Winter carnival festivities are spread through all of geographic Macedonia, having different names and referring to different aspects of the belief system. In some places they have already grown into festivals and in other places they still exist as customs, informal celebrations and social gatherings. They carry different names: babari, bamburci, eskari, golomari, jolomari, meckari, survari, vasilicari. The majority of them are associated with the pagan belief that the period immediately after the start of the new year is critical, because the new cycle is young and negative energies from the underground world are still wandering on earth ready to inflict evil. That is why we need regiments with scary masks to protect young life and to dislodge the evil.

These twelve days in the year from Christmas to Epiphany in folklore are known as unbaptized or Pagan days and believed to be the most dangerous days of the year. When these beliefs were adopted into the Christian annual cycle, they were associated with the life of Jesus. In these days Jesus had not yet been baptized and his Virgin Mother was still nursing. Christian demons took over the role of the evil force that was believed to be most potent against unbaptized people.

The traditional New Year Holiday in Zeleniche as in other villages in Macedonia followed the custom of chasing bad spirits away and was filled with three days of holiday cheer among family and friends and in the company of delicious home cooking, warm rakija and wine. According to the custom, at New Year’s people would change their clothes or wear them inside out, dress up as Eshkari ((Turkish = eski = old, ancient, worn – as they were known in the village) and celebrate for 3 days.

DAY ONE

On the first day, the men of the village would wait for the “Chulgagita” (bands) at the highway with their horses. The horses would be mounted without a saddle, only a “red” blanket, symbolic of ancient times. Once the bands (3 of them) arrived (4pm), they would start playing as they got off the bus with the mounted horses following behind them. They would circle the village and then stop at three different coffee shops and played past New Year’s.

Groups of friends would gather money to hire each band that would play at a specific coffee shop. They would provide room and board at their homes for the three days. Each gathering would be divided according to age groups, young, middle aged and older groups. Fires are lit again on New Year’s Eve, so that the new year can come faster.

The custom in Sklithro-Zelenić of purifying the village of bad spirits in time for the warm season. Archaeological findings dating back 2200 years suggest that Macedonians have been dancing and singing their way into Spring season for a very long time.

The people chase the evil spirits out of their town or village by building a big fire, which symbolizes the sun. The participants dress in bizarre animal skins and wear horns, dried gourds and cowbells. As the drum, the zurla and gajda are making a loud trance of sounds, the people dance the ORO (circle dance), skip around and yell out scary cries – much to the joy of bigger children and to the terror of the little ones.

DAY TWO

On New Year’s Day (second day), we celebrate the feast of St. Basil the Great, known among indigenous people as Vasilica. The celebration is symbolized with spinning zelnik (pie) with a hidden coin and other symbols. Whoever finds the money will be prosperous throughout the coming year. Other tokens in the basilopitta can be, a grapevine twig which stood for the ancestral vineyard, a straw and a dwarf-oak leaf for the cows and goats that feed on them, and an osier circlet for sheep. A cross of green was for the home, a purse for prosperity, and a ring for marriage.

Originally, many Macedonians used to cut the bread/zelnik with a coin on Christmas Eve. Church tradition adapted the custom and linked it to the life story of St. Basil.

Originally, the fortune cake/bread/zelnik was cut during Christmas day after the bon fires and the caroling of Koleda (Kalnada). The custom of celebrating Saint Basil on January first is practised by the Greek Orthodox Church. The city of Caesarea in Cappadocia where St. Basil came from celebrates his name day at Easter time as do the other sister churches of the Orthodox faith.

There is one event in the Eastern Roman Empire which tells that when an Emperor who wanted to destroy the city of Caesarea in Cappadocia was coming, Bishop Basil asked people to give some money (coins) to bribe the king in some way, so as to spare the city. Upon seeing the meger gifts, the Emperor proclaimed that he would destroy the city upon his return from battles with the Persians. But, the Emperor died and didn’t come back to the city so, Bishop Basil was confronted with the dilemma of how to return the coins back to the people. He ordered the city bakeries to knead bread in the city’s ovens and to put coins inside. Then the bread was divided among the citizens and everyone was returned exactly the same amount of coins as they gave. Because of this miracle, the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates St. Basil’s Day by placing a coin in bread.

According to its name, Basilopita is interpreted as meaning cake of Basil. Close consideration of this ritual, however, suggests that its association with the saint cannot be upheld, and that the popular interpretation of its name rests on a false etymology. The custom of celebrating Saint Basil on January first is practised by the Greek Orthodox Church. The city of Caesarea in Cappadocia where St. Basil came from celebrates his name day at Easter time. Even though the Eastern Orthodox faith has adapted this celebration, the people of the Balkan and especially Macedonians, this celebration is still inspired by nature, good health and bountiful harvests.

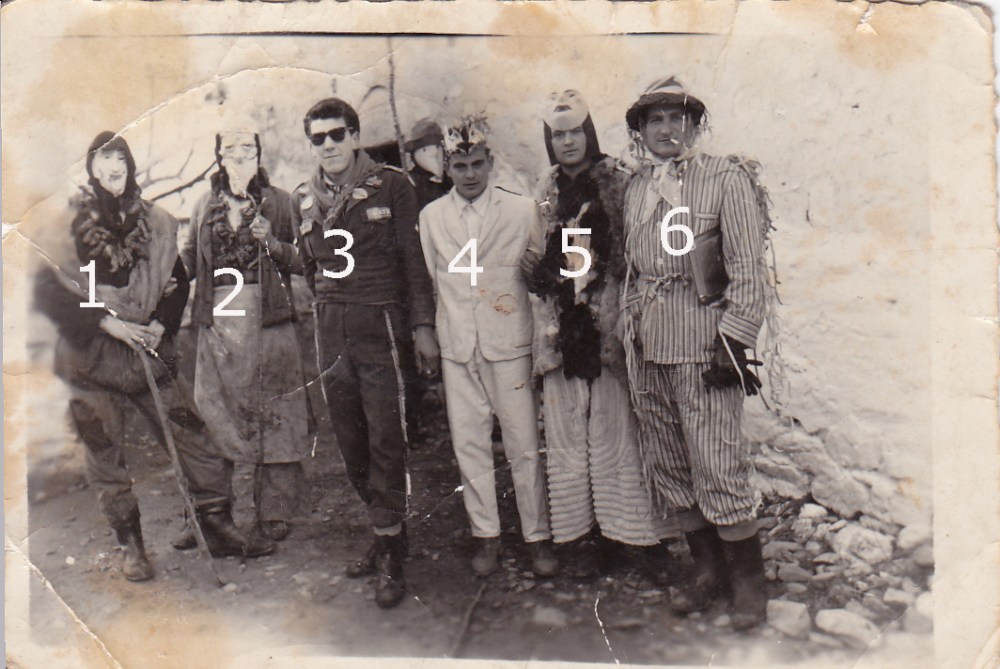

In the village of Zeleniche (Sklithro) after church and lunch, people would dress up as “Eshkari”( masquerade) and would go house to house. At each house that welcomed them, they would be treated with drinks and food. Then they would do the same right to the night. The “Eshkari” gatherings were composed of men, in which masked individuals accurately play their roles in the performances of traditional New Year rituals, games and songs, whose roots belong to the pre-Christian era, in they are dominated by desires for well-being, gender and fertility.

DAY THREE

On the third day of festivities plays with the wedding theme took place where only men played the main “actors”. It was some kind of a parody in which the main role was given to a bride (incarnation of fertility) and groom (phallic symbol), and their wedding guests from the village.

The central figure was the “bride” – a symbol of fertility, and the aim is to be abducted by the “bad guys”. Men were disguised with something that make them more frightening and put lima beans and red small dried peppers as teeth around their necks.

The men’s team consisted of about 15 people, wearing a linen shirt, a sleeveless vest and black woven knick-knacks, the fleece as well as large cowbells around their waist and thick woods – as crutches. Each member is also charged with a duty … vanguard, rearguard … side guarding of the bride … because the “bad guys” and, of course, the hunchback lurk.

They have to give her intact and untouched to the groom…who differs from the young men…in the crutches…which is a part of a sword-like plow…it also has a tassel …and small bells… The grandfather, the old lady (babo), the priest with the censer, the doctor with his medics and the shabby trickster of the bride (the hunchback) are certainly present at the event.

The bride is a man who wears a local bridal dress – every year he wears clothes of an unmarried woman in the village…in order to be pregnant – as well as horse bells. The team goes out and in the yards of the houses and the housewives must give the company Raki[a] (tsipouro), pork, sausages, onion, bread and wine. Under the sounds of the bagpipes, the daul and the flute … the heyday … is the lamming of the “suitors” of the bride and the hunchback.

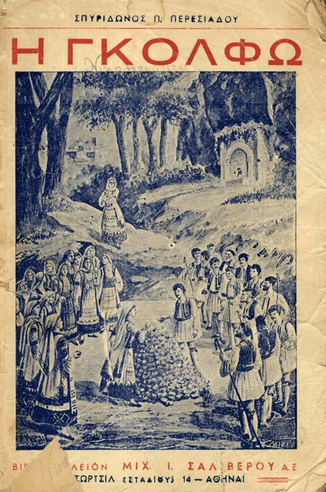

Through time, these rituals adapted to the changing of the political climate and the evolving economic and social conditions of the region. One addition to the wedding ritual was the adaptation of the lead characters, that being the bride and groom. Popular culture even reached Zeleniche with the inclusion of the 1915 Greek silent film Golfo. It is the first Greek feature film based on a popular Greek agrarian play written by Spyridon Peresiadis that was released on 22 January 1915.

Tasos a young shepherd in love with Golfo intends to marry her but, the rich shepherdess Stavroula with the help of her father manages to lure him with the promise of a dowry. Eventually Tasos realises his mistake and returns to Golfo, but she has poisoned herself. Driven by guilt, Tasos commits suicide.

The villagers in Zeleniche would act out this Shakespearean Romeo and Juliet play with theatrics and songs to the excitement of the villagers. The play would not end in sorrow, it would keep its customary ritual of getting rid of the bad spirits of the old year and welcome the cleansed new year as Tasos would eventually go back to his true love Golfo.

The real cultural roots of the festivities go back to the Pagan times, their beliefs and rituals. They are associated with the severity of the deep winter, the end of the annual cycle and the beginning of the new year. Our ancestors knew that the human health is the weakest in the cold and short winter days, and seasonal rituals were also meant to promote health. After centuries of existence, these customs survived the transfer from Paganism to monotheistic religions, and they still bear witness to how one belief system has replaced another leaving many loosely connected traces of the big collision.

After the Balkan Wars , WWI, and the Turko-Greek War of 1919-1922, each area of Macedonia that had been incorporated into the states of Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia, started to see influences imposed onto the customs of the indigenous Macedonian people. These customs continued to be passed on to younger generations but, in Greece, theologians and teachers urged students not to dress for the carnival, because the custom was pagan. Eventually religious authorities would ban them from being performed but, the indigenous people of the Florina and Kastoria regions would continue their festivities by preserving their customs.

Sources:

Abbott, G. F. (2011). Macedonian folklore. Cambridge University Press.

Al Bawaba. (2020, January 14). Paganism, humor, tradition: Old Vevcani Carnival celebrated in Macedonia. https://www.albawaba.com/slideshow/paganism-humor-tradition-old-vevcani-carnival-celebrated-macedonia-1332750

DMWC. (2017, February 2). On white snow under Black masks – Macedonia welcome center. Macedonia Welcome Center – Non-governmental non-profit organisation promoting Macedonian culture including cultural diplomacy in Macedonia and abroad. https://www.dmwc.org.mk/2017/02/02/on-white-snow-under-black-masks/

Facegreek. (2019, November 29). Christmas customs, Macedonia. https://www.facegreek.com/en/tradition/christmas-customs-macedonia

Fortune. (2005, November 6). Народна лирика – Peoples Ritual Songs. Кајгана форум. https://forum.kajgana.com/threads/%D0%9D%D0%B0%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%BD%D0%B0-%D0%BB%D0%B8%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0.1835/

Global Storybook. (2020, January 6). How Macedonians celebrate Christmas & the new year. https://globalstorybook.org/macedonians-celebrate-christmas-new-year/

IMDB. (1915). Golfo [Image]. http://www.imdb.com. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0123871/mediaviewer/rm710129153/?context=default

IMDB. (1915). Golfo [Image]. http://www.imdb.com. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0123871/mediaviewer/rm559134209/

Kalopedi N. (2005). Florina Macedonian Culture. Ελλάδα | Golden-Greece.gr. https://golden-greece.gr/mainland/makedonia/florina/culture

Macedonia Times. (2020, December 14). The Macedonian old new year – The time when we chase bad spirits away | Macedonia times. https://macedoniatimes.news/vevchani-carnival-old-new-year/

My Florina. (n.d.). ΗΘΗ ΚΑΙ ΕΘΙΜΑ – Carols and Fire. my Florina. https://inflorin.weebly.com/etathetaeta-kappaalphaiota-epsilonthetaiotamualpha.html