In the first century C.E. when Macedonia was a province under Roman occupation, the people accepted the teachings of Apostle Paul. Paul took this most important step of carrying over the doctrine of the Gospel from Troas to Macedonia in AD 51-54, and from there spreading it further in the countries across the rest of Europe. He made three missionary voyages in Macedonia. His voyages in Philippi, Ber (Lat. Beroia), and Thessalonika. Archaeological evidence also shows that besides these three cities in the first century AD in Macedonia many other early Christian communities were formed – in Amfipolion (Lat. Amphipolis), Bargala, Iraklea Linkesta (Lat. Heraclea Lynkestis, today Bitola), Lihnid (Lat. Lychnidos; today Ohrid), Skopje (Lat. Scopis), Stob(i), Tiveriopole (Lat. Tiberiopolis), etc..

Macedonia and Macedonian’s are distinguished as the very first people and nation on the European continent to have invoked and accepted the Christian religion at the very dawn of this era. Lidia, a young Macedonian woman from Philippi, was the first-ever baptized Christian on European soil. In the Macedonian Jerusalem, Ohrid, was founded the first ever known Christian church (St. Erasmo) on European soil in the 3rd century AD, and is the ultimate Holy See of the old Patriarchate/Archiepiscopacy of Ohrid. There is also the honorable plateau of the first known university in Europe – St. Clement’s University on Plaošnik.

In November of 284 A.D., Diocletian, split the Roman Empire in two. He kept the eastern part and gave the western half to his colleague, Maximian. In AD 295, the reforms of Diocletian (284-305) had seen Macedonia assigned under Diocese Moesia, one of the twelve newly established Dioceses of the Roman empire. The Diocese Moesia was then divided in two – Diocese Dacia and Diocese Macedonia. And the Provinces of Macedonia, Thessalia and Epirus Nova were reassigned under the Diocese Macedonia. Then emperor Valentian II (364-375) created the province of Macedonia Salutaris that comprised Macedonia and Dacia.

Oppression towards Christians lasted until 313 C.E. when Constantine I recognized and permitted the practicing of Christianity as one of the religions in the Roman empire. Later Constantine I the founder of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire moved the capital of the Roman Empire to the city of Byzantium in 330 CE, and renamed it Constantinople.

Holy Synods

After the legalization of Christianity by Constantine I the Great, within the Diocese Macedonia many Macedonian cities had risen into Episcopal Sees, testimonies in the records of participants of the first holy synods of all churches: the metropolitan episcope Dacus from the Skopje episcopacy (Lat. Episcopae Scopis), and Budimir and Evagriy of Stobi episcopacy are noted in the records of the very First Ecumenical Holy Synod of all churches in Nicaea (325 C.E.). Other Holy Synods include: the city of Tyre in 335 C.E.; Holy Synod in Serdica in 343 C.E.; Second Universal Holy Synod in Constantinople 381 C.E.; on the Ephesus Holy Synod in 449 C.E.; the 4th Ecumenical Holy Synod in 451 in Chalcedon. Macedonians were represented in each of these Holy Synods.

Romans not Byzantines

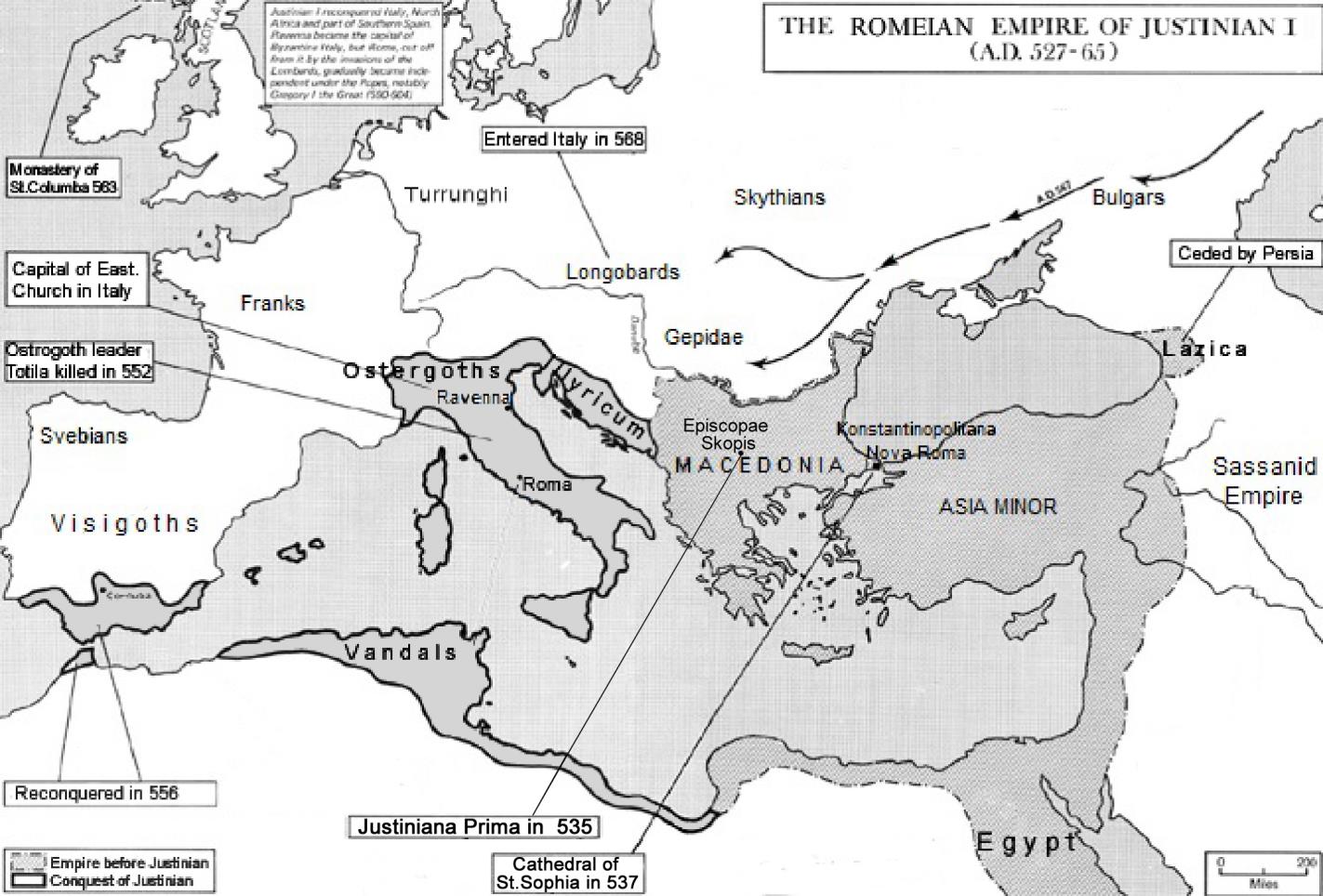

While the Western Roman Empire fell in 476 AD, the Eatern Roman Empire in the East lasted another 1,000 years. Its people never called themselves “Byzantines”; they considered themselves Rhomaioi, or Romans. While the empire was extremely cosmopolitan as the Roman identity bound Byzantines together, ethnic identities and divisions still existed. Early Byzantium was mostly ruled by emperors from the Balkans.

Latin continued to be used as the official language but in time it was replaced by Koine Greek as that language was already widely spoken among the Eastern Mediterranean nations as the main trade language. Yet the Emperors, the Church clergy, the army, and the artists, although they spoke Latin and Greek, where not exclusively of Greek ethnicity. The Empire was made up of many nationalities – Macedonians, Thracians, Illyrians, Bythinians, Carians, Phrygians, Armenians, Lydians, Galatians, Paphlagonians, Lycians, Syrians, Cilicians, Misians, Cappadocians, etc. The Greeks composed only a small portion of this multi-ethnic Empire and evidence shows that they did not posses much of the power either.

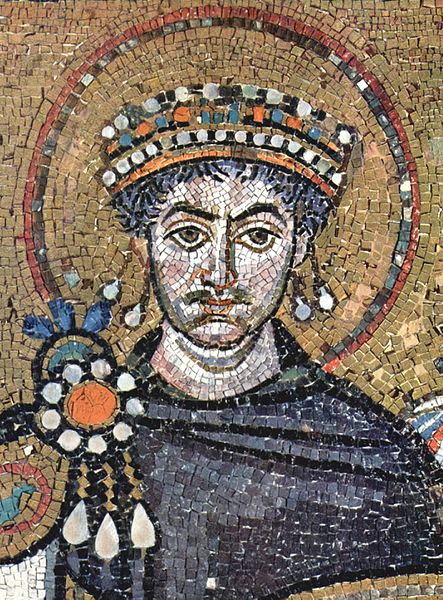

Early Byzantium was mostly ruled by emperors from the Balkans, with most of Macedonian origin. Some of the most prominent include Constantine the Great, who is identified as a Macedonian in a book entitled ‘De Magistratibus Ioannes Lydus’ which reports that Constantine the Great wrote, in his native tongue. The Lydian wrote his book between years 551 and 564 A.D., when Latin in Constantinople was in full retreat. Justinian himself is said to have spoken broken Latin, and Greek like a barbarian. This was two centuries after the death of Constantine. Clearly, throughout this period, there was in Constantinople people who could read Latin and/or Greek, and also people who could read Constantine’s Discourses, written in his “domestic” language.

The discovery of Justinian’s Biography (Justiniani Vita in 1883) shows that Slavonic tribes existed in Macedonia well before the 5th century, which predates the “Slavic Myth”and supports the Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm.

In 535 C.E. the Macedonian Apostolic Church finally received the recognition of its inhered dignities and God-given title, and was officially equaled by its apostolic right on the same level with the other apostolic and non-apostolic churches and holy sees in Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma, Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and Cyprus. Emperor Justinian I the Great then on 14 April 535 decreed the elevated status of Episcopal city of Skopje (Lat. Scopis) into independent Autocephalous Apostolic Archiepiscopacy and Holy See of the Macedonian Church in the Diocese Macedonia, with his very own imperial title of “Justiniana Prima”.

This Justinian’ 6th century imperial decree, beside despoiling the larger part of Macedonian peninsula from Rome’s sphere of (ecclesiastic) influence, generated a profound rupture and millennial animosity of the Roman Holy See toward everything Macedonian and Orthodox. Rome practically lost forever the previously conquered Macedonian territories. On top of that, this unprecedented destitution was executed by the hand of an emperor who himself was Macedonian by origin. This furthered the split between the Western and Eastern Roman Empire.

Thus, the Justiniana Prima was inaugurated “in perpetuum” as the third in rank official Autocephalous Apostolic Church. Its elevated status and privileges where definitely confirmed on the Fifth Ecumenical Holy Synod of the Church, where in 553 C.E. the renewal of Justiniana Prima was institutionally proclaimed and affirmed by the highest church instances. The (territorial) loss for Roman papacy was final and irrevocable – Macedonian peninsula and in particular Macedonia after 7 centuries of Roman occupation returned absolutely free from any kind of Roman domination.

Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm

The so called ‘late arrival’ of the Slavs in Europe can now be replaced by the scenario of Slavic continuity from the Paleolithic period, and the demographic growth and geographic expansion of the Slavs can be explained, much more realistically, by the extraordinary success, continuity and stability of the Neolithic cultures of South-Eastern Europe.

The Paleolithic Continuity Theory since 2010 relabelled as a “paradigm“, as in Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm or PCP), is a hypothesis suggesting that the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE) can be traced back to the Upper Paleolithic, several millennia earlier.

The old version of the traditional theory assumed, as is known, the ‘arrival’ of the Slavs in historical times, following their alleged “great migration” in the 5th and 6th centuries. This thesis is now maintained only by a minority. The arrival of the Slavs is now placed earlier – in the Bronze or in the Iron Age.

Ohrid Archiepiscopacy

Ohrid Archiepiscopacy (Justiniana Prima) was the next great step in the history of Macedonian Apostolic Church. After the fall of the emperor Maurice and under the pressure of the Avar, Bulgar, and other barbaric invasions from the northeast, in the year 602 C.E. retreated from Skopje to Ohrid. The Ohrid Archiepiscopacy fully inherited the jurisdiction over the same eparchies of Justiniana Prima. The highest presiding body of the Ohrid Archiepiscopacy was the Episcopal Holy Synod in Ohrid, constituted by episcopes from all eparchies, and was headed by the supreme patriarch, the Ohrid Archbishop.

The church organization from the (old) Justiniana Prima in northern parts of the Macedonian Peninsula declined after 614 C.E.. But even if heavily diminished in eparchies and cornered in Ohrid, the Macedonian Apostolic Church never ceased to be the supreme center and only reliable influential Christian institution in Macedonia and the wider region of Macedonian Peninsula. The forced restoration of Eastern Roman power in Macedonia during the reign of empress Irine subjugated the Macedonians in 783 C.E..

SS. Cyril and Methodius

In an attempt to subjugate the rebellious Macedonians, Constantinople began to colonize the region. The aim was to Romanize the Macedonians. Despite all efforts of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to maintain its dominant ecclesiastic and ruling position in the Macedonian Peninsula, due to linguistic affinities it failed. The imposed administrative Roman Latin and Romeian Septuagint version of Koine were inevitably replaced by the vernacular Macedonic liturgical language and the reformed Glagolitic Script that was used by Ohrid Archiepiscopate as of the 9th century – the Cyrillic. This modified Glagolic script, was adjusted for wider popular acceptance into a simpler version by SS. Cyril and Methodius, and later was renamed into “Cyrillic” by their disciples Naum and Kliment Ohridski, in honor of its inventor and compiler.

Seeing the relentless popularity of Macedonian Apostolic Church form of rite, the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma in the 9th century changed radically its policy toward the Macedonic liturgy and script. Acknowledging that they could not eradicate it, nor ignore the fact of its capillary-popular diffusion across the whole Macedonian Peninsula and central Europe, the Roman emperors then tried to use it as a tool in their avail, by recognizing it and helping its propagation. Nonetheless, in that time the Roman political power reached its apogee under the leadership of the Macedonian Dynasty (867-1056). As former territories were incorporated in their empire, through the Macedonic Apostolic Church disciples and their vastly popular preaching and liturgy, they re-approached the old era Macedonic cosmopolitan element of multicultural policy.

The most responsible for this great Macedonic revival were the two erudite Macedonian priests and saints, Cyril and Methodius. They were born in Thessalonika (Solun) in the family of a well-to-do Roman drouggar (lat. Drouggarios – a military and administrative official in the Roman empire) by the name of Lav. Born in 826 C.E., Cyril was the youngest of the seven children in the family. Methodius was about ten years older. The countryside around Thessalonoka was predominantly Macedonic, and the brothers grew up with a native knowledge of the local Macedonian dialect. After having the best education of their time they became the finest ecclesiastic and diplomatic agents of the emperor and the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma.

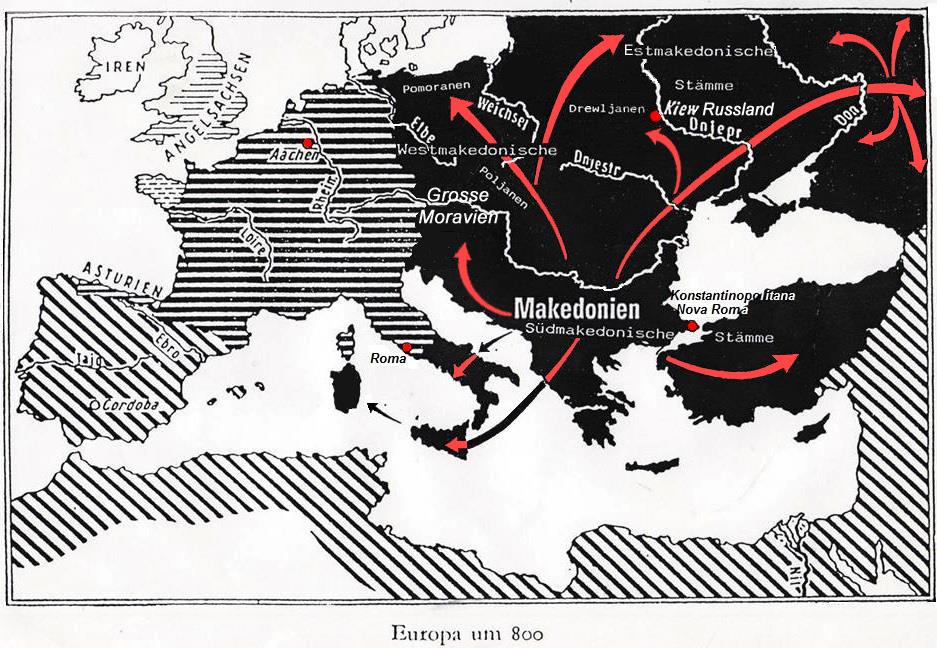

First the Principality of Raška (i.e. today Servia/Serbia) due to geographical, ethnical and ecclesiastic vicinity officially adopted the Old Church Macedonic rite and Glagolic/Cyrillic script from Macedonia already in 862. In 863 the prince Rastislau of Great Moravia followed suit and requested from Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma to send Macedonic Christian missionaries, in order to introduce the Macedonian rite and script in his kingdom, in a language that his people could understand.

Emperor Michael was fully aware of the power of Old Church Macedonic rite, and its profound acceptance as a medium among the Macedonic population across the Macedonian peninsula. No other tongue, neither the Roman administrative Latin, nor any other language had the Macedonian immaculate and sincere intimacy to the Word of God, emperor Michael correctly saw in it the opportunity of further enlarging his authority and empire’s influence abroad.

SS. Cyril and Methodius first mission amongst the Moravians took place during that Macedonian Renaissance period, as the Eastern Roman empire entangled into great political turmoil and opened up for the first time to the world. In 870 C.E. the Glagolithic/Cyrillic script became the fourth official holy alphabet (after Hebrew, Septuagint Koine and Latin) with which the word of god was to be preached.

All these events occurred in the course of a single decade, the sixties of the ninth century. This period is also significant as the time in which the reinforced and newly institutionalized Macedonic culture had strong influence among the Macedonians and other Macedonic peoples across the Macedonian Peninsula. It was indeed a great decade in the history of Macedonia and the Roman empire. Thus, the Macedonian Apostolic Church and its Holy See in Ohrid never ceased to be the main epicenter of the Macedonic culture and Christianity, even though the Ohrid Archiepiscopacy was still within the political sphere of interests of the Eastern Roman empire.

Then (in the 10th century) the Glagolic/Cyrillic liturgy in the Old Church Macedonic language finally reached Kievan Russia, where it became the official ecclesiastic language and script, and from there spread across other areas in Eastern Europe, Asia and Africa (Coptic). Namely, after the Russian attack on Konstantinopolitana Nova Roma in AD 860 intensive collaboration and contacts with Macedonia and Macedonian Apostolic Church began in the newly formed Russian state. Kiev, then in open war with Constantinople, looked for Christianity elsewhere – in Macedonia. In the following (10th) century, in order to assist its ally against Eastern Roman empire, Tsar Samoil sent from Macedonia to Kievan Russia episcopes, priests and deacons, and loads of holy books, with which were laid the foundations of the Russian Orthodox Church hierarchy, liturgy and literacy. And after the official conversion of the Russians to Christianity in 988 C.E., volumes of Christian Macedonic education, culture and traditions carried by the Macedonian clergy, continued to flow from Macedonia to Russia.

As Paul R. Magosci explains: “One thing is certain: the written language of Kievan Rus’ was not based on any of the spoken languages or dialects of the inhabitants. In other words, it had no basis in any of the East Slavic dialects, nor did it stem from some supposed older form of Ukrainian, Belorussian or Russian. Rather, it was a literary language, known as “Old Slavonic” (read “Old Macedonic!”), originally based on the dialects of Macedonia, an imported linguistic medium based on Old Macedonian.”

At that time the Russian church’s position was under the jurisdiction of the Archdiocese of Macedonia and the then Ohrid Patriarchate (969-1018 C.E.) and later Archiepiscopacy until 1037. Macedonian influence was the most fundamental in the first years of Christianity in Russia.

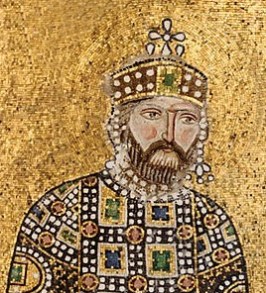

Macedonian Dynasty

It is known that the Eastern Roman Empire reached its zenith while it was ruled by the Macedonians emperors of the late 9th, 10th, and early 11th centuries, when it gained control over the Adriatic Sea, Southern Italy, and all of the territory of the Tsar Samoil of the independent western Macedonian region of the empire during the Macedonian Dynasty. Basil I, called the Macedonian, was a Byzantine Emperor who reigned from 867 to 886. Born a simple peasant in the theme of Macedonia, he rose in the Imperial court. The Macedonian Dynasty introduced a new era of education and learning, as ancient texts were more readily preserved and copied art was once again allowed within the empire.

Macedonian Renaissance is a label used to describe the period of the Macedonian Dynasty of the Byzantine Empire (867–1056). The reign of Basil II (976-1025), the longest of any Byzantine emperor has been considered a “golden age.” While Basil II was busy fighting in the East, in the west, the first independent Macedonian state to arise after the Roman conquest was established by Tsar Samoil in 976 C.E. lasting until 1018, following the defeat at the hands of the Basil II and the Byzantines.

As recorded in Byzantine chronicles, Basil II, the new Byzantine emperor, invaded Western Macedonia almost “every year” and gradually succeeded in capturing and destroying a number of strongholds. The fall of Durres and of the fortified towns on the other side of the Maritsa River and the submission of Greater and Lesser Preslav, Pliska, Veria, Servia, Voden, Vidin, Edirne and Skopje considerably eroded Samuil’s power. The decisive battle between Samoil and Basil II took place at the foot of Mt. Belasitsa on July 29, 1014. In essence it was a civil war between a Macedonian Emperor of the the Eastern Roman Empire and an independent Macedonian noble (king) breaking away from the empire.

Basil’s greatest achievement was the annexation of the first independent Macedonian state after the early Roman conquests and four wars over Macedonia. This, we have been told, was achieved through a long and bloody war of attrition which won Basil the grisly epithet Voulgartoktonos, “the Bulgar-slayer.” In this new study Paul Stephenson argues that neither of these beliefs is true. Instead, Basil fought far more sporadically in the Balkans and, like his predecessors, considered this area less prestigious than the East. Moreover, his reputation as “Bulgar-slayer” emerged only a century and a half later.

Samoil’s empire was not Bulgarian, but rather a “Macedonian kingdom, ” as the great Byzantologist Ostrogorsky refers to it, “was essentially different from the former kingdom of the Bulgars. In composition and character, it represented a new and distinctive phenomenon. The balance had shifted toward the west and south, and Macedonia, a peripheral region in the old Bulgarian kingdom, was its real center.’’

Thereafter the “Bulgar-slayer” was periodically to play a galvanizing role for the Byzantines. Fading from view during the period of Ottoman rule, Basil returned to center stage as the Greeks struggled to establish a modern nation state. As Byzantium was embraced as the Greek past by scholars and politicians, the “Bulgar-slayer” became an icon in the struggle for Macedonia (1904-8) and the Balkan Wars (1912-13).

Although Byzantine emperors were ethnically diverse, there was a pattern in which ethnicity dominated the throne. The early Byzantine rulers were mostly Macedonians from the Balkans, ethnically Armenian emperors dominated the middle Byzantine period, and the final era of Byzantine history was presided over by ethnically Greek emperors. In the latter period, the Balkans and Macedonia became independent of Byzantine rule. As the Eastern Roman Empire was busy fighting its enemies in the east, the western provinces were creating their own independent kingdoms.

Thus, the Eordai region where Sebalci (or Cebalci) was located, was at the centre of a continuous Macedonic identity that evolved throughout the Eastern Roman empire.

Sources:

- Alinei, M. (2000). The Paleolithic Continuity Paradigm – Introduction. Retrieved from http://www.continuitas.org/intro.html

- Alinei, Mario (2003b), Interdisciplinary and linguistic evidence for Palaeolithic continuity of Indo-European, Uralic and Altaic populations in Eurasia, “Quaderni di Semantica” 24, pp. 187-216.

- Angelovska, M. (n.d.). The Bogomilism: historcal and cultural context. Retrieved from http://www.academia.edu/9023491/The_Bogomilism_historcal_and_cultural_context

- Basil I | Byzantine emperor. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Basil-I-Byzantine-emperor

- Chao, K.Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/

commons/7/7b/MMA_bust_02.jpg

- Chulev, B.Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/33684908/Macedonian_Apostolic_Church_-_Ohrid_Archiepiscopacy.pdf

- DIRECTMEDIA.Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia

.org/wikipedia/commons/8/89/Meister_von_San_Vitale_in_Ravenna.jpg

- Magocsi, P. R. (2010). A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Obolensky, D.Retrieved from http://media.hoover.org/sites/default/files/documents/Macedonia_and_the_Macedonians_Andrew_Rossos_19.pdf

- Roke-commonswiki. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/Byzantine_Empire_animated.gif

- Sotiroff, G. (1974). The assassination of Justinian’s personality.

- Vagen, A. Retreaved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/22/Hagia_Sophia_Mars_2013.jpg

- Winters, R. (2015, June 13). The Forgotten Renaissance: The Successes of the Macedonian Dynasty. Retrieved from https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-important-events/forgotten-renaissance-successes-macedonian-dynasty-003227