Following the partition of Macedonia in 1913, Greece acquired the largest portion, known as Aegean Macedonia. Instead of recognizing the region’s Macedonian identity, Greece redefined it as part of “Northern Greece” and systematically worked to erase its ethnic and cultural distinctiveness. Before the annexation, the majority of the population in Aegean Macedonia spoke Macedonian, a fact recognized by all sources except Greek ones. However, through a combination of forced expulsions, population re-settlements, cultural suppression, and political repression, Greece transformed the demographic and ethnic composition of the region.

Between 1913 and 1928, Greece forcibly expelled thousands of Macedonians, primarily to Bulgaria. Under the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), Greece carried out a population exchange with Turkey, expelling 400,000 Muslims, including 40,000 Macedonian Muslims, and estimated 127,000 Macedonian Christians and simultaneously resettling 1.3 million Greek Orthodox refugees from Asia Minor in Aegean Macedonia. This massive population shift drastically altered the region’s demographics. The Greek government also redistributed land, granting property confiscated from Macedonians to Greek Orthodox refugees and colonists, further marginalizing the native population.

In a 1922 report of the Prefect of Florina, where the bulk of Macedonian-speakers resided, Karakasidou (2000) attests:

“It cannot be said that the situation with regard to national convictions (εθνικα φρονήματα) is pleasing. The population of the prefecture, by and large foreign-speaking (ξενόφωνος) and of another nation (αλοεθνής), of course is not delighted with any kind of improvement in our national matters. It is necessary for all officials, but particularly administrators, policemen and above all educators, to work systematically so that in due course the inhabitants’ national consciousness can be changed. Here, one cannot speak of distinctions along party lines but along national consciousnesses

[ … ]. Staff in schools should be the best available [and imbued] with national consciousness. Boarding schools and kindergartens should be established as well as night schools in which adults, male and female, learn the [Greek] language.”

The identity of Macedonians in Greece wasn’t just a natural expression of who they were—it was shaped and reshaped by politics and government influence. After Greece took control of Aegean Macedonia in 1913, the Greek government actively worked to redefine the identity of the local Macedonian population, promoting a Greek national identity while suppressing any recognition of their distinct ethnic roots.

The Greek state aggressively pursued policies of forced assimilation, denying the existence of a distinct Macedonian identity. The use of the Macedonian language was banned, even in private conversations. Although Greece briefly published a Macedonian-language primer, Abecedar, in 1925 to comply with international minority rights obligations, it was never introduced in schools, and all copies were destroyed. The state also implemented a campaign to erase Macedonian cultural heritage by renaming cities, villages, rivers, and mountains with Greek names. In 1927, all Macedonian inscriptions in churches and cemeteries were ordered to be replaced with Greek ones.

Oral Testimony – Jerry Karapalidis (Based on handwritten text on the first 3 of 7 pages of the letter originally written in Toronto on 21 October 2005. It recounts the lived experiences of a young Macedonian villager from Zelenich (Sklithro) during the turbulent years of the Metaxas dictatorship.

The mid‑1930s were marked by hardship across rural Macedonia. For families like the Karapalidis—eight children, limited resources, and scarce opportunities—life was already difficult. Ioannis Metaxas’ rise to power on 4 August 1936 intensified this hardship. His authoritarian regime enforced strict national homogenization policies, particularly targeting Macedonian‑speaking communities.

The size of the pressure was so big that many Macedonians from the villages of Western Macedonia left for the cities of Thessaloniki and Piraeus in search of jobs and better life. Whoever stayed in the villages suffered in every way imaginable from the government and officials and police agents.

If someone’s name and last name ended in -ov, -off, -ev, -eff they were immediately considered Slavo-Macedonian and therefore dangerous. If my name was Kara—palidov or Kara—palidoff and not Karapalidis I would have been thrown out or imprisoned. My father’s last name before was Karapalidov, but because of the pressure and fear he changed his name around 1914 to Karapalidis.

In Zelenich, the Macedonian language—spoken freely at home—became dangerous in public spaces. Teachers punished children for speaking their mother tongue, sometimes forcing them to kneel on stones or endure physical humiliation. Police kept lists of suspected “Slavophones,” and villagers lived under constant fear of surveillance. Despite the poverty, uncertainty, and political repression, youth found moments of beauty. Sundays were cherished: young men walked proudly through the village in their best clothing, passing the houses of young women who watched from their windows.

So, in 1936 when the dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas began the persecution against Macedonians of Greece intensified. If they caught people speaking Macedonian in the streets, shops, cafes, or in general at any time, the fines were big and the humiliations even greater. A typical fine for someone caught speaking Macedonian was 200 drachmas—an enormous amount for that era.

The village assemblies (Sobranya) that met for public matters were all forbidden. We Macedonians were forbidden from meeting even in our own homes. Such gatherings were considered illegal and dangerous (like Communists they said). Most of the customs of the village were strictly prohibited. Village dances and singing were forbidden. The women especially were warned not to sing Macedonian songs while washing the clothes near the river or in the yards. It was said that the king would punish them!

I clearly remember that the school in the village became a place where they would teach the Greek national anthem to the children and hold ceremonies with flags. The teacher had a wooden stick and whoever spoke Macedonian in the yard received punishment. Many times in the evenings when the officials entered the village, people ran to hide in the barns or vineyards. All of this happened before the war with Italy.

I lived through all of it and I write so the young will know what happened to us.

The first three pages of J. Karapalidis letter describe a period in which the Metaxas dictatorship intensified state repression against the Macedonian-speaking population of northern Greece. Through the author’s memories, we see how everyday life was transformed into a system of surveillance and coercion. Macedonian language use was punished with heavy fines, children were disciplined in schools for speaking it, and traditional gatherings, songs, and customs were banned. Families were pressured to change their surnames to Greek forms, erasing visible markers of Macedonian identity.

These experiences reflect a broader state project of forced assimilation, where Macedonians were treated as politically suspect and culturally foreign. The result was a climate of fear—villagers hiding from officials, teachers acting as enforcers, and the community living under constant threat. These pages show that long before World War II began, Macedonians were already enduring an organized campaign aimed at suppressing their language and identity.

The Greek government denied Macedonians any political representation and treated them as an unwanted minority. The Communist Party of Greece (KKE) was the only political force that recognized the existence and rights of Macedonians, but its influence was limited due to broader anti-communist repression. The authoritarian regime of General Ioannis Metaxas (1936–1941) intensified these policies, enforcing a complete ban on Macedonian cultural and linguistic expressions. Many Macedonians were imprisoned, tortured, or exiled to remote islands simply for identifying as Macedonian or speaking their native language.

The Greek government used policies and ideology to reshape Macedonian identity. Schools, the military, and the Orthodox Church played a big role in teaching Macedonians to see themselves as Greek, pushing a strictly Greek version of history while silencing Macedonian culture and language. Villages were renamed, people were forced to change their names to Greek ones, and speaking Macedonian was banned—all ways the state tried to erase their original identity.

The Greek government controlled how people expressed their identity by shaping the consequences of their choices. Those who accepted the Greek identity were given better social and economic opportunities, while those who held onto their Macedonian language and traditions faced discrimination, punishment, and even political persecution. Through both pressure and strategy, the state worked to gradually absorb Macedonians into the Greek national identity while pushing their own culture and heritage to the margins.

From 1924 to 1941, the Greek government implemented a range of policies aimed at assimilating the Macedonian population within Greece. Like any national identity, Macedonian identity was influenced by political, economic, social, and cultural forces, with the Greek government playing a major role. The state actively worked to erase and replace Macedonian identity through laws, education, and cultural policies, aiming to fully assimilate the Macedonian population into a Greek national identity.

Assimilation Policies

1. Population Exchanges and Resettlement

- 1923 Population Exchange: Approximately 1.5 million Orthodox Christian refugees from the Ottoman Empire (particularly Asia Minor, Pontus, and Eastern Thrace) were resettled in Greece. The Lausanne Treaty (1923) formalized this population exchange, primarily between Greece and Turkey, dramatically altering the ethnic composition of Macedonia.

- By resettling hundreds of thousands of refugees in these areas, the Greek government diluted the local non-Greek populations, reducing the numerical weight and political influence of Macedonian communities and strengthened the Greek cultural and demographic presence, reinforcing claims of the region as “Hellenic” and loyal to the Greek state.

- The confiscation and redistribution of Muslim properties (vacated due to the population exchange) disproportionately benefited refugees and Macedonian communities often lost access to lands or communal resources they had used for generations.

- The rapid influx of refugees generated competition for resources, increasing tensions and forcing local populations into subordination or assimilation.

- These refugees were granted land and privileges, and acted as cultural and political counterweights to the native Macedonian-speaking population .

- Public ceremonies and festivals celebrated Greek national heroes and narratives, excluding or erasing Macedonian cultural elements.

2. Linguistic Suppression

- The Macedonian language was officially banned. Speaking or teaching the language in public or private was prohibited, and offenders were fined or punished.

- Greek authorities replaced Macedonian place names with Greek ones, and individuals were required to adopt Greek-sounding names.

- Macedonian children were forbidden to speak their mother tongue in schools, and education was used as a tool to instill Greek national identity.

3. Cultural Suppression

- Macedonian cultural expressions, such as traditional songs, dances, and festivals, were discouraged or banned outright.

- Churches in the region were placed under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Church, which conducted services exclusively in Greek, marginalizing Slavic liturgical traditions.

- During 1925-1936, Macedonian-speakers faced intense assimilation efforts. Local politicians secured millions of drachmas for psychological and linguistic suppression. Florina Prefect Kalligas (1929) emphasized state intervention, even at the cost of other Greek regions. Assimilation relied on oppression, escalating to direct coercion.

- By 1932, the Prefect of Florina threatened the village of Buf for celebrating St. Nicholas’ feast by the old calendar, forcibly erasing a deeply rooted Macedonian tradition and exemplifying Greece’s escalating intolerance toward Macedonian identity.

- Cultural repression during this period laid the groundwork for later radicalization, contributing to the alignment of many Macedonians with communist and anti-monarchist forces during the Greek Civil War.

4. Repression and Surveillance

- Macedonians who resisted assimilation were subjected to persecution, including imprisonment, exile, or forced relocation.

- The Metaxas dictatorship (1936-1941) intensified these efforts, employing secret police to monitor and suppress any expressions of Macedonian identity.

- Public expressions of ethnic or cultural identity were often labelled as anti-Greek or subversive, leading to widespread fear and self-censorship.

5. Economic and Land Policies

- The redistribution of land to Greek settlers disadvantaged local Macedonian communities, many of whom lost their livelihoods.

- Macedonians were often excluded from economic opportunities, particularly in government employment, which required fluency in Greek and loyalty to the state.

6. Denial of Ethnic Identity through Nation-Building and Homogenization

- The Greek government viewed the Macedonian as a threat to national unity, particularly as Bulgaria and Yugoslavia had territorial claims over Macedonia.

- The government denied the existence of a distinct Macedonian ethnic identity, labelling Macedonian speakers as “Slavophone Greeks” and insisting they were Greeks who had been linguistically influenced by neighbouring Slavs.

- Census data and official records often categorized Macedonians as Greeks, erasing their ethnic identity.

Impact of Assimilation Policies

These measures, while successful in promoting Greek language and culture in the region, created lasting tensions and alienation among the Macedonian population. Many Macedonians were forced to conceal their ethnic identity, leading to a complex and unresolved legacy in the region.

Specific laws & Decrees

The Greek government implemented specific laws and decrees from 1924 to 1941 to force the assimilation of the Macedonian population. These legal measures were key tools in suppressing Macedonian identity and promoting a homogenized Greek national identity in the region. Some of the most notable include:

1. Language Suppression

Law 3348/1925 – Banned the public use of the Macedonian language.

- Νόμος 3348/1925 – Απαγόρευση Δημόσιας Χρήσης Ξένων Γλωσσών Ο νόμος αυτός απαγόρευε τη χρήση της σλαβικής (μακεδονικής) γλώσσας σε δημόσιους χώρους, σχολεία, καταστήματα και διοικητικές υπηρεσίες. «Απαγορεύεται η χρήσις ξενικών διαλέκτων εις δημόσιους χώρους, καταστημάτων, σχολείων και διοικητικών υπηρεσιών.» — ΦΕΚ Α’ 298/1925

Law 2366 of 1930: Prohibited the use of “non-Greek” languages in public and private life. It was aimed at eradicating the Macedonian language from schools, churches, and everyday communication. The Circular of the Ministry of Education specifically instructed schools in the Florina region to eradicate the use of the Macedonian language among students. Teachers were ordered to report any students speaking Macedonian, with punishments ranging from fines for parents to physical punishments for children.

Decree of 1936 (Metaxas regime): Instituted stricter enforcement of the ban on the Macedonian language. Individuals caught speaking Macedonian could face fines, imprisonment, or public humiliation. Children in schools were specifically targeted, with penalties for speaking Macedonian even during recess. The Metaxas regime placed special focus on Florina as a “hotbed of Slavophone activity.” Local authorities were given explicit orders to monitor and suppress the use of Macedonian in public spaces and households.

2. Renaming of Places and People

Law 4096 of 1929: Authorized the renaming of towns, villages, and geographical features with Slavic or Turkish names into Greek ones. For example, Solun became Thessaloniki, Voden became Edessa and Zelenich became Sklithro.

Law 4322 of 1932: Mandated the Hellenization of personal names. Macedonians were pressured to adopt Greek-sounding names for themselves and their children, and official documents were altered to reflect these changes. Local authorities in Florina implemented a campaign to forcibly change Macedonian personal names to Greek ones. Birth certificates, marriage records, and other legal documents were altered to reflect Greek-sounding names. Families were often threatened with fines or denial of public services if they resisted.

804 Macedonian Village Name Changes (Click on Title to view the whole List)

This document presents a detailed record of 804 Macedonian villages in Aegean Macedonia, a region annexed by Greece in 1912, whose names were systematically altered between 1926 and the early 1940s as part of a broader policy of forced Hellenization. Compiled by Lena Jankovski and Alex Bakratcheff, the list captures a key aspect of cultural erasure following the 1913 Treaty of Bucharest, when Greece undertook a national campaign to replace all non-Greek toponyms—including Slavic, Turkish, and Albanian place names—with Greek ones. This process extended beyond geography, encompassing the forced Hellenization of personal names and the suppression of the Macedonian language, particularly during the Metaxas dictatorship (1936–1941). A 1927 legislative decree even claimed that “there are not any non-Greek people in Greece,” signaling the state’s intent to eliminate visible traces of Macedonia’s multiethnic past through linguistic and cultural assimilation.

3. Restrictions on Religious Practices

1924 Protocol for the Greek Orthodox Church: Required all church services to be conducted in Greek. Churches that had previously used Old Church Slavonic or Macedonian for liturgies were forced to comply, alienating many Macedonian speakers. Churches in Florina that had previously used Old Church Slavonic or Macedonian for liturgical purposes were forced to switch to Greek. Priests who resisted were dismissed or replaced with Greek-speaking clergy

1926 Decree on Ecclesiastical Uniformity: Gave Greek Orthodox bishops authority to suppress any religious practices deemed “non-Greek” in character, further marginalizing Macedonian religious traditions.

Religious Monitoring (1930s): Special attention was given to suppressing religious practices tied to Slavic traditions, which were labelled as “unorthodox” or “subversive.”

4. Censorship and Cultural Repression

Law 4229/1929 – Criminalized anti-national behaviour and was applied against Macedonian cultural expression.

- Νόμος 4229/1929 – Αντικομμουνιστικός Νόμος “Ιδιώνυμο” Αν και θεσπίστηκε για την καταστολή του κομμουνισμού, ο νόμος αυτός χρησιμοποιήθηκε για τη φίμωση των πολιτιστικών εκφράσεων των Μακεδόνων. «Περί μέτρων καταστολής του κομμουνισμού και άλλων αντιθέτων προς το καθεστώς ενεργειών.» — ΦΕΚ Α’ 317/1929

Press Censorship Law of 1936: Prohibited publications in any language other than Greek. Macedonian-language books, newspapers, and pamphlets were confiscated and burned.

Order of the Ministry of the Interior (1937): Outlawed traditional Macedonian songs, dances, and folklore, replacing them with Greek cultural elements in public events and celebrations.

Law 509/1937 – Used extensively during the Metaxas regime to dissolve minority organizations and imprison dissidents.

- Νόμος 509/1937 – Προστασία Καθεστώτος και Διάλυση Οργανώσεων Κατά τη διάρκεια της δικτατορίας του Μεταξά, αυτός ο νόμος χρησιμοποιήθηκε για τη διάλυση μειονοτικών οργανώσεων και τη φυλάκιση ακτιβιστών. «Περί προστασίας του κοινωνικού καθεστώτος και της ασφαλείας του κράτους.» — ΦΕΚ Α’ 316/1937

5. Land and Property Policies

1924 Refugee Settlement Law: The government resettled large numbers of Pontic Greeks and other Greek refugees from Asia Minor into Florina.

Law 1078 of 1926 (Agrarian Reform Law): Redistributed land owned by Macedonian families to incoming Greek refugees as part of a broader effort to change the demographic balance in Macedonia.

Settlement Commission of 1927: Focused on placing Greek-speaking settlers in formerly Slavic-majority villages, pushing Macedonians to peripheral or less fertile lands.

By 1928, it was estimated that over 40% of Florina’s population consisted of newly settled Greek refugees. These settlers were encouraged to act as agents of Hellenization, often receiving preferential treatment in terms of land redistribution and economic opportunities.

Settlement Commission for Florina (1927): This body was tasked with accelerating the demographic transformation of Florina by redistributing lands from Macedonian families to Greek refugees.

6. Surveillance and Policing

Law 4229 of 1929 (“Idionymon”): Targeted “subversive activities,” which included promoting Macedonian identity or using the Macedonian language. This law was used to arrest and exile individuals accused of anti-Greek sentiment. The Idionym law, which criminalized activities deemed subversive to the state, was heavily enforced in Florina. Any promotion of Macedonian identity—through cultural events, religious practices, or even informal gatherings—was met with arrests and deportations. Florina was heavily patrolled by the Greek Gendarmerie and secret police, who maintained detailed records on local families suspected of harboring “anti-Greek” sentiments.

Decree of 1936: Under the Metaxas dictatorship, the secret police monitored and repressed Macedonian cultural expressions. Macedonians who resisted assimilation were imprisoned or exiled to remote islands like Gyaros and Makronisos.

7. Education Policies

Law 1297 of 1936: Required all instruction in schools to be conducted exclusively in Greek. Teachers who used any other language could be dismissed or prosecuted.

- Εκπαιδευτικές Διατάξεις – Διάταγμα 1936–1939 Οι εντολές του Υπουργείου Παιδείας υπό τον Μεταξά απαγόρευαν ρητά τη χρήση σλαβικών γλωσσών στην εκπαίδευση. «Απαγορεύεται αυστηρώς η διδασκαλία και η χρήσις της σλαβικής γλώσσης εις τα σχολεία του Κράτους.» — Υπουργική εγκύκλιος, 1937–1939

Ministry of Education Circular of 1937: Prohibited Macedonian children from speaking their language even during breaks or outside school, with punishments including corporal punishment and expulsion.

Impact of These Laws

These laws and decrees systematically sought to eliminate Macedonian identity through cultural, linguistic, and economic pressures. They not only targeted public expressions of Macedonian heritage but also intruded into private life, creating an environment of fear and repression. The long-term consequences included the forced assimilation of many Macedonians, significant cultural loss, and enduring ethnic tensions.

The Greek government implemented specific measures targeting the Florina region, which had a significant population of Macedonians. Florina was seen as a key region for assimilation policies due to its proximity to the Yugoslav border and its ethnolinguistic diversity. While many of the national laws and decrees applied uniformly across Macedonia, some actions were tailored specifically for Florina to address its distinct demographic and cultural landscape.

Officials automatically labelled anyone who spoke Macedonian as Bulgarian, viewing them with suspicion. Since nearly all villagers spoke Macedonian, they were collectively branded as Bulgarians and treated with distrust. Most soldiers and police officers were wary of the Macedonian-speaking population, keeping them under close watch—especially those with relatives in America, where Macedonian nationalist movements were gaining traction (Mandatzis 1997).

Florina became one of the most repressed regions in Northern Greece due to these assimilation policies. The region’s proximity to Yugoslavia heightened Greek fears of secessionist movements, prompting harsher enforcement of these laws compared to other areas. This led to widespread resentment and alienation among the local population, many of whom were forced to suppress their ethnic and cultural identity to avoid persecution.

The Metaxas Dictatorship and Forced Hellenization

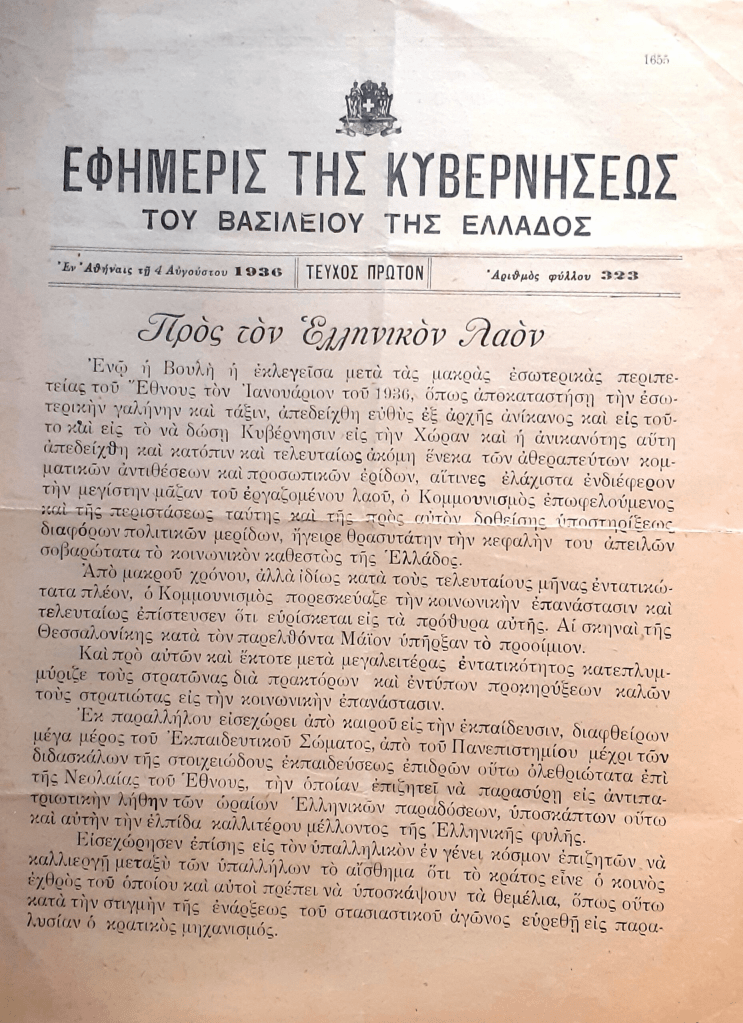

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE KINGDOM OF GREECE

In Athens, August 4, 1936

Issue One — Sheet Number 323

English Translation of the above:

To the Greek People

While the Parliament elected after the long internal trials of the Nation in January 1936, in an effort to restore internal peace and order, had immediately proven incapable of governing, and this incapacity culminated in chaos and, most recently, in an incredible clash of party oppositions and personal ambitions, causes of deep concern to the vast majority of the working people, Communism, exploiting the prevailing anarchy and using all the methods of its usual propaganda, fearfully raised its head and threatened the social order of Greece.

For a long time, but especially in recent months, Communism has intensified its efforts toward social revolution and, in May, manifested itself dangerously in Thessaloniki. The signs of this unrest and the increasing intensity of social agitation, accompanied by frequent demonstrations of zeal from its followers, are turning toward social revolution.

It has also been systematically infiltrating education for some time, from the university to the schools of secondary education, corrupting the Youth of the Nation, whom it seeks to detach from the noble traditions of the Greek People, thus undermining all hope of a better future for the Greek race.

It has also infiltrated the public service, seeking to instill in officials the belief that the state is not the common good of all and must not be supported as a foundation, thus at the moment of engagement in the national struggle, paralyzing patriotic enthusiasm.

The above proclamation effectively sets the ideological justification for the establishment of Ioannis Metaxas’ authoritarian regime. It accuses communism of destabilizing Greek society and infiltrating education and public services — themes that were commonly used to suppress not only leftist elements but also ethnic minorities, including Macedonians, through censorship, surveillance, educational reform, and forced Hellenization.

During the 4th of August Regime, Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas intensified efforts to ‘purify’ Greek national identity. Special security units raided villages, burned Slavic books, renamed settlements, and arrested Macedonian teachers. Children were punished for speaking Macedonian in schools, and traditional customs were officially discouraged or banned.

During the 1930s, several reports and scholarly analyses documented systemic persecution of the Macedonian-speaking minority in Greece. These accounts highlight the Greek state’s efforts to suppress Macedonian cultural and linguistic identity.

One notable source is the work of historian Iakovos D. Michailidis, who discusses the demographic changes and assimilation policies in Greek Macedonia during this period. His research indicates that the Greek government implemented strategies to alter the population’s ethnic composition and promote a homogeneous national identity.

It’s paradoxical that while the Greek state refused to recognize Macedonians as a national minority and only acknowledged them as a linguistic group, it simultaneously prohibited them from using their distinct language.“

The Greek state’s refusal to recognize the Macedonian population as a national minority, while at the same time implementing harsh policies to suppress their distinct language and culture, demonstrates the contradictory nature of assimilationist nation-building strategies.

On the one hand, by categorizing Macedonians merely as a linguistic group (the so-called “Slavophones”), the Greek state could deny them any political or national rights that come with recognition as a national minority. This legally erased the Macedonian identity from public discourse and governance.

On the other hand, the suppression of the Macedonian language, including banning its public use, changing names of people and places, and enforcing Greek language education, clearly indicates that the state saw the Macedonian language as a threat to its nationalist project—so much so that it had to be eradicated.

Zelenich to Sklithro

The village of Sklithro, formerly known as Zelenich, located in the Florina region, experienced specific assimilation policies between 1924 and 1941. These measures were part of broader national efforts to enforce a homogeneous Greek identity, particularly in areas with significant Slavic-speaking populations.

1. Renaming of the Village

Official Name Change (1927): In line with the Greek government’s policy to Hellenize place names, the village’s name was changed from “Zelenich” to “Sklithro” in 1927. This renaming aimed to erase Slavic toponyms and reinforce Greek national identity.

- Διατάγματα Ελληνοποίησης Τοπωνυμίων (1926–1939) Διοικητικά διατάγματα που μετονόμασαν χωριά και πόλεις από σλαβικά, τουρκικά ή αλβανικά ονόματα σε ελληνικά. Παράδειγμα: «Το όνομα Ζέλενιτσα μεταβάλλεται εις Σκλήθρον.» — Εφημερίς της Κυβερνήσεως (1926–1939)

2. Language Suppression

Prohibition of the Macedonian Language: Residents of Sklithro, like those in other parts of Florina, faced restrictions on using the Macedonian language. Speaking Macedonian in public spaces, schools, and even within households was discouraged or banned, with authorities enforcing these measures to promote the exclusive use of Greek.

- Katina XOX, as a young student in grade 3, witnessed a teacher viciously whipping a classmate with a stick simply for speaking a word in Macedonian. The trauma of that moment silenced her completely in her mother tongue—she never spoke it again. Later in life, she married a man whose parents were Anatolian refugees who had settled in the village. He forbade her from speaking Macedonian, referring to it as a “dirty language.”

- Magda XOX was celebrating “Lazaritsa,” a traditional ritual where young girls went from house to house during Lazarus Saturday, singing songs. The girls were so excited by the custom that they began singing in Macedonian. The next day at school, the Greek teacher discovered what had happened and punished all the girls by withholding their daily nutritious treats and drinks. The teacher also warned them of severe consequences if they continued to speak or sing in “Bulgarian.” Macedonian was not recognized as a language and was deliberately referred to as “Bulgarian” to deny its existence and to fully eradicate its use.

Many government officials arriving in the region were frustrated to find that a large number of villagers did not speak Greek. For many, being assigned to “this corner of Greece” felt like an undesirable post, leading to hostility toward the Macedonian-speaking minority. Numerous reports from Greek military and police officers, teachers, and other officials at the time criticized the government’s approach—or lack thereof—toward the region. Most called for stronger efforts to assimilate the Macedonian-speaking population.

3. Settlement of Greek Refugees

Population Resettlement: Following the population exchanges and resettlements in the 1920s, Greek refugees from Asia Minor were settled in various parts of Macedonia, including the Florina region. While specific data for Zelenich-Sklithro is limited, it’s likely that such settlements impacted the village’s demographic composition, aligning with national strategies to alter the ethnic landscape. An example is Sklithro is depicted in the newspaper Elenchos of Florina, which stated on 18 January 1929:

Click here to read more on the exchange and those who settled in Sklithro-Zelenich.

4. Cultural and Religious Changes

Hellenization of Religious Practices: Church services in Zelenich were mandated to be conducted exclusively in Greek, replacing the previous use of Church Slavonic or Macedonian. This policy was designed to integrate religious practices into the broader framework of Greek national identity. Following the settlement of Anatolian Orthodox refugees, non-Greek clergy were never again permitted to serve in the village.

5. Economic and Social Pressures

Land Redistribution: The government’s land redistribution policies favoured Greek refugees and settlers, potentially disadvantaging local Macedonian populations in villages like Sklithro. This economic pressure was a tactic to encourage assimilation or migration.

- In Sklithro a farmer, when presented to the Commission which was to decide on his disputed land, was so stressed that, instead of showing the contracts he had, he showed the Commission something like a lease. The committee took his fields from him. …(Fotiadis 2004, 254)

6. Surveillance and Policing

Monitoring of Local Populations: Authorities closely monitored villages in the Florina region, including Sklithro, for any expressions of Macedonian identity. Individuals resisting assimilation faced penalties, creating an atmosphere of fear and repression. Use actual police officer names who spied on people and were encouraged to marry local women to displace native traditions

These policies led to significant cultural and demographic shifts in Sklithro-Zelenich, contributing to the broader national objective of homogenizing the population. The long-term effects included the suppression of Macedonian cultural expressions and a transformation of the village’s identity.

An example of the Greek policy towards Macedonians especially in Zelenich, is a story by Suzanne Brazeau of her mother Vassilka Shikleff, daughter of Magda and Ristos Shikleffand. Vassilka learned to speak and write Greek in the village school. It was forbidden to speak Macedonian. In fact, her father went to prison for two years for speaking Macedonian to his donkey. His defence, “Your Honour, my donkey doesn’t understand Greek.”

Summary of the Interwar Years (1924-1941) on Macedonians in Greece

- Assimilationist Policies:

- The Greek state implemented a forceful assimilation campaign targeting the Macedonian population of Northern Greece, especially in Aegean Macedonia, after the 1923 population exchange.

- Policies included the banning of the Macedonian language, forced name changes, and state-sponsored education in Greek, deliberately erasing local Macedonian identities .

- Nation-Building and Homogenization:

- The Greek government viewed the Macedonians as a threat to national unity, particularly as Bulgaria and Yugoslavia had territorial claims over Macedonia.

- Efforts were made to redefine these communities as “Slavophone Greeks”, rather than allowing space for a distinct ethnic identity .

- Impact of Refugee Settlement:

- The settlement of Greek Orthodox refugees from Asia Minor (following the Greco-Turkish War and population exchange) was used as a strategic tool to alter the demographic balance in Macedonia.

- These refugees were granted land and privileges, and acted as cultural and political counterweights to the native Macedonian-speaking population .

- Suppression of Cultural Expression:

- Cultural repression during this period laid the groundwork for later radicalization, contributing to the alignment of many Macedonians with communist and anti-monarchist forces during the Greek Civil War.

| Policy Type | Enforced Under | Purpose | Impact on Macedonians |

| Language bans | 1920s–Metaxas era | Eliminate Macedonian public expression | Criminalized native language use |

| Name changes | 1926-1938 | Hellenize personal and place identity | Erased visible signs of Macedonian culture |

| School reforms | 1920s-1941 | Indoctrinate Greek identity | Prevented transmission of native culture |

| School reforms | Metaxas regime | Suppress “non-Greek” customs | Repressed religious and social expression |

In summary, the Greek government and society expropriated the consciousness of Macedonians in Greece during the interwar years of 1924-1941 and it continues to this day.

The expropriation of Macedonian consciousness in Greece refers to the historical and ongoing processes through which the Greek state and society have suppressed, assimilated, or denied the distinct ethnic and cultural identity of the Macedonian minority in Greece. This has taken various forms, including political, legal, educational, and social mechanisms designed to enforce a singular Greek national identity.

Fragments of Resistance: The Macedonian Fight for Identity under Greek Rule

Macedonians Organize for Liberation – Eksi-Su, 1934

In October 1934, in the village of Eksi-Su, several groups of determined Macedonians came together to organize the struggle for our people’s liberation. Two groups of nine members each, along with a third of six members, took up the task of enlightening the local peasantry and mobilizing resistance.

They extended an open call to the neighboring villages of Ajtos, Zeleniche, and Ljubetino, urging them to form their own groups and join the movement. “Together, we envision the creation of a Macedonian newspaper—published in our own language—to amplify our voices and assert our identity.”

“With unwavering conviction, we declare to our Greek rulers: We are not Greeks, nor are we Bulgarians or Serbs. We are pure Macedonians. Our history stands behind us, marked by relentless struggle for the freedom of Macedonia, and we will continue this fight until liberation is achieved.” Eksi-Su, December 26, 1934 — Many Macedonian Fighters (Rizospastis, 24-351, 1. XI 1934, p. 3)

This statement, first published in the leftist newspaper Rizospastis in 1934, reflects the grassroots efforts of Macedonian villagers to resist assimilation policies imposed by the Greek government. It highlights both the organizational spirit of local communities and their determination to preserve and assert their distinct Macedonian identity, even amid intense political repression and cultural erasure during the interwar years.

More “Letters to Rizospastis (Greek Communist Party Publication)” can be found by clicking on this title.

Ta Mystika Tou Valtou (1937) – Penelopi Delta’s

Recognition of Macedonians

During the interwar years, long before the Metaxas dictatorship formalized its project of national homogenization, the lived reality in Western Macedonia was already marked by deep cultural tension. Even in the realm of Greek national literature, the existence of a Macedonian-speaking population in the region could not be concealed. Penelope Delta’s Sta Mystika tou Valtou (1937) stands as a revealing case. Although written as a patriotic Greek novel intended to inspire national sentiment among young readers, Delta’s narrative inadvertently preserves a detailed ethnographic snapshot of the Macedonian population living throughout the Florina–Kastoria basin. As Peter Mackridge demonstrates, Delta explicitly acknowledges the presence of a local Slavic (Macedonian) language, spoken fluently alongside Greek and sometimes Turkish, and she constructs her story around the multilingual, multiethnic reality of the region (Mackridge, 2009). Characters traverse landscapes known best through Macedonian toponyms, communicate in a mixed linguistic world, and navigate identities that cannot be reduced to the rigid categories promoted by the Greek state.

Moreover, Delta’s attempt to reinterpret Macedonian Slavs as “lost Greeks” underscores the very distinctiveness she hoped to dissolve. In her novel, the (Macedonian) Slavic-speaking inhabitants appear as a separate community that has supposedly been “dragged” between Greek and Bulgarian national projects—an admission that a distinct Macedonian population existed outside both identities. Her insistence on their “re-Hellenization” reflects a broader interwar ideology: that the state could reshape identity through schooling, language suppression, and cultural pressure. The rhetorical need to “bring them back” to Greekness presupposes that they did not already belong to it. This aligns closely with interwar policies in villages like Zeleniche/Sklithro, where linguistic bans, school surveillance, and forced public conformity sought to erase the everyday Macedonian language spoken in homes and fields. Delta’s fiction becomes a parallel source and in some ways a corroborating one to the oral testimonies from the region: a Greek nationalist writer who nonetheless records the multilingualism, toponyms, and customs that betray the presence of a Macedonian-speaking population.

Delta’s novel therefore serves as a bridge between literary representation and lived experience. While written for ideological aims, it unintentionally documents the same social reality described by villagers in Zeleniche, Aetos, and across Western Macedonia: a population whose language, songs, and identity persisted despite pressure from authorities and rival nationalist groups. Within the broader interwar story marked by population exchanges, refugee settlement, and intensifying Greek state control, Delta’s portrayal reinforces the undeniable fact that Macedonian communities existed as a distinct, internally coherent group. And as Macedonians entered the 1930s and early 1940s, this distinctiveness would only heighten state anxiety, contributing directly to the repression that characterized the Metaxas regime and shaping the hardships that would later intensify under Axis occupation.

Sources:

Alvanos, R. (2019): Parliamentary politics as an integration mechanism: The Slavic-speaking inhabitants of interwar (1922–1940) Western Greek Macedonia, History and Anthropology, DOI: 10.1080/02757206.2019.1639051. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334683508_Parliamentary_politics_as_an_integration_mechanism_The_Slavic-speaking_inhabitants_of_interwar_1922-1940_Western_Greek_Macedonia

Alvanos, R. (2005). Κοινωνικές συγκρούσεις και πολιτικές συμπεριφορές στην περιοχή της Καστοριάς (1922–1949) [Doctoral dissertation, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki]. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343514454_Raumondos_Albanos_Koinonikes_synkrouseis_kai_politikes_symperiphores_sten_perioche_tes_Kastorias_1922-1949_didaktorike_diatribe_APTH_2005

Artemi, E. (2013, January 21). Η περίοδος του Μεσοπολέμου και οι κρίσεις στην Ελληνική Κοινωνία (The Interwar Period and the Crises in Greek Society). Academia.edu – Find Research Papers, Topics, Researchers. Book Link: Academia.edu

Blanchet, J. (1918). Traditional dance “oro”, village Negochani (Niki) [Photograph]. Macedonia1912-1918.blogspot.com. https://macedonia1912-1918.blogspot.com/2017/02/negochani-village-niki-during-ww1.html

Boeschoten, R. V. (1991). From Armatolik to people’s rule: Investigation into the collective memory of rural Greece, 1750-1949.

Brazeau, S. (2022, June 30). Suzanne Brazeau’s story of Vassilka. My Mother’s Story. https://mymothersstory.org/2015/04/16/suzanne-brazeaus-story-of-vassilka/

Clark, B. (2006). Twice a stranger. Google Books. https://books.google.ca/books?id=kVZ3sLBEPEcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

Danforth, L. (1995). The Macedonian conflict. Google Books. https://books.google.ca/books?id=ZmesOn_HhfEC&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

Danforth, L. M. (2010, March 19). The Macedonian minority of northern Greece. Cultural Survival. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/macedonian-minority-northern-greece?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Denying ethnic identity. (1994, March 31). Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/1994/04/01/denying-ethnic-identity/macedonians-greece?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Elaliberta.gr. (2018, February 2). Η άλλη όψη του Μακεδονικού Αγώνα (The other side of the Macedonian Struggle). Αρχική – elaliberta.gr. (From the book: Tasos Kostopoulos, Leonidas Embirikos, Dimitris Lithoksou, Greek Nationalism – Macedonian Question. The Ideological Use of History. A Discussion in Philosophy, Left Movement of History and Archaeology, Athens 1992 (2nd edition). Source: lithoksou.net) Article Link

ΓΙΩΤΑ, M. (2005). Η πολιτική ένταξη των προσφύγων του 1922 στην Ελλάδα του μεσοπολέμου: 1922-1940 – Κωδικός: 19839 (The political integratio of the refugees of 1922 in interwar Greece: 1922-1940). https://www.didaktorika.gr. https://thesis.ekt.gr/thesisBookReader/id/19839?lang=el#page/1/mode/2up

Gounaris V. K. (1994). The Slavonic speakers of Macedonia: the course of integration into the Greek national state, 1870-1940. Macedonian, 29(1), 209–237. Article Link

Goumenos, Thomas and Goumenos, Thomas, Greek Perception of the Balkans: Edgy Coexistence or Difficult Relationship? (August 18, 2005). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2345424 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2345424

Greek General State Archives (GAK). (1927–1928). School inspection reports for the Florina region (Sorovits, Rudnik, Prekopana, etc.). Athens: Greek Ministry of Education.

Herzfeld, M. (1982). Ours once more. Google Books. https://books.google.ca/books?id=Vh-4DwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

Revised 2020

Horncastle, J. R. (2016, December 7). The Pawn that would be King: Macedonian Slavs in the Greek Civil War, 1946-49. Summit Research Repository. https://summit.sfu.ca/_flysystem/fedora/sfu_migrate/16972/etd9955_JHorncastle.pdf

Ilieva, J., & Covev, B. (2015, August). The process of ethnic homogenization of the Greek nation and its impact over the denouncing of the cultural identity of the other ethnic groups: The case with the Macedonian ethnic minority. Academia.edu – Find Research Papers, Topics, Researchers. Article Link

Jankovski, L., & Bakratcheff, A. (n.d.). Macedonian village names: The names of 804 Macedonian villages in Aegean Macedonia occupied by Greece in 1912, that have forcibly been changed from 1926 and forward. Idoc.pub. https://idoc.pub/documents/macedonian-village-names-qn85eer8z1n1

Karakasidou, A. N. (2009). Fields of wheat, hills of blood: Passages to nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990. University of Chicago Press. https://archive.org/details/fieldsofwheathil00kara

Karapalidis, J. (2005, October 21). Memoirs of a Macedonian Villager, 1936–1947 – Letter describing experiences in Sklithro–Zelenich. CMHS Oral History Archive.

Kitromilides, P. M. (2013). Enlightenment and revolution. Google Books. https://books.google.ca/books?id=oTCwAQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

ΚΩΣΤΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ, ΤΑΣΟΣ. (2008 Η απαγορευμένη γλώσσα. Κρατική κατα στολή των σλαβικών διαλέκτων στην ελληνική Μακεδονία, Μαύρη Λίστα, Αθήνα (The Forbidden Language: State Suppression of Slavic Dialects in Greek Macedonia) Book Link

Kostopoulois, T. (2009, January 1). Το Μακεδονικό στη δεκαετία του ’40 (The Macedonian in the 1940s). Academia.edu – Find Research Papers, Topics, Researchers. Book Link

Kostopoulos, T. (2011). How the North was won: Ethnic cleansing, population exchange and colonization policy in Greek Macedonia. European Journal of Turkish Studies, 12. https://journals.openedition.org/ejts/4437

Koutsopoulou, K. (2019). Ο ελληνικός Εμφύλιος και η μετεμφυλιακή πραγματικότητα στην πεζογραφία της υπερορίας (1950-1955) (The Greek Civil War and the post-civil war reality in the prose of the overseas region (1950-1955). Academia.edu – Research Paper. LINK

Mackridge, P., & Giannakakē, H. (1997). Ourselves and others : The development of a Greek Macedonian cultural identity since 1912 : Free download, borrow, and streaming : Internet archive. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/ourselvesothersd0000unse

Mackridge, P. (2009). Macedonia and Macedonians in Sta Mystika Tou Valtou (1937) by P. S. Delta. Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 27(1), 1–15. https://pasithee.library.upatras.gr/dialogos/article/view/5209/4953

Michailidis, I. D. (2009, September 26). The Statistical Battle for the Population of Greek Macedonia. Macedonian Heritage: An online Review of the Affairs, History and Culture of Macedonia. https://www.macedonian-heritage.gr/HistoryOfMacedonia/Downloads/History%20Of%20Macedonia_EN-12.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Michailidis, I. D. (2015). On the other side of the river:. Macedonia, 68-84. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt18fsbkm.11

Mylonas H. Methodological Appendix. In: The Politics of Nation-Building: Making Co-Nationals, Refugees, and Minorities. Problems of International Politics. Cambridge University Press. Book Link

Poulton, H. (1995). Who are the Macedonians? : Hugh Poulton : Free download, borrow, and streaming : Internet archive. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/whoaremacedonian00poul

Poulton, H. (2018, September). Macedonians in Greece. Minority Rights Group. https://minorityrights.org/communities/macedonians-3/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Updated September 2018

Rossos, A. (2013). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A history. Hoover Institution Press.

Roudometoff, V. (2002). Collective memory, national identity, and ethnic conflict. Google Books. Book Link

Sfetas, S. (2002). Ourselves and others: The development of Greek Macedonian cultural identity since 1912 (Review of the book edited by P. Mackridge & E. Yannakakis). Makedonika, 33(1), 345–350. https://doi.org/10.12681/makedonika.293

Sfetas, S. (2018, July 11). Η Γένεση του «Μακεδονισμού» στον Μεσοπόλεμο. Ερανιστής. (The Genesis of Macedonianism in the Interwar Period) Book Link