Forgiveness is a great holiday for the Macedonian people and it is associated with many customs and beliefs. It is obvious that forgiveness is a custom established under the influence of the church, while its fires, divinations, and carnivals are remnants of pre-Christian spring parties.

The tradition of “Forgiveness Sunday – Prochka is no longer followed in the village of Sklithro-Zelenich. This Macedonian custom disappeared as a result of pressure and assimilation policies of the Greek state and Greek Orthodox church. But, various aspects of “Prochka” are still followed in some towns and cities in Greece. They are fully celebrated in the Republic of Macedonia where this tradition has survived and flourished.

Villagers celebrated the feast of Prochka, which took place on the Sunday before “Clean Monday” – the start of Lent. With Prochka begins the long (seven weeks) Easter fasting period filled with many customs and beliefs, to welcome Christ’s resurrection at Easter.

It was believed that on this day heaven and earth forgive each other, so people should do the same.

Forgiveness begins with the long Easter fasts, a period filled with many customs and beliefs, with many denials and hopes for the reception of Christ’s resurrection (Easter) for communion and identification with the Savior Jesus Christ. Rich customs are performed on Forgiveness, such as forgiveness (hence the name of the holiday), followed by amkanje, ritual fires, rich tables, divination for life and happiness, customs for cleaning from fleas, lice and other pests.

The custom of forgiveness starts from the Christian understanding of helping and forgiving people. People ask for forgiveness from one another for their mistakes. Usually, the younger ask for forgiveness from the older, children from parents, baptized from their “Cum” or godparent, and friends, relatives, and neighbours are also forgiven.

On Prochka in the village, daughters and sons would ask their parent’s for forgiveness for anything they would have done wrong against them. They would bow three times before the elder, kiss their hand and say, “Forgive me” (da ma prostis). To which the elder would respond, “You are forgiven from me and the Lord, or just “You are forgiven.” They then attend Sunday mass and receive communion.

Due to the fact that people in the village and region no longer follow this tradition, we can only report on oral history stories that have been passed on from our parents and grandparents. But, in the Republic of Macedonia, Prochka is alive and well. It has survived and evolved into a modern type of Balkan Mardi Gras. The carnival in Prilep is impressive for the authentic bear masks, which continue the centuries-old tradition of celebrating the butchers of this city. The Feast of Forgiveness is a great holiday for the Macedonian people and it is associated with rich customs and beliefs. It is obvious that forgiveness is a custom established under the influence of the church, and parties, such as those around bonfires, fortune-telling, carnivals and the like are remnants of pre-Christian spring parties.

FORGIVENESS – Prochka and its Pagan Rituals

During Prochka (Forgiveness Sunday) the custom of asking for forgiveness, was also tied to the special ritual with eggs called ‘amkanje.’ Amkanje was a custom held on the evening of Prochka, when the family would gather at home. The custom is practised so that the unpeeled boiled egg is attached with hemp thread and hang on a wand or a rolling pin. Then children sit at the table and knelt on their knees, and an adult brings the egg closer to the mouth of each child and the child shouts “am, am” and attempts to catch the egg with his/her mouth.

Prochka is a holiday that is celebrated seven weeks before Easter and has a mobile date. It happens that the celebration occurs before Lent. The rituals that are performed on this day are related to spring, in spite the Christian elements that are added to it. This is the last day before Easter when oily food is eaten. The next day the big Easter fast begins with “Clean Monday.”

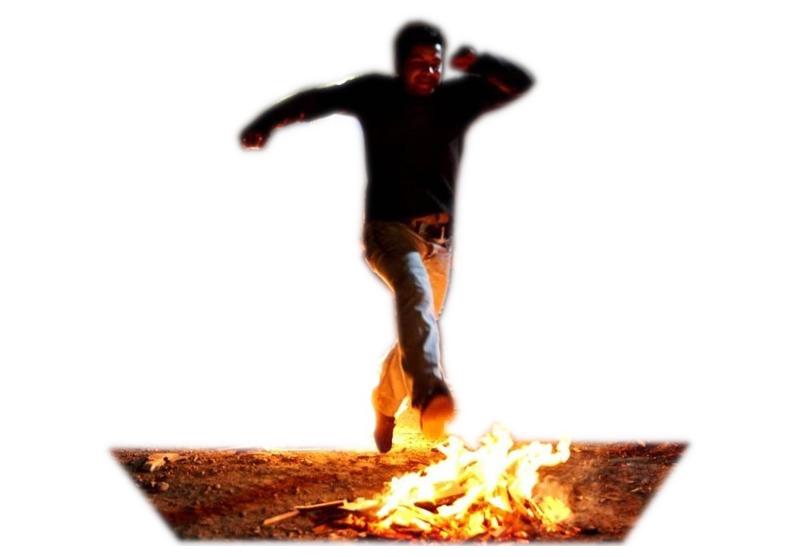

These celebrations include many elements from the pre-Christian period, and the rituals are not related to Christian teachings. The night before Prochka each neighbourhood makes a “koliba” (pile of braches) using willow branches and straw around one meter high. The pile is burned, people dance around it and when the fire calms down everyone jumps over it. As a child growing up in the village, I remember jumping over the fire and having smudged ashes and blacken our faces.

At the end of the 19th century in the villages of Embore, Debreć and Palior (Emporion, in the Aegean part of Macedonia, children also made a large pile of wood, spruce and straw, called Erle, and lit it on the evening of the holiday by firing a rifle or a pistol. If that did not work, they set it on fire. They sang around the fire and then carried a burning bundle of straw (rye) home, believing that there would be no fleas in the summer. This is how the children from every neighborhood made Erle and competed with whose fire would burn the longest. The celebrations including fires are known to all European people, and their origin dates long before Christianity. The dancing around the ritual fire is a “magical cyclical movement” that aims to establish a magical connection between the object and the participants of the ritual, so that they gain a part of the power that the object has, in this case the fire.

The custom of kindling bonfires on the first Sunday in Lent and jumping over the fire is done for: health, and for protection against diseases, since fire has healing and purgative power. This is why everyone wanted to jump over the fire. These rituals are part of the common rituals of the whole village, but besides them there were rituals for health performed at home.

At Prochka the family performs the ritual “amkanje” of an egg, known to all Macedonians. It is done in the evening, when everyone gathered for dinner, a long wool thread was tied to a wand and an egg at its end. All members of the family tried to catch it only using their mouth, not their hands. The one that succeeded in doing this would be healthy the whole year round.

Everyone had a piece of the egg and the thread that tied the egg to a wand was used for predicting through magical tying. A part of the thread would be tied in knots. Then each of the knots had its protective function, and its function was pronounced aloud so that everyone could hear it: to tie the mouths of the snakes, and then the thread was burned; to tie the mouths of the enemies, and then the thread was burned; to tie the mouths of the wolfs, the bears and the foxes, and again a knot. The procedure was repeated until the last knot would burn, and then it was kept for putting spells.

Everyone drank some water from the eggs crust, and in the morning threw it in water, at the well, while they got water in “bukarinja” (wooden cask or bowl of water), as this water had a healing, regeneration power that chased bad, dirty forces.

Another custom of throwing missiles into the air prevails in many parts of Western Europe. Identical customs are observed in several Slavonic countries. In all these cases the pagan survival of the bonfires are built by boys on the crests of mountains and hills as in Macedonia. The children amuse themselves by shooting with bows and arrows, a custom which… is supposed to have referred in older times to the victory obtained by the sunbeams the arrows of the far-darting Apollo over the forces of cold and darkness.

Apart from any symbolical or ritual significance which may or may not lurk in the practice, the use of the sling and the bow by the Macedonian boys at play is instructive as a conspicuous instance of a custom outliving in the form of a game the serious business of which it originally was only an imitation. Toy bows and slings are extremely popular among boys all over Europe at certain times of the year, and keeping up, as they do, the memory of a warlike art now extinct, are regarded by ethnologists as sportive survivals of ancient culture, if not of ancient cult.

Women and Procha

Women, for some reason or other, take with them a cake as a propitiatory offering to those on whom they call. On the mid Sunday of Lent it was the custom to go a-mothering, that is to pay a formal visit to one’s parents, especially the female one, and to take to them some slight gift, such as a cake or a trinket. Hence the day itself was named also Mothering Sunday.

At supper-time a tripod is set near the hearth, or in the middle of the room, and upon it is placed a wooden or copper tray. Round the table thus extemporized sit the members of the family cross-legged, with the chief of the household at the head. The repast is as sumptuous as befits the eve of a long fast, and a cake forms one of the most conspicuous items on the menu. Before they commence eating the younger members of the family kneel to their elders and obtain absolution, after which performance the banquet begins.

When the plates are removed there follows an amusing game called ‘amkaje’ and corresponding to the the Celtic festival Samhain, of “Bobbing for Apples” at Halloween time, which was a Gaelic celebration that marked the end of harvest season and the beginning of winter. Similarly, the Macedonian game of ‘amkaje’ corresponds with the end of winter and the birth of spring. A long thread is tied to the end of a stick or the ceiling, and from it is suspended a bit of confectionery, or a boiled egg. The person that holds it bobs it towards the others who sit in a ring, with their mouths wide open, trying to catch the morsel by turns. Their struggles and failures naturally cause much jollity and the game soon gets exciting. This amusement is succeeded by songs sung round the table and sometimes by dancing.

A quaint superstition attached to the proceedings of this evening deserves mention. If anyone of those present happens to sneeze, it is imperative that he/she should tear a bit off the front of his/her shirt, in order to ward off evil influences. When one sneezes, those around that individual are to assist in warding off evil influences by replying, “Zdrafche, Zifche, Bache Ghus” (health, life, kiss butt).

Clean Monday

The days that follow form a sharp contrast to this feast. The next day begins “Clean Monday.” A period of purification both of body and of soul. The cooking utensils are washed and polished, the floors are scrubbed.

“All traces of the preceding rejoicings are scrupulously effaced, and the peasant household assumes an unwonted look of puritanical austerity. The gloom is deepened by the total abstention from meat and drink, which is attempted by many and accomplished by a few during the first three days of the week.”

This period of rigid and uncompromising fast, is concluded on Wednesday evening. Then a truly Lenten pie of boiled cabbages and pounded walnuts, is solemnly eaten and, undoubtedly, relished by those who succeeded in going through the three days’ starvation.

For Roman Catholics and other Western Christians Lent, a period of spiritual preparation for Easter, begins with an observance called Ash Wednesday and lasts a little over six weeks. For Eastern, or Orthodox, Christians, lent lasts a full seven weeks and begins on the evening of Forgiveness Sunday. Orthodoxy is one of the three main branches of the Christian faith. Orthodox Christianity developed in eastern Europe and the countries surrounding the eastern half of the Mediterranean Sea. Orthodox Christians follow a different church calendar than that commonly adhered to by Roman Catholics and Protestants.

Forgiveness Sunday falls on the seventh Sunday before Orthodox Easter. On this day church services recall the story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Paradise. The Gospel reading (a selection from Christian scripture describing the life of Christ) presents Jesus’ teaching on forgiveness and fasting (Matthew 6:14-18). The name “Forgiveness Sunday” comes from the Gospel reading and also from the custom of forgiving others and asking for others’ forgiveness on this day. By practising forgiveness with one another, Orthodox Christians hope to invite God’s forgiveness and to begin Lent with the proper spirit of humility. Some Orthodox parishes, monasteries, and schools follow a formal ritual of forgiveness after the Sunday evening worship service. Members of the community bow to one another, ask forgiveness for their offences, and offer forgiveness to each other.

Forgiveness Sunday is also called Cheese Sunday since it is the last day on which strictly observant Orthodox Christians eat milk, cheese, and other dairy products before the beginning of the full-fledged Lenten fast. Cheesefare, or Forgiveness Sunday marks the end of Cheese Week. This, the first week of the Lenten fast, is only partial. Meat products are forbidden during this week, but dairy products may still be eaten. The full Lenten fast begins on Forgiveness Sunday, after the evening, or vespers, service. Some Orthodox Christians exchange the greeting “May your fast be light” as a means of expressing well wishes at this holy time of year. For the next seven weeks strictly, observant Orthodox Christians will consume no meat, eggs, dairy products, olive oil, fish, wine, or alcohol. The following day, known as Clean Monday, constitutes the first full day of Lent.

The folk customs of Cheese Week and Forgiveness Sunday anticipate the upcoming fast and the solemnity of Lent by encouraging indulgence in what soon will be forbidden. For example, folk tradition encourages people to feast on egg and cheese dishes. Also, since Forgiveness Sunday constitutes the last day of Carnival for Orthodox Christians, people enjoy dances, masquerades, and other frolics. In Greece, a predominately Orthodox country, people also treat the following day, Clean Monday, as a joyous occasion.

Symbolism of the Egg

Some of the Orthodox folk customs concerning Cheese Week and Forgiveness Sunday feature eggs, an Easter symbol and forbidden food during the Lenten season. Many follow an old Greek tradition which dictates that the last bit of food consumed before the beginning of the fast be a hard-boiled egg. Before eating the egg one declares, “With an egg I close my mouth, with an egg I shall open it again.” For those who observe this custom the eating of an egg symbolizes both the beginning and the end of the seven-week Lenten fast. After the late-night Easter Vigil service on Holy Saturday, they begin their Easter feast with a hard-boiled Easter egg.

Sources:

Abbott, G. F. (2011). Macedonian folklore. Cambridge University Press.

Forgiveness Sunday. (n.d.) Encyclopedia of Easter, Carnival, and Lent, 1st ed.. (2002). Retrieved March 18 2021 from https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Forgiveness+Sunday

Forgiveness Sunday. (n.d.) Holiday Symbols and Customs, 4th ed.. (2009). Retrieved March 18 2021 from https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Forgiveness+Sunday

Frazer, J. G. (1890). The golden bough. The Golden Bough, 323-324. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139207539.014

Heath-Eves, S. (2019, March 20). Jumping over fire, and other ways to celebrate Persian new year. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/fire-jumping-nowruz-persian-new-year-1.5064462

INFO, P. (n.d.). Carnival Prochka – Forgiveness. PRILEP INFO. https://www.prilepinfo.mk/en/cultural-events/carnival-prochka-forgiveness

Info@fakulteti.mk, F. -. (n.d.). Што е значењето на Прочка и како се празнува? fakulteti.mk. https://www.fakulteti.mk/news/14032021/shto-e-znachenjeto-na-prochka-i-kako-se-praznuva

Kalantari, S. (2014, March 21). Fire-jumping and eating ‘ash’ — let’s ring in the new year, Persian-style. The World from PRX. https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-03-21/fire-jumping-and-eating-ash-lets-ring-new-year-persian-style

Macedonian Boy. (2010, April 24). Macedonian Cross [Image]. wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macedonian_Cross#/media/File:Macedonian_cross.svg

Miles, C. A. (1912). Christmas in ritual and tradition: Part II. Pagan survivals: Chapter XVI. Epiphany to candlemas. Internet Sacred Text Archive Home. https://www.sacred-texts.com/time/crt/crt20.htm

Mirchevska, M. (2009). Holiday celebration of the population of gorna reka related to folk religion. ЕтноАнтропоЗум/EthnoAnthropoZoom, 6, 191-219. https://doi.org/10.37620/eaz0960191m

Muratov, D. (2020, March 1). Прочка – празник за проштавање и очистување од гревовите. CivilMedia. https://civilmedia.mk/prochka-praznik-za-proshtavane-i-ochistuvane-od-grevovite/

NA. (n.d.). Forgive and be forgiven – Today is prochka. WELCOME TO MACEDONIAN CUISINE ~ Macedonian Cuisine. https://www.macedoniancuisine.com/2017/02/forgive-and-be-forgiven-today-is-prochka.html

Papaskevopoulou (Παρασκευοπούλου), X. (2020, January 6). Έθιμα των Φώτων στη Μακεδονία. Parallaxi Magazine. https://parallaximag.gr/thessaloniki/reportaz/ethima-ton-foton-sti-makedonia

Tasnim NewsAgency. (2018, March 15). ČAHĀRŠANBA-SŪRĪ [Photograph]. commons.wikimedia.org. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%C4%8CAH%C4%80R%C5%A0ANBA-S%C5%AAR%C4%AA.jpg

Tylor, E. B. (n.d.). Rites and ceremonies. Primitive Culture, Vol 2 (7th ed.), 362-442. https://doi.org/10.1037/13482-007