The Origins of the Balkan Wars

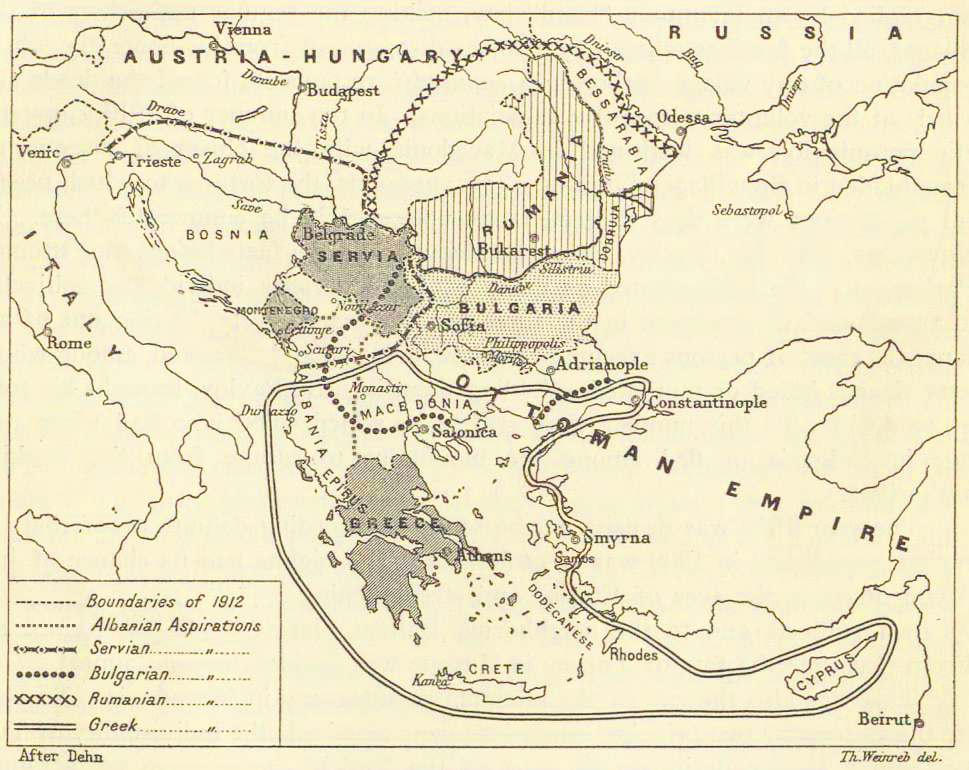

The Congress of Berlin (June 3, 1878) took place about three months after the signing of the Treaty of San Stefano. Its goal was to reorganize the Balkans after a long period of instability which resulted in the signing of the single most important document in the nineteenth century in tracing the frontiers of the Balkan countries. The Berlin Treaty following the war created a status quo which lasted almost 35 years. This treaty left many issues unresolved in the Balkans and especially for the Macedonian Christians.

At the core of the Balkan states decision to start a war was the possibility that the new regime in Istanbul, emboldened by the successes of the recent revolution, could demand a new set of arrangements regarding the status quo in Macedonia, maybe the application of Article 23 of the Berlin Treaty in Macedonia. Article 23 of the Treaty stated that statutory changes would be introduced in the Macedonian vilayets, similar to the status of the island of Crete. These reforms were to provide a certain level of political autonomy granted to Macedonians, but the Porte (Turkish government) prevented this and the Great Powers were reluctant to pressure the Turks to implement the reforms promised in the constitution.

Germany, France, England, Russian, Italy and Austria- Hungary used the Treaty of Berlin of 1878 to give the Macedonian vilayets back to the Turks while gaining concessions for the benefit of their own states. In the 35 years between 1878 Berlin Treaty and the first Balkan War of 1912, all the Great Powers made gains in the Balkans. Instead of allowing the Macedonian vilayets to be freed from the Ottoman yolk, they were more interested in preserving the integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

Macedonia held various strategic advantages: “commanding the communication route down the valleys of the Vardar and Morava and offering both Bulgaria and Serbia a vital outlet to the sea. It also had considerable agricultural wealth and whoever managed to take control of this territory would hold significant power and quite possibly be able to dominate the region.

For the Turks, on top of being a great source of revenue, Macedonia housed more than a million Muslims and served as a buffer against the threat Greece posed to Ottoman imperial territory. By 1908 the Austrian annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina, the joining of Crete with mainland Greece and most of all the independence of Bulgaria created new threats for the Ottoman Empire.

Macedonians

Macedonian Christians, whose adherence was disputed between the Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian churches, could therefore assume the nationality corresponding to the respective religious communities. The independent Macedonian movement was attacked and prevented from formalizing its authority over Macedonia and being recognized by the Great Powers. In fact, it was the Great Powers which prevented Macedonia from gaining its freedom because of the Treaty of Berlin. Under the threat of violence/death, Macedonians were cornered to transfer to another religious community, by doing so, they would also be forced to change their nationality. Macedonian Muslims, however, were generally considered to be Turks.

The principal contentious subject in Macedonia before the Balkan Wars was the national identity of the Christian Macedonian. The statistics presented by Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia did not recognize a Macedonian nationality, as it would have implied that most of the inhabitants of Macedonia had no ethnic relationship with them and that their influence on the Macedonian element had no legitimacy. Moreover, statisticians in each state used to manipulate the figures to make them more politically advantageous. The Ottomans also increased the number of “Turks” within Macedonia in their figures to justify their ongoing rule.

The Macedonians were generally regarded as Bulgarians in the foreign countries. Indeed, when the Bulgarian Exarchate arrived in Macedonia in 1872, many Macedonians left the Patriarchate church to join the Exarchist one. However, Macedonians were more attracted by the linguistic similarity of the Bulgarian church than by a nationalist sentiment. They never wavered from their desire for an independent and free Macedonia for Macedonians.

The Greek minority in Macedonia occupied a very limited portion of the territory. They were scattered alongside Wallachians and Macedonians in the southerly parts of the Monastir (Bitola) vilayet. According to most statisticians, Greeks represented a small fraction of the population at the time. The confusion between Vlachs and Greeks and Patriarch Macedonians led to a considerable overestimation of the number of Greeks living in Macedonia. Greek propaganda aimed at making the Macedonians and Wallachians join the Patriarchal Church of Constantinople was designed to legitimize Greek territorial claims in Macedonia.

The statistics issued by the Greek government on the number of Greeks in Macedonia were always exaggerated. The high conversion rate from the Greek Patriarchate to the Bulgarian Exarchate from 1872 to 1912 was indicative that most Macedonian Christians did not consider themselves to be Greeks. Those who converted back to the Patriarchy did so out of coercion and threats of violence and death as in the case of the village of Zelenich and the “Bloody Wedding.”

The territorial claims of the Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian states found their legitimacy in the number of adherents to the churches controlled by these states in the regions they aspired to obtain. Propaganda campaigns, presenting population figures, were carried out to promote this legitimacy at the international level, with each state trying to minimize the number of adherents of its rivals by claiming Macedonians as their own.

First Balkan War

Claiming to liberate the Ottoman Christians of Europe from increasing maltreatment, in October 1912 the armies of the Balkan Alliance invaded the Ottoman Empire’s European territories, Macedonia included. Their joint invasion launched what became known as the First Balkan War. By the beginning of December 1912, the Balkan states’ armies pushed Ottoman forces out of almost all the Empire’s vast remaining European territory.

The emergence of independent states in the Balkans, eager to enhance their territories, felt threatened by the political changes in the empire that culminated in the Young Turk revolution in 1908. The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908) was a Constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. With a Constitutionalist revolt in the Macedonian provinces instigated by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), Abdul Hamid (Sultan) capitulated and announced the restoration of the Constitution, recalled the parliament, and called for elections.

The indigenous Christian revolutionaries put down their weapons and joined the Young Turks by being elected to the Ottoman parliament. Change was in the wind and the world was relieved with the possible end to hostilities in European Ottoman territories. Macedonians, Vlachs, Albanians, Bulgarians, Serbs and Greeks were elected to the Ottoman parliament as their ethnic communities gained representation in this new Ottoman government that initially showed signs of becoming more secular and tolerant.

But this was not in the works for the competing rivalries between the Great Powers, particularly Austria-Hungary and Russia who were competing for influence over the region. France, Germany, Italy, and Britain each had their own interests for not supporting the Young Turk revolution. They all had supported the competing Balkan countries by arming them to the teeth. This became the start of an arms industry that would have a great influence in the Balkans and the whole world in the years to come.

Even though the indigenous Christians of the Macedonian vilayets and Thrace ceased their revolutionary activities in 1908, the competing nations of Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria, continued to send their mercenary terrorists into the Balkans, preventing any real change from taking place. This forced the Young Turk revolutionaries of CUP (Committee of Union and Progress) to become more radical and began terrorizing Christians. As a result, the indigenous Christians who had been promised change, took up arms and moved to the mountains once again.

The failed attempt of the Young Turk Revolt to establish a parliamentary regime and quell the turmoil witnessed an increase rather than a decrease in the inter-ethnic tensions within the empire. This increase was due to the constant incursions of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian nationalist militias that terrorized Macedonians to first join their churches and schools and then their nationality. The Greek Anti-Macedonian Struggle in combination with the Serbian and Bulgarian ambitions of annexing the Macedonian provinces, became one the core problems leading to the outbreak of the Balkan Wars.

The area where such conflicted interests clashed the most proved to be the Ottoman territories of Macedonia”. Bulgarian independence brought more turmoil to the Macedonian provinces as the activities of local insurgents had again brought chaos. Even though Greek activities only terrorized Macedonians, this forced Bulgarians and Serbians to increase their activities of assimilation and as a result, the new Turkish regime (1909) began implementing stricter policies under “constitutional reforms,” that made the Christian communities lose many of the privileges they had previously enjoyed.

In 1910, Serbia, Greece, Bulgaria, and Montenegro, officially created an alliance the counter the aggressive policies of the Young Turks and expansionist Austro-Hungarian ambitions. The cordial relations between Serbia and Greece made it easy to formalize their cooperative relationship. The most difficult was the Serbian and Bulgarian with their own unique claims on Macedonia. Despite their differences by the summer of 1912, all four nations signed a purely defensive alliance and did not contain any aggressive designs, despite being inherently anti-Ottoman in nature.

By 1912, the situation in the Balkans was deteriorating as tension was increasing among the Great Powers, but also the local Balkan states, especially the Serbs. Austrian involvement in Bosnia-Herzegovina and their attempt to secure an autonomous Albania to halt expansionist efforts in Serbia and Montenegro created an uncertain climate in the Balkans. The Austrians were more concerned with keeping the status quo in Ottoman Europe as were the other Great Powers, especially the British and French. They went as far as omitting the word “Christians” from the original text of reforms for Macedonia.

It was evident that the Great Powers were more concerned with following the Articles of the Berlin Treaty of 1880 or amending the treaty to keep the Ottoman Europe in tack all the while preventing any large foreign intervention. If the Great Powers had excepted the terms of the San Stephano Treaty of 1878 between Turkey and Russia, where the Turks had lost all their territories in Europe, the Macedonian provinces, Thrace, and Bosnia-Herzegovina would have been free to determine their own fate over the 34 years between 1878 and 1912.

By September, the reluctance of the powers to take any further steps and the failure of the Ottomans to display any tangible progress on the implementation of reforms meant the diplomatic situation had reached a deadlock.Meanwhile, the situation further deteriorated as the Christian communities in Macedonia became restless as the Albanians received concessions and Christians received none.

THE WAR BREAKS OUT

On 8 October 1912, Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire, the other Balkan states soon followed, declaring war on 18 October with the League following suit. The battles that ensued were fought almost entirely on Macedonian soil, once again causing the Macedonians to suffer from someone else’s war.

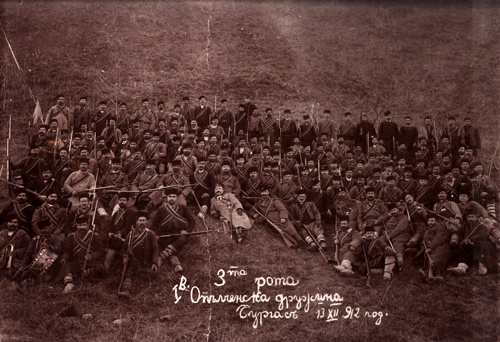

Macedonian Militia force of over 14,000 fought under the Bulgarian command in the East.

The Bulgarian army, numbering more than 350,000 men, advanced mainly to the South, to attack Adrianople and Salonika.

The Greeks, having mobilized nearly 110,000 men organized in four divisions, advanced northward to take Salonika.

Serbia and its 230,000 men divided into three armies, advanced towards Monastir. The Montenegro army numbered about 35 000 men and was advancing eastward to try and conquer Macedonian territory.

Macedonian Militias prepared the way and fought with Greek and Serbian military and paramilitary groups against the Ottomen.

The Ottoman Empire, weakened by military reforms initiated by the Young Turks, and by the Italian front in Libya still managed to gather a large number of troops on the battlefields. The Ottoman army fought on two fronts: the first in Thrace, where it faced attacks from Bulgaria and Greece, and the second in Macedonia, where it fought against the combined forces of Serbs, Greeks, and Montenegrins.

To everyone’s surprise however, the League won a crushing and unexpected victory in just six weeks. Five Ottoman divisions were surrounded and defeated in two battles in Bitola and Kumanovo. With the exception of Sandanki and a force of 400 Macedonians who fought back and liberated Melnik and Nevrokop, the League received no opposition from the Macedonians. In fact, the enthusiasm created by the “liberators” not only helped the League fight harder but also encouraged thousands of Macedonians to enlist in the League’s armies.

Zelenich Contingent

At the outbreak of the Balkan War in 1912, there were seven Zeleniche volunteers in the Macedonian-Edirne (Adrianopolitan) militia. The Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps was a volunteer corps of the Bulgarian Army during the Balkan Wars. It was formed on 23 September 1912 with 14,670 personnel (11,470 were from Macedonia, 1,215 – from Thrace, and 2,512 – from Bulgaria) and consisted of mainly Macedonians volunteers. Some of the none names from Zelenich included Lazar Dimitrov Bitsarov, Foti Nokolov Kirchev, Stefan Nikolov Kalfa and Petar Stoyanov.

Despite the vast majority of its membership’s ancestry in Macedonia rather than in Adrianopolitan Thrace, the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps was sent to operate with the bulk of the Bulgarian army in the Thracian campaign instead of in Macedonia. The corps’ deployment away from the Macedonian theater, along with the later revelation that Bulgaria and its ally Serbia in their pre-war negotiations had only paid lip service to the notion of Macedonian autonomy in favour of partition of the territory, eventually became the cause of bitterness among many of the corps’ members. They would begin to desert in large numbers the following spring. Macedonian emigrants in Serbia and Greece also volunteered to serve in the war efforts of their respective host countries.

“A Macedonian Militia force of over 14,000 fought under the Bulgarian command in the East. The ‘Volunteer regiment’, directed by IMRO veterans, consisted of a thousand Macedonians, Ottomans and Albanians. In the Serbian and Greek armies, Macedonian detachments such as the ‘National Guard’ and the ‘Holy Band’, were given the task of encircling the Ottomans to fight their retreat.” Even Chakalarov from Klissura, the protector of the Lerin and Kostur regions, joined the fight to help the League get rid of the Ottomans. The League’s victories and intense propaganda were so convincing that the entire Macedonian nation welcomed the “liberators” with open arms.

In view of the Macedonian contribution to the League’s success in evicting the Ottomans, on December 12th, 1912, Sandanski called for Macedonian autonomy. The League’s occupying armies however, refused to budge and initiated a violent assimilation program. The Macedonian fighters that fought side by side with the League’s armies found themselves policed by a joint League command ensuring that no resistance or independent action would arise.

By February 1913 the Bulgarian General Staff was struggling to combat demoralization among a large part of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps who wanted to return to their homes in Macedonia and apparently saw little connection between their fighting in Thrace on Bulgaria’s behalf and their personal aspirations for a liberated Macedonia. A large number deserted on the eve of the Second Balkan War, defying arrest by Bulgarian authorities for some time by travelling in armed groups.

The changing conditions inside Macedonia forced the IMRO leadership to seek refuge in foreign cities away from home. Some of the more prominent leaders moved to St. Petersburg and joined the Macedonian community living there. This small group of Macedonians consistently lobbied for Macedonian Statehood and in the war’s aftermath, acted as a government in exile. The most outspoken advocate of the Macedonian leaders was Dimitar Chupovski who published the “Macedonian Voice” and continuously protested to the Great Powers against Macedonia’s partition.

By November it was becoming apparent that Turkey was running out of options and on November 12th, 1912, called on the Great Powers to bring about an armistice. To deal with the situations, a peace conference was scheduled for December 16th, 1912, to take place in London.

It was well known that a Macedonian Nation with a Macedonian consciousness existed and demonstrated its desire for independence. These actions were well documented and familiar to the Great Powers, yet even after pleading their case, the Macedonians were NOT ALLOWED to attend the London Peace Conference of December 16th, 1912.

Numerous petitions were made by IMRO affiliates from St. Petersburg, all ignored. Also, Chupovski’s memo, to the British delegation, was not tabled. Here is what Chupovski (in part) had to say; “In the name of natural law, of history, of practical expediency, for the Macedonian people, we ask that Macedonia’s right to self-determination be admitted, and that Macedonia be constituted within its ethnic, geographical and cultural borders as a self-governing state with a government responsible to a national assembly.”

The Albanians on the other hand, had a country created for them even though they did not have a revolution or even demand for a country. In fact, they fought with the Ottoman against the Greeks and Serbians. The denial of an autonomous Macedonia state for a people who fought with the Balkan League against the Ottoman oppressors were now being oppressed by their liberators. On the 20 April 1913, all parties ceased fighting while negotiations regarding the re-partition of the conquered territory were conducted.

Zelenić Region of Western Macedonia – First Balkan War

The following are excerpts of British Consular letters in Monastir sent by Vice-Consul Greig to Sir G. Lowther Monastir:

October 29, 1912

- October 28: 1,500 Malissores, from Dibra, arrived here under the orders of Sefedin Bey Pustina, and 300 under the orders of Shaquir Bey of Dibra. Nine hundred and twenty Albanian volunteers, accompanied by Mersim Dema, Ejup Sabri, and Niazi Bey, without uniforms and armed with Martini-Henry rifles, left Monastir for Sorovich. (Niazi Bey has since gone to Neveska, south of Florina, where he will no doubt be exposed to less danger than in Kailar or Verroia, with the alleged intention of confronting the Greek gangs.)

- The morale of the officers and men seems completely shaken. Many have deserted and are on the run.

November 11:

- The III Division under Lieutenant General K. Damianos marched from Zelenich (Sklithro) to Klissura and stopped in the town of Zagorićani (Vassiliada).

- In the morning hours of November 12, the 1st Cavalry Regiment entered Kastoria and a little later the entire III Division.

November 16

- Greek troops advancing towards Monastir, were much weaker than expected and very inferior to the forces of Javid Pasha. They consisted of 10,000 to 12,000 men of the 5th division, with twelve field guns, and two cavalry squadrons commanded by an officer named Mathiopoulo. Those troops occupied Sorovich and, freely crossing the Kirli Derbend, took position at Ćerovo, forcing the Turks to abandon the railway line south of Florina.

- The 3rd Current, Djavid Pasha, who was then in Banitsa with the 16th and 18th Divisions, sent its right wing (the 17th division and the Monastir editorial division) to Sorovich, passing through Vrtolom, Leskovets and Negovani, while the 6th Nishanji Regiment occupied Gornichevo, on its left flank. He then himself advanced towards Ćerovo.

- The offensive, launched on the 3rd, seems to have resumed on two fronts on the 4th, when the Nishanji regiment from Gornichevo took over the hills to the east of the Greek positions. This maneuver sealed the outcome of the battle, as the Greeks mistook the Nishanjis for a greater force and evacuated Ćerovo by falling back towards Sorovich.

- Despite heavy losses, they withdrew in good order by taking the pass. However, on approaching Sorovich, they realized that the Turkish right wing threatened their retreat. Panicked, they ran away towards Kailar, abandoning all their artillery at the Nalbandkoj bridge. They would have been annihilated if Djavid Pasha had had a considerable body of cavalry. The chase has relaxed in Nalbandkoj and seems to have ceased altogether around Kailar.

- Djavid Pasha estimates that the Greeks lost between 1,500 and 2,000 men and claims that the Turks have only 60 casualties. He got hold of twelve cannons, a large number of rifles and a large amount of medical equipment. Seventeen Greek prisoners, including a non-commissioned officer, were brought here (Monastir).

- Djavid Pasha returned to Monastir on the 7th joined with the 16th and 18th divisions, leaving the 17th division in Kailar, and the one division of Monastir in Eksisou. The latter would now be between Banitsa and Ostrovo, and a Greek column of unknown strength would lie between Vladovo and Ostrovo.

- The Greeks occupy Vodena and use the railway between Gida (and possibly Salonika) and Vladovo. The Turks destroyed part of the line between Pateli and Ostrovo. From the 3rd current, we vaguely knew here that a force comprising a part or all of the 5th Army Corps, under the command of Kara Saïd Pasha, retreated towards Monastir via Vélès and Prilep, and that the 7th Army Corps, commanded by Fethi Pasha, approached via Kalkandélén and Kitchévo, and that both fell back before Serbian or Serbo-Bulgarian columns, whose strength was unknown.

- The return of Djavid Pasha and the 16th and 18th divisions to Monastir, after pursuing the Greeks, was due to the disastrous course of the campaign in the North. The pursuit of resistance would be mainly due to the effort led by Javid Pasha. To restore to some extent the morale of the troops opposed to the Serbs, the soldiers who remained in Kailar and Eksisou after the victorious campaign conducted against the Greeks were gradually incorporated into the battalions of Fethi and Kara Saïd Pasha and replaced by fugitives from Kitchévo and Prilep.

- The Greeks were busy racing to reach Saloniki before the Bulgarians, so their movement into the area was limited in numbers. The Turks were more concerned with the Serbs forces to the north and it is these forces that eventually defeated the divisions in Monastir.

Albanian volunteers:

- The authorities offered them old models of Mausers (with a nine-round magazine), which they refused. After claiming rifles from the most recent model, the stocks of which are completely exhausted, they have persuaded to accept Martini-Henrys. It is generally believed that these irregulars have the sole objective of obtaining guns, and that the majority of them will desert at the first opportunity

- The Turks attributed their defeat to their weaker artillery, to the numerical superiority of the enemy, the lack of ammunition for machine guns, and the panic caused by the flight of large numbers of Albanian

The following are excerpts following Greek military archives to the so-called liberation of Western Macedonia and the village of Zelenich:

- On the first day (October 6, 1912) of the war the Greek army crosses the border and fighting starts with the Turkish army. By October 11th the Greek army is able to reach Kozani and cross the Aliakmona river. The Greek leadership decides to put most of its forces focussed on reaching Saloniki before the Bulgarians. The 5th Division remains in Kozani and moves north to Kailari (Ptolemaida) and takes the city on October 15.

- At the same time, the former paramilitary groups that terrorized the indigenous Macedonians were now sent to secure major river crossings and mountain passes for the invading Greek army. The butchers of Zelenich, Zagorićani, Nevoljani and the rest of Western Macedonia (Karavitis, Makri and Kaoudis) were now using their terror tactics on Muslims and the Turkish forces that protected them during their “Anti-Macedonia Struggle.”

- By October 18th the Greek forces reached Sorović (Amyntaio) with little Turkish resistance. They then moved through the Kirli Derven pass (Kleidi Pass) without any disturbance and entered Banića (Vevi) on October 19th, to Zambirdeni (Tumba) and then Negovani (Flambouro). The goal was to liberate Lerin (Florina) first and then onto Monastir (Bitola). Up to that point, the Turks were constantly retreating, leaving the Greek army free.

- But now a section of Zeki Pasha’s Army commanded by Xavit Pasha, who was fighting against the Serbs, descended south and turned against the Greeks. A battle ensued in the village of Lofoi (October 21) and the Greek Army retreated to the pass at Kirli Derven (Kleidi Pass) and were successful at repulsing the first Turkish attack (October 23). That same night a small Turkish unit stationed in Neveska attacked the Greeks from the rear near the village of Rodonas and created panic. The Greek 5th Division in order to protect its retreat retaliates and sets fire to Exchiso/Varbeni (Xino Nero) and Sorović (Amyndaio) on their way back to Kozani through Kailari (Ptolemaida).

- In Kozani the army was reorganized and reinforced with reserves and volunteers and are turned to taking Saloniki (Thessaloniki). With the reorganization of the 5th Division the Greeks turned west to Voden (Edessa) and take it on October 30 and Arnissa (Nov. 4); Kailari (Nov. 5); Sorović (Nov. 6). The 4th and 5th Divisions then take the Kirli Derven Pass and march to take Keli (Nov. 6) and Lerin (Nov. 7).

- On November 8, the Greeks managed to reach Salonika and the Bulgarians entered the city the next day.

- On November 9th the Cavalry Regiment arrives in Zelevo (Antartiko) and November 10th in Bresnitsa (Vatochori). The 3rd Division marches in the Village of Zelenich (Sklithro) on November 10th and Zagorićani (Nov. 11) and Kastoria (Nov. 12).

- At Monastir, the battle lasted from 16 to 19 November and ended in a Turkish defeat. From then on, the League’s victory was sealed.

November 10th the Greek Army enters Zelenich

At first sight the Greek army is welcomed into Zelenich as liberators, but this soon changes within a few hours. Soldiers systematically go from house to house confiscating all the Macedonian liturgical books, bibles and any books, written material, postcards, and pictures that contained Cyrillic writing. They also terrorize the villager by threatening to do great harm on them if they do not convert back to the Greek Patriarchist church. We do not have any information as to what the Greek soldiers did to our Muslim villagers their stay in Zelenich.

Greece’s, Serbia’s, and Bulgaria’s military and paramilitary forces murdered and plundered unarmed Muslim inhabitants and sent even more fleeing in terror. Although precise overall figures for Macedonia in the First Balkan War do not exist, it seems that non-combatant Muslim deaths from attacks and from starvation and disease resulting from their dispossession reached at least into the tens of thousands,

while hundreds of thousands more became refugees. That fact that the Christians and Muslims lived in harmony maybe the Christians prevented this from happening. We do not know though for sure.

The Greek 5th Division was to march to Zagorićani the next day and in the evening of Sunday November 10th, word soon gets out that the soldiers are to burn down St. Georges church the next day. Before dawn, on Monday November 11, 1912, all the women in the village encircle the church and form a human chain. On their way out of the village, the Greek 5th Division meets the women of Zelenche and are told that if they want to burn the church down, they are going to have to kill all the women first.

The story passed on from one generation to another is that the Greek 5th Division did not get to burn down St. Georges church but took the icons of St. Cyril and Methodius and placed then on the ground of the road outside the church. The soldiers then stomped on the icons as they marched out of the village on their way to Zagorićani all the while threatening the village with violent reprisals if the people did not convert to becoming Greek. Soon after the departure of the new occupiers, there was a great uproar of celebration as the women saved their sacred church.

The violence committed by the Greek military and paramilitary forces and the threats of more violence towards all the inhabitants of Greek occupied Macedonia were very evident. Macedonians were free of one long time oppressor and were now being occupied by another. According to Greek sources, the occupiers celebrated the “spontaneity” and rapidity with which the vast majority of former followers of the Exarchate returned to what they called, “the Mother Church.” This was not the case in Zelenich and many other villages and towns.

People did not willingly give up their treasured liturgical books, they were threatened with harm/death. The Greek military and paramilitary terror tactics were reported in the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars. More on the report further down in this section.

Even Stephanos Grammenopoulos, resident of the village of Zelenich in Greek occupied western Macedonia and a long-time local supporter of the Greek cause, proudly reported how his “Bulgarian” co-villagers converted after the arrival of the Greek army. Afterwards they spontaneously gathered the Bulgarian books of the church and delivered them to the head of the detachment… , who reportedly took them to His Holiness Bishop Ioakim of Kastoria. [The Bulgarians] who followed along were accepted into the embrace of the Mother Greek Orthodox Church, forgiven for their error which resulted either from fear or from compulsion.

The village oral history paints a different picture of this incident and the person called Stephanos Grammenopoulos. Although Grammenopoulos was a local villager, Greek government officials often most likely made up the so-called phenomenon of the “willing and spontaneous conversion” of the people in Zelenich and the rest of Greek occcupied Macedonia. The propaganda being reported by the Greek Governor-General of Macedonia, Stephanos Dragoumis was that … in the countryside and the small centres in general… the numbers of schismatics are disappearing as the Exarchists have turned out in multitudes along with the [Exarchist] priests, spontaneously declaring repentance, delivering over churches, schools and Slavic liturgical books and accepting pardons and blessings from the Orthodox Bishops and from the Patriarchate. This was in fact the narrative the Greek government wanted to report, in order to justify their claim over the areas of Macedonia that the Greek military occupied.

The truth comes out later in the same report when, Dragoumis suggested that state coercion remained an option to encourage those inhabitants whose conversion might not be so “spontaneous.” He reported that “in the urban centres majorities have returned in every way to the Greek traditions to which they are unmistakably inclined.” But a minority had failed to do so “only out of timidity, as they await to be convinced that the violence of the dismantled Bulgarian organization would not again bring about an alteration of the existing situation.” Dragoumis proposed that this timid minority would be quickly reassured “if we remand in custody those who subscribe to the wiles of externally lurking politics of intervention.”

Not only does Dragoumis actually state what the Greek military was doing, he also asks Patriarchist Macedonians to inform on their fellow villagers if they do not convert to becoming Greek. The Greek military personnel, police, and church notables, who openly welcomed the conversion of former followers of the Exarchate to the Patriarchate, also provided the presence capable of making good on the threat of repression for those who appeared suspicious. This combination of factors sent a strong signal to the local inhabitants.

Having to “repent” for the “error” of longstanding attendance at their Macedonian family parish church and exchange a Slavonic liturgy close to their spoken language for the Greek liturgy would have been painful experiences for all indigenous Macedonians. In Zelenich, even the use of St. Demetrius for the four Patriarchist families that used the church had service using the spoken village language. Villages did not have a choice of keeping their liturgical books, they were taken by force and burned in front of their eyes.

The actions of Stephanos Grammenopoulos after the second Balkan War (1913) are very ironic since he was involved in the village “Bloody Wedding” by helping the Greek paramilitary group to murder 22 villagers. After the cessation of hostilities from the Second Balkan War, Grammenopoulos wrote a letter to the Greek Governor-General of Macedonia to report that “during the entire period of the war the Bulgarians (Macedonians) of our village did not engage in plunder or pillage.” Indeed, Grammenopoulos added, all residents displayed their utmost willingness to help the Greek forces. It is very comical that he calls his own relatives – Bulgarians!!!

He implored the Governor-General in advance to order his authorities not to arrest anyone in his village. “If any arrests should occur, they will have occurred unjustly,” he insisted. Once again, how can someone who is hated now try to protect those who despise his support of Greek terror? Was he and those in his family trying to make amends with those that they betrayed? Krvava Svadba (Bloody Wedding) had only occurred 9 year earlier and he and three other Grammenopoulos family members served a year in a Monastir (Bitola) jail for their crime.

It gets even more ironic when not long afterwards, Grammenopoulos traveled to Salonika and tried to meet with the Governor-General. Unable to secure a meeting, he wrote him a letter from his hotel to ask the release from prison of a group of men from his neighbouring village, Aetos. Grammenopoulos began by reminding the Governor-General of his family’s long service in the struggle for Hellenism.

On this basis of trust, he presumed to establish with the Governor-General, he insisted that he could tell quite well who the “bad Bulgarians or bad Macedonians” in his area were. Of the sixteen residents of Aetos arrested as “suspect Bulgarian supporters” by Greek authorities three months before (including a priest named Papa Ilias), Grammenopoulos asserted that eight had been detained completely in error. They had been “Greeks all along”; indeed, the father of one of them “was hacked to pieces long ago by a Bulgarian Committee [Komitatou],” while the others had also long suffered from abuses by Bulgarian armed bands.

Grammenopoulos assertions about so called “Bad Bulgarians” (Macedonians who supported the Bulgarian cause) were “Greeks all along,” is so far from the truth that it is laughable. Both Zelenich and Aetos were supporters of the Bulgarian Exarchist church but also staunch IMRO supporters and in favour of a free and independent Macedonia. Once again, the question that must be asked is, “how can someone who proclaimed and professed to be a Greek supporter, try to protect Macedonians who did not support the Greeks cause?

Grammenopoulos pleaded for the eight “so-called Greeks” to be released, but he then went a step further by stating that: “The others remaining had always been Bulgarians, but now the entire village [including those formerly adhering to the Bulgarian Exarchate] has come around and the Holy bishop of Kastoria celebrated the liturgy and blessed them and forgave them,” he noted. He named only the Exarchate priest, Papa Ilias, as “worthy of the gallows; he is the one who has committed all the crimes and was the key to Bulgarianism in Aetos.” This incident shows one aspect of the environment created at the beginning of the assimilation process the Greeks used and how some Macedonians began proclaiming themselves and their fellow villagers Greek.

After the Second Balkan War, this so-called Hellenic patriot – Grammenopoulos, is portrayed as risking all to protect the Bulgarians (Macedonians) in his village as well as all but one imprisoned from a neighbouring village. Even though he was a rival to his own ethnicity, he does show a real notion to a genuine national identity in an extreme way of supporting local solidarity or is portrayed as showing the unity. The economic and cultural development would become important priorities for residents of the towns and villages of former Ottoman Macedonia.

It seems that Grammenopoulos had a strong interest in maintaining the social stability of Zelenich but with a new occupier. However, widespread acts of violent retribution would generally serve to undermine such stability. By fingering only, the Exarchate Macedonian priest as “the key to Bulgarianism in Aetos,” Grammenopoulos would eliminate the one person he saw as the most important agent of past instability – and potential cause of future instability – in his local area.

This was very apparent when soon after their entrance to Zelenich, the Greek occupying forces arrested all the teachers in the village and placed them in jail for being teachers. Yes, the village had two Bulgarian schools and one Greek school but this was far from being way to treat people who fought against the same enemy. The teachers in Zelenich were V. Pliakov (villager), Bl. Tipev, G. Drandarov, L. Dukova, A. Hristova, B. Karamfilovich and D. Ghizova (villager).

Villagers chose to send their children to the school of their choice under their own free will. Such tactics were also conducted by the Serbians and Bulgarians in the Macedonian occupied territories of Vardar and Pirin. The assimilation policies were very assertive, aggressive, and threatening as the occupiers were ethnically cleansing the identity of Macedonians and did not want any revolts occurring in their newly acquired territories.

The true identity of the so-called Hellenic Patriot Stephanos Grammenopoulos

His real name was Stefo Vangeleff and was married to one of the Grameni (Gramenopoulos) women. Stefo was the person who tricked a young pregnant girl to open the door of the house where the wedding of the niece of the village priest was taking place. Stefo spoke to the girl in Macedonian and as she began to open the door, he pushed his way in and all in one motion stabbed her in the belly, her pregnant belly. He and the rest of the Greek paramilitary terrorists then went on a rampage and ended up killing 22 people. The crime made the news all over the world and several men were prosecuted and sentenced to serve time in a Monastir jail. They ended up only serving one year and after their release, Stefo Vangeleff became Stephanos Grammenopoulos. The name Gramenopoulos was also a changed name but the time of the change from Grameni to Gramenopoulos is uncertain, and most likely it took place when the Greek Anti-Macedonian Agenda was set in motion after 1897.

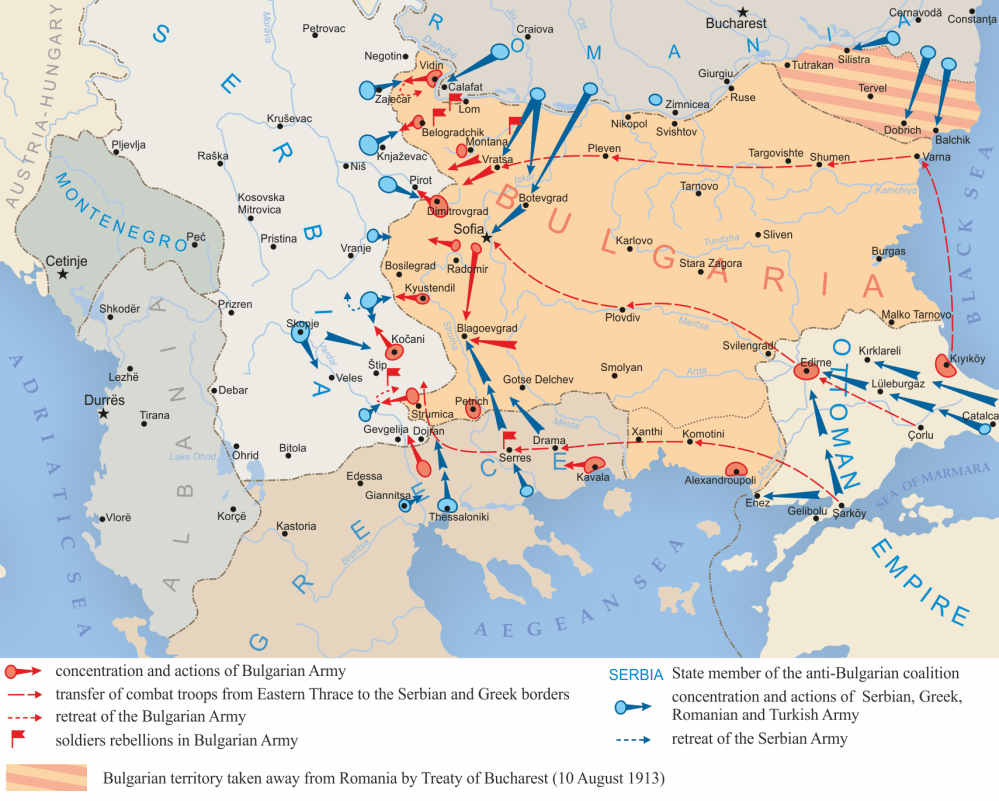

Origin of the Second Balkan War

The signing of the Treaty of London, on the 30 May 1913, officially ended the war between the Balkan League and the Ottoman Empire. The Empire was forced to concede a vast territory. “The Ottomans ceded all lands east of a straight line drawn across eastern Thrace from the Aegean port of Enos (Turkish, Enez) to the Black Sea port of Midia (Turkish, Midye)”. The empire also relinquished Crete, the Aegean Islands and Albania, leaving it to the Powers to decide the future of the latter two. They decided to establish Albania as an independent state and to leave the Aegean Islands and Crete (which would obviously go to Greece) to the League.

In spite of all the wheeling and dealing that went on during the conference the resolutions left all parties dissatisfied. Serbia was dissatisfied with losing the Albanian territory and not having access to the sea so, she asked Bulgaria to grant her access to the Aegean Sea via Saloniki. Greece was not happy with Bulgaria’s invasion and annexation of Endrene (Adrianople). So, to balance her share Greece wanted Serres, Drama and Kavala as compensation. Bulgaria, frustrated with not achieving her “Greater Bulgaria Dream” was bitter about Russia deserting her during the London Conference negotiations.

Seeing that Bulgaria was not going to budge and the fact that neither Greece nor Serbia alone could take on Bulgaria, should a conflict arise, Greece and Serbia concluded a secret pact of their own to jointly act against Bulgaria. In short, the objective was to take territory from Bulgaria west of the Vardar River, divide it and have a common frontier. After stumbling upon this Greek-Serbian pact, despite Russian attempts to appease her by offering her Saloniki, Bulgaria remained bitter and in a moment of weakness, was lured away by Austria. By going over to Austria, Bulgaria in effect broke off all relations with the Balkan League.

The Balkan states’ rapid victories over the Ottoman Empire did nothing to resolve the longstanding disputes between Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia, each of which now occupied a portion of Macedonia. The Second Balkan War was thus a war centred in Macedonia over the spoils of the Balkan states’ victory. Bulgaria, frustrated for not having been granted the territories mentioned in the treaty signed on March 1912 with Serbia, attempted to compensate for this loss by claiming Salonika, also coveted by the Greeks. For several months, Bulgaria displayed its ambition to control almost all of Macedonia.

The Serbs and the Greeks no longer wanted to cede Vardar and Aegean Macedonian territory to Bulgaria. Serbia argued that Albania’s independence invalidated the provisions of the treaty. The Serbs, eager to establish their authority in the conquered territories, forced, the Macedonian inhabitants to convert to the Serbian church. Greece eager not to give up her gains in Western Macedonia and Salonika also began to terrorize Macedonians as their military entered each town and village. “The population that had their confessional freedom as part of the Ottoman Empire, now started being assimilated both in a religious and ethnic sense.” On 1 June 1913, Serbia, and Greece, feeling threatened by Bulgaria’s claims on Monastir and Salonika, decided to form an offensive and defensive alliance against the Bulgarians.

On 29 June 1913, the Bulgarian army, unprovoked, launched an attack on Serbian positions, effectively declaring war on Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro. Preferring the element of surprise, Bulgaria turned on her former allies and renewed the conflict, officially turning the Macedonian mission from “liberation” to “occupation”. The bloody fight was short lived as Roumania, Montenegro and Turkey joined Greece and Serbia and dealt Bulgaria a catastrophic blow.

Moreover, the Bulgarian troops were exhausted from fighting for such a long time as they were under attack from all sides. The Bulgarians preferred not to defend their territory when Roumania launched an attack from the north. On 12 July, the Ottoman army entered the field to retake Adrianople. On 13 July, the Bulgarian Prime Minister resigned, and he was replaced by a new government which immediately appealed to the Powers for help in stopping the attacks. Russia and Austria-Hungary intervened, and The Treaty of Bucharest was signed on 10 August, officializing the division of Macedonia into three parts. The biggest going to Greece called Aegean Macedonia (50%); Serbia – Vardar Macedonia (40%); and Bulgaria – Pirin Macedonia (10%).

The Macedonians fared worst in the conflict mainly due to their own enthusiasm. One faction misinterpreted Macedonian assistance to another, as disloyalty. As front lines shifted positions, Macedonian citizens were exposed to the various factions. Those Macedonians that assisted one faction were butchered by another faction for showing sympathy to the enemy. This genocidal tragedy was committed in a relatively short time and by those who marched in and were welcomed as “liberators”.

The armistice and peace treaty signed between Roumania, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia in August 1913 in Bucharest again redrafted the map of Macedonia without Macedonian participation. These new boundaries imposed an artificial sovereignty upon the Macedonian people. It went so far as to further instill one minor change in 1920 in Albania’s favour by giving it the territory called “Mala Prespa,” further dividing Macedonia into four parts.

The Treaty of Constantinople was signed on 30 September 1913 between Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. During these negotiations, the Ottoman Empire refused to cede any territory it had taken during the Second Balkan War, leaving only a small strip of territory to Bulgaria north of Adrianople.

Demographic Engineering

Nationalism was a key element of the conflicts in the Balkans. The Macedonian territory, situated in the middle of the Balkan states, became the target of their territorial ambitions. Their claims were legitimized by the number of adherents in the churches headed by each state and their rivalry over these figures continued even after the end of the first Balkan War, while the states were still trying to partition the territory.

The Balkan Wars of 1912-13 and the division of Macedonia made a lasting impact on the relationships between the Balkan states. However, the battles for Macedonia were preceded by many lesser battles in which the churches and schools were on the battlefields, while the weapons used were the cross and schoolbooks. These attempts for spiritual and intellectual conquering of the Christian peoples in Macedonia on the part of their Balkan neighbours were regularly followed by statistical records of the newly found Greeks, Bulgarians, and Serbians. The signing of the Bucharest Treaty of 1913 sealed the division of Macedonia and set in motion the aggressive assimilation of the Macedonian peoples in each of the divided regions.

The division of Macedonia was sanctioned by the European Powers as they each sought to increase their influence in the region. Their meddling or lack of meddling in keeping the status quo in the affairs of the people of Macedonia from the Berlin Treaty of 1878, right up to the Bucharest treaty of 1913 was 35 years of terror for a people who fought to be freed from bondage from one oppressor to the assimilation of another oppressor. The Macedonian people were victims of not only the Ottoman policies but more so of the terrorist tactics of the Bulgarians, Serbians and the Greeks. These expansionist tactics used methods which violated every aspect of human life. They attacked peoples spiritual, intellectual, emotional, physical, cultural, social, political and economical well being. This was just the start of systematic generational discrimination with assimilation policies that is an example of what is called today, “Demographic Engineering.” The conversion of the Macedonian indigenous people to be moulded into becoming new Greeks, Serbians and Bulgarians.

The people from geographic Macedonia, were called Bulgarians, because they chose to belong to the Bulgarian Exarchist Church (millet) for their religious affiliation. Ethnically, they considered themselves Macedonian well before this time period and they fought for an independent and autonomous Macedonia just as their Balkan neighbours of Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria did previously. They even supported each of these states in their own quest for freedom from the Ottoman yolk. But, when it came to support a free and liberated Macedonia, Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria chose to fight and destroy the very essence of what it meant to have a Macedonian identity. The terror in the Balkans which occurred between 1878 and 1913 was in fact the concerted efforts taken by Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria to wipe out – commit GENOCIDE – against Macedonians. The “Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars,” was just the “tip of the iceberg” into the atrocities committed in Macedonia.

The Balkan Wars and “Genocide”

The “Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Washington D.C., 1914) opened the worlds eyes into the ethnic cleansing and crimes committed against the Macedonian people. Even though the report identifies the majority of the atrocities being committed on Bulgarians, it is those Macedonians who converted to following the Bulgarian Exarchist Millet from the Greek Orthodox Millet, that have been identified as Bulgarians. and not actual ethnic Bulgarians.

After 1767, there were only two Millets, a Muslim one and a Christian (Greek) one. All Christians in Ottoman Europe, Serbians, Bulgarians, Macedonians, and Romanians were identified as Greeks. Once the Serbians, Bulgarian and Romanians gained autonomy/independence they also gained the right to have their own millet (church). This allowed them to administer their own churches with liturgies given in each of their own languages.

Bulgaria gained this autonomy to administer their own church (Exarchist) in 1870, and after this date, Macedonian communities were given the right to join the Exarchist church so they joined on mass because they were being exploited by the Greek Orthodox Patriarchy. Thus, they started being called Bulgarians not because they were ethnically Bulgarian but because they joined this schismatic church and began being labelled as Bulgarians for their religious affiliation not their ethnicity.

The Bulgarians, looking at expanding their territories and creating a “Greater Bulgaria” took advantage of the millet religious system to count Macedonians as Bulgarians and claim the territories they lived in as their own. Macedonians were also claimed by the Greeks and Serbians for their greater territorial aspirations too. Thus began the competition over Macedonia as these plans were put into action after the Berlin Treaty of 1878. The competition over Macedonia was first against the indigenous Macedonians and their organizations that fought for autonomy.

At first, Bulgaria having gained their autonomy and independent church, courted Macedonians to join them in their fight against not only the Ottoman Empire , but also, the Greeks and their Patriarchy in Istanbul. Thousands of Macedonians started working, becoming educated and moving to Bulgaria gaining independence and a freedom that did not exist in Ottoman Macedonia. A diaspora developed and supported an independence movement which became official in 1893 – as the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). The Macedonian revolutionary independence movement was soon split in two factions, the “Centralist” and the “Supremacist” the latter being infiltrated with Bulgarian teachers and officers who used this movement to eventually gain Bulgaria’s independence in 1908.

The Ottoman Millets and Ethnicity

The Turks classified the population, not by language or race (ethnicity), but by religion. A Greek is a member of the Orthodox Church who recognizes the Patriarch of Constantinople; a Bulgarian, on the other hand, is one of the same religious faith who recognizes the Exarch; and since the Serbians in Turkey had no independent church but recognized the Patriarchate they were often, as opposed to Bulgarians, called Greeks. Race/ethnicity, being thus merged in religion – in something that rested on the human will and not on physical characteristics fixed by nature or ethnic/cultural characteristics set by history – were in the Balkans changed as easily as religion.

“A Macedonian would be called a Greek to-day, a Bulgarian to-morrow, and a Serbian next day “

Millets were the only legal religious entities authorized by the Sublime Porte (Central Government of the Ottoman Empire). By the time of the Balkan Wars, there were five official European Millets – one Muslim; and four Christian; the Romanian; Serbian; Bulgarian; and Greek. If you happened to belong to an ethnic community outside the official Millets, you could only join one of the official four Christian Millets authorized in the empire. This meant that Vlachs, Albanians, and Macedonians got identified according to the church millet that was authorized in the region, town or village. In the case of the Macedonian people, they chose the Bulgarian Millet and thus Macedonians were labelled as Bulgarians. Just as those Macedonians who were threatened to join the Greek Patriarchate went from being called Bulgarian to being called Greek.

The more bishops, churches, and schools a nationality could show, the stronger its claim on Macedonia and Macedonians when the Turk would be driven out of Europe!

It is logical to understand how the nationalist of yesterday used ethnic cleansing (demographic engineering) to create their expanded states out of Ottoman Macedonia. They used religion as a marker for ethnic identity in creating a false homogeneous citizenship out of force. But, it is very close-minded/biased for scholars and academics today not to be able to distinguish between a manufactured religious identity and an ethnic identity. To actually go as far as stating that the majority of the Christian people of Macedonia who were victimized during the Balkan Wars were Bulgarian because the reports identify them as such. Academics of today should be able/willing to see through the political and nationalistic veil that still covers their eyes and cast a clearer, fair and equitable narrative for the victims – the Macedonians of Ottoman Europe in the Balkans.

Despite mutual recriminations and declarations of innocence, none of the nations involved in the Balkan Wars was blameless in regards to the numerous violations committed by combatants and noncombatants in the course of the conflict. The majority of those displaced/killed were Macedonians who they were counted as their own casualties. As the final report of the Carnegie Commission stated in the spring of 1914, all of the warring parties were to a greater or lesser extent involved in widespread violations of international humanitarian law.

The “Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Washington D.C., 1914) opened peoples eyes into the ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity that took place towards the Macedonian people.

- The invading nationalist armies committed atrocities against civilians on Ottoman territories. In general, the report issued by the Carnegie Institute in 1914 presents a dispassionate account of these events.

- The Carnegie Relief Commission, dispatched to the Balkans in late 1913, reported the incredible story of human suffering. In Macedonia alone, 160 villages were razed leaving 16,000 homeless, several thousand civilians murdered, and over 100,000 forced to emigrate as refugees.

- The violent events of the Balkan Wars were the start of the modern age phenomenon of “ethnic cleansing,” in which warring parties pursuing the goal of ethnic homogeneity in a recently acquired territory expel ethnic groups by means of threats and violence.

- Disregarding the stipulations of the Hague Convention of 1907, which contained regulations for protection of civilian populations and humane treatment of prisoners of war, the armies engaged in the Balkan Wars committed atrocities against each other and Macedonian civilians by forcing hundreds of thousands of civilians to leave their homes and communities to find safety in the nation-state that would accept them if they rescinded their identity and accepted the identity of the new nation state.

- The methods utilized to carry out this policy of ethnic cleansing—meant to cause unwelcome parts of the population to flee—included looting, rape, and massacres; systematic destruction of private, public, cultural, and religious property; and the burning of entire villages to the ground.

- The main perpetrators of this violent expulsion were irregular troops that had waged a relentless guerilla war against each other in Ottoman Macedonia since the end of the nineteenth century and thereby amassed considerable experience in terrorizing civilians.

- These forces inflicted horrific violence on non-combatants, even though the very first article of the Hague Convention designated “militias” and “voluntary corps” as combatant parties, thereby subjecting them to the laws and conventions of war in their activities.

- In the majority of cases of use of force against civilians, these paramilitary units did not act unilaterally, but rather in coordination with the commanders of regular troops and local authorities, or at least with their acquiescence.

- During the First Balkan War, it was primarily the Muslim populations in Kosovo, Macedonia, and Thrace that were victimized by ethnic cleansing. After fleeing the areas taken by Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria, they were evacuated to Istanbul and Asia Minor. Despite this wave of refugees, more than 200,000 Muslims are estimated to have died from violence, hunger, or illness in the First Balkan War.

- The Second Balkan War began with Bulgaria’s attack on Serbian and Greek defense positions on June 29, 1913, and by August had ended in the aggressor’s defeat. Despite its short duration, it was even more consequential, in terms of human casualties, than the preceding conflict between the Balkan League and the Ottoman Empire.

- Now it was Christians in the disputed areas who became the targets of ethnically motivated forced migration. In the formally multicultural Thessaloniki, for example, only a small remnant of the Bulgarian (Macedonian) community remained, and it was exposed to strong Hellenic assimilation pressure immediately after the Greek capture. The majority, in contrast, were either deported from the city on a Bulgarian steamer or arrested by Greek security forces.

- Bulgaria and Serbia also systematically implemented forced migration with each other and with the Greeks. It is noteworthy that the Greek state relied on local Turkish militias’ assistance to carry out ethnic cleansing. During the Second Balkan War, the Ottoman Empire also participated in atrocities perpetrated against civilians for purposes of ethnic cleansing. In particular, in Eastern Thrace the Ottoman recapture of Adrianopel/Edirne led to the expulsion of Bulgarians (Macedonians) from that region. Local ethnic Greeks supported the Ottomans by expelling the Bulgarians (Macedonians).

- According to Paul Mojzes, ethnic cleansings during the Balkan Wars were so excessive that they can be characterized as genocidal, applying the current UN definition of genocide as well as the relevant judgments of the international Yugoslavian tribunals.

- Today, the final report of the Carnegie Commission— which, as mentioned, spread the responsibility for war crimes committed against civilians across the warring parties and it represents the most important resource on the dissolution of the violence that took place in the course of the Balkan Wars by splitting Macedonia and its people into three different nation states. This in essence continued as generational ethnic cleansing now called demographic engineering.

The Bucharest Peace Treaty of August 10th, 1913

The Bucharest Peace Treaty presented the end of the two Balkan Wars from the 1912/1913 period, by which the dividing of the territory of Macedonia among its Balkan neighbours Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia, was sanctioned. The nationalistic campaigns of the Balkan countries resulted in erasing Macedonia from the Balkan map.

The Bucharest Peace Treaty represents a unique international agreement which was not signed by all of the big powers and which in a great amount was against their interests. The agreement itself has ten articles including twelve protocols with a large amount of data relating to the annexations. Click on the link below to view the treaty.

At the conclusion of the Bucharest agreement more bilateral agreements followed. For example, an agreement between Greece and Turkey was signed by which the two states agreed to exchange and resettle populations. The Macedonian and the Muslim Macedonian populations from Aegean Macedonia were to be moved to Asia Minor while the Greek refugee population from Asia Minor was to be transferred to Aegean Macedonia.

However, the great powers did not take into consideration the demands of the Macedonian people, who from more associations, especially from Russia and Switzerland, intervened to save its identity, and the unity and integrity of the Macedonian territory.

On March 1, 1913, the Macedonian colony in St. Petersburg sent a memorandum on the independence of Macedonia to the conference of Great Powers in London, along with a geographical-ethnic map of Macedonia made by Dimitrija Čupovski.

On June 7, 1913, a second memorandum of the Macedonians was sent to the governments and peoples of the combatants of the Balkan Wars, stating that “in the name of natural right, in the name of history … Macedonia is inhabited by a homogeneous population having its own history, and hence the right to self-determination. Macedonia is to be an independent state, within its natural borders. The Macedonian state is to be a separate equal unit of the Balkan League, with its own church established on the foundations of the ancient Ohrid archbishopric”, requesting that a people’s representative body be convened in Salonica. This memorandum was signed by members of the Macedonian colony in St. Petersburg.

Despite the obvious fact that in the partition of Macedonia a nation had been divided. The 35 years of foreign paramilitary and military interventions since the Conference of Berlin in 1878 had confirmed the division with the decisions of the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest.

Having failed to achieve independence in 1903, the Macedonians, now divided, were left to the fate of their new masters. Greece took 51% of Macedonia (Aegean Macedonia) and renamed it “Northern Greece”; Bulgaria annexed 10% (the Pirin region) and abolished the Macedonian name and Serbia took over 39% (the Vardar region) and renamed it “South Serbia”.

Serbia and Greece agreed on the newly formed Greek-Serbian border so that there would be “only Serbs to the North and only Greeks to the South” and no “Macedonians” on either side. By this agreement began the destruction of Macedonia’s geographic, natural and ethnic unity.

An intensive denationalization campaign was carried out in all three parts of Macedonia in order to impose foreign identities upon the Macedonian population, the kind that suited the interests of the controlling states. In Vardar Macedonia the Serbs labeled the Macedonians “South Serbs”, in Aegean Macedonia the Greeks labeled them “Slavophone Greeks”, while in Pirin Macedonians were simply called Bulgarians.

With the peace agreement in Bucharest (August 10, 1913), Macedonia is divided among its neighbours Balkan countries. Two years later (1915 – 1918), its territory continues to be an arena of military devastation and destruction. Being at the centre of the war, Macedonia became an interesting sphere again for the Balkan and European military-diplomatic and political interests that had been dictated for more than a century by the five great powers: Austria-Hungary, Great Britain, Germany, Russia and France.

Sources Used:

Ahmad, F. (2014). War and nationalism: The Balkan wars, 1912-1913, and the Sociopolitical implications edited by M. Hakan yavuz and ISAL BLUMI, foreword by Edward J. Erickson. Journal of Islamic Studies, 26(1), 78-80. https://doi.org/10.1093/jis/etu057

Anastasovski, N. (2008). The contest for Macedonian identity 1870-1912. Pollitecon Publications.

Anderson, D. S. (1993, December 17). THE APPLE OF DISCORD: MACEDONIA, THE BALKAN LEAGUE, AND THE MILITARY TOPOGRAPHY OF THE FIRST BALKAN WAR, 1912-1913,. apps.dtic.mil/. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA284241.pdf

Argolikivivliothiki. (n.d.). The Balkans before the First Balkan War [Map]. Argolikivivliothiki.gr. https://argolikoslibrary-files-wordpress-com.translate.goog/2018/01/cf84ceb1-ceb2ceb1cebbcebaceaccebdceb9ceb1-cf80cf81ceb9cebd-ceb1cf80cf8c-cf84cebfcebd-cf80cf81cf8ecf84cebf-ceb2ceb1cebbcebaceb1cebdceb9.jpg?_x_tr_sl=el&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=sc

Argolikivivliothiki. (2018, November 1). 1912 Map of Allied Forces [Map]. http://www.argolikivivliothiki.gr. https://argolikoslibrary-files-wordpress-com.translate.goog/2018/01/11-aladjem.jpg?_x_tr_sl=el&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US&_x_tr_pto=sc

Avidius. (2010, August 2). Bulgarian military operations during the First Balkan War [Map]. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_Balkan_War#/media/File:Bulgarian_Army_FBW.JPG

Balkan wars. (n.d.). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Balkan-Wars

Billkos. (2012, October 10). Balkan Wars 1912-1913. Ιστορικά Καστοριάς. https://istorikakastorias.blogspot.comhttp://istorikakastorias.blogspot.com/2012/12/blog-post.html

Boeckh, K., & Rutar, S. (2018). The wars of yesterday: The Balkan wars and the emergence of modern military conflict, 1912-13. Berghahn Books.

Boeckh, K., & Rutar, S. (2018). The wars of yesterday:. The Wars of Yesterday, 3-18. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvw04j9c.5

Boissière, C. (2008, November 2). Greek military operations during First Balkan War [Map]. commons.wikimedia.org. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gr%C3%A8ce_1ere_Guerre_balkanique.png

Bregu, E. (2013, October 1). The causes of the Balkan wars 1912-1913 and their impact on the international relations on the eve of the First World War. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/291040183_The_Causes_of_the_Balkan_Wars_1912-1913_and_their_Impact_on_the_International_Relations_on_the_Eve_of_the_First_World_War

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (Invalid Date). Balkan Wars. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Balkan-Wars

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (1914). Carnegie-report-on-the-Balkan-Wars.pdf. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/33147425/Carnegie_Report_on_the_Balkan_Wars_pdf

Contor, Lucas. Traduction partielle et comment e de l’ouvrage “The Balkan Wars : British consular reports

from Macedonia in the final years of the Ottoman Empire”. Facult de philosophie, arts et lettres, Universit catholique de Louvain, 2020. Prom. Arblaster, Paul. http://hdl.handle.net/2078.1/thesis:23979

Despot, I. (2019, January 1). The Balkan wars: An expected opportunity for ethnic cleansing. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/40225532/The_Balkan_Wars_An_Expected_Opportunity_for_Ethnic_Cleansing

Dodovska, I., & Popovska, B. (n.d.). The Bucharest Peace Treaty o f 1913: a Historical and Tega/Analysis. PERIODICA. https://periodica.fzf.ukim.edu.mk/mhr/MHR2(2011)/MHR02.16%20Popovska,%20B.,%20Dodovska,%20I.%20-%20The%20Bucharest%20Peace%20Treaty%20of%201913.%20A%20Historical%20and%20Legal%20Analysis.pdf

Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Balkan wars. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Balkan-Wars

Geppert, D., Mulligan, W., & Rose, A. (2016). The wars before the Great War: Conflict and international politics before the outbreak of the First World War. Cambridge University Press.

Hall, R. C. (2002). The Balkan wars 1912-1913. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203138052

Hall, R. C. (2014, October 8). Balkan wars 1912-1913 | International encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1). 1914-1918-Online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1). https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/balkan_wars_1912-1913/2014-10-08

International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars. (1993). The other Balkan wars. A 1913 Carnegie endowment inquiry in retrospect, with a new introduction and reflections on the present conflict by George F. Kennan.

Jackanapes. (2006, August 30). The Balkan boundaries after 1913 [Map]. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Balkan_War#/media/File:The_Balkan_boundaries_after_1913.jpg

Kandi. (2018, February 16). Second Balkan War [Map]. Wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Balkan_War#/media/File:Second_Balkan_War.png

Kandi. (n.d.). Map. AYearofWar.com. http://ayearofwar.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Map_of_the_First_Balkan_War.jpg

Karakasidou, A. N. (2009). Fields of wheat, hills of blood: Passages to nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990. University of Chicago Press.

Kolev, V., & Koulouri, C. (Eds.). (2009). Balkan wars (2nd ed.). Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe. http://www.pollitecon.com/Assets/Ebooks/Workbook-3-The-Balkan-Wars.pdf

Macedonia 1912-1918. (n.d.). https://macedonia1912-1918.blogspot.com/

Melas, S. (2012, 24). (2nd Balkan War) 2ος ΒΑΛΚΑΝΙΚΟΣ ΠΟΛΕΜΟΣ. ΠΟΙΜΕΝΙΚΟΣ ΑΥΛΟΣ. https://pluton22.blogspot.com/2012/10/2.html

Melas, S. (2012, October 24). The friendships of the first alliance against the Ottomans began to fade [Photograph]. pluton22.blogspot.com. https://sklithro-zelenic.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/9d28d-snimka1.jpg

Melas, S. (1913). Macedonian Voivoida Yane Sandanski Macedonian force with a part of the Bulgarian Army in 1913 “going down” to Drama [Photograph]. Pluton22.blogspot.com. https://sklithro-zelenic.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/c0a7e-sandanski2.jpg

Papaioannou, S. S. (2012). Balkan wars between the lines: Violence and civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918.

Ray, M. (n.d.). Balkan wars. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Balkan-Wars

Radin, A. M. (1993). IMRO and the Macedonian question (p. 326). Kultura.

RHM Burgas. (n.d.). Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps during the Balkan War [Photograph]. Burgasmuseums.bg. https://www.burgasmuseums.bg/en/encdetail/macedonianadrianopolitan-volunteer-corps-119

Sowards, S. W. (1997, February 4). The Balkan causes of World War I. lib.msu.edu. https://staff.lib.msu.edu/sowards/balkan/lect15.htm

Schurman, J. G. (1914). The Project Gutenberg E-text of the Balkan wars, 1912-1913, by Jacob Gould Shurman. Free eBooks | Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/36192/36192-h/36192-h.htm

Stefov, R. (2003, February). MACEDONIA What went wrong in the last 200 years? Pollitecon Publications. https://www.pollitecon.com/Assets/Ebooks/Macedonia-What-went-wrong-in-the-last-200-years.pdf

Tokay, G. (2018). Ottoman diplomacy on the origins of the Balkan wars. The Wars of Yesterday, 93-112. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvw04j9c.7

Tokay, G. (2013). Gul tokay, ‘ the origins of the Balkan wars: A reinterpretation’, in H. Yavuz and I. Blumi (EDS.), war and nationalism the Balkan wars, 1912–1913 and their Sociopolitical implications ( Utah: Utah University press, 2013), pp.176-196. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/20481541/Gul_Tokay_The_Origins_of_the_Balkan_Wars_A_Reinterpretation_in_H_Yavuz_and_I_Blumi_eds_War_and_Nationalism_The_Balkan_Wars_1912_1913_and_Their_Sociopolitical_Implications_Utah_Utah_University_Press_2013_pp_176_196

Tsoutsoumpis, S. (2020). The lords of war: Violence, governance and nation-building in north-western Greece. European Review of History: Revue européenne d’histoire, 28(1), 50-73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13507486.2020.1803218

Weinreb / Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. (1914). Territirial Aspirations of the Balkan States 1912 [Map]. Wikimedia. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cc/Territorial_aspirations_of_the_Balkan_states%2C_1912.jpg

Whitehead, F. (2017, December 31). The first & second Balkan war. A Year of War. https://ayearofwar.com/wwi-diary-balkan-war/

Yavuz, M. H., & Blumi, I. (2013). War and nationalism: The Balkan wars, 1912-1913, and their Sociopolitical implications. The University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Yosmaoğlu, İ. (2013). Blood ties: Religion, violence and the politics of nationhood in ottoman Macedonia, 1878– 1908. Cornell University Press. Zoupan. (1908). Chetniks with Ottoman officers in Skopje during Young Turk Revolution [Photograph]. Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/43/Chetniks_with_Ottoman_officers_in_Skopje_during_Young_Turk_Revolution_%281908%29.jpg