Macedonian dialects, share the meanings behind them, and guide them on the proper way to bless a household or enter a home with dignity and grace.

They also plan the route the girls will take—house by house, from one end of the village to the other—ensuring that no home is left out of the blessings.

During this time, the girls also bond with one another, forming friendships and a collective sense of purpose. It is an experience of cultural learning, female solidarity, and inter-generational transmission that lives on long after the festival ends.

Ritual Activities: Songs, Blessings, and the Dance of Spring

Once prepared and dressed in their ceremonial attire, the Lazarinki begin the most vibrant and meaningful part of the custom—the ritual itself. This is not just a celebration, but a living performance of cultural memory, a spiritual and communal act that connects the participants with their ancestors, their land, and each other.

The ritual unfolds in several parts, each rich in symbolism, emotion, and age-old meaning.

A. House-to-House Procession: Walking the Village with Blessings

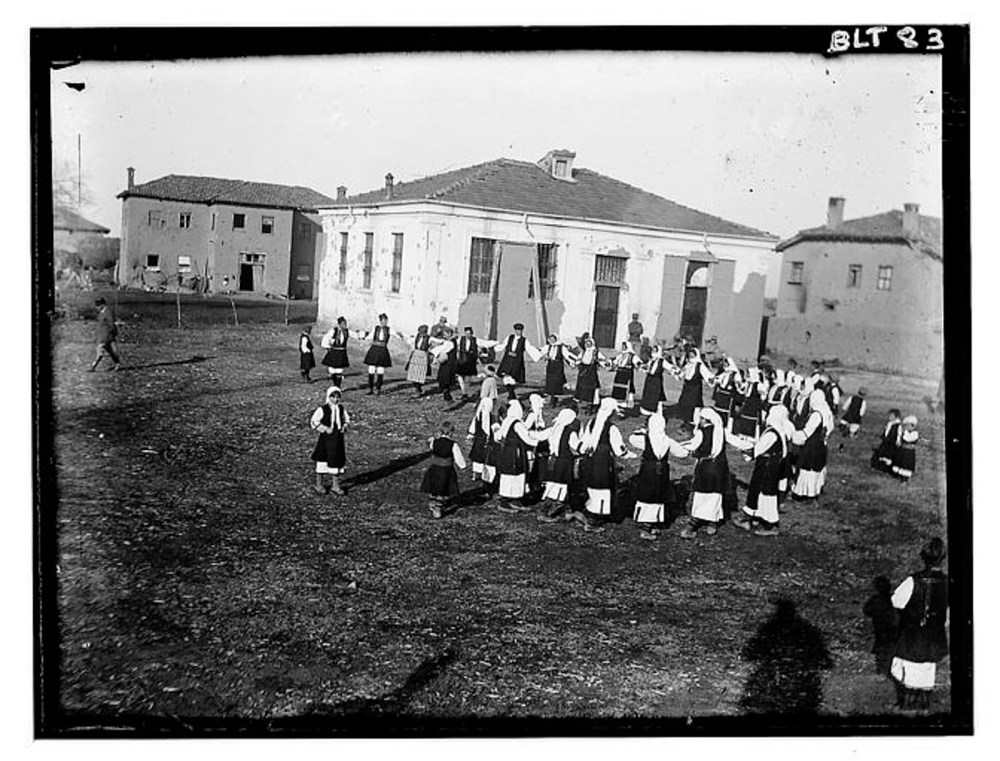

The ritual begins with the Lazarinki forming small groups—sometimes four or six girls—and setting out through the village. They move from house to house, stopping at each doorstep to sing ritual songs and perform gentle, symbolic dances (oros).

Their entrance is formal, reverent, and joyful. At each home, the girls stand in formation—sometimes in a half-circle—and begin to sing verses specific to the family or the occasion. These songs are carefully chosen and passed down orally, often praising the household’s health, prosperity, or fertility.

In return for their blessings, the girls are gifted with painted eggs, coins, sweets, and sometimes small gifts or baked bread. These gifts are not simply compensation—they are a reciprocal gesture of goodwill, reinforcing the bond between the community and its youth.

The procession continues for hours, with the girls stopping at every household in the village. By the end of the day, their baskets are filled with offerings, and the village is filled with the echo of ancient songs and laughter.

B. Lazarine Songs: Carriers of Hope, Memory, and Fertility

The songs are at the core of the ritual. Sung in the Macedonian language—often in village-specific dialects—they preserve poetic forms that are centuries old. They are filled with metaphor and blessings, invoking the health of the family, the fertility of the land, and the good fortune of the household.

Typical themes include:

- Wishes for a bountiful harvest

- Blessings for newlyweds or young men of marriageable age

- Praise for hospitality, wealth, or generosity

- Requests for protection from illness or bad fortune

Some songs are playful, some are deeply spiritual, and others are subtly instructive, reminding listeners of values like kindness, faith, and respect for elders. The repetition of lyrics and their melodic flow make them easy to remember and emotionally resonant, allowing even the youngest girls to carry them forward into the next generation.

C. Symbolism: Life, Growth, and the Transition to Womanhood

Every action in the Lazarines ritual carries deep symbolic meaning. The journey of the girls through the village is itself a procession of life and light, spreading renewal as they move from one home to the next.

Some of the most important symbolic elements include:

- Eggs: Representing fertility, new life, and the rebirth of spring. Painted eggs given to the girls symbolize the household’s desire for continuity and blessing.

- Flowers and Greenery: The wreaths worn by the girls and the branches they carry are ancient symbols of growth, nature’s abundance, and divine favour.

- Circle Dances (Oros): The circular pattern of the dances represents eternity, unity, and the cycle of seasons.

- The Girls Themselves: As they transition from childhood to maidenhood, their participation in the ritual mirrors the transformation of nature from dormancy to full bloom.

In earlier generations, a girl’s participation in Lazarines could signal her readiness for courtship or marriage, adding another layer of meaning to her role in the ritual.

Lazarića – A Special Time in Zelenich

The weekend before Orthodox Easter was a special time in Zelenich and other parts of Macedonia. This time was associated with the height of spring and all the hope and love that come with it, Lazarus Saturday (Lazarića) and Palm Sunday (Ćvetnići) are a lot more than religious holidays!

This day had been surrounded by our people with beautiful customs. One week before groups of girls would gather with their friends at chosen homes and make baked goods and practice singing traditional songs. Their main feature is dancing and singing without any participation of musical instruments. For the girls who decided to sing and dance the Lazarus songs, their preparation lasted throughout Lent . First of all, they had to find their match, or form their company, and then learn the songs and dances, but also prepare their costume.

When they found their match (group of girls), they made a mutual promise that they would not spoil their agreement. This mutual promise was given in the house of one of the girls where they prepared a “zelnic” (pie) and in front of it they gave their mutual promise. At first they stood on their knees in front of the zelnic pan and sang a Lazarus song.

Of the songs sung by the local Lazarki (Lazarines), little was said about Lazarus . Almost all of them were songs that referred to various life events, such as love, housekeeping, exile and others. But most of them were love songs. And the Lazarki, knowing the family situation of each house, found, sang and danced the song that best suited each house. It has been noted that in other parts of Macedonia, of the Lazarian songs brought by the refugees of 1922, only a few had reference to the resurrection of Lazarus.

On the eve of the feast, the girls went into the fields outside the village to collect flowers with which they would decorate their basket the next day dressed in local Macedonian costumes. The following week, on the Saturday, they would go house to house singing songs and dancing in the yards of the homes they would visit. Their reward would be a baked bun, egg and sometimes money for their performance.

These songs were “good luck” songs for the owner, their family, livestock and a good harvest. The Lazarian songs have their origin in the ancient carols and in particular can be considered as a continuation of the pagan Koleda carols. When Christianity came, the custom of carols survived and were adapted to the spring festivities of Lazarus Saturday. Lazaric carols are sung today in very few areas of Greece. The words of the songs refer to the resurrection of Lazarus but, the customs of Lazarus in the past had a social purpose.

For each song there was a separate dance. But special only in the details, special for the Lazarki who danced it, special for an experienced eye. Because all the dances were similar to each other. The Lazarki gave the differences in their dances with the movements of the body and especially with the movements of their hands. The woven towels, which they held in their hands and moved in front of them, gave a special grace to each dance. Finally, after each dance, in each house they gave the Lazarki eggs, baked goods or money as a gift.

They are dressed in pied dresses, with flowers on their heads and they dance and sing. They go to all the houses. They will have something to say for everyone.

Lazaritsa, the Saturday, was also a “rite of passage” performed by unmarried girls. The ritual became a way for the young girls to be noticed for the engagements that were waiting for them. Originally, they would wear their traditional Macedonian costume but after WWII and the Greek Civil War, girls would dress with the times looking their best for possible future suitors. Today, in some towns and villages of Macedonia, girls of all ages (married & unmarried) participate in the “Feast of Lazarus.” In some places, the traditional local costumes are coming back with mostly religious songs being used.

Stories of Discrimination, and Assimilation (Cultural Genocide)

One one occasion the young girls were going from house to house singing the traditional Macedonian songs, and another group of girls happened to hear these songs and informed the school teacher named Periklis. Upon attending school the first day back the week after, the teacher called all the girls into his office and preceded to interrogate them. He asked if they had sung Bulgarian songs, to which they replied, “these are the songs we have been taught since childhood by our grandmothers and mothers.” The teacher Periklis, told the girls he would let them off the hook this time but, to never sing in Bulgarian again or else they would be severely punished and they would not be given “Sisipio” – a daily breakfast treat. The girls would ask each other, why the teacher/s called their language Bulgarian when they knew that it was Macedonian.

On another similar occasion 8 year old “Voula” was so terrorized not to ever sing/speak Bulgarian (Macedonian) again or else her tongue would be cut off. Till the day Voula died, she never spoke Macedonian ever again. When ever her siblings, friends or acquaintances spoke to her in Macedonian, she would always reply in Greek.

Though an integral part in the cycle of a few great Christian feasts, the folklore celebrations of Lazarića (equivalent of the Feast of Saint Lazarus) represent a resurrection of nature, of youth and the hope for a new beginning. . In the past, the celebrations were many and varied, but today they have been mostly forgotten.

Sources:

Abbott, G. F. (2011). Macedonian folklore. Cambridge University Press.

Bozhinov, T. (2016, April 23). Bulgaria celebrates Lazarus Saturday (Lazaritsa) and Palm Sunday (Tsvetnitsa)! http://www.kashkaval-tourist.com. https://www.kashkaval-tourist.com/bulgaria-celebrates-lazarus-saturday-lazaritsa-and-palm-sunday-tsvetnitsa/

Blanchet, J. (1918). Traditional dance “oro”, village Negochani (Niki) [Photograph]. Macedonia1912-1918.blogspot.com. https://macedonia1912-1918.blogspot.com/2017/02/negochani-village-niki-during-ww1.html

Choleva, M. (2018, March 31). Το Σάββατο του Λαζάρου, τα έθιμα, τα κάλαντα και τα Λαζαράκια. Mother’s Bird. https://mothersbird.gr/savvato-toy-lazaroy-ta-ethima-ta-kalanta-kai-ta-lazarakia

Δαλαμπής, Ν. (1963). Περιγραφή του εθίμου “οι Λαζαρίνες” όπως γίνεται στο χωριό Πολύφυτο του νομού Κοζάνης. Μακεδονικά, 5(1), 244-252. doi: https://doi.org/10.12681/makedonika.793

Greek traditions for the Saturday of Lazarus. (n.d.). MYSTAGOGY RESOURCE CENTER. https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2011/04/greek-traditions-for-saturday-of.html

Ιωάννου,, K. Δ. (2019, March 21). Η Μακεδονική Γλώσσα και τα κατά συνθήκη ψεύδη (του Κώστα Δ. Ιωάννου). ΗΧΏ Φλώρινας. https://echoflorina.gr/%ce%b7-%ce%bc%ce%b1%ce%ba%ce%b5%ce%b4%ce%bf%ce%bd%ce%b9%ce%ba%ce%ae-%ce%b3%ce%bb%cf%8e%cf%83%cf%83%ce%b1-%ce%ba%ce%b1%ce%b9-%cf%84%ce%b1-%ce%ba%ce%b1%cf%84%ce%ac-%cf%83%cf%85%ce%bd%ce%b8%ce%ae%ce%ba/

Konstantinova, D. (n.d.). Lazaritsa and Tsvetnisa. БНР Новини – най-важното от България и света. https://bnr.bg/en/post/100385512/lazaritsa-and-tsvetnisa

Macedonian Cuisine. (2016, April). Cvetnici – Christian orthodox holiday a week before easter. WELCOME TO MACEDONIAN CUISINE ~ Macedonian Cuisine. https://www.macedoniancuisine.com/2016/04/cvetnici-christian-orthodox-holiday.html

Μισιρλή, B. E. (2020, April 11). Το έθιμο του Λαζάρου στο Λέχοβο. LehovoNEWS24.gr. https://www.lehovonews24.gr/to-ethimo-tou-lazarou-sto-lechovo/

Mythosphere. (n.d.). Macedonian mythology. World Mythology | Mythosphere. Retrieved April 13, 2025, from https://www.folklore.earth/culture/macedonian/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Народна лирика. (2005, November 6). Кајгана форум. https://forum.kajgana.com/threads/%D0%9D%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0.1835/

Petkovski, Filip. “The Women’s Ritual Processions ‘Lazarki’ in Macedonia.” Venets: The Belogradchik Journal for Local History, Cultural Heritage and Folk Studies, Vol. 5, No. 1, 2014. https://oaji.net/articles/2014/584-1418320865.pdf

Petkovski, B. (2018, March 13). Lazarice. International Festival of Ethnological Film. https://www.etnofilm.org/index.php/en/in-competition-meni/lazarice-filmed-reconstruction-of-lazarice-female-ritual-processions-from-the-ethnic-area-of-dolni-polog

Σάββατο του Λαζάρου: Έθιμα από όλη την Ελλάδα, Κάλαντα, Λαζαρίνες και «λαζαράκια». (2018, March 31). Sentra. https://sentra.com.gr/savvato-tou-lazarou-ethima-apo-oli-thn-ellada-kalanta-lazarines/

Saturday of Lazarus. (2020, April 11). Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church. https://holytrinitynr.org/sunday-school-online/saturday-of-lazarus

Στιγμές από το παρελθόν της Φλώρινας. Οι Λαζαρίνες. (n.d.). Florina History. https://florina-history.blogspot.com/2012/04/blog-post_08.html

Σ. Σ. (n.d.). Κάλαντα του Λαζάρου. Σαν Σήμερα .gr. https://6llef2ma2qleo3htgt3khtoafy-jj2cvlaia66be-www-sansimera-gr.translate.goog/articles/584/174

Τα Πασχαλινά έθιμα της της δυτικής Μακεδονίας: Από το Σάββατο του Λαζάρου έως την Ανάσταση. (2018, March 30). topontiki.gr. Retrieved May 23, 2021, from https://www.topontiki.gr/2018/03/30/ta-paschalina-ethima-tis-tis-ditikis-makedonias-apo-to-savvato-tou-lazarou-eos-tin-anastasi/

Τζιρίτας, O. Σ. (2016, April 24). Λαζαράκια, Λαζαρίνες και τα κάλαντα του αναστηθέντος Λαζάρου. Αρχική – Musicpaper.gr. https://www.musicpaper.gr/editorial/item/7719-lazarakia-lazarines-kai-kalanta-tou-anastithentos-lazarou

Τι πρέπει να γνωρίζουμε για το έθιμο των Λαζαρίνων? (2019, April 16). Donnasito. https://donnasito.gr/%CF%84%CE%B9-%CF%80%CF%81%CE%AD%CF%80%CE%B5%CE%B9-%CE%BD%CE%B1-%CE%B3%CE%BD%CF%89%CF%81%CE%AF%CE%B6%CE%BF%CF%85%CE%BC%CE%B5-%CE%B3%CE%B9%CE%B1-%CF%84%CE%BF-%CE%AD%CE%B8%CE%B9%CE%BC%CE%BF-%CF%84%CF%89/

Το Σάββατο του Λαζάρου – Παιχνίδια στην κουζίνα | 3ο ΝΗΠΙΑΓΩΓΕΙΟ ΙΛΙΟΥ. (2020, April 11). Εκπαιδευτικές Κοινότητες & Ιστολόγια ΠΣΔ. https://blogs.sch.gr/3nipiliou/2020/04/11/to-savvato-toy-lazaroy-paichnidia-stin-koyzina/#prettyPhoto