The Mürzsteg Agreement, signed on October 2 1903, Macedonia was being policed by an International Commission constituted of French, Italian, British, Russian and Austrian troops. A joint memorandum of Russia and the Austro-Hungarian Empire transmitted to the Ottoman Empire, proposed a series of political reforms in the vilayets of Thessaloniki, Kosovo and Monastir. The purpose of these reforms was to maintain the integrity of the Ottoman state, threatened by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) and at the same time procure greater rights for Christians living under it. The Ottoman Empire agreed to the proposed reforms on 24 November.

But, from the failed 1903 Macedonian Ilinden Uprising right up to 1908 the situation in Macedonia was effectively one of civil war on all fronts with not only armed guerrilla bands, but also, civilians against each other. The violence was supported by the governments of Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. The Young Turk movement forced the Ottoman authorities in 1908 to attempt to end the anarchy in Macedonia, and their promise of equal civil rights did not persuade the Christians to stop slaughtering each other.

According to the report of the Englishman Harry Lamb, in the first 4 months of 1908, a total of 1080 political murders were carried out in Macedonia of which there were, 649 Bulgarians, 185 Greeks, 39 Serbs, 36 Vlahs, 130 Muslims and 40 soldiers. The interesting fact in this report is that the identity of all those killed was determined according to the individuals religious alliance and not their ethnicity. Even in death, ethnic Macedonians were misidentified as Bulgarians, Greeks and Serbs. Those identified as Bulgarians were Macedonians who belonged to the Bulgarian Exarchist church and Macedonians who were aligned with the Greek Patriarchist church were called Greek.

This period did not only include violence committed by military or paramilitary groups but also civilians against civilians. Even family-members turned against each other when they decided to adhere to a different religious identity. The influence of national ideas was so strong, that personal decisions were able to destroy traditional family structures and this exposed converted villages to violence. Kidnapping, ransom, mass-theft of animals, blackmailing, threatening letters, the unconcern of Ottoman authorities and bribery became the norm in Western Macedonia.

Fathers who had fought in the 1903 uprising and came out of jail, when they approached the Bulgarian agents for support and were denied, they were then assisted by the Greek/Serbian agents and paid to spy on their own people. They were also promised to have their sons excepted into the Greek/Serbia/Bulgarian school systems. On one such occasion the son refused to go to Greek school to become a teacher and approached the Bulgarians who sent him to ‘Teachers’ Training College in Kjustendil. Thus began the father – son battle.

As a result, some villagers thought, that time had come to profit from their national identity beyond the many inconveniences it had caused to their families and fellow villagers. Those Macedonian revolutionaries who were loyal to the cause of an independent Macedonia were betrayed by those who sold their faith and souls to Bulgarians, Greeks and Serbs who would give them a new national identity. In doing so, the Greeks, Serbians and Bulgarians used these new converts (Macedonians) to secure their own claims on Macedonia by adding these people on their own statistical ledgers.

Under the Mürzsteg Agreement, Russia and Austria-Hungary had been commissioned by the Imperial powers to stop all this violence and to improve conditions of the Christians in the Balkans but their actions were regarded destructive and only promoted their self interests in the region and the protection of the Ottoman Empire. The disturbances in Macedonia had brought together large numbers of Turkish troops, and these common soldiers were unpaid and wasting their time. The officers were unable to preserve order and dissatisfied with the presence of the foreign officers, who were a constant reminder that the days of the Empire were numbered. Seeing that their control of the Empire was dwindling, young intellectuals devised a plan to overthrow the Sultan and save the empire from further losses.

Young Turk Revolution 1908

On July 24, 1908, the bloodless revolution by which the rule of Abdul Hamid was overturned and the Young Turk regime established in the Ottoman Empire. The belief of the Young Turks that a regeneration of the Empire was necessary to prevent the inevitable and irretrievable loss of European Turkey precipitated the revolution of 1908, and the paramount plank in the program of regeneration was the solution of the Macedonian problem. The policy which the Young Turk adopted to solve the Macedonian problem was to strengthen the Muslim element.

No sooner had the revolution taken place the new regime had to deal with a number of setbacks for the empire. In that same year (1908); on October 5 Prince Ferdinand proclaimed the independence of Bulgaria; on October 6 the Emperor Francis Joseph announced the formal annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the Hapsburg dominions; and on October 12 the Cretan Assembly voted the union of the island of Crete with the Kingdom of Greece.

After the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina by Austria-Hungary the Young Turks sent agents into those countries to induce the Muslim population to emigrate to Macedonia. These immigrants were settled by the Government in those districts where the Muslim population was weak. This created an element of people who were ignorant, unruly, fanatical and forced to emigrate. As a result, the presence of this lawless, malcontent element in Macedonia brought more violence and ended in an irretrievable disaster for Turkey.

Military Service

The second policy adopted by the Young Turks to secure the loyalty of their Christian subjects in European Turkey was the abolition of the Karadj or head tax, by which Christians were exempted from military service, and the enrolling of them in the army. This policy was attractive in theory but impracticable in application. The social, educational, temperamental, and religious incompatibility of Muslims and Christians, commanded exclusively by Muslims was not possible. This system of obligatory military service was used from its inception as a means of extortion and terrorism; Jews and Christians who were financially able were forced to pay the £40 prescribed for exemption, and those who were unable to pay were practically reduced to military servitude. Under these conditions the Christian elements preferred exile, and between 1909 and 1914 Turkey lost hundreds of thousands of its best subjects by emigration.

On one such occasion, Kiril (Karl) Nićev having migrated from Zelenich to Istanbul, left his business, a milk and cheese factory due to being conscripted into the Turkish army. According to oral history, he had married Dotska (Dorathy) Miskova from the same village and had two kids, Paraska and Blagoj (Goetso). Since the military policy dictated that if an able bodied Christian had a son, they were required to join the army. Blagoj was only 3 years old when the policy came into effect, and his existence was kept a secret but, in 1910, someone informed the authorities that Kiril Nićev had a son which meant that Kiril would be forced to join the Turkish army. As a result he and his family left in the middle of one night on April 1910, leaving his business to a cousin named Nasi Naćev.

When the Young Turk Revolution took place in the spring of 1908, there was universal celebration among all the minority populations of the Empire. And indeed, it was celebrated around the world by the liberal press as having brought an end to the regime of the Bloody Sultan (Abdul Hamid II), ushering in a new phase of liberty, and equality for all the populations of the Ottoman Empire. But that revolution quickly went sour, in part, because of the European powers that took advantage of this moment to leverage their support for preserving the Ottoman Empire and pacifying the Macedonian element by further dividing them into three foreign camps (Greek, Bulgaria and Serbian) and using them to bolster their claims on Macedonia and the region.

After the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 both factions of IMRO (Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization) laid down their arms thinking that the legal struggle to bring more freedom/autonomy for Macedonians was possible. Soon, however, the Young Turk regime turned increasingly nationalist and sought to suppress the national aspirations of the various minorities in Macedonia and Thrace. This prompted most IMRO leaders to resume the armed fight in 1909. Many from Zelenich joined in this new armed struggle against the Turks in 1910 -1911 in the Macedonian-Edirne militia in Thrace.

Debate over Schools and Churches

The ruling Ottoman Turks were renowned for playing the Balkan States and their church organizations against one another. Although both the Patriarchate and Exarchate enjoyed favour with the Ottoman rulers during certain periods, it was the Greek Patriarchate that maintained long-standing ties with the Ottoman Turks and the relationship especially flourished after the 1903 Ilinden Rebellion.

Initially the churches of the Balkan States sent bishops and priests into the cities of Macedonia and sought to recruit priests from the local population in order to expand their church presence into the countryside. Native Macedonians were considered essential, as foreign priests proved to have been ineffective in the countryside villages. Most villages contained a family known as Popovci (Pop, priest in Macedonian), and in such families it was an expectation that one of the sons would become a priest. Generally priests were not permanently located in the one village, but conducted religious services in a group of villages. In Zelenich there were two Macedonian priests and both worked at St. George. St. Demetrius had a local Macedonian but this church aligned with the Patriarchate.

Communication between priests and villagers in the Bitola (Monastir) region villages was exclusively in the Macedonian language, regardless of which respective church the priest was employed by. In the case of Exarchate priests, church services were routinely conducted in Old Macedonian, and other parts of the service were conducted in the everyday Macedonian language. It was uncommon for Exarchate village priests to conduct services in other languages. Some Patriachate priests appear to have been fluent in Greek and conducted at least a part of the service in the Greek language, but it was also common for Patriachate priests to include everyday Macedonian in the service.

Macedonian villagers did not understand services conducted in Greek. Generally village priests appear to have poorly understood the official languages of the churches they were employed by. Brailsford considered the average village priest to be not a particularly distinguished individual. Most were totally uneducated and led the life of the peasants and could read enough to mumble through the ritual, and write sufficiently well to keep the parish registers. In Zelenich, St. Demetrius was used by four Patriarchist family supporters but the service was conducted in the local Macedonian language.

The Exarchate and Patriarchate competed for adherents, but it was easier for the Greeks because they had more money; they could find a poor family and get them to attend their church through the payment of money and food and this was the case in Zelenich. Papa Hristo Economidis was paid 8 gold Italian liras a month to follow the Greek Patriachist church. He was formally known as Pop Hristo Nichev but changed his name and became a Greek priest. His brother Nikola Nichev did not sell his faith (Vera in Macedonian) and promoted his Macedonian identity.

By changing his identity, Papa Hristo Economidis also started celebrating specific Greek saint days. These were different from the local saint days celebrated by the Macedonian villagers. On many occasions when Papa Hristo would celebrate a Greek saint at St. Demetrius, his brother Nikola Nichev would take the manure out of his barn and do work on that day. When ever Nikola would celebrate a Macedonian saint day, his brother Papa Hristo would do work such as white wash his home. This went on for years. Thus, while the macrocosm split was occurring in all of Macedonia, the microcosm split had already occurred for the brothers Nichev in Zelenich.

This was not the case for the rest of Zelenich and in most cases rural Macedonia as collective celebrations such as the village saint’s day continued to be celebrated by all villagers, regardless of political leanings. There was no modification of customs and traditions corresponding to Exarchate or Patriarchate jurisdiction. It was of no consequence what party the people belonged to: ‘everyone spoke Macedonian at home and in the village, customs and traditions remained unchanged and were identical in all families except the Nichev brothers. There was no separation into two groups in villages, for instance, the traditional Koleda (Christmas eve) bonfire at the height of the Exarchate and Patriarchate rivalry continued to be jointly celebrated in villages.

Schools

Alongside the struggle to establish and expand their own religious jurisdiction in Macedonia, the external Balkan States attempted to reinforce and support their respective positions through the establishment of educational institutions. Vast sums were spent by the governments of Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia to finance campaigns aimed at attracting children from the Macedonian Christian population to their respective Greek, Bulgarian and Serb schools. Religious jurisdiction was utilized in support of ethnographic and statistical data. The Balkan States recognized that through the establishment of schools in Macedonia, they could strategically use the number and location of ‘their’ schools as evidence to demonstrate to Europe that their particular population was inhabiting Macedonia, or specific regions of the land, in accordance to their territorial aspirations.

Educational activities sponsored by the Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian governments had divisive consequences for the unity of the Macedonian people, with every attempt made to replace one domination with another and to instill a new sense of identity upon Macedonians. Macedonia was transformed into an arena where rival parties battled for the minds of generations of Macedonian children. But even with these foreign teachers, students did not possess the basic language skills to speak Bulgarian, Greek or Serbian. They continued to speak their native language (Macedonian) amongst themselves and their teachers.

The Greek Patriarchate school system failed to achieve its aim of introducing the Greek language to Macedonian children in the Monastir region, according to a 1901 Greek Patriarchate letter by the Monastir Metropolitan Ambrosios.

Originally, the Bulgarians attracted students to their Exarchist schools because attendance was free and you had to pay to send your kids to the Greek Patriarchist schools. But in the early 1900s especially after 1903, the Patriarchate targeted poor families through the payment of money and food. Macedonians, Vlahs, and Albanians were bought to be pro-Greek and to send their children to Greek schools. Serb support was usually obtained only after considerable expenditure of cash; children, for example, were encouraged to attend Serb schools by the free provision of food, books and even clothes.

The Ottoman administration tried to regulate the debate over schools and churches through the law on religion, issued on 15 June, 1910. The law regulated the re-distribution of Patriarchist and Exarchist ecclesiastic property and schools based on the number of local supporters. In Zelenich St. George’s was allowed to stay with the Exarchist side and had two Bulgarian sponsored schools that taught students Macedonian, not Bulgarian. The four families who wanted to join the Patriarchist side were allowed to use St. Demetrius and they had a Greek school.

According to the secretary of the Zelenich Dimitar Mishev (“La Macedoine et sa Population Chrétienne”) in 1905 there were 1656 Macedonian Exarchists, 192 Macedonian Patriarchs and 102 Gypsy Christians in the village and two Macedonian and one Greek school. The teachers in Zelenich were V. Pliakov (villager), Bl. Tipev, G. Drandarov, L. Dukova, A. Hristova, B. Karamfilovich and D Ghizova (villager) . In 1907, the Macedonians in Zelenich had a church in which two priests served. According to Hristo Silyanov, Zelenich was a beautiful, large village, with a more urban than rural atmosphere and many men wore trousers with tame, receptive, and friendly people.

Churches

According to the 3rd article (Law on Religion) the local church belonged to the community that built it, if its proportion did not decrease below 33%. If the proportion decreased below 33%, the church and the school had to be given to the community in majority, but the other community had the right to erect a new sanctuary. According to the 4th article, in settlements with more than one existing church, churches had to be divided between communities, unless the proportion of the smaller one decreased below 33%. If any community converted to the new religion after the enforcement of this law, they had the right to erect a new building for religious purposes at their own cost.

In Zelenich, the majority (over 95%) affiliated themselves with the Exarchist church and according to the ‘Law’ the Patriarchist had to give up St. Demetrius and build a new church but they were left to use the church for some unknown reason. Possibly the amount of violence in the region forced the majority Exarchist to accommodate the Patriarchist and avoid another “Bloody Wedding.” But this type of accommodation did not occur in other villages of the region. Patriarchist (Greek) priests assigned to other religious communities refused to baptize the children of ‘Exarchist’ or ’secessionists’ or to bury the dead. The behaviour of these priests challenged the most sacred right of human beings – pleading for and praising God according one’s own customs.

Zelenich also had a mosque that was used by the local Zelenich Muslims. They had originally settled in the village in the mid 1400s and the first account of Muslims were identified in the Ottoman census of 1481. In 1900, there were 500 Muslims who according to oral stories lived in harmony with their Christian villagers. Their voices are absent from this narrative and we need to hear from their ancestors who were moved to the Izmir region of Turkey after 1923.

Importance of Religion

Religion was important in forging national identities because it superseded any ideological or ethnic alternatives in terms of its potential for unifying or dividing the rural Christian population. Religion as dogma was not nearly as important

as the daily practice of the local religious practices of native Macedonians.

The symbolic nature of many of the conflicts centring around sacred spaces and the clergy was not simply coincidence but a deliberate motion aimed at exploiting the rules, customs, and practices through which people made sense of there world. Acts such as defrocking a priest, confiscation of liturgical books, denial of sacraments, and the theft of a ceremonial robe were important not in and of themselves but because they struck a chord by directly usurping the system of symbols that the Macedonians had been using as a bridge between spirituality and everyday existence.

Targeting a church during mass was not a random act of violence but one designed for maximum impact, spiritually and physically, and for replacing communal coexistence with communal boundaries, enforced by guns if necessary. The churches in essence, became the battle ground for the souls and faith of the Macedonian people and those who controlled these sacred places then controlled the schools where we have the influence and assimilation of the heart and minds of the young.

Promoting Muslim Policy

By late spring of 1909 the radicals of the Young Turk leadership shifted their focus of interest into promoting a Muslim policy, inasmuch as they became more open towards the religious fanatic urban groups. They initiated secret negotiations with the local denominational leaders in secluded mosques. The Young Turks’ idea was to create a secret Muslim organization modelled on IMRO, with its own regulations, which could organize trustworthy and able Muslim men into combat teams after the Christian fashion. They planned to store the necessary weapons in the mosques. With this step the Young Turks wished to win the allegiance of the fanatic Muslim communities, to suppress the moderates within the party and to prepare for an open armed conflict.

However, the demands of the rural Muslim landowners for more transparency and fair practices needed to be tackled as well. Restlessness was on the increase in the kazas, as these areas were virtually ruled by irregular troops or by the IMRO, where the tension between Muslims and Christians escalated the most. This was n ot the case in Zelenich as previously stated, they lived in harmony their fellow villagers. But, the Bishop of Kastoria (Kostur) took advantage of this tension by bribing poor Muslims and started hiring Muslim fanatics to assassinate prominent Macedonian Exarchists.

On one afternoon a Muslim named Suli decided to visit his fellow villager friend, Dine (Constantine) Tsilkov. As they were having a traditional Turkish coffee, Dine’s son Kuzi positioned himself three times behind the Muslim and raised an axe he was holding all the while nodding at his father for approval to cut the Muslim’s head off. Each time Dine Tsikov motioned his head side to side indicating, no! Before the Muslim got up to leave, he told Dine that Bishop Karavangelis was giving him 10 gold coins if he were to kill Dine but, because he was his friend and he had worked for Dine, he declined the offer. At that moment Dine replied by saying that while they were drinking coffee his son Kuzi motioned to chop his head and throw his body in the oven but because of their friendship, he too declined the offer.

Howerver, Dine Tsilkov’s fate was determined by another assassin. No sooner would Bishop Karavangelis find out about his failed attempt to bribe Sule from Zelenich, he would hire another person who had no history with Dine. Anyone who would not be influenced by the Bishop of Kastoria to change their religion and accept the Greek orthodox church, in essence, become Greek, was assassinated. This was the work of the so called men of the “Greek Orthodox Faith” in Macedonia. Hundreds of prominent Macedonians would be assassinated because they refused to become Greek, Bulgarian or Serbian.

In Zelenich, the Muslim minority was very sympathetic of their fellow Christian villagers. They had lived together for four hundred years. It was said that Muslims actually worked on the fields of Christians and they attended each others religious celebrations. The Muslim ‘Zelenichani’ even convinced the Ottoman authorities not the execute the 50 Christian men from the village (Exarchate and Patriarchate supporters) who took part in the 1903 Ilinden Uprising. The men were jailed in Monastir and after a year they tunnelled their way out escaping to other parts of Macedonia. For some reason the Christians were better off then the Muslims in Zelenich and some of the well off Christians hired Muslims to work for then planting and sowing crops.

On one such occasion, according to Katerina (Chicules) Domaschiev, the Chicules family had a store and employed a 10 year old Muslim boy. When the boy died (TB), Katerina’s grandmother paid for an iron fence to be built around the boys grave. This is just one example of the type of the harmonious mixed community that existed in Zelenich. Unfortunately, the Muslim cemetery would eventually be bulldozed by the racist and nationalist Greek authorities of the 1950s. They would build a soccer field in its place.

In order to maintain peace, the Ottoman authorities had taken steps against the broadening activity of the irregular Christian troops. At the end of 1909 the parliament in Istanbul legislated a general law to abolish all the irregular troops within the boundaries of the Empire. According to the law it was forbidden to set up irregular troops or to keep weapons at home. If caught, the Cheta (armed Macedonians)leaders were to be executed, and the Cheta members to be imprisoned. The law also declared the right for the authorities to arrest the wives and the children of the Cheta members. This law however, turned a blind eye towards the activities of the Greek insurgents from the state of Greece. They were free to roam the mountains without any reprisals. In essence, they were the secret weapon of the Turks against the Macedonian “Freedom Fighters” (IMRO) and people.

On top of this, by 1910 the central government decided to handle the problems of the vilayets (regions) and to collect the weapons with the help of the Imperial army. Besides collecting the weapons, they terrorized the local Christian villagers. The military troops would surround a village, open fire with canons, brutally beat up the terrified inhabitants and carry off the handcuffed men. After these acts, the frightened villagers handed over their weapons without resistance. On September 1910, Zelenich was damaged during the disarmament action of the Young Turks. Villagers refused to give up their arms so, the army ran-sacked the village looking for weapons. The Christian inhabitants protested to the authorities and the foreign consulates against the disarming action. They referred to the fact that without their weapons they would not be able to defend their villages against the irregular Muslim or Christian Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian mercenaries.

During this time, the Hellenization, Serbization and Bulgarization of the Macedonian villages was accomplished by money spent on purchasing land, erecting schools as well as bribing or intimidating influential local people. The disarmament action of the villages in the previous years limited the villagers from defending themselves, as a result many joined a band (cheta), since there were no weapons at home any more. Many more would be bribed to join Bulgarian, Greek and Serbian military and para-military groups.

Macedonian farmers were tired of being under the threat of the revolver in the morning by the Bulgarians, in the afternoon by Greeks, in the evening by the Serbs and the next morning by Romanians. In Zelenich it was the Bulgarians during the day and the Greeks at night. Only the Bishop of Kostur (Kastoria) Karavangelis would dare come to threaten the village but this was done with the support of Ottoman troops.

This was the case for Macedonians who did not align themselves with either the Greeks, Bulgarians or Serbs. They were a threat to their plan of attaining converts to their side. With an increase of violence, the economic situation worsened for all inhabitants and this allowed for an increase in activities of foreign insurgents (Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian) into Macedonia. They each used bribes to convince poor Macedonians to kill each other over their choice of which foreign nation to support.

It quickly becomes clear that the “Young Turks” wanted to return to an improved version of the old situation, by forcibly Turkifying the population. They created an environment of the uprisings within each village, town and city by allowing Greek insurgents to roam freely, antagonizing Bulgarian and Serbian para-military groups to fight each other and promising native Macedonians change that they did not intend on delivering. In the short run, they appeased the west by disarming Christians and promising peace but in the long run, they created an atmosphere of anarchy that ended in the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the division of Macedonia between Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria.

Self-Identification: Macedonian

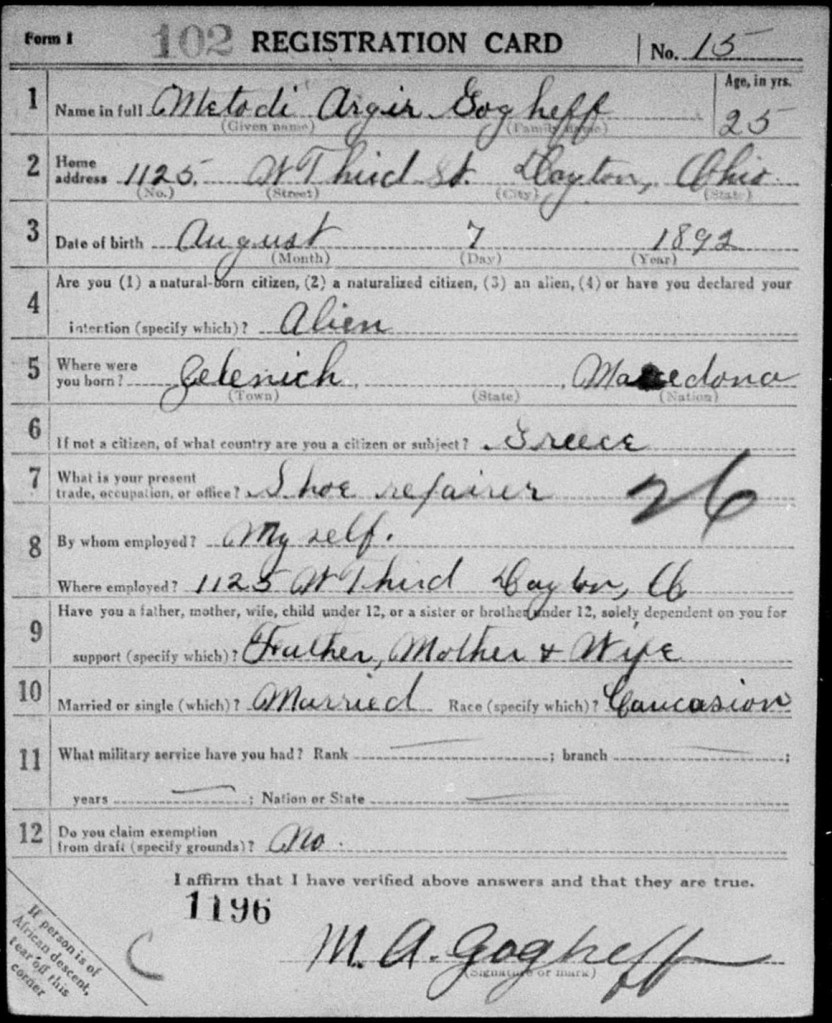

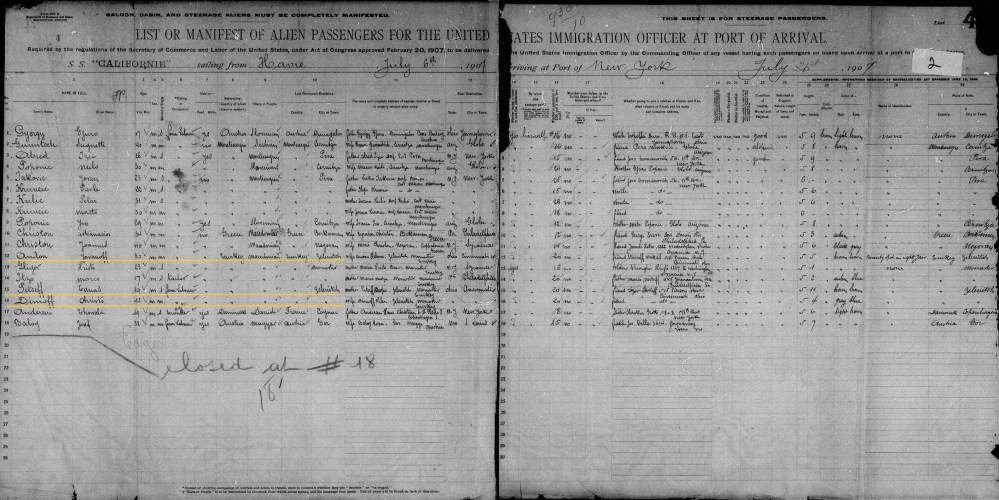

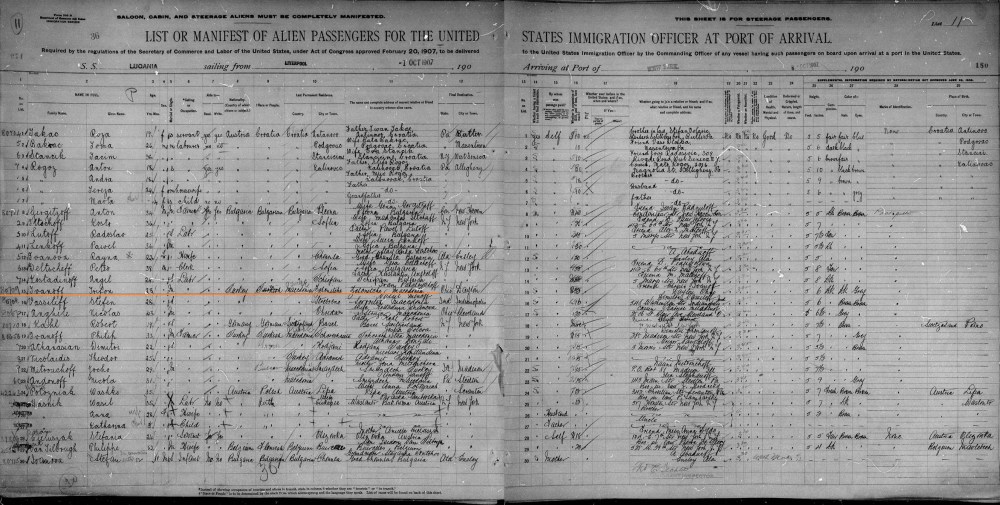

Thus began the emigration of Macedonians to the Americas. Between 1907-1915 more and more men from Zelenich migrated from the village to the USA and on their arrival there on Ellis Island the following eleven people declared themselves to be national Macedonians:

- Canas Petseff in 1907;

- Vasil Kostoff in 1909;

- Yane Kotortcheff in 1910;

- Lazar Tasseff, Stayan Miteff, Stoyan Passil, George Frengo, Stefan Georgieff, Giorgie Petroff and Stefan Vangeleff in 1912.

Below are a few examples drawn from the official list of Alien Passengers compiled by the United States Immigration Officer at the Port of Arrival.

Sources:

Anderson, F. M. (1919). The Turkish revolution of 1908-9. Mount Holyoke College |. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/boshtml/bos126.htm

Demeter, G. (n.d.). Microsocial strategies of survival and coexistence in Macedonia (1903-1912). Examples on family and community-level social strategies and government repressions. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/5297420/Microsocial_strategies_of_survival_and_coexistence_in_Macedonia_1903-1912_._Examples_on_family_and_community-level_social_strategies_and_government_repressions

Hacısalihoğlu, M. (2012). Yane Sandanski as a political leader in Macedonia in the era of the young turks. Cahiers balkaniques, (40). https://doi.org/10.4000/ceb.1192

Hansard. (1908, February 25). Macedonia. (Hansard, 25 February 1908). api.parliament.uk. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1908/feb/25/macedonia

Hovannisian, R. (n.d.). 1908-1914 shift to young turks [Video]. Facing History and Ourselves. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/video/1908-1914-shift-young-turks

Jackanape. (2006, August 30). The Balkan boundaries after 1913 [Map]. Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a2/The_Balkan_boundaries_after_1913.jpg

Karava, S. (2010, October 15). Μακάριοι οι κατέχοντες την γην: Γαιοκτητικοί σχεδιασμοί προς απαλλοτρίωση συνειδήσεων στη Μακεδονία 1880-1909. AΡΧΕΙΟ ΕΝΘΕΜΑΤΩΝ 2010- 8.5.2016. https://enthemata.wordpress.com/2010/10/17/karavas/

Lagopoulos, A. P., & Boklund-Lagopoulou, K. (2015). Meaning and geography: The social conception of the region in northern Greece. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG.

Lazarus Elte. (1910). 3rd Military Mapping Survey of Austria-Hungary [Map]. http://lazarus.elte.hu. http://lazarus.elte.hu/hun/digkonyv/topo/200e/39-41.jpg

Liakos, A. (2014). The unwashed things of Greek history and their literary laundry. Chronos, 14.

McNeill, W. H. (1969). The Greek struggle in Macedonia 1897-1913. Douglas Dakin. The Journal of Modern History, 41(3), 417-419. https://doi.org/10.1086/240441

Melissas, L. (2014). The Diocese of Moglena and Florina through the archives of the Delegation-Demogerontia (1907-1913). UNIVERSITY OF MACEDONIA SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND REGIONAL STUDIES DEPARTMENT OF BALKANS, SLAVICS AND EASTERN STUDIES, 198. Α.Ε.Μ .: Μ511013

Michailidis, I. D. (1998). THE WAR OF STATISTICS: TRADITIONAL RECIPES FOR THE PREPARATION OF THE MACEDONIAN SALAD. East European Quarterly, 32(1), 9. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296904992_The_war_of_statistics_Traditional_recipes_for_the_preparation_of_the_Macedonian_salad

Passenger manifest annotations. (2021, April 7). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/passenger-manifest-annotations

Ravindranathan, T. R. (1965). The Young Turk Revolt: Its Immediate Effects. Simon Fraser University. https://summit.sfu.ca/item/3034

Wikimedia. (1908, October 18). Cartoon from the French newspaper, “Le Petit Journal”, about the Bosnian Crisis of 1908. Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/16/Le_Petit_Journal_Balkan_Crisis_%281908%29.jpg

Zürcher, E. J. (2019). The young turk revolution: Comparisons and connections. Middle Eastern Studies, 55(4), 481-498. https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2019.1566124