Prelude to ABECEDAR: The Language battle over Macedonia

At the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, daily Macedonian life in Zelenich was a microcosm of what was happening in the Monastir (Bitola) region and western Macedonia. The Balkan churches engaged in a fierce contest for jurisdictional dominance. The religious struggle in Macedonia was conducted primarily through the Greek Patriarchate and the Bulgarian Exarchate. Greece and Bulgaria not only used religion to assimilate people to their camp but most importantly, language used that automatically came with the specific camp often superseded the native Macedonia language.

This religious rivalry over Macedonian Christians culminated in the establishment of foreign religious organizations. Specifically, the Greek, Serbian, and Bulgarian churches sought to expand their jurisdictions in line with the territorial ambitions of their respective national states. Consequently, religious jurisdiction was viewed as a way of outwardly marking people and villages as belonging to the nationality of the associated church. By securing religious jurisdiction over Macedonia, each party could gain control over language use by marking people and villages as belonging to the nationality of the associated church.

Throughout this struggle for the souls of Macedonia, the people maintained a powerful connection to their church, and through their church, they preserved a strong bond with their language. Without a recognized independent Macedonian church (which had been abolished by the Ottomans in 1767), the Macedonian people were vulnerable to the influence of neighbouring religious propaganda.

Zeleniche is one of the oldest villages in the region, dating back to around 1396. According to oral history, the people who settled in Zelenich came from a village or town called ‘Sebaltsi/Seblatsi’ on the shores of Lake Zazari. The village is first mentioned in an Ottoman defter from 1481 under the name Zelenich. From the beginning, the language spoken by the inhabitants was referred to as Macedonian.

Only after the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchist Church in 1870 did the villagers choose to affiliate with the Exarchist Bulgarian Church rather than the Patriarchist Greek Church. Being called ‘Bulgarian’ indicated a religious affiliation with the Bulgarian Church, not an ethnic designation. Church services and the language spoken in the village remained Macedonian (even before 1396 CE), and not Bulgarian.

Schools

Alongside their efforts to establish and expand religious jurisdiction in Macedonia, the external Balkan states sought to reinforce their positions through the creation of educational institutions. Vast sums were spent by the governments of Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia to fund campaigns aimed at attracting children from the Macedonian Christian population to their respective Greek, Bulgarian, and Serbian schools. Religious jurisdiction was leveraged to support ethnographic and statistical claims. The Balkan states recognized that by establishing schools in Macedonia, they could strategically use the number and location of ‘their’ schools as evidence to demonstrate to Europe that their population inhabited Macedonia, or specific regions of it, in line with their territorial ambitions.

Educational activities sponsored by the Greek, Serbian, and Bulgarian governments had divisive effects on the unity of the Macedonian people, as each side sought to replace one form of domination with another and impose a new sense of identity on the Macedonians. Macedonia became an arena where rival parties fought for the minds of generations of Macedonian children. However, despite the presence of foreign teachers, students lacked the basic language skills to speak Bulgarian, Greek, or Serbian. They continued to speak their native language, Macedonian, both among themselves and with their teachers.

According to a 1901 letter from the Monastir Metropolitan Ambrosios to the Greek Patriarchate... the Greek Patriarchate school system failed to achieve its goal of introducing the Greek language to Macedonian children in the Monastir region.

Initially, the Bulgarians attracted students to their Exarchist schools by offering free attendance, whereas parents had to pay to send their children to the Greek Patriarchate schools. However, in the early 1900s, especially after 1903, the Patriarchate began targeting poor families by offering money and food. Macedonians, Vlachs, and Albanians were incentivised to become pro-Greek and send their children to Greek schools. Serbian support was typically secured only after significant financial expenditure; children were encouraged to attend Serbian schools with offers of free food, books, and even clothing.

In the case of Zelenich, the local dynamics illustrate this balance. St. George’s church remained under the Exarchist jurisdiction, reflecting the support it received from the Bulgarian Exarchist church. The presence of two Bulgarian-sponsored schools, which taught students in Macedonian rather than Bulgarian, indicates a localized approach to education that accommodated regional identities while still aligning with broader Bulgarian interests.

Conversely, the four families that opted to join the Patriarchist side were permitted to utilize St. Demetrius church, which served their interests through the establishment of a Greek school. This situation highlights the ongoing competition and negotiations between the Bulgarian Exarchate and the Greek Patriarchate, as both sought to establish their influence in the area.

Overall, the law on religion exemplifies the Ottoman Empire’s attempts to navigate the intricate web of ethnic and religious affiliations within its borders, attempting to maintain order and mitigate conflict among its diverse populations.

According to Dimitar Mishev’s account in La Macedoine et sa Population Chrétienne, the demographic landscape of Zelenich in 1905 was diverse and reflective of the broader ethnic tensions in Macedonia. The population included 1,656 Macedonian Exarchists, 192 Macedonian Patriarchists, and 102 Gypsy Christians, indicating a significant presence of different Christian communities within the village. The existence of two Macedonian schools and one Greek school suggests a structured educational system catering to the various ethnic groups, with efforts to promote their respective languages and cultures.

The teachers in Zelenich – V. Pliakov, Bl. Tipev, G. Drandarov, L. Dukova, A. Hristova, B. Karamfilovich, and D. Ghizova – demonstrate local involvement in education, with several being villagers themselves. This local engagement likely fostered a sense of community and cultural identity among the students. By 1907, the presence of a church with two priests serving the Macedonians in Zelenich highlights the importance of religious institutions in maintaining community cohesion and identity.

Hristo Silyanov’s description of Zelenich as a “beautiful, large village” with a more urban atmosphere suggests it was a vibrant centre of activity, possibly with a mix of agricultural and commercial pursuits. The mention of men wearing trousers, along with the characterization of the villagers as tame, receptive, and friendly, paints a picture of a community that was open and engaged, contributing to the social fabric of the region amidst the complexities of ethnic and religious identities. This environment likely facilitated interactions among different groups, shaping the village’s cultural landscape.

In Zelenich and many other villages in Macedonia under the jurisdiction of the Greek Patriarchate, church services were conducted in the Western Macedonian dialect. This practice highlighted the community’s efforts to maintain and promote their local language and cultural identity within the church, especially through the use of the dialect that eventually found its way into the “ABECEDAR” primer. This primer served as an educational tool, reflecting the region’s linguistic heritage among the Macedonian population.

In contrast, in larger towns, church services were conducted in Greek, a language that many locals may have perceived as foreign and imposed upon them. This divergence between rural and urban practices underscores the complexities of ethnic and national identity in Macedonia during this period. While rural communities in villages like Zelenich were able to conduct services in their own dialect, reflecting their cultural heritage, urban centres often represented a more cosmopolitan environment where Greek influence was stronger.

The imposition of Greek in urban church services contributed to tensions between different ethnic groups, particularly as the Greek Patriarchate sought to assert its authority over the Macedonian population. This bilingual dynamic—local dialect in villages versus Greek in towns—demonstrates the broader struggles for cultural autonomy and national identity within Macedonia during the late Ottoman period.

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, the majority of the rural population in Macedonia spoke Macedonian as their mother tongue, reflecting the region’s linguistic and cultural heritage. However, this linguistic unity was increasingly challenged by political and ethnic conflicts, especially from 1903 to the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. During this period, foreign armed bands—often aligned with nationalistic movements—terrorized local populations in small towns and villages, creating a climate of fear and instability.

The choice of affiliation with either the Bulgarian Exarchate or the Greek Patriarchate had significant repercussions for local communities. These affiliations not only impacted religious practices but also influenced educational policies and the language used in church services. The language of worship became a crucial battleground for ideological control, as it was leveraged as a form of propaganda to promote the interests of Greek, Bulgarian, and Serbian nationalistic factions.

In this context, church services in different languages served not only as spiritual gatherings but also as platforms for cultural and national education. Each church sought to instill its narrative and identity within the local populace, using the language spoken in services as a means to achieve desired outcomes. This manipulation of religious language further exacerbated ethnic tensions, as communities found themselves caught between competing nationalism’s, with each side vying for loyalty and support.

The impact of this period on the Macedonian population was profound, as the struggle for national identity was intertwined with religious affiliation and language, leading to significant divisions within the community and setting the stage for further conflict in the region during and after the Balkan Wars.

Minority Languages in 19th and Early 20th Century Macedonia

In the 19th century, a diverse array of languages was spoken in the Macedonian region, reflecting its complex ethnic and cultural landscape. The primary languages included Turkish, Macedonian (Slavic), Albanian, Vlach, Greek, Hebrew-Spanish, and Romany. Among these, Macedonian was the mother tongue for the vast majority of the rural population, with smaller communities speaking Albanian, Vlach, and Turkish.

In this multilingual society, men were generally familiar with several languages, while women typically spoke only their native tongue. Both Greek and Turkish held dominant positions: Turkish in administration and Greek in commerce and religion. Despite the growing influence of these languages, Macedonian remained the primary cultural language for the indigenous population.

However, when the role of the Bulgarian Exarchist Church gained prominence, Bulgarian language and influence expanded at the expense of Greek, especially in religious settings. Yet Macedonian continued to serve as the cultural pillar for native speakers especially in western Macedonia and Zelenich. This was evident in Salonika in the early 20th century, when students in boys’ schools revolted against the introduction of Bulgarian as the language of instruction, refusing to be taught in it.

The Millet System and the Role of Religion

During the Ottoman era, religious affiliation, rather than ethnicity, defined identity under the Millet system. This system labelled individuals based on their religious allegiance: those who followed the Greek Patriarchate were considered Greek, while those aligned with the Bulgarian Exarchate were labelled Bulgarian. Greece and Bulgaria used this administrative system to claim the Macedonian population, as it suited their respective political aspirations to assimilate the region.

This religiously based system allowed both nations to avoid recognizing ethnic distinctions, which would have undermined their efforts to control Macedonia. Greek and Bulgarian claims over the Macedonians were bolstered by the creation of foreign schools, where education became a tool of indoctrination.

Assimilation Through Religion, Education, and Violence

In the second half of the 19th century, both Greece and Bulgaria opened numerous primary and secondary schools across Macedonia, teaching in Greek, Bulgarian, and Aromanian. Many villages had multiple schools, each offering education in a different language. Bulgarian schools proliferated in Western Macedonia, particularly in villages like Sklithro (Zelenich), where the population had aligned with the Bulgarian Exarchate. Despite the presence of a Greek school in Zelenich, only four families supported it, while the majority sent their children to the two Bulgarian schools.

In 1913, following the Balkan Wars, Greek authorities shut down the Bulgarian schools, although Aromanian schools remained operational until 1940.

Throughout the early 20th century, both Greece and Bulgaria pursued aggressive assimilation policies in Macedonia. Initially, they used religion and priests to sway the local population, followed by sending teachers to indoctrinate students in foreign schools. Ultimately, these efforts were backed by paramilitary groups that terrorized and murdered local Macedonians who resisted conversion to either Greek or Bulgarian national identities.

This violent process of forced assimilation culminated in the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, during which Greek and Bulgarian armies committed atrocities against the Macedonian population. In their respective campaigns to occupy Macedonia, both nations sought not only to conquer the land but also to erase the distinct ethnic identity of its people, committing acts of genocide in the process.

ABECEDAR

Since Aegean Macedonia was integrated into Greek territory in 1913, the Greek authorities adopted an extremely negative official policy towards the Macedonian language. This stance was part of a broader national strategy aimed at promoting Greek identity and suppressing regional languages and cultures that were perceived as threats to national cohesion.

In the early years following the integration, particularly during the 1920s, the situation was somewhat more complex. The language was occasionally referred to as “Macedonian,” acknowledging the existence of a distinct Slavic-speaking population within the region. This recognition indicated an awareness, albeit limited, of the linguistic diversity present in Aegean Macedonia. However, this acknowledgement was short-lived and did not translate into any significant support or rights for the speakers of the Macedonian language.

Policy of Hellenization

As the Greek state pursued its policy of Hellenization, the use of the Macedonian language faced increasing repression. Educational institutions were discouraged or outright banned from teaching in Macedonian, and public use of the language was often met with hostility. This suppression was part of a larger effort to assimilate Slavic-speaking populations into the Greek national identity, which involved promoting Greek as the sole language of education, administration, and public life.

Despite these challenges, the early recognition of the Macedonian language highlighted the complexities of identity and linguistic diversity in the region, as well as the resistance of local communities to the imposition of a singular national identity. The long-term effects of these policies have had lasting impacts on the cultural and linguistic landscape of Aegean Macedonia and the broader Balkan region.

The Treaty of Sèvres, signed on August 10, 1920, was a significant international agreement that aimed to outline the post-World War I settlement and address various territorial and national issues in the region. Among its provisions, the treaty included obligations for the Greek government regarding the protection of non-Greek national minorities within Greece.

Article 7: “All Greek citizens will enjoy equal civil and political rights regardless of their ethnicity, language or religion. Greece, in particular, is undertaking the obligation to introduce, within three years from the date as of which this Treaty will come into force, electoral system which will take into account the ethnic minorities..”

“No legislation will be made on any restrictions on the free use by any Greek citizen of any language, either in their private intercourse, in commerce, in religion, in the Press or in publications of any kind, or at public meetings.. .”

Article 8: “Greek citizens belonging to separate ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities, will enjoy equality of rights and treatment, and the same guarantees, as other Greek citizens. They shall, for instance, have the right to establish, manage and control at their own expense charitable, religious and social institutions and educational establishments, as well as the right to use their own language in them and to practice their particular religion.”

Article 9: “As regards education, in the towns and districts inhabited by a larger number of citizens of non-Greek language, the Greek government shall make adequate facilities enabling the children of such Greek citizens to receive instruction in elementary schools in their mother tongue. . .”

Summary of Articles 7, 8, and 9 of the treaty explicitly stipulated the following:

1. Free Use of Language: The Greek government was obligated to ensure that minority groups had the right to use their own languages in both private and public life. This recognition of linguistic rights was intended to promote cultural diversity and protect the identities of non-Greek communities.

2. Education: The treaty emphasized the right of minorities to receive education in their own languages. This provision aimed to support the preservation of minority cultures and ensure that these communities could educate their children in a language that was familiar to them, thus fostering a sense of identity and continuity.

3. Religious Practice: Article 9 addressed the freedom of religious practice for minority groups, guaranteeing their rights to maintain and observe their religious traditions and institutions without interference from the state. This recognition was essential for the cultural and spiritual well-being of non-Greek communities, allowing them to practice their faith freely.

Despite these provisions, the implementation of the Treaty of Sèvres faced numerous challenges. The Greek government’s commitment to protecting minority rights was often inconsistent, and many non-Greek-speaking communities continued to experience repression and marginalization. The aftermath of the treaty, coupled with the rise of nationalist sentiments, further complicated the situation for minorities in Greece, including the Macedonian population.

Ultimately, while the Treaty of Sèvres represented a recognition of minority rights, its practical effects were limited, and the protection of non-Greek national minorities in Greece remained a contentious issue in the years that followed.

In 1924, the Kalfov-Politis Protocol was signed between the governments of Greece and Bulgaria, facilitated by the League of Nations. This agreement was a significant development in the context of interwar Balkan politics and reflected the complex relationship between the two nations regarding their respective ethnic minorities.

Under the terms of the Kalfov-Politis Protocol, the Greek government, while maintaining a facade of goodwill, recognized the Macedonians of the Aegean part of Macedonia as a “Bulgarian” minority in Greece. This recognition was notable because it acknowledged the existence of a distinct Slavic-speaking population in the region, but it framed this identity within the context of Bulgarian nationalism.

The protocol aimed to address some of the grievances stemming from the treatment of ethnic minorities, particularly following the aftermath of World War I and the Treaty of Sèvres. However, the Greek government’s recognition of Macedonians as “Bulgarian” was ultimately a strategic move. It allowed Greece to appease international concerns regarding minority rights while simultaneously undermining the distinct identity of the Macedonian population. This labelling of Macedonians as Bulgarian contributed to the erasure of their unique cultural and linguistic identity and reinforced the narrative that aligned them with Bulgarian nationalism.

In practice, the implementation of the Kalfov-Politis Protocol did not lead to substantial improvements in the rights and conditions of Macedonian communities in Greece. The Greek government’s policies continued to prioritize Hellenization, leading to further repression of the Macedonian language and culture. The complexities of ethnic identity in the region were thus exacerbated by this agreement, as it attempted to navigate the fraught landscape of national identities in post-war Greece while concealing underlying intentions that often-favoured Greek nationalism over minority rights.

However, shortly after this concession, the Greek government retracted its position by denying the Bulgarian government any rights or interests in the Macedonian population within Greece. This shift reflected a broader strategy of the Greek state to assert its sovereignty and promote a singular Greek national identity, thereby rejecting any external claims over the Macedonian community.

By claiming that the Macedonian population in Greece was not a Bulgarian minority, the Greek government effectively aimed to erase the acknowledgement of a distinct Macedonian identity. This denial served to reinforce the narrative of Hellenization and to mitigate any potential Bulgarian influence in the region. The Greek state maintained that all citizens, regardless of ethnic background, were Greeks, thereby invalidating any claims to a separate Macedonian identity that could align with Bulgarian nationalism.

This flip-flop in policy illustrated the tensions inherent in the region’s ethnic dynamics, where national identities were frequently contested, and the rights of minority populations were often subordinated to broader geopolitical considerations. The repercussions of these policies contributed to the ongoing struggles for recognition and rights faced by Macedonian communities in Greece, as well as the broader implications for regional stability and interethnic relations.

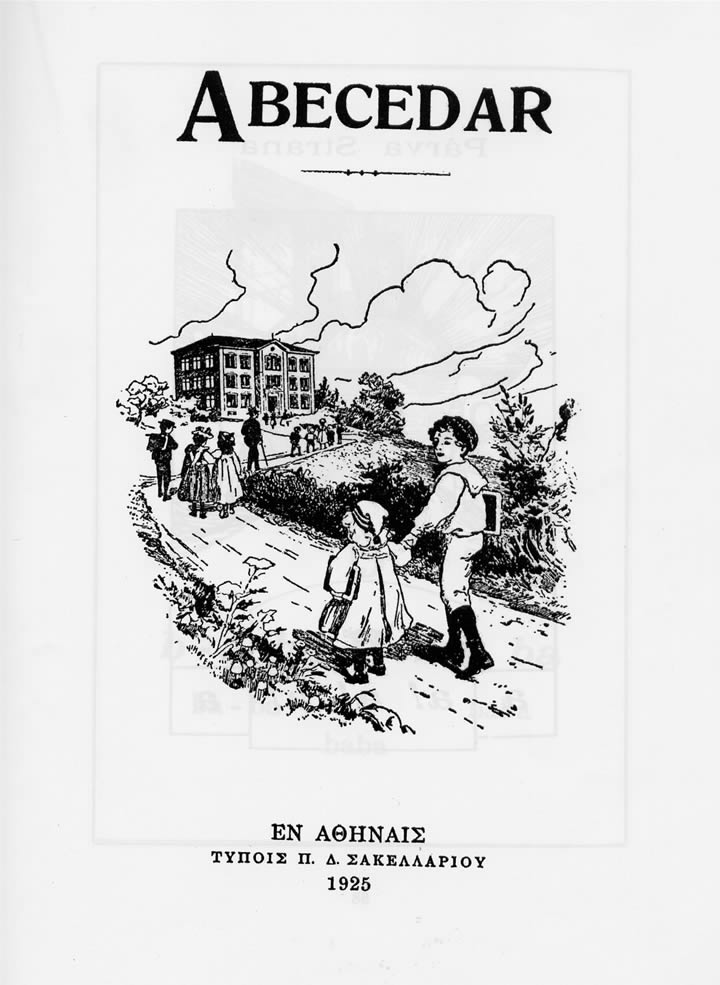

The Greek government’s publication of the Abecedar in 1925, written in the Latin alphabet, marked a significant moment in the treatment of the Macedonian language and identity. While the government claimed the publication was intended for the Slavic-speaking population in Greece, it is widely recognized that the primary audience was indeed the Macedonians, who were asserting their distinct identity separate from both Bulgarian and Greek national narratives.

“Acknowledging Macedonian Identity and Language”

The evidence provided underscores the complexity of ethnic identity and linguistic designation in the region during this time. Several notable figures and texts highlighted the acknowledgement of the Macedonian identity and language as follows:

1. George Demetrios in his memoir When I Was A Boy In Greece (1913) articulated that the people he encountered were referred to as “Bulgarian” by the Greeks, yet their language was distinctively identified as Macedonian. This differentiation emphasizes the recognition of a unique cultural identity that transcended national labels.

2. Ion Dragoumis, a prominent diplomat and writer, argued in 1924 that “Macedonian” was the correct term for the language spoken by the inhabitants of Macedonia, asserting its legitimacy as a distinct linguistic category.

3. Peter Mackridge noted that up until the 1930s, it was generally acceptable for Greeks to refer to the Slav language spoken in Macedonia as “Macedonian” and its speakers as “Macedonians.” This indicates a broader social acceptance of the term, and an acknowledgment of the distinct identity associated with it.

4. Stratis Myrivilis, in his novel Life in the Tomb (1924), reflected the sentiments of many locals who did not identify with Bulgarian, Serbian, or Greek national identities but rather embraced their Macedonian identity.

5. Pinelopi Delta, in her 1937 work In the Secret Places of the Marsh, continued to refer to the local Slavonic language as “Macedonian,” reinforcing the notion of a specific linguistic and cultural identity.

6. The Diary of David Hunter Miller, an American diplomat, discussed the Macedonian minority during the post-war period, further highlighting international recognition of this identity.

7. Bartello, a principal author of the Treaty of Sèvres, also acknowledged the Macedonian minority, emphasizing its presence in diplomatic discussions.

8. Other figures such as Grigorios Dafnis and Dimitrios Vazuglis noted the existence of the Macedonian minority in their writings, contributing to the documentation of ethnic diversity in Greece.

9. Ioannis Sofianopulos, a politician and leftist leader, reflected on the Balkan dynamics and acknowledged the distinct identity of the Macedonian population.

Collectively, these accounts and observations illustrate a complex landscape in which the Macedonian identity was both recognized and contested. Despite the Greek government’s efforts to suppress this identity in favour of a singular Greek narrative, there was a notable acknowledgement of the Macedonian language and culture in various literary, diplomatic, and historical contexts. This duality highlights the ongoing struggles faced by the Macedonian population in Greece as they navigated their identity amidst nationalistic pressures and the socio-political climate of the time.

Addressing International Agreements

Under pressure from the League of Nations, the Greek government took concrete steps to address the concerns of ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities, particularly in the wake of other international agreements. One of the most notable actions was the establishment of a special department within the Ministry of Education, specifically tasked with managing the issues related to these minorities.

This department was responsible for:

1. Overseeing Minority Education: The department was tasked with developing and implementing educational programs tailored to the needs of Greece’s minority populations. This included creating curricula and instructional materials in minority languages, such as Macedonian, to ensure that minority children could receive education in their mother tongue. The publication of the Abecedar in 1925 was one such initiative, though it was limited in its reach and effect.

2. Ethnic and Linguistic Research: The department was also responsible for gathering information and conducting research on the ethnic composition and linguistic practices of the minority populations. This included identifying the specific needs of these communities and ensuring that appropriate educational provisions were made.

3. Cultural and Religious Rights: Alongside linguistic education, the department’s mandate extended to protecting the cultural and religious practices of the minority groups, in line with international agreements like the Treaty of Sèvres. This involved coordinating with local authorities and religious institutions to ensure that these rights were respected, although implementation was often inconsistent.

Greek Authorities focused on promoting Hellenization

Despite these steps, the Greek government’s approach to minority education and rights was largely shaped by broader nationalistic policies aimed at homogenizing the population. The formation of this department reflected international pressure to comply with treaties and obligations, but the underlying intention of the Greek authorities often remained focused on promoting Hellenization. This resulted in limited and sometimes tokenistic efforts to support minority languages and cultures, as seen in the eventual suppression of the Abecedar and the restrictions placed on minority schools and cultural expression in subsequent decades.

The creation of this special department within the Ministry of Education illustrates Greece’s balancing act between international expectations and domestic nationalistic goals, as it sought to integrate and control its diverse minority populations while maintaining a Greek national identity.

Abecedar was Praised

The publication of the Abecedar in 1925, intended for the Slavic-speaking population of Greek Macedonia and Western Thrace, was a noteworthy development in Greece’s approach to minority education. As highlighted by the publicist Nikolas Zarifis in Eleftheron Vima on October 19, 1925, the Abecedar was praised as a carefully prepared and conscientious effort by specialists, including Papazahariu, Saiktsis, and Lazaru, to meet the educational needs of the Slav-speaking minority in Greece. Zarifis described the Abecedar as a complete primer based on the Macedonian dialect, written in the Latin alphabet.

Zarifis’ commentary reflects the broader significance attributed to the Abecedar at the time. It was designed to be used in schools for the minority population, addressing the linguistic realities of the region where many people spoke a Slavic language, distinct from Greek. The use of the Latin alphabet, rather than Cyrillic, was likely a political decision to distance the Macedonian dialect from Bulgarian and Serbian influence and to minimize any association with Slavic nationalism, especially given the tensions in the Balkans during that period.

Zarifis’ praise in Eleftheron Vima underscored the Greek government’s attempt, at least publicly, to comply with international expectations regarding minority rights. The Abecedar was portrayed as a tool to provide education in the mother tongue of the Slav-speaking minority, marking a shift toward addressing minority needs in a formal educational setting.

Implementation of the Abecedar was Limited

However, despite this initial optimism and publicity, the practical implementation of the Abecedar was limited. The schools it was meant to serve were not widely established, and the Greek state’s broader policy of Hellenization continued to overshadow efforts to support minority languages. Over time, the use of the Abecedar and its associated educational reforms faded, as Greece shifted away from minority accommodations, particularly in the context of growing nationalism and the state’s desire to create a more homogeneous national identity.

The Greek government’s efforts in the mid-1920s to establish educational programs for the Slav-speaking Macedonian minority, including the publication of the Abecedar, were largely driven by international pressures, particularly from the League of Nations. The school inspectors in the Macedonian districts were tasked with creating specialized teaching programs for classes consisting of Macedonian children, signaling a formal acknowledgement of the need to address the linguistic and educational needs of this minority.

Everything was set for the opening of schools specifically designed to serve the Slav-speaking population, which was largely Macedonian. These schools were meant to demonstrate Greece’s compliance with the international agreements regarding minority rights, particularly those outlined in the Treaty of Sèvres (1920). The Treaty required Greece to respect the rights of its ethnic minorities, including the protection of their languages, education, and religious practices.

By taking these steps, the Greek government sought to showcase its willingness to implement the stipulations of these international treaties and thereby gain the approval and praise of the League of Nations. The League was actively involved in overseeing minority rights across Europe in the aftermath of World War I, and Greece’s actions were aimed at projecting an image of a modern, compliant state that respected its minority populations.

Policy of Hellenization Dominates

However, these measures, while publicly promoted and seemingly progressive, were often more about fulfilling international expectations than about genuinely integrating and protecting the Macedonian minority. Despite the readiness for schools to open, the actual implementation of these programs was minimal, and the Greek government’s broader policy of Hellenization continued to dominate. Over time, the political environment in Greece grew increasingly hostile to the Macedonian identity, and these early initiatives were not realized, reflecting the state’s reluctance to support a distinct Macedonian cultural or linguistic presence within its borders.

The reciprocal agreements between Greece and Bulgaria regarding the protection of their respective minorities, particularly the signing of the “Lesser Protocols” on September 29, 1924, under the auspices of the League of Nations, played a pivotal role in shaping the demographic and cultural landscape of the region during this period. These protocols aimed to protect the rights of the Greek minority in Bulgaria and the Bulgarian minority in Greece, especially in the wake of the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), which included provisions for the protection of ethnic minorities.

However, the implementation of these agreements led to significant population movements, often under coercion. Bulgaria, seeing the agreement as an opportunity to further its influence among the Macedonian population, launched a campaign in support of the activities initiated by the Joint Greek Bulgarian Commission for the so-called “voluntary” exchange of minorities. This commission was responsible for overseeing the relocation of populations based on ethnic and religious criteria.

Population Exchanges

As a result, large numbers of Macedonians, who were often identified as Bulgarian or Slavic speakers, were forcibly moved from the Aegean part of Macedonia (now part of Greece) to Bulgaria. These population exchanges were framed as voluntary, but in practice, many Macedonians were pressured to leave their homes. The process caused significant displacement and hardship for the affected communities, disrupting the social fabric of the region.

Simultaneously, Greece sought to consolidate its control over the Aegean part of Macedonia by bringing in Orthodox Christian settlers from Turkey, Bulgaria, and other regions. This movement of populations was part of a broader strategy of Hellenization, whereby Greece aimed to solidify its national identity in areas with significant minority populations. The arrival of Greek Orthodox refugees from the Asia Minor catastrophe in 1922, alongside other Christian populations, was particularly significant in reshaping the ethnic and religious composition of the Aegean part of Macedonia.

These population exchanges, conducted under the guise of protecting minority rights, had a profound and lasting impact on the region. The forced displacement of Macedonians to Bulgaria and the influx of Christian settlers into Macedonia contributed to the erasure of local identities and the homogenization of the population along national and religious lines. This process further marginalized the Macedonian minority, whose cultural and linguistic identity was often suppressed in favor of the dominant Greek national narrative.

In the broader context of Balkan politics, these actions reflect the ongoing struggle among Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia for influence over Macedonia, a strategically and symbolically important region. The forced migrations, alongside the tensions over minority rights, highlight the complex and often painful process of nation-building in the post-World War I Balkans, where ethnic diversity was frequently seen as a challenge to the creation of homogeneous nation-states.

Addressing the Macedonian-speaking population

The Abecedar, published in 1925, was a key element in the Greek government’s approach to addressing the Macedonian-speaking population in the Aegean part of Macedonia. By using the Latin alphabet for the primer, Greek authorities sought to distance the Macedonian language from both Bulgarian and Serbian influences, making a clear distinction between these related Slavic languages. The dialect used in the Abecedar was based on the Bitola-Florina dialect, reflecting the speech of the local population in the region.

However, this approach was met with resistance not only from Bulgaria but also from Serbia. Both countries had vested interests in claiming the Macedonian-speaking population as part of their own ethnic and linguistic groups. Bulgaria viewed the Macedonian speakers as ethnically Bulgarian, while Serbia had similar aspirations regarding the population, considering them closer to Serbian identity. This rivalry over the Macedonian identity complicated Greece’s efforts to implement minority protections.

As a result of these geopolitical pressures, the Greek government took a cautious stance. It did not ratify certain clauses of the “Lesser Protocols” that would have given more explicit recognition to the Macedonian population as an ethnic minority. Instead, Greece chose to classify the Macedonian speakers as a “Slav-speaking minority” rather than acknowledging them as an ethnic group with a distinct identity. This linguistic classification allowed Greece to sidestep the broader ethnic and political implications of recognizing Macedonians as a distinct nationality, which might have fuelled claims from neighbouring Bulgaria or Serbia.

By treating the Macedonian-speaking population as a linguistic minority, Greece avoided aligning them with either Bulgaria or Serbia and maintained greater control over the region. However, this policy also limited the cultural and political recognition of the Macedonian population, contributing to the long-term marginalization of their identity within the Greek state.

This strategy was part of a broader effort by Greece to maintain national unity and territorial integrity, especially in regions like Macedonia, which were seen as vulnerable to external influence. The reluctance to fully implement the minority rights provisions of the Lesser Protocols reflected Greece’s concerns about the territorial ambitions of its neighbours and the potential for ethnic divisions within its own borders.

The publication of the Abecedar in 1925 was a significant moment in the history of minority rights for the Macedonian-speaking population in Greece. In response to the League of Nations’ pressure, the Greek government notified the League that it was taking measures to open schools for the Slav-speaking population (Macedonians) during the 1925/26 school year, as well as granting the freedom to practice religion in the Macedonian language. The Abecedar was presented as tangible evidence of Greece’s commitment to these efforts, serving as a primer for Macedonian children in the Aegean part of Macedonia.

What made this primer historically important was that, unlike earlier primers written in Macedonian and used in the 19th century, this was the first one published by a legitimate government—the Greek government—for its own citizens and under the supervision of the League of Nations. The Abecedar was not only an educational tool but also a diplomatic move to show that Greece was adhering to international obligations regarding minority rights.

Despite this, the Abecedar sparked immediate controversy and opposition from both Serbia and Bulgaria. Belgrade argued that the people for whom the primer was intended were “Serbs,” thus opposing the notion of a distinct Macedonian identity. Serbia claimed the Macedonian-speaking population as part of its own ethnic and national heritage. Similarly, Bulgaria asserted that the population was Bulgarian and not Macedonian. Sofia’s objections were rooted in the longstanding Bulgarian claim that Macedonian speakers were ethnically Bulgarian, despite the linguistic and regional differences.

Both Serbia and Bulgaria submitted petitions to the League of Nations, each asserting their own national claim over the Macedonian-speaking population. These petitions reflected the broader geopolitical struggle over Macedonia, where the identity of the population was a key point of contention among the Balkan states.

This conflict over identity complicated Greece’s attempts to establish a distinct Macedonian identity within its borders while appeasing international expectations. The decision to use the Latin alphabet for the Abecedar further distanced the Macedonian language from both Bulgarian and Serbian influences, underscoring Greece’s efforts to prevent the region from falling under the cultural or political sway of its neighbours.

In the end, the backlash from Serbia and Bulgaria, combined with domestic pressures and the broader nationalistic climate, meant that the schools and educational reforms promised in connection with the Abecedar were not fully realized. Though the primer was intended to be a step toward recognizing and accommodating the Macedonian-speaking minority, it became a symbol of the complex and often conflicting national interests surrounding the region of Macedonia in the early 20th century.

The Greek government’s acknowledgement in the 1920s that the population in certain villages “knows neither the Serbian nor the Bulgarian language and speaks nothing but a Slav-Macedonian idiom” marked a significant moment in the recognition of the Macedonian identity within Greece. This statement, made in response to international pressures, notably from the League of Nations, reflected Greece’s first official recognition of a distinct Macedonian-speaking population within its borders, though the government classified them as a “Slav-speaking minority” rather than an ethnic minority.

This distinction is of particular importance because it indicated that Greece did not view this population as part of the Bulgarian national identity, as Sofia claimed, nor as Serbian, as Belgrade contended. Instead, Greece acknowledged that the language spoken by this group was different from both Bulgarian and Serbian, referring to it as a Macedonian Slav dialect. The Abecedar primer, written in the Latin alphabet and based on the Florina-Bitola dialect (a variety of the Macedonian language), was a practical manifestation of this recognition.

The fact that Greece chose to publish the Abecedar in the Latin alphabet, rather than the Cyrillic alphabet used by Bulgarians and Serbs, was a deliberate move to avoid reinforcing claims by neighbouring countries over the Macedonian population. By distancing the Macedonian language from Bulgaria and Serbia, Greece aimed to assert greater control over the cultural and linguistic identity of this group within its own borders.

The publication and distribution of the Abecedar in Western Aegean Macedonia (in areas like Kostur, Lerin, and Voden) represented a concrete effort to provide education in the Macedonian language for children in the first through fourth grades. The primer’s use in these regions showed an official addressing the Macedonian-speaking population

Nevertheless, this recognition of a separate Slav-speaking group did not translate into full political or cultural acceptance of a Macedonian national identity within Greece. The Greek authorities’ reluctance to classify the Macedonians as an ethnic minority, instead referring to them as a linguistic group, was a reflection of broader national concerns about territorial integrity and foreign influence. While the publication of the Abecedar was a significant gesture, the Greek government continued to treat the Macedonian population cautiously, seeking to balance international obligations with domestic nationalist agendas.

This cautious recognition is further underscored by the fact that the Abecedar project was short-lived and never fully implemented in the educational system. The opposition from Bulgaria and Serbia, combined with internal Greek resistance to any formal recognition of a distinct Macedonian identity, limited the impact of the primer and the educational reforms promised at the time. Nonetheless, the Abecedar remains a symbolic moment in the history of Macedonian minority rights in Greece, representing a brief acknowledgement of their linguistic and cultural distinctiveness.

In early 1926, following the legislative decree issued in late 1925, the Greek government established a department in Greek Macedonia dedicated to the administration and supervision of non-Greek elementary education. This department was formed as part of the government’s attempt to address the educational needs of the minority populations in Macedonia, especially the Macedonian Slav-speaking community, in response to the pressures from the League of Nations and the provisions of the Treaty of Sevres.

The newly established Department of Non-Greek Education was managed by a group of experts that included three members from the educational council, appointed by the minister of education. Additional members included the director of the Second Political Department of the Foreign Ministry and three unpaid citizens from Macedonia, chosen by the foreign minister and appointed by the education minister. A key figure in the department was a counsellor of education, proficient in one of the local dialects, who was appointed head of the department for a three-year period. One of the department’s significant decisions was to ensure that teachers assigned to minority schools would be familiar with the local dialects, enabling them to provide relevant instruction to non-Greek-speaking students.

This department’s creation represented the first step in institutionalizing the education of minorities in Greece. The decision to employ the local Slavic dialect for instruction in minority schools was an acknowledgement of the linguistic diversity in Macedonia and the need to adapt educational policies to accommodate this diversity. The Greek government tasked a three-member committee of specialists with the development of the Abecedar primer, which was intended for use in these minority schools.

The three-member committee consisted of Georgios Sagiaxis, a prominent folklorist and linguist who had long been involved in the study of the Vlach-speaking and Slavic-speaking populations of Greece. Sagiaxis had studied abroad on a Foreign Ministry scholarship and brought considerable expertise in ethnography and linguistics. He was joined by two philologists: Iosif Lazarou and Papazachariou, both of whom were native Vlach-speakers with a strong understanding of the local Slavic dialect spoken by the Macedonian population. Together, these three specialists prepared the Abecedar, a primer that became a symbol of the Greek government’s efforts to address minority education within its borders, albeit with mixed outcomes.

The establishment of this department and the publication of the Abecedar were responses to international expectations and pressure, particularly from the League of Nations. However, the broader political climate, including resistance from neighbouring countries like Bulgaria and Serbia, as well as internal nationalistic pressures, complicated the full implementation of these educational reforms. While these efforts signalled progress, they were ultimately constrained by the realities of inter-Balkan tensions and domestic politics, which limited the long-term impact on the education and recognition of the Macedonian-speaking minority in Greece.

Apparent distribution of primer in Western Greek Macedonia

Greek authorities reported that the primer was introduced experimentally in the region of Sorovich (now Amyntaion). Apparently, it produced a fierce reaction that continued uninterrupted for several days where some teachers were harassed, and books were burned. On 1 February, Slavic-speakers and Greek-speakers alike were said to have joined in a demonstration in Amyntaion. The following resolution was drawn up and telegraphed to the Foreign Ministry:

“All the inhabitants and the parents of students attending the schools of Sorovic,

having been informed by our children about the introduction of the Slavic idiom

and sharing their just exasperation and protest regarding the introduction to

schools of an unwanted language, we have gathered willingly and spontaneously

today in exasperation and we unanimously express our pain for our government’s

unholy act to introduce an unwanted linguistic idiom.”

Despite its pompous and somewhat awkward wording, the message was clear: the Greek government had no real intention of supporting the implementation of the primer. Whether the protests and outrage were spontaneous or a fabrication, they served a critical purpose. The government found a convenient excuse to evade its obligations to the League of Nations, which mandated the protection of minority rights and the establishment of schools for non-Greek speakers.

Behind the scenes, the Greek government’s actions spoke volumes. Rather than supporting minority education, their policies were carefully designed to ensure its failure. For lack of funding, minority schools would not be established as separate institutions but instead forced to operate as classes within existing Greek schools. “The government intentionally introduced the primer to all students, Macedonian and Greek alike, with the specific goal of inciting conflict among Greeks by imposing Macedonian language education.” Worse still, the teaching of Greek in these minority classes was made compulsory, undermining the very purpose of educating students in their native languages.

This environment, fostered by precise instructions from the authorities, only fueled animosity, fear, and division. Macedonian students found themselves in a hostile climate where their language and culture were not protected but systematically marginalized. The government’s true agenda—Hellenization through forced assimilation—was clear. By promoting intolerance and fear under the guise of educational reform, they ensured that minority languages would never gain a foothold, while publicly maintaining a facade of compliance with international obligations.

However, after protests from Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia, Greece ultimately refused to ratify the Protocol. The Macedonian primer was withdrawn and plans to establish Macedonian-language schools were abandoned. Press coverage in all three Balkan monarchies expressed outrage, leading to intense and sometimes violent reactions. Under pressure to maintain its delicate Balkan alliances, Greece was forced to ‘retreat.’ Consequently, in May 1926, the project was formally shelved by the head of the Public Security Service, Georgos Fessopoulos, who argued that the Abecedar primer would incite public unrest and posed a threat to national security.

The Abecedar primer, created for Macedonian children, never reached its intended audience. Instead, it functioned solely as a tool for the Greek government to demonstrate to the Great Powers that it had ostensibly met its obligations under the Treaty of Sèvres. After this display, the primers were destroyed, and from then on, Greece denied the existence of Macedonians altogether. The state labelled them as “Slavophone Greeks,” “Old Bulgarians,” and other terms—anything but Macedonians.

Language of the Primer

Download the ABECEDAR (pdf)

The following links will give you information on:

- Main characteristics of the Abecedar

- Abecedar facts for kids

- Second and third editions

- Examples from the second edition of the book

- History of the Macedonian language

Summary:

Since Abecedar in 1925 the Greek authorities have taken a wide variety of measures in order to eradicate the use of the Macedonian language. Special care was taken to prevent the use of the language by civil servants serving in Slav-speaking areas. That this policy was still in force during the 1980s can be seen from a secret report entitled “Conspiracy against Macedonia” emanating from the Department of Public Order. This report contained, among others, the following “recommendations”, most of which were put into practice that:

- “All those who are employed, as clerks or as a helping staff, in the public service and more specifically, in the educational institutions, should not be familiar with the spoken local dialect”.

- “To establish appropriate conditions so that all public servants (i.e. Greek-speaking) and other clerks remain in their present jobs or areas of employment.”

- “The Army, the Security Authorities, the Public Service and other organisations that employ, in preference to other applicants, those applicants who come from the region of Florina only when they are sure that they can be posted to other parts of the country.”

- “The high command of the Army should encourage those soldiers who are doing their service in the region of Florina, but come from another parts of Greece, to get acquainted and to marry local women from Florina who speak the dialect.”

Macedonian Language Banned – Summary

1925 – 76 names of Macedonian villages and towns in Aegean Macedonia “Hellenized” since 1918 by Greek authorities.

- League of Nations pressures on Greece to extend rights to Macedonian minority.

- ABECEDAR Primer printed in Athens for use by Macedonian school children in Aegean Macedonia. Written in Latin alphabet and reflects the Macedonian language spoken in Bitola-Lerin (Florina) district in Western Aegean Macedonia.

- Serbs and Bulgarians protest to League of Nations. Primer undermines their claim that Macedonians are Serbs and Bulgarians respectively.

- Greece counters with last minute cable to League: “the population…..knows neither the Serbian nor the Bulgarian language and speaks nothing but a Slav-Macedonian idiom.”

- Greece “retreats” so as to preserve Balkan alliances. Primer is destroyed after League of Nations delegates leave Salonika (Solun). Thereafter, Greece denies existence of Macedonians. Refers to Macedonians as “Slavophone Greeks”, “Old Bulgarians” and many other appellations but not as Macedonians.

1926 – Legislative Orders in Government Gazette #331 orders Macedonian names of towns, villages, mountains changed to Greek names.

1927 – Cyrillic inscriptions ( Macedonian alphabet) in churches, tombstones and icons rewritten or destroyed. Church services in the Macedonian language are outlawed.

- Macedonians ordered to abandon personal names and under Duress adopt Greek names assigned to them by the Greek state.

1928 – 1,497 Macedonian place names in Aegean Macedonia Greekized since 1926.

- English Journalist V. Hild reveals, “The Greeks do not only persecute living Macedonians., but they even persecute dead ones. They do not leave them in peace even in the graves. They erase the Macedonian inscriptions on the headstones, remove the bones and burn them.”

- Macedonian Place Names Changed – Click to View file

1929 – Greek Government enacts law where any demands for national rights for Macedonians are regarded as high treason.

- LAW 4096 directive on renaming Macedonian place names.

1936-1940 – During Ioannis Metaxas’s dictatorship, the Macedonian language was legally banned, with violators facing fines or harsher punishments, including exile, imprisonment, and physical abuse. This prohibition extended beyond public settings, applying even to private use of the language at home.

In Aegean Macedonia, including the village of Zelenich, there are numerous accounts of southern Greek police officers spying on Macedonians by hiding outside windows to monitor the language spoken inside private homes. Residents were fined or imprisoned if they couldn’t pay the fines. In one notable case, a grandfather was taken to court for using Macedonian with his donkey; he had told the animal to stop by saying, “Tsoux.”

1944-1949 – In recent history, there was a brief period when the use of Macedonian was not only permitted but encouraged: during the Greek Civil War, in areas controlled by left-wing resistance and guerrilla groups. During this time, Macedonian-language newspapers were published, schools were established, and teacher-training courses were organized to support these schools. Although short-lived, this period significantly contributed to the language’s survival. Many people now in their eighties remember attending these schools and are still able to read Macedonian texts in the Cyrillic script.

1950s – The authoritarian regimes governing Greece after the Civil War enacted various measures to suppress the use of the Macedonian language. Entire villages were compelled to take “language oaths,” in which residents publicly pledged never to speak their language again. In schools, teachers not only forbade students from speaking Macedonian but also implemented intricate reporting systems, pressuring students to report classmates—and even family members—they heard using the language in private.

During this period, Greek authorities implemented one of their most effective assimilation strategies by establishing kindergartens and nursery schools in nearly every Macedonian village, aiming to ensure children learned Greek from an early age. Mandatory evening schools were also introduced for older villagers, providing them with basic instruction in Greek. In Zelenich even grandparents especially grandmothers were forced to learn Greek and if they refused, they were threatened with hefty fines which most were not able to afford.

1970s – Another partially successful measure offered scholarships to top students after primary school, allowing them to attend specialized boarding schools in southern Greece. These initiatives greatly increased fluency in Greek and consequently reduced the use of Macedonian within families.

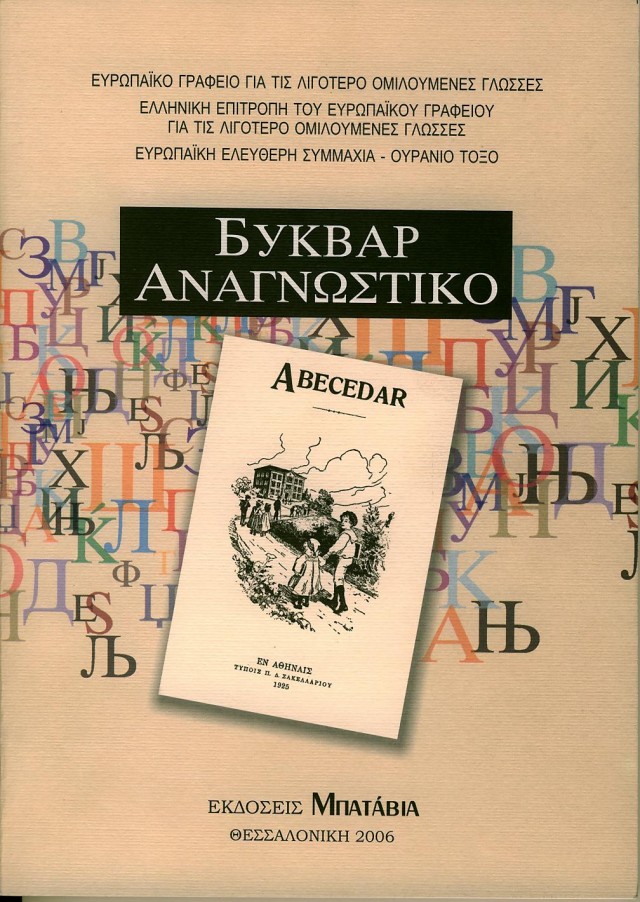

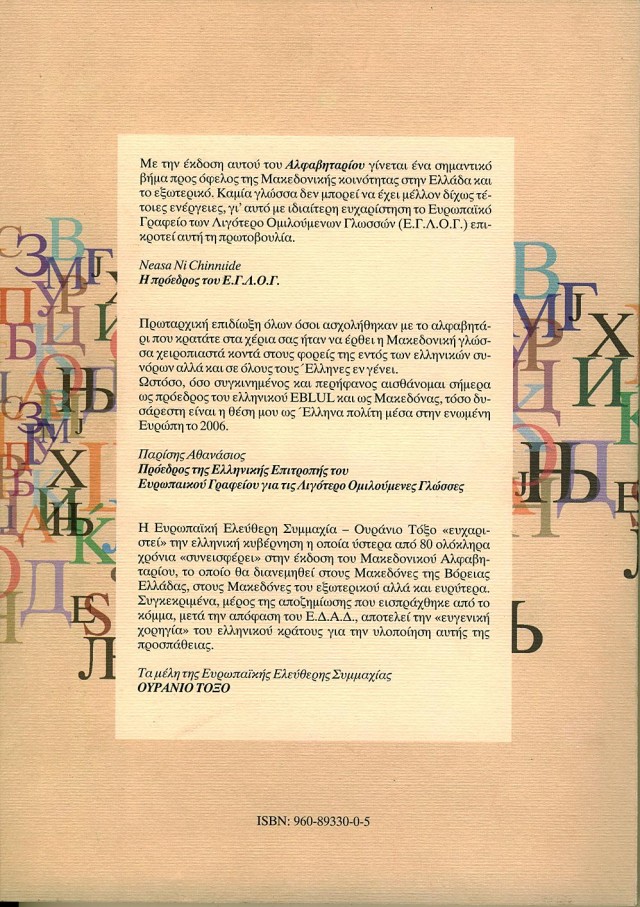

Macedonian Abecedar re-published in Greece after 81 years (Oct. 12, 2006)

The Abecedar is a fascinating historical artifact, reflecting the complex dynamics of identity, language, and politics in the Balkans. Published in 1925 in Athens, it aimed to provide basic Macedonian language education to children of Macedonian heritage living in Greece. This initiative emerged following the Treaty of Lausanne (1923) and subsequent efforts to address minority rights in the aftermath of World War I.

Although the Abecedar was an acknowledgement of the existence of a Macedonian minority in northern Greece, its use and distribution were controversial. Political pressures and opposition from Greek nationalists meant that it was never fully implemented or widely distributed. Moreover, the book used the Latin script instead of the Cyrillic script traditionally associated with the Macedonian language, further complicating its acceptance by the intended community.

The republication of the Abecedar after 81 years is a significant gesture, symbolizing a renewed interest in historical reconciliation and the acknowledgement of linguistic and cultural diversity in Greece. It also serves as a reminder of the unresolved debates surrounding identity and minority rights in the region, which remain sensitive to this day. Source: EFA-EPP Rainbow – Political Party of the Macedonian Minority in Greece

(Member of the European Free Alliance – European Political Party (EFA-EPP))

The new edition of the primer is comprised of two parts:

The first part is an identical copy of the Abecedar from 1925 that was targeted at the Macedonian population in North Greece. The second part of this issue contains a modern primer of the contemporary Macedonian language, as it is studied all around the world. The primer has already been distributed in Greece. The Abecedar of 1925 is a historically significant text that represents a rare acknowledgement of the linguistic and cultural identity of the Macedonian-speaking population in northern Greece. Here’s a detailed breakdown of the context:

Historical Context:

1. League of Nations and Minority Rights: After World War I, the League of Nations championed the protection of minority rights as part of peace treaties with several European nations, including Greece. This included the assurance of education and linguistic rights for minority populations within member states.

2. Macedonian Population in Greece: Northern Greece, particularly the regions of Florina (Lerin) and Kastoria (Kostur), was home to a significant population that spoke Slavic dialects. These people self-identified as Macedonian. However, their cultural and linguistic identity was often suppressed by Greek authorities, especially during periods of heightened nationalism.

3. Publication of the Abecedar: Responding to pressure from the League of Nations, the Greek government reluctantly produced the Abecedar in 1925. It was intended to provide elementary education in the Macedonian language. Notably, the primer was written using the Latin script rather than Cyrillic, likely to avoid associating it with Bulgarian or Serbian orthographies, as tensions over the Macedonian region were intense among neighbouring Balkan states.

4. Confiscation and Destruction: Despite its publication, the Abecedar was never distributed to Macedonian-speaking children. The Greek authorities, facing internal nationalist opposition and international scrutiny, confiscated and destroyed the primer soon after it was printed. This marked another episode of the suppression of minority languages and identities in Greece.

Modern Reprinting and the Role of Rainbow:

1. Rainbow Political Party: Established in the 1990s, Rainbow (Vinozhito) is a political organization representing the Macedonian minority in Greece. It advocates for cultural, linguistic, and political rights, including the recognition of the Macedonian language and identity.

2. Reprinting the Abecedar: In the 1990s, Rainbow reprinted the Abecedar, contextualizing it within a broader movement for minority rights. This reprint included historical documentation, contemporary commentary, and multilingual translations (Greek, Macedonian, and English) to highlight the historical neglect and ongoing challenges faced by the Macedonian-speaking community in Greece.

3. European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) Victory: In 1995, Rainbow won a landmark case at the ECHR after a bilingual Macedonian-Greek signboard in Florina (Lerin) was destroyed by vandals. The ruling favoured Rainbow, emphasizing freedom of expression and minority rights. Funds from this legal victory helped finance the reprinting of the Abecedar.

Significance of the Abecedar Today:

1. Symbol of Suppressed Identity: The primer has become a symbol of the historical suppression of the Macedonian language and culture in Greece. Its reprinting serves as both a reminder of past injustices and a call for greater cultural recognition and minority rights in the present.

2. Cultural Preservation: By reintroducing the Abecedar, Rainbow and other activists aim to preserve the Macedonian language and raise awareness about the cultural heritage of Macedonian speakers in northern Greece.

3. International Advocacy: The inclusion of Greek, Macedonian, and English in the reprinted primer reflects efforts to build bridges between communities and to internationalize the discourse around minority rights in Greece.

The linguistic features of the Abecedar:

1. Language and Dialect Choice: The Abecedar was intended for the Macedonian-speaking population in Greece. However, rather than employing the Cyrillic script traditionally used for Slavic languages in the Balkans, the Abecedar used a Latin script to represent the spoken language. This decision was likely influenced by political considerations:

• Avoidance of Cyrillic Script: Greece sought to dissociate its Macedonian-speaking population from Bulgarian or Serbian influences, as these neighbouring states had vested interests in the contested Macedonian region.

• Phonetic Representation: The primer’s language was based on the spoken dialects of the region, which were closer to Macedonian Slavic vernacular than standard literary Macedonian. This suggests an effort to directly appeal to the population’s everyday linguistic practices while avoiding affiliations with any formalized national language.

2. Alphabet and Phonetics: The Latin script used in the Abecedar was adapted to suit the phonetic characteristics of the Macedonian dialects spoken in northern Greece:

• Innovative Orthography: The primer employed a phonetic approach, with letters chosen to approximate the sounds of the Macedonian language as closely as possible within the constraints of the Latin alphabet.

• Simplification for Beginners: As a primer, the Abecedar was designed to teach basic reading and writing skills. Its orthographic choices prioritized simplicity and clarity for young learners.

3. Text Content and Vocabulary: The Abecedar focused on basic vocabulary and practical language use, reflecting its purpose as a tool for elementary education:

• Everyday Words and Phrases: Lessons included terms related to daily life, nature, family, and community—elements that were accessible and relatable to children.

• Cultural Neutrality: The content avoided political or nationalistic references, likely to reduce controversy in a politically sensitive context. The focus was on education rather than fostering a specific national identity.

4. Multilingual Considerations: Although the original Abecedar was primarily in Macedonian (written in the Latin script), it reflected a broader multilingual environment:

• Greek Language Context: The primer was created within Greece, where Greek was the official language. Despite this, the Abecedar made no significant efforts to integrate Greek into its linguistic content, reflecting its minority-oriented purpose.

• Reprinted Versions: Modern reprints of the Abecedar include translations into Greek and English, making the primer more accessible to broader audiences and emphasizing its historical and cultural significance.

5. Political Impact on Linguistic Choices; The linguistic features of the Abecedar underscore its role as a political document:

• Identity Suppression: The use of Latin script and avoidance of Cyrillic can be seen as an attempt to de-emphasize the cultural and national identity of Macedonian speakers, aligning with Greek efforts to assimilate or marginalize minority groups.

• Regional Dialects: By basing the language on local dialects rather than a standardized form of Macedonian, the primer reflects both the fluid linguistic landscape of the region and the Greek government’s desire to avoid validating Macedonian as a distinct national language.

6. Legacy of Linguistic Features: The linguistic approach of the Abecedar continues to provoke interest and debate:

• Symbol of Linguistic Rights: The primer’s focus on Macedonian dialects highlights the historical struggle for linguistic recognition among minority communities in Greece.

• Critique of Orthographic Choices: Some scholars have criticized the Latin script as an artificial imposition, while others view it as a pragmatic solution to the political constraints of the time.

• Reclamation by Activists: Modern reprints emphasize the historical and cultural importance of the primer’s linguistic content, celebrating it as a step toward the recognition of the Macedonian language in Greece.

Modern Primer of Macedonian Language

1. Content and Purpose:

• The modern primer introduces the contemporary Macedonian language, reflecting its standardized form as developed in the mid-20th century.

• It aims to provide Macedonian speakers in Greece with an accessible resource for learning their native language, reconnecting them with their linguistic heritage.

2. Global Context:

• Unlike the 1925 Abecedar, which focused on regional dialects, this primer represents the modern, standardized Macedonian language used globally, reinforcing its status as a distinct Slavic language recognized by linguists and institutions worldwide.

3. Distribution and Promotion:

• The primer has already been distributed in areas of Greece with Macedonian-speaking populations, particularly in northern regions like Florina (Lerin), Kastoria (Kostur), and Edessa (Voden).

• Promotional events in major Greek cities, including Athens and Thessalonica, highlight the growing push for public recognition of the Macedonian language within Greece.

Significance of the Modern Primer

1. Cultural Reclamation:

• The modern primer is not just an educational tool but a symbol of the ongoing struggle for identity and recognition. For Macedonian speakers in Greece, it represents a step toward preserving their linguistic and cultural heritage.

2. European Advocacy:

• The involvement of the EFA signals growing international support for the rights of minorities in Greece, placing pressure on the Greek government to address these issues.

3. Catalyst for Dialogue:

• By promoting the primer and engaging Greek communities, advocates hope to foster dialogue and reduce the historical mistrust between Macedonian-speaking populations and the Greek state.

Today, while the Macedonian language is no longer officially forbidden, it remains barely tolerated. In recent years, many articles have appeared in the press dismissing the language as “non-existent” or describing it as a hybrid mish-mash of Greek and foreign words. Schoolteachers still advise students not to speak “that gypsy-Skopjan language.” Unfortunately, misunderstandings persist, with some Greeks ignorantly referring to the Macedonian language as Bulgarian..

In the cultural sphere, conflicts still arise annually over the right to sing song lyrics in Macedonian at village festivals. As of 2024, during our visit to festivals in Western Macedonia, only Sklithro (Zelenich) refrained from including lyrics in songs. Indigenous Macedonians in Sklithro-Zelenich continue to face threats from non-Macedonian residents in the village. While the melodies of traditional songs are played, the lyrics are omitted—despite the fact that every other village in the area includes Macedonian lyrics in these centuries-old songs.

EVIDENCE OF MACEDONIAN LANGUAGE PRIOR TO ABECEDAR

Gianelli’s 16 Century Macedonian Lexicon Found at the Vatican

In the late 1940s, a 16th-century lexicon was discovered at the Archivum Secretum Vaticanum, the secret Vatican Library. Initially believed to be written in Greek due to its use of the Greek alphabet, the lexicon could not be deciphered using Greek. Upon further examination and reading, it was revealed that the language was actually Macedonian, specifically relating to the Old Kostur Dialect from Aegean Macedonia. This discovery provided significant evidence of the Macedonian language’s historical roots and its distinct identity within the South Slavic linguistic group.

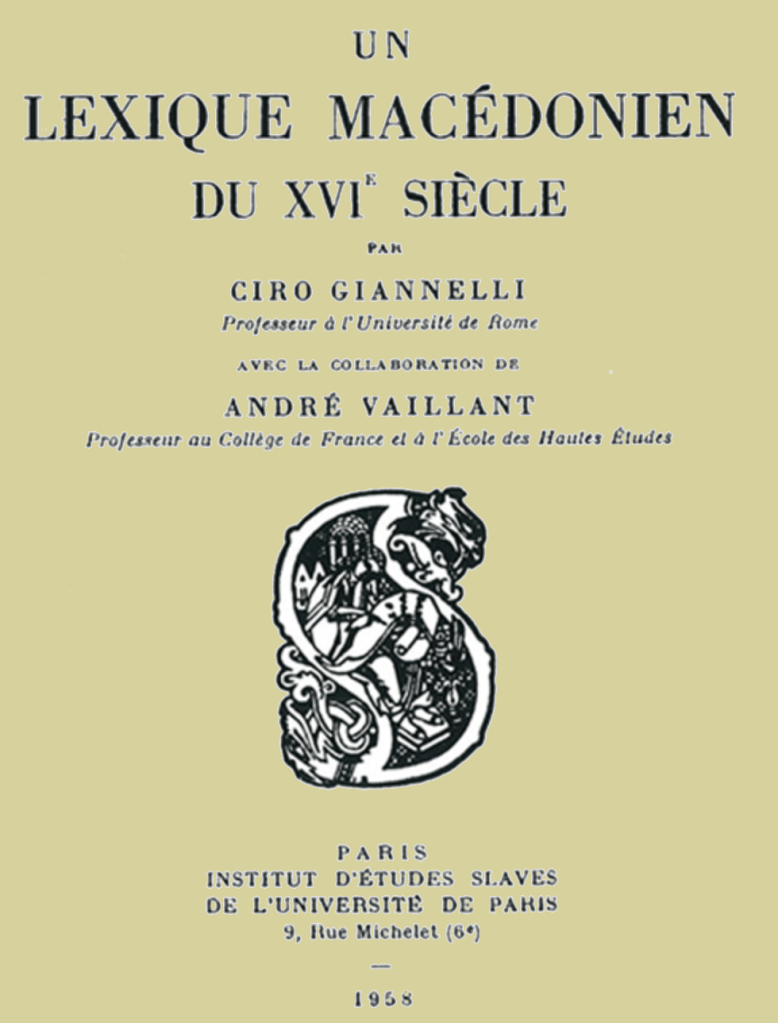

The dictionary has a long history that spans several centuries, originating in the 16th century and continuing to be recognized and studied well into the 20th century. It was later published by Professor Giannelli of Rome in collaboration with Andre Vaillant, a professor at the University of Paris, who provided a linguistic analysis of the dictionary. Vaillant’s scholarly work contributed to the understanding of the dictionary’s linguistic significance, highlighting its importance as a historical document that sheds light on the Macedonian language and its regional variations, particularly the Kostur dialect.

The great importance of Ciro Giannelli’s dictionary lies in its role as a document that highlights the unique characteristics of the Macedonian language in relation to its neighbouring South Slavic languages, Serbian and Bulgarian. This dictionary serves as evidence of the distinctiveness of Macedonian, a uniqueness that has been preserved for nearly five centuries. Through its content, it offers valuable insights into the linguistic identity of the Macedonian people, underscoring the enduring differences that set it apart from other regional languages.

Giannelli’s dictionary is a bilingual, dialectal dictionary, with Macedonian terms explained in Greek. It features an explicative character, as broader explanations follow some of the lexical entries, even though the dictionary is somewhat irregular in its structure. The dictionary contains more than 300 folk words specific to the Kostur Region dialect, covering a wide range of categories such as household items, food, family relationships, parts of the human body, agricultural terms, religion, and more. This collection provides valuable insight into the local vernacular and culture of the region, further emphasizing the distinctiveness of the Macedonian language.

The various dialects of Macedonia are generally grouped into three main categories. The first two are the basic east and west dialects, which are divided by the Vardar River. The third dialect encompasses the Kastoria (Kostur), Florina (Lerin), Tikvesh, and Mariovo, regions, and is referred to as a transitional dialect because it contains features of both the eastern and western dialects. These dialects reflect the linguistic diversity within Macedonia and the complex historical and geographical factors that have influenced the development of the Macedonian language.

Download Gianelli’s XVI-Century Lexicon

Download Notes on Lecture given on the Lexicon by professor Joseph Schallert a Slavic linguist from the University of Toronto and professor Kosta Peev (author of Lexicon of Macedonian Dialects of SE Aegean Macedonia).

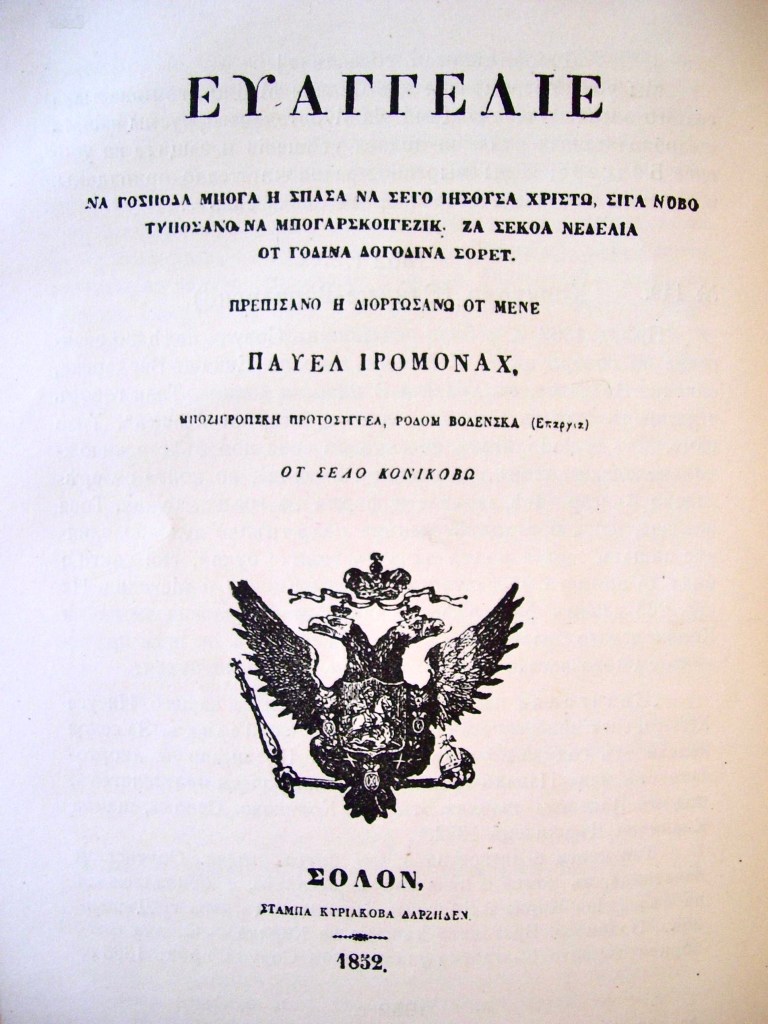

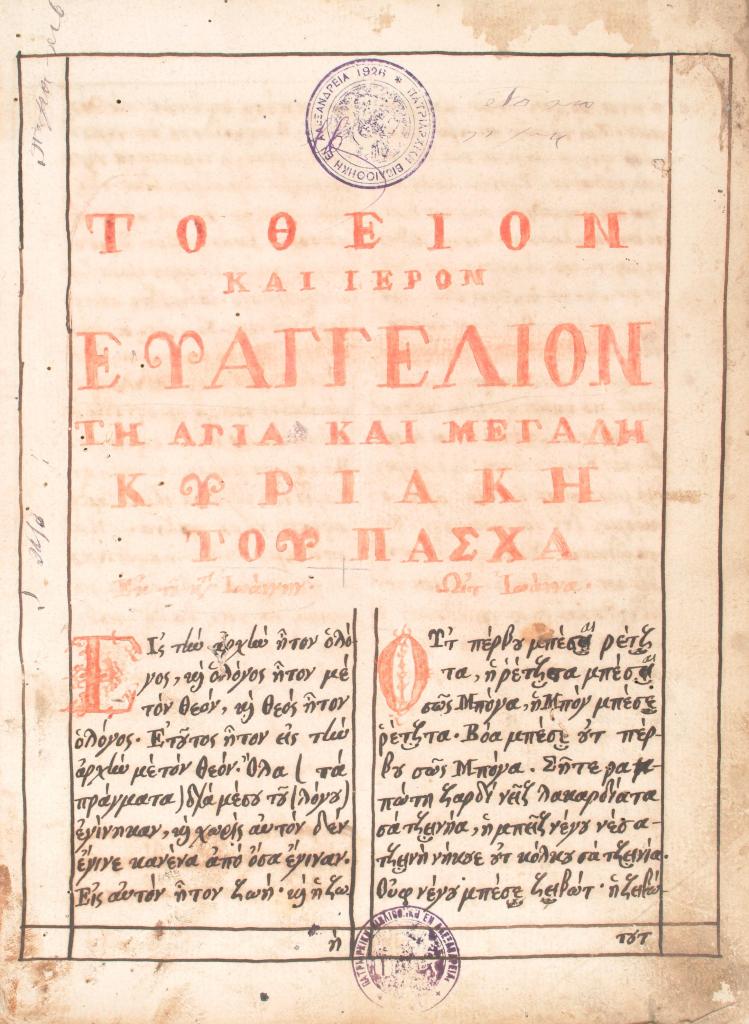

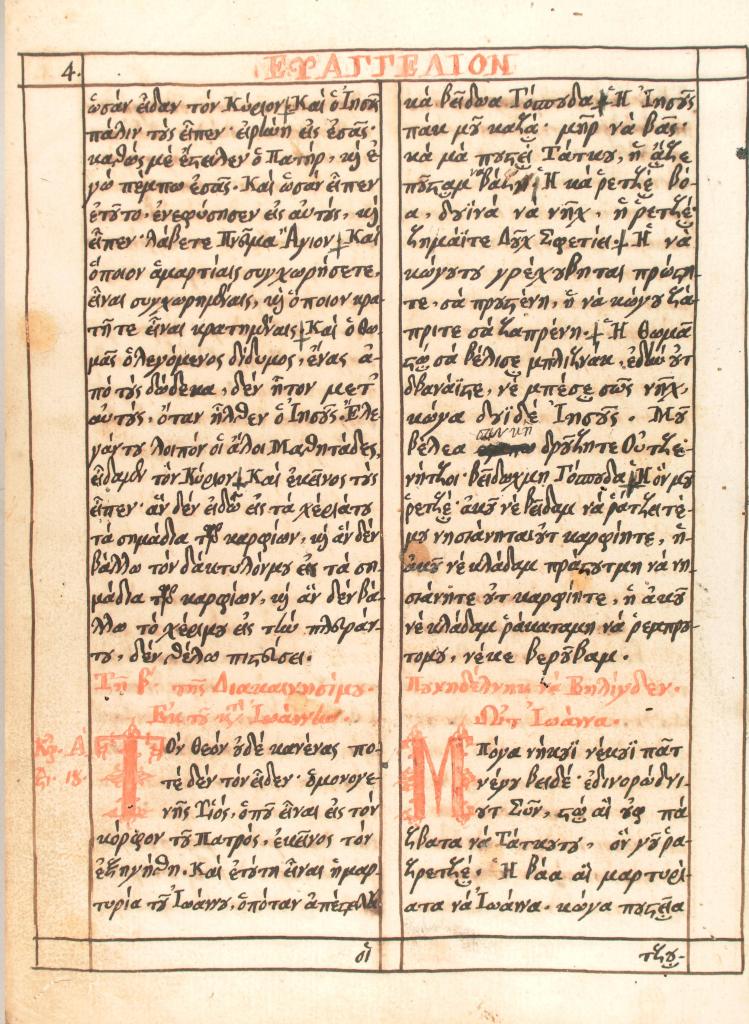

“Rediscovery of the Konikovo Gospel: A Lost 18th-Century Macedonian Translation”

This text represents a New Testament translation into the Macedonian language, specifically in the dialect of Lower Vardar, a region encompassing the areas between Voden (Gr. Έδεσσα), Kukush (Gr. Κιλκίς), Solun (Gr. Θεσσαλονίκη), and Ber (Gr. Βέροιας). Dating back to the late 18th century, the manuscript was lost for over a century until its rediscovery in 2003 by Finnish historian and philologist Mika Hakkarainen in the library of the Greek-Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria. Jouko Lindstedt later identified the manuscript as the so-called Konikovo Evangelie and undertook its transliteration.

Since its rediscovery in the Patriarchal Library of Alexandria in 2003, the Konikovo Gospel has become the focus of intensive study by a team of Finnish and Macedonian scholars, led respectively by Jouko Lindstedt and Ljúdmil Spasov, with contributions from American Balkanist Victor Friedman. Although Lindstedt brought the manuscript’s history and potential significance to the attention of the academic community in 2006, much of the collaborative research conducted on this remarkable text remains unpublished.

The book explores a wide array of topics, including the authorship, purpose, graphemics, phonology, morphology, lexicon, dialectal features, and cultural-historical significance of the Konikovo Gospel. While written in Greek script, the text is notable as “the oldest known text of greater scope that directly reflects the living Slavic dialects of what is today Greek Macedonia.” Furthermore, it stands as the earliest known Gospel translation in what we now identify as Modern Macedonian.

As such, the Konikovo Gospel is a document of significant importance to the history of the Macedonian language. The publication is a valuable resource not only for specialists in this field but also for scholars interested in Balkan Slavic dialectology, Greco-Macedonian translation practices, the representation of Balkan Slavic languages using Greek orthography, and the production of vernacular Gospels—both Greek and Slavic—across the Balkans.

The Road to Konikovo: Thoughts on the Context and Ethics of Philology -Jouko Lindstedt (University of Helsinki) – Click on Title to download PDF

“19th Century Macedonian Treasures: Two Notable Volumes at the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library”

This article, originally published in The Halcyon, the newsletter of the Friends of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, was written by Christina E. Kramer from the Department of Slavic Languages and Literature. It highlights two significant Macedonian works now housed in the University of Toronto’s collection.

In 2001, the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library and Robarts Library at the University of Toronto acquired nearly 300 volumes from the Macedonian Collection of Horace G. Lunt, Professor Emeritus of Slavic Linguistics at Harvard University. This invaluable collection includes rare journals from the 1940s and 1950s, along with numerous first editions by prominent Macedonian novelists, poets, and folklorists of the 20th century.

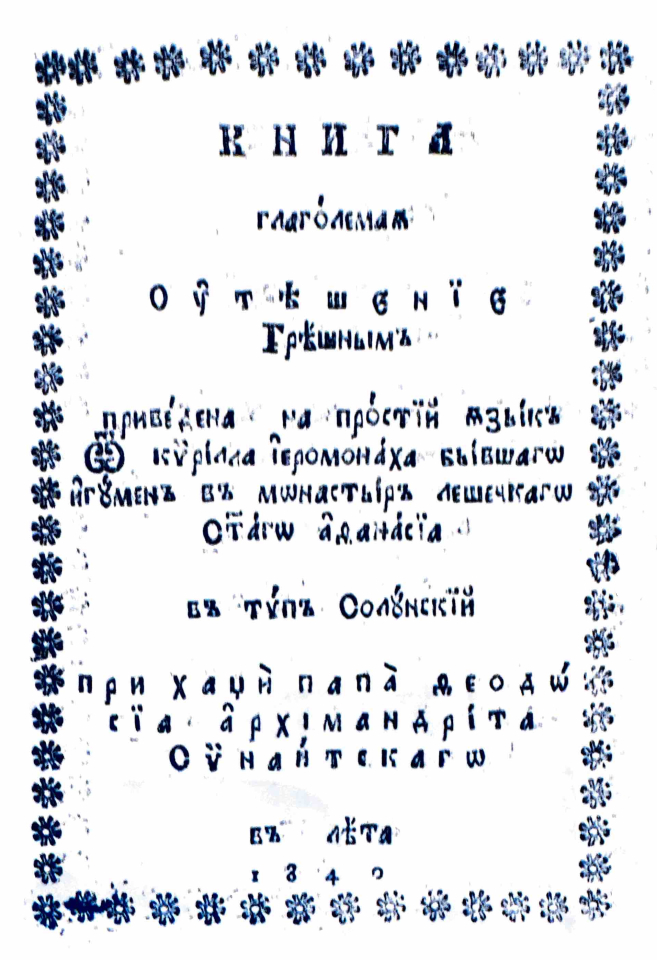

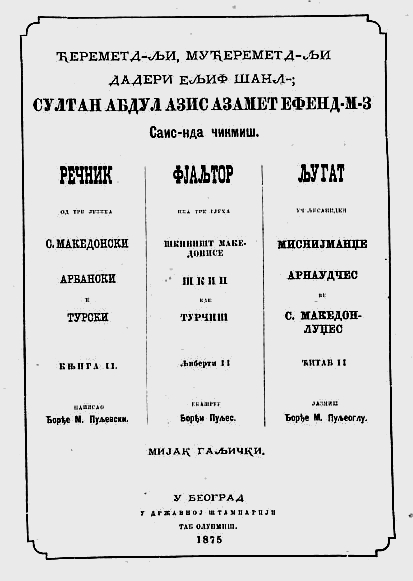

Among the collection’s highlights are two particularly significant 19th-century volumes: Utešenie grešnim (“Comfort to Sinners”) by Kiril Pejčinovik, a book of teachings and prayers published in Salonika in 1840, and Rečnik od tri jezika (“Three Language Dictionary”) by Gjorgji Pulevski, published in Belgrade in 1875. These works represent foundational texts in Macedonian literature and linguistic heritage.

These two works hold particular importance for both the development of the modern Macedonian standard language and the documentation of early Macedonian national consciousness.

To understand the historical significance of these works, it’s essential to recognize that in the early 19th century, South Slavic languages were undergoing standardization amid the emergence of new nation-states in Southeast Europe, carved from territories of the Ottoman Empire.