The Fires within the Mountains

The mountains surrounding Zelenich were teaming with terrorist activities as competition for the hearts and minds of the people was reaching new heights. Villages that converted to the Exarchist Bulgarian church were being harassed with threats of violence to convert back to the Greek Patriachate church. Villages that remained with the Greek Patriarchate church were being pressured to convert to the Bulgarian Exarchate.

Under Ottoman regulations, if more than 50% of the population chose to switch church affiliation, they could do so legally without reprisals. But, external forces (Bulgarian & Greek) were at play trying to influence the outcome with bribes at first, then threats and finally, with killings. This was the case in the villages surrounding Zelenich especially, Eleovo (Lehovo) and Strebreno (Asprogia). First the people would choose to convert to the Bulgarian Exarchist church then, upon hearing of the switch, Greek terrorists would go in threaten and or kill the prominent Macedonians placed in power.

According to historical accounts and oral history, Zelenich was a village that always followed and promoted the local dialect of “Old Church Slavonic” in their liturgical services. This did not change after the village voted to align with the Bulgarian Exarchate Orthodox Church. The Bulgarian language was not used in church services or in the “so-called” Bulgarian school beside St. George’s church. Even the four families that chose to remain with the Patriarchate, delivered service in the local dialect and not in Greek. As a result of the strength of their Macedonian identity, foreign terrorists were reluctant to attack the village. The revolutionary activities of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization were accepted and promoted by prominent members of the village.

Zelenich and IMRO

Since its inception, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO – IMRO in English) impetus was a desire to preserve the ethnicity of the Macedonian population. Foreign propaganda had increased and there was a need to ward off the effects of such propaganda by neutralizing outside influences (Greek & Bulgarian). The idea of Macedonian liberation would save Macedonian ethnicity and would strengthen the population spiritually and economically.

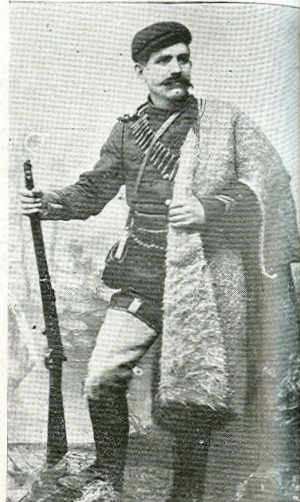

The revolutionary movement spread rapidly through Macedonia and Zelenich was one of many villages in the region that took on the cause to promote the idea of Macedonian liberation. One such group was the “Cheta” of Stefan Dimitrov who received his primary education in his native Zelenich, and finished high school in Plovdiv. He studied mathematics at the University of Sofia, but in 1900 he left and became a teacher in the Kukush region teaching the third grade and joined the IMRO.

But the “Fires Within” IMRO, between the Central Committee (who were mainly ethnic Macedonian schoolteachers), and the Supreme Committee (mainly Bulgarian Officers) lacked cooperation with significant disagreements and intentions resulting in deteriorated relations by 1900. The Supremist wanted to incorporate Macedonia within a “Greater” Bulgaria with an organized insurrection using an army of at least 20,000 men. Whereas the Centralists, wanted to “Liberate” Macedonia with an insurrection of armed revolutionary bands and the support all the people.

Just as Bulgaria had hijacked the Macedonian “National Awakening” of the mid 19th century as their own awakening to first organize priests, then teachers, to indoctrinate the Macedonians into becoming Bulgarians, now they were to use their army officers to infiltrate IMRO and take over the planning of the insurrection. Thus, began a concerted effort to destroy the Central Committee members by informing the authorities (Turks) of their identities. The arrests of the Central Committee and the decisions and actions of the Supreme Committee to take over IMRO and begin an armed uprising was a sign to Macedonians that the Bulgarians were not to be trusted.

Thus, local committees were warned to avoid any activities that would attract the attention and revenge of Turkish authorities. All the while, preventing a premature uprising which would be suicidal for the cause – Liberation of Macedonia. The leadership of the Central Committee felt that the Bulgarian government harboured the desire to rule Macedonia, not liberate it! As such, they refused to take money from the Supreme Committee and the Bulgarian government, as that money would have “strings” attached to it.

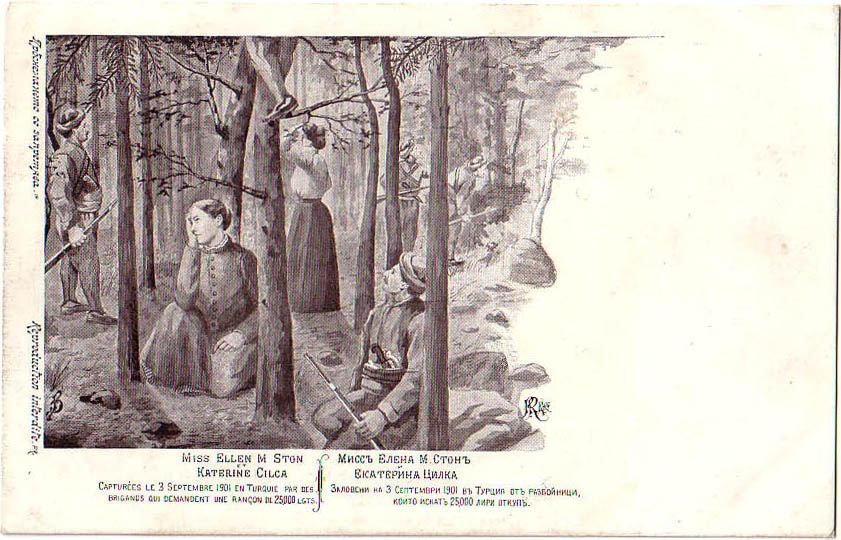

The Miss Stone Affair

As a result, in 1901, the Central Committee was forced to look at other means and sources to liberate Macedonia, independent of Bulgaria. A system of small robberies in the past hurt IMRO’s reputation so, they decided to kidnap a foreign Protestant missionary believing that the Turkish government would be forced to pay a ransom quickly in order to avoid international complications. On September 3, 1901, an American, Miss Ellen Stone was seized and a ransom of 25,000 lira ($100, 000) was the demand. The Miss Stone Affair became America’s first modern hostage crisis.

The goal of the kidnapping was to receive a heavy ransom and to aid IMRO in their struggles for the liberation of Macedonia from the Turkish yolk. In the end, Miss Stone and Katerina Tsika were released for a ransom of 14,000 Turkish gold lira on January 18th, 1902. The money was used to finance the insurrection against the Ottoman in Macedonia.

Sava Mihajlov, Yane Sandanski, Krastjo Asenov and Hristo Chernopeev

Greek and Bulgarian “Anti-Macedonian” Struggle

The two exponents involved in the “Anti-Macedonian” struggle were the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the new Kingdom of Greece. In the 19th century each entity had different goals and how they were to achieve these goals. The Patriarch aimed primarily at maintaining a theocracy of the Greeks ever since the Turks gave them sole ownership over all Balkan Orthodox Christians in 1767. This not only included all the Greeks but also, Macedonians, Albanians and Vlachs. On the other hand, the Greek National State, with its own autocephalous church, thought in terms of extending its frontiers.

At the dawn of the 20th century, these two exponents would come together to secretly fight against the native peoples of Macedonia. The systematic effort made by the Greek state at the beginning of the 20th century, to strike at the national-democratic separatist movement of the Macedonians. Money and weapons were used extensively to set up and send armed mercenary groups to Macedonian territories to terrorize the Macedonian population and stop the process of Macedonian ethnogenesis.

They exploited the Rum system of classifying all orthodox Christians as Greeks (Macedonians, Albanians and Vlachs) in terms of religion and used this as an excuse to invade Macedonia under the guise of saving Greek orthodoxy and Hellenism from the Bulgarians and the Bulgarian Exarchate.

Even though the churches in the main towns and cities (urban areas) of Macedonia used Greek for liturgical services, the rural areas were purely Slavonic, using “Old Church Slavonic” (Macedonian) and not Bulgarian. But, the “National Macedonian Awakening” of the 19th century threatened the Greek theocracy of the Patriarchate in Constantinople.

The Greeks were first to exploit Macedonia with their Patriarchate church after 1767. In the late 19th century the Bulgarians entered the arena (1870) with the Exarchate church which gave them the legal right to use their own language (Bulgarian) in the newly autonomous Ottoman region of Bulgaria after 1878 (Treaty of San Stefano). Thus, started the religious battle between Greece and Bulgaria. The former trying to preserve their privileged position and the latter to promote their newly acquired privilege, both, with no regard for the wishes of the native Christian peoples of Macedonia.

Thus, the ecclesiastical battle entered a new phase, that of using brides, threats and eventually the murder of those who did not remain with the Patriarchate Greek church and those who would not convert to the Bulgarian Exarchate church. Each, Bulgaria and Greece using their military officers in clandestine operations with the help of native Macedonians to liberate Macedonia from the Ottoman bondage. Both Greece and Bulgaria exploited people’s desire for freedom to further their national interests and to expand their own state boundaries with little regard to the majority Macedonians and minority Albanians and Vlachs.

People now had to choose their identity in becoming Greeks by supporting the Greek Patriarchate church or becoming Bulgarians by supporting the Bulgarian Exarchate church. This, irrespective of their past history, culture and true ethnicity as Macedonians, Vlachs and Albanians, with each their distinct languages, customs and cultures. It is said that the first casualty of war is the truth, and, in this battle, we also have the loss of the hearts and minds of the people with the loss of their distinct identities.

Greek Influence – Kastoria (Kostur) Metropolitan Germanos Karavangelis

As early as 1900, Germanos Karavangelis was appointed Metropolitan of Kostur by the Greek Ambassador Nikolaos Mavrokordatos. Karavangelis, with the help of the Bitola consul Stamatios Pezas, began a clandestine battle against the growing Macedonian freedom fighters and the IMRO in the area. At that time, many villages had chosen to support the Bulgarian Exarchist church and since his appointment, he began to pressure those village/towns to return to the Patriarchist church.

At the same time, he came into contact with armed leaders that had so far collaborated with IMRO (the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization), mostly Macedonian-speaking people, such as Kotas the muktar (headman) of Roulia (today Kota) and Vangelis from Strebreno (today Asprogia) in order to organize guerrilla bands that would attack Exarchist villages and confront Macedonian voivodes (freedom fighters).

He bribed Kotas for the Greek cause, giving him a salary of 8 lira a month and sending his children to school in Athens. In 1901 he attracted other voivodes for his cause, among whom were Gele Tarzianski, Georgi Sider and Vangel Georgiev. The latter organized the first Greco-Roman detachment together with the Andarti Georgios Perakis and carried out the first criminal actions against local Macedonians. He gradually achieved success in the southern Macedonian villages in the region of Bogatsko, in the non-Macedonian villages in the north such as Lehovo with the use of bribes and persuasion.

In 1902, Ion Dragumis (father-in-law of Pavlos Melas) joined the diplomatic community and was sent to Bitola as a consul, where his main task was to create secret committees for armed struggle against the Macedonians. With anti-Bulgarian Exarchist rhetoric, he encouraged the Patriarchists to ethnically cleanse the Macedonians. He created the secret organization “Amina” (Defense) together with Philippos Capetanopoulos, Theodoros Modis, Christos Dumas and others, whose status included the idea of a guerrilla movement. Arms began to be supplied from Greece and Greek mercenaries from Crete and Mani joined by detachments of Albanians and Turks (numbering about 50), accompanied Bishop Karavangelis, travelled around the Kostur and Lerin area spreading their propaganda and rain of terror in the name of the Greek Patriachate church.

Bishop Karavangelis vigorously took advantage of his relations with the Ottoman authorities, by using them as shields when ever he entered a town/village to threaten them with violence/death if the Christian population did not convert to the Patriarchist side. Karavangelis first encounter with the village of Zelenich occurred in June 1903, when he entered the village with 50 Ottoman gendarmerie (security force with law enforcement duties). He requested to conduct Sunday church service in Greek but was refused by the village muktar (headsman/ mayor). As a result, Karavangelis threatened to burn down St. George church so, the muktar reluctantly, had no choice but to sit and watch as Karavangelis conducted the service and them left with his Ottoman bodyguards.

Oral History – Story by Katerina (Chicules) Domaschieff

Later in 1903, Karavangelis would try to inflict his wrath onto the people of Lubetina (today Pedino) beside the village of Aetos. Lubetina was a mostly Christian Gypsy village which spoke Macedonian and had church service conducted in Macedonian. After many unsuccessful efforts to convince the villagers to convert to the Patriarchist side, Karavangelis sent his agents to take care of the matter.

“At that time the village was having a festival for its Saints day (St. George) and all parishioners would have been attending church service. A couple of days before the celebration Maria (Grcheva – from Zelenich) Chicules who had married Vani Chicules (residing in Aetos) happened to visit her friend, the priest wife of Lubetina. While there the priest was called out by two men who were whispering to him and they handed him a paper, grandmother noticed it. Something was telling her that something was wrong. She got up afterwards saying she stayed too long, stood up to leave and as she passed the priest she brushed against him, either it dropped or it was sticking out and grandmother picked up the paper, took it home, called her grandfather to read the letter, it said from the Bishop of Kostur (Karavangelis) to burn the church when everyone was inside during the celebration of the Saint day. People would come from all over the area to celebrate. To burn it, over a thousand people were to come and grandfather went from house to house (in Lubetina) to warn the people. Afterwards, Karavangelis was so upset that he sent agents to burn the Chicules house in Aetos. They had 5 children, 2 boys and 3 girls. The 2 boys were visiting relatives in Zeleniche. The 3 girls (twins + 1) were in Aetos, to save the girls, grandmother put them in the chimney so they would not get burnt but they said they could smell the horses the cows (the meat). Grandfather wasn’t home at the time; he had a small store buying supplies and was also assisting the IMRO as a courier. When he came back he found everything burnt down and that’s when they moved to Zeleniche” (Katerina (Chicules) Domaschieff)

Germanos Karavangelis was one of the most important agents of the Greek expansion into western Macedonia. The Anti-Macedonian organizations of Athens and the army officers coordinating the terrorist activities were in constant contact with him. Macedonians were not the only ethnic group that were terrorized by Karavangelis, so were ethnic Vlachs, and Albanian Christians. In 1905, Orthodox priest Kristo Negovani in his native village conducted the divine liturgy in the Albanian Tosk dialect and for his efforts was murdered on orders from Bishop Karavangelis who had condemned the use of Albanian. In 1907, provoked by his activity, the Turks demanded from the Patriarch – and achieved – his removal from Macedonia.

Bulgarian Influence

It is “history making” which creates opportunities – through an invented past – to reinvent the present … My father, my grandfather and my great-grandfather were called Bulgarians by misunderstanding, but that doesn’t mean I have to stay in the dark like they do in terms of my nationality. (Krste Misirkov)

Bulgaria on the other hand, had the advantage of similarities in culture, customs and language and were able to take advantage of indoctrinating the young minds of Macedonians who were sent to be educated in Bulgaria. The “National Macedonian Awakening“ was hijacked by Bulgaria into becoming a “Pan-Slavic” movement in liberating Macedonia from the Turks and Greek Patriarchate. Even the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO – 1893) who’s main goal was to win autonomy for Macedonia from its Ottoman Turkish rulers was weakened by Bulgarian influence when they formed their own Macedonian organization, the Supreme Committee in 1895.

IMRO ‘s main goal of, “Macedonia for Macedonians” was challenged by Bulgaria’s goal of annexing Macedonia into a greater Bulgaria. The Supreme Committee was made up of Macedonians who identified themselves as Bulgarians and was controlled by Bulgarian military officers, some also being native Macedonians. Most of the Central Committee in IMRO consisted of teachers and an educated class who served the Exarchist school organization but, were entirely hostile to its aims and, merely used it as a means of earning a living, of coming into contact with Macedonian youth, and providing themselves with a cover for subversive activities in the liberation of their people.

The village of Zelenich not only had numerous individuals who took up the cause in organizing and arming themselves into secret IMRO bands, but also, it continued to use Macedonian in liturgical services as well as having built a “Bulgaro-Macedonian” school with locals as teachers who also taught using “Old Church Slavonic,” the local language and not Bulgarian.

By 1900, there were more than 100,000 Macedonians in Bulgaria, a large part (20,000) having settled in Sofia. Most were young men who were more adventuresome and the more intelligent of their generation. A large number of teachers came from Macedonia and every year hundreds of Macedonian students went to Bulgaria for higher education. Many families from Zelenich sent their son’s to achieve a higher education abroad once they finished primary school in the village. Vane Pliakes was one such man who even returned to teach in the village.

“One third of the officers in the Bulgarian army, some 15,000 officials out of a total of 38,000 and 1,262 priests out of a total of 3,412 were Macedonians.”

I L I N D E N A U G U S T 1 9 0 3

The Ilinden Uprising was not the first armed attempt to establish a degree of autonomy in the territory of Macedonia. The Uprisings of Razlog in 1875, of Kresnensko and Razlosko in 1878, and of Gorno-Dzumajskiin 1902 had already raised the issue. Ilinden surpassed these earlier ventures in that, it lasted longer and achieved more of its goals — if only temporarily. With the founding of the Krusevo Republic in particular, a precedent was set for Macedonian self-government which would remain a source of national inspiration long after the Uprising had been crushed.

The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (VMRO – IMRO in English) and the Ilinden (St. Elias’s Day) Uprising on 2 August 1903 (July 20 in the old Julian calendar) occupy a sacred place in Macedonian history. The foundations of such an association, which became the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, was the work of young men who met in Salonika on 23 October 1893. Their main aim was the liberation of Macedonia and its people and the establishment of an autonomous and eventually independent homeland or an equal partnership in some sort of Balkan federation.

Such a state would liberate the Macedonians from Ottoman domination, and would also free them from the devastating foreign Bulgarian, Greek, and Serbian propaganda, intervention, and terror, which split the Macedonians in family, village, town, and homeland into antagonistic ‘‘parties,’’ or camps, and threatened annexation or partition. The movement identified itself and all Macedonians, irrespective of church affiliation, as Macedonians, as a distinct ethnic entity related to, but different and separate from, the Bulgarians and Serbians.

The VMRO’s immediate task was to prepare the restless masses for revolution, and so it set up a secret, hierarchical network of committees to that end. The organization was to be sovereign and independent and free of foreign influences and interference. A central committee was, in name at least, the highest decision-making organ. There were regional, district and local organizations that divided Macedonia into revolutionary regions, each with a regional committee in charge.

The village of Zelenich, had its local chief (voivode) that organized armed units (Ceta) consisting of committee (Komita) members as a standing paramilitary group. The “Ceta” performed police and security duties for the organization and, most important, readied the villagers for rebellion. Some of those involved are mentioned later in this period section.

Despite all the organizational developments, the VMRO was far from ready for the planned popular revolt. It did not gather the financial resources to procure the arms and train the masses, and the army of the revolution. The conservative and practical peasants were hesitant to risk joining the struggle unarmed and defenceless. Overall, the VMRO had no political or diplomatic allies, Bulgaria, Greece and Serbia were openly hostile to it and its aims.

1894 Greek, Serbian & Bulgarian Anti-Macedonian Organizations arise!

In 1894, a secret organization called the National Society (Ethniki Hetairia) was set up with support from the Greek government, army officers and wealthy and influential citizens. In Serbia, the Political Education Department (Politicko prosvetno odelenie) was formed to direct Serbia’s efforts in Macedonia. The great successes of the Exarchate and Bulgarian diplomacy in Macedonia inspired the creation in Sofia of the Macedonian Supreme Committee (Makedonski vurkhoven komitet) which was organized under the auspices of the Bulgarian crown and was essentially a Bulgarian instrument which falsely represented the Macedonian immigrants in Bulgaria.

Even with these extreme foreign influences, the VMRO movement identified themselves as Macedonians, irrespective of church affiliation, and as a distinct ethnic entity different and separate from, the Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek ethnos and genos. As the movement became stronger in its aims and goal internally, and as foreign diplomats and politicians became more vocal with the call, “Macedonian for Macedonians,” Bulgarian, Greek and Serbian intervention grew.

Officially, Bulgaria disliked the VMRO’s (Saloniki 1893) Central Committee’s aims and sought to undermine its independence by creating a second wing called “The Supreme Revolutionary Committee (Sofia 1895 – also called the Vrhovists – Supremists). This wing only used talk of Macedonian autonomy or independence as a cloak for its real aim of Bulgarian annexation of Macedonia. The “Central Committee” of the VMRO at first worked in secrete, organizing and arming the population of Macedonia. But, the “Supreme Committee” members had become indoctrinated into the Bulgarian narrative for Macedonia, sought to take it over by discrediting the organization among the people, betrayed or physically eliminated some of its leaders and hindered its activities and sabotaged its development with armed raids and premature and doomed uprisings.

By January 1902, Ottoman authorities in Salonika arrested more that 200 VMRO activists and this opened the door for more Bulgarians (anti-Macedonians) to infiltrate the organization and influence decision making. A Bulgarian named Ivan Garvanov took control of the VMRO’s reins and abandoned its policy of patient, careful and systematic preparation and called for an immediate uprising. At the end of December 1902, Garvanov announced a VMRO congress in Salonika in early January 1903 to decide whether to launch the uprising in the spring. At the gathering, Garvanov pressured those present to agree with his proposal and he even made promises that the Bulgarian army was ready to aid the insurgents.

In the end, the opponents were unsuccessful, and the congress agreed to call for a revolt in the spring. This decision divided the VMRO leadership at all levels. Its best-known figures, such as Delcev, Petrov and Sandanski, rejected it. In fact, Petrov, denounced it as “Supremist” inspired and destructive. Goce Delcev was the top-ranking leader who could have mounted a successful opposition campaign but, he did not attend the congress fearing assassination from Bulgarian influenced Supremists.

In the memoirs of Vojvoda Lazar Dimitrov, published in 1930, he remembers meeting Delcev and discussing the upcoming fight against the Ottomans. “He told me that he met Gruev and discussed the proposal. The end result was that he, Goce, agreed to have an uprising at the end of the Summer, but in a guerrilla style, without mass recruitment and a standing army battle. This put an end to the disputes over the character of the uprising and we decided to focus on its preparations. We departed wishing well to each other. It was the last time I met Goce”, wrote Dimitrov.

Evidence suggests that Delcev was planning to mount an opposition at a congress of regional leaders, near Seres on St. George’s Day (6 May 1903). When he was on his way there, Ottoman troops attacked him and his “ceta” in the village of Banica. Delcev suffered serious wounds and died on 4 May. There are no satisfactory explanations of the ambush. It is possible that an Ottoman spy discovered Delcev’s plans or that Garvanov betrayed them to the authorities. In any case, the VMRO lost its most charismatic figure, a man who had come to symbolize the spirit and aspirations of the organization. Delcev’s death removed from the revolutionary movement its most popular and effective leader and the most potent and influential opponent of Garvanov.

The Bulgarians set in motion something that the Macedonians were not prepared to ignite but had no choice to continue but under their own control.

By May of 1903 a VMRO congress in Bitola decided that a reversal of the Salonika congress was not possible as the atmosphere in Macedonia grew more tense and violent and had drawn the attention of the great powers. VMRO’s “Central Committee” leaders agreed to launch the revolution after the harvest and not in the spring as the “Supreme” Committee and the Bulgarians wanted.

Then in the evening of 2 August 1903 at ‘Ilinden’ (St Elijah’s Day) the revolution broke out in the Bitola (Monastir) vilayet, which remained its focal point. The insurgents attacked estates and properties owned by Muslim beys, destroyed telephone and telegraph lines, blew up bridges and important official and strategic buildings, and, in some places, attacked local garrisons. One of their earliest successes was the capture on 3 August of Krusevo, a picturesque mountaintop town 1,250 meters above sea level, with a largely Macedonian and Vlach population of about 10,000. There, under Nikola Karev, the rebels established a provisional government, issued a manifesto reiterating the revolution’s aims, and declared the Krusevo Republic.

As Henri Noel Brailsford, a British journalist who was in Macedonia in 1903 and 1904, wrote: ‘‘there is hardly a village [in the Monastir vilayet] which has not joined the organization.’’

Large-scale revolutionary actions took place elsewhere in the Bitola vilayet, in the counties of Kastoria (Kostur) and Florina (Lerin); in various localities in the counties of Ohrid, Kicevo, and Prilep, revolutionary authorities emerged. The vast majority of the non-Muslim inhabitants of the vilayet supported the revolution. The plan was to engage the Turks in guerrilla warfare, “using terrorist and anarchist tactics,” in a way that would prevent superior Ottoman forces from quashing the Uprising quickly. By drawing out the conflict, it was hoped that the Great Powers would eventually be driven to intervene on Macedonia’s behalf. In a handful of districts (Klisura, Neveska (Nymphaio – the Zelenich area), Smilevo, and Krusevo) popular enthusiasm propelled the Uprising beyond the level of partisan warfare envisioned by the General Staff: Turkish garrisons and bureaucrats were driven out completely, and autochthonous, revolutionary governments were installed with Krusevo being the most important.

Excerpt from Macedonia: Its Races and Their Future H. Brailsford 1906

The insurrection of 1903 was a demonstration in which the whole village population shared, men, women, and children. Those who bore the full weight of the insurrection were the non-combatants whose courage and sacrifice to the ideal of liberty was unparalleled.

Every village which joined the revolt did so with the knowledge that it might be burned to the ground, pillaged to the last blanket and the last chicken, and its population decimated in the process. That the Macedonians voluntarily faced these dangers is a proof of their desperation.

Life had lost its value to them and peace its meaning. In many of the districts which revolted the peasants had so little doubt of what was in store for them that they abandoned their villages in a body on the first day of the insurrection. The young men joined their bands accompanied by a few women, who went to bake for them, and in some cases by the women-teachers at the town schools, who were organized as nurses for the wounded.

The older men, the women, and the children sought refuge in the mountains and the woods. They took with them as much food as they could carry, drove their beasts before them, and buried their small possessions. The sick and the aged frequently remained behind, imagining that their weakness would appeal to the chivalry of the troops.

Zelenich & Ilinden

Zelenich, like most Macedonian and Arumanian villages in southwestern Macedonia, took an active part in the Ilinden Insurrection of August 2, 1903. The men of the village fought under the command of Kocho Tsonkata and Lazo Dimitrov Bitsinov. After a battle near the Cherna Voda area of Zelenich, the Chetas, Stefan Kotorchev, Vasil Kotorchev, Mihail Kolinov, Yanko Chavkov and Petre Masin were killed. The villagers Georgi Boglev, Gele Nanov and Hristo Dinev were killed in the village itself, and on August 16 the Illyrian Dine Nanchov was killed.

When the insurrection was crushed, a division of Turkish troops arrived and wanted to burn Zelenich to the ground. Fortunately, some influential Turkish residents of the village managed to talk the Turkish commander out of carrying out his plan. These Turkish villagers realized that the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization fought not against them but, against the corrupt Ottoman government. Nevertheless, five residents were arrested and exiled to Kiarbekir in Asia Minor and fifty were locked up in Bitola’s prison. However, after a year in prison, 80 imprisoned Macedonians, fifty of them who were from Zelenich, dug a tunnel under the thick walls of the prison and the participants succeeded in getting away alive. One of those villagers was Ivan Pliakov, the schoolteacher and grandfather of Steve Pliakes.

Dayton Daily News, 11 Sept 1903 – Consular report from Zelenitch that 300 insurgents who had surrendered after being surrounded were massacred by Turkish soldiers. [Dakin]

An official publication of the VMRO in 1904 claimed that 26,408 fighters took part in the period from 29 July to 19 November 1903. More than two-thirds of them, or 19,850, fought in the Bitola vilayet, 3,544 in the Salonika, and 1,042 in the Skopje vilayet. The extent and intensity of the revolt surprised the European powers, the neighbouring Balkan states, and the Ottoman authorities. However, it was also obvious from the outset that without external assistance, a decisive diplomatic intervention by Europe or military help from the Balkan neighbours, particularly Bulgaria, the premature, badly organized, and poorly armed uprising would fail.

According to some accounts, this rising was forced by the Bulgarian War Office (acting on Russian encouragement) on the hesitant leaders of the VMRO, who thought that the time was not yet ripe for open action. In any case, after initial successes the insurgents were ruthlessly crushed by the Turkish army, as Bulgaria watched.

The Bulgarian army stood waiting at its border without intervening to assist the revolutionaries after Ilinden.

According to French “Helenist” and popular politician, Victor Berard, the Bulgarians had their spies in Macedonia, followed the preparations for the insurgency and when it broke out, they stopped their army at the Macedonian border without intervening. He goes on to state that although the Bulgarians did not participate in the insurrection, they maintain, against all historical evidence, that the Republic of Krusevo, proclaimed during the insurrection, would be their work. It is clear that by their own admission, that they were strangers to the insurrection movement in Macedonia. But this historical fact did not prevent their historians from trying to “Bulgarize” the key players, as well as, the Republic of Krusevo which represents the historical foundation of the contemporary state of Macedonia.

Europe wished to preserve the status quo; each of the Balkan states claimed Macedonia and the Macedonians. Hence the rebels had to face alone the Ottoman empire with 350,931 soldiers by mid-August, concentrated in Macedonia 167,000 infantrymen, 3,700 cavalrymen, and 444 guns. After defeating the insurgents at Krusevo, the Ottoman army moved systematically against the other centres and gains of the revolution in the Bitola vilayet and elsewhere in Macedonia. Zelenich was one of the first villages to be hit as it stood at the foothills of “Vicho Planina.”

For nearly three months, “Macedonia writhed in the throes and flames of Ilinden.” The immediate consequences were disastrous for Macedonia and its people, especially the Macedonians and the Vlachs. Data concerning death and destruction vary greatly, but it appears that as many as 8,816 men, women, and children died; there were 200 villages burned, 12,440 houses destroyed or damaged, and close to 70,836 people left homeless.

According to professor Andrew Rossos from the University of Toronto, in his book, Macedonia and the Macedonians:

The psychological and political impact of the ill-timed and failed uprising is beyond calculation. The optimism, high hopes, and expectations for a free and better life that the VMRO and the revolt generated gave way to ‘‘panic, demoralization, disillusionment and hopelessness.’’ The VMRO fragmented into antagonistic factions keen to destroy one another and never regained its pre-Ilinden strength, prestige, and unity of purpose. This is very evident in the period after Ilinden up to 1908 and the “Young Turk Revolt.”

Nonetheless the Ilinden Uprising represented a landmark in the history of the Macedonians. It was the first such organized effort bearing the Macedonian name, taking place throughout the territory, and calling for a free state encompassing the whole of geographic Macedonia. It helped to redefine the so-called Macedonian question at home and in the rest of the Balkans and Europe. Thereafter people would view the problem no longer as Bulgarian or Greek or Serbian, as each of the neighbors claimed, but first and foremost as Macedonian.

The uprising and its disastrous end changed the national movement and long helped shape national identity. Those who expected the Bulgarians to offer armed support were faced with the reality that the real enemy was the neighboring Balkan nationalisms, including the Bulgarian, which claimed Macedonia and divided its people against each other. The events of 1903 and their aftermath even more profoundly affected the Macedono-Bulgarians, particularly the right-wingers who tended to be extremely pro-Bulgaria and expected Bulgaria to protect Macedonian interests. The Macedono-Bulgarian crisis spurred infighting and assassinations within the VMRO. Macedonians had to acknowledge that the interests of Bulgarianism and Macedonianism were divergent. It became obvious that Macedono-Bulgarians would have to choose between the two nationalisms, which had become irreconcilably contradictory; they could not be Macedonians and Bulgarians. This predicament helped split the VMRO between its Macedonian left and its pro-Bulgarian right—a divide that had existed since 1893. The post-Ilinden crisis launched the prolonged and agonizing end of Macedono-Bulgarianism. This divide was very evident in Zelenic as it would force many families to eventually move to Bulgaria after the Balkan Wars of 1912-13.

The Men of Zelenich and the Ilinden Uprising

The inhabitants of Zelenich played a big part in becoming involved in IMRO by planning and participating in the eventual revolt of 1903 and there after. The following personalities were involved (in some way or another) with the uprising against the Turks, Greeks and Bulgarians after 1903.

| Argir Dimitrov | Kocho Tsonkov |

| Vasil Kostov | Lazar Bitsanov |

| Dimitar Vasilev | Metodi Kotorchev |

| Simitar Mitsarov | Petar Stoyanov |

| Ivan Popdimitrov | Stefan Dimitrov |

| Ilia Yanev | Stefan Nikolov |

| Kire Mitov | Foti Kirchev |

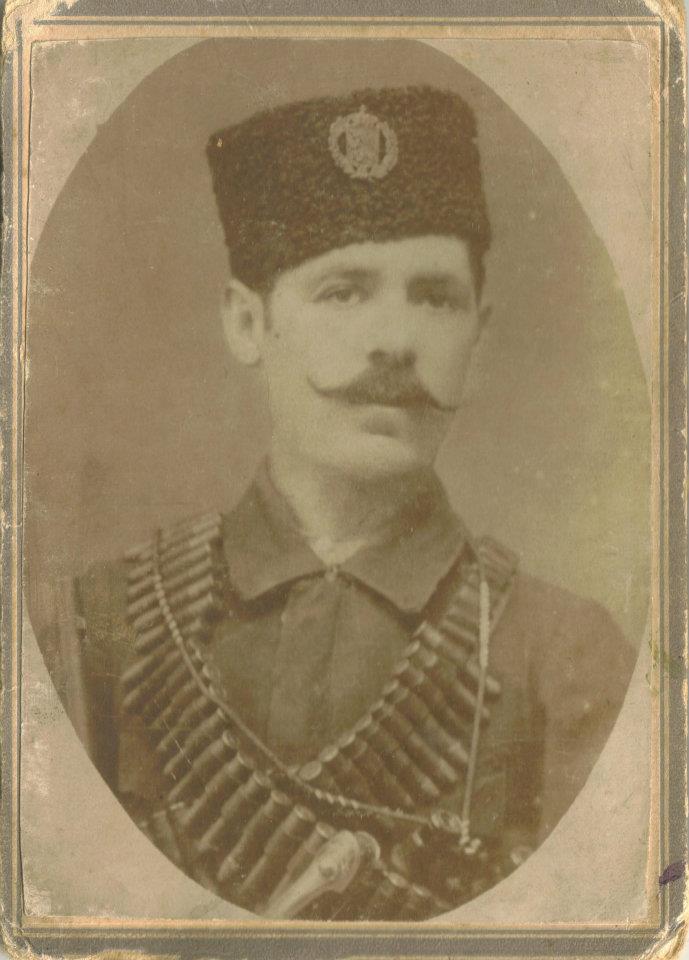

Kocho Tsongata and Foti Kirchev

Foti Kirchev with his family

Foti (Fote) Nikolov Kirchev was a Macedonian revolutionary, activist of the Internal Macedonian-Edirne Revolutionary Organization. Foti Kirchev was born on March 20, 1875 in Zelenić, then in the Ottoman Empire. From 1900 to 1902 he worked as a milkman in Constantinople. He joined IMRO and returned to Zelenić in 1902. In the spring of 1903, he was tasked with killing the pro-Greek (Macedonian) andarty captain Vangel Georgiev, but managed to eliminate only the pro-Greek (Macedonian) mayor of Strebreno (Asprogia). He became a Chetnik under Georgi Papanchev and took part in the battle on May 1. With 8 other rebels Kirchev then joined the detachment of Alexander Turundzhev as the remaning rebels joined Nikola Andreev in Mokreni.

On July 12, the united detachments of Nikola Andreev and Alexander Turundzhev were besieged after a betrayal in Gorno Kotori by the detachment of Vangel Georgiev and parts of the Lerin garrison. After an 8-hour battle, Kirchev was wounded in the leg and captured by the Turks. He was imprisoned in Bitola, tortured and sentenced to 101 years in chains and sent to Diyarbakir. He would later escape settle in Bulgaria. His wife Krasta Hristova Tsandileva was also from Zelenich. They had two children – Nikola and Vasilka. He died on January 31, 1956 in Sofia.

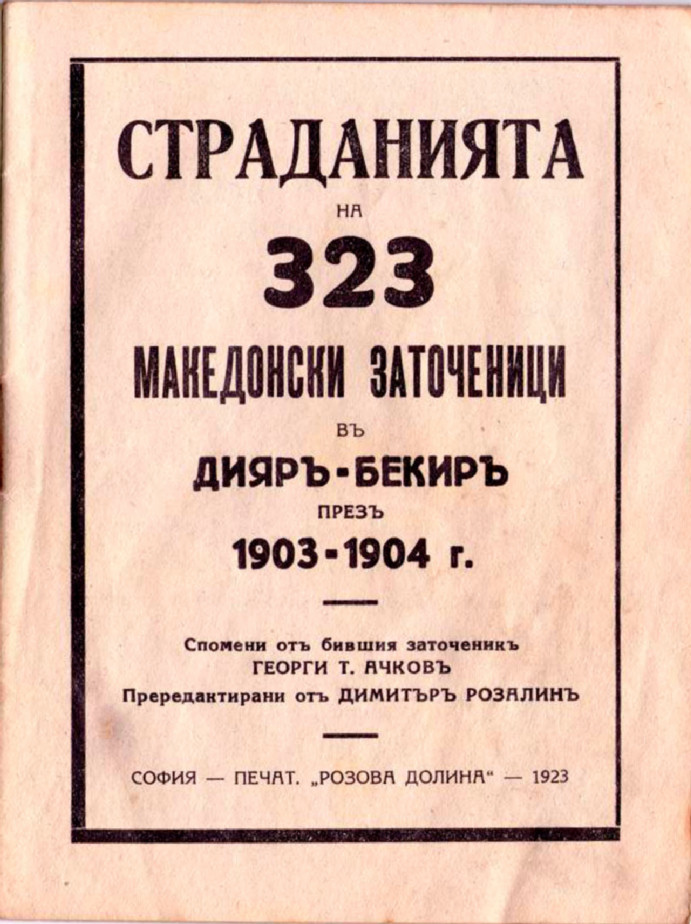

Foti Nikolov Kirchev was one of 323 Macedonian exiles that were sent on a torturous treck to Diyarbekir. Here is that story as told by Georgi Achkov from Prilep. The story was first published in 1923 (Sofia) and recently in 2019 at: https://off.net.mk/lokalno/razno/golgotata-na-323-makedonski-zarobenici by Blaze Minevski. Here is the English translation:

Titled: Golgotha of 323 Macedonian Captives

Golgotha, (Aramaic: “Skull”) also called Calvary, (from Latin calva: “bald head” or “skull”), skull-shaped hill in ancient Jerusalem, the site of Jesus’ crucifixion. It is referred to in all four Gospels (Matthew 27:33, Mark 15:22, Luke 23:33, and John 19:17 – For the 323 Macedonians, their “Golgatha” (their walk to Diyar-Bekir) was viewed similaraly as Jesus’ crusifixtion walk to the skull-shaped hill in ancient Jerusalem

Twenty years after returning from captivity during the Ilinden Uprising, Georgi Achkov from Prilep, one of the 323 Macedonians driven into captivity in Diyar-Bekir, mustered the strength to remember the horrors he endured in 1903-1904 when on the way to the prison in Mala Asia (Minor) were killed or died of torture, half of the Macedonians were sentenced to one hundred and one years.

After being arrested as a group that planned to join the squads preparing for the Ilinden uprising, Georgi Achkov, together with twenty other Prilep residents, was tortured for several days in the Prilep prison, and then transferred to the Hasta-Khane hospital in Bitola. While recovering from his wounds he met “Foti Nikolov Kirchev” from the village of Zeleniche Lerinsko. While he was in prison in his hometown, he heard that Hristo Oklev’s squad, the squad he and several others planned to join, had been defeated, that is, the “Duke” and three Chetniks had been killed.

In Bitola, before we were brought before the court, we were imprisoned in the so-called Basma-an, and then by the court’s decision we were transferred to the department for political criminals Katil-an to serve the sentence of life imprisonment. It was on those days that the Russian consul Aleksandar Rostokovsky was murdered, so the irritation of the Turkish population in the city was great, in fact we were waiting every moment for the mob to enter the prison and all be slaughtered. However, European pressure was great and the mob was prevented from entering the prison. In the meantime, in Katil-an I saw that my fellow citizen Vladimir Milchinov was also imprisoned, who was dressed in debar clothes, and in prison was under a different name. A month later, my mother came to visit me, and then she told me that my father was met on the road to the village of Senokos, beaten to death by two Turkish soldiers, and died of his injuries three days later.

Chained on the road to Thessaloniki

All those who were imprisoned in Katil-an on September 8, 1903, because they could not walk due to the beatings or because they were shackled on their legs, were transferred to the railway station in Bitola in Arab cars. From the Bitola prison alone, 62 Macedonian prisoners were piled into one of the freight wagons. When they reached the village of Voden, some of the prisoners tried to escape, but were caught, beaten, chained to each other and returned to the wagons. In the Thessaloniki railway station, they were brought in line to the district administration, and on the way they were whipped and beaten without ceasing.

In that Thessaloniki torture, Simo Trajkov from Kichevsko was stabbed with a bayonet, who was taken to the Thessaloniki military hospital, where he died ten days later. He was the first victim of the 323 exiles who arrived in Thessaloniki. For three days we lay in the Thessaloniki prison on the ground, without bread or water. On the fourth day, chained in heavy shackles, we set out for the port of Thessaloniki. When we were counted, it was found that two of the prisoners had escaped. We were transferred with boats to the steamboat and literally thrown down a small opening below the deck, and piled up in the part where the engines were. While we were pushing the hatch, the captain of the boat, a Greek by nationality, repeated several times that none of us would reach the shore alive. Then the hood was lowered. I remember that Dimitar Mirchev was among the prisoners. They landed him on the island of Mytilene.

Before he was called on deck he gave us 10 Napoleons to divide between us, among the 22 prisoners in the group. Anyway, after some time we arrived in Smyrna where we were quartered in the city barracks. As we walked to the barracks, we were spat at and beaten by the Turkish and Greek population that had come out into the street. Then Nedelko Atanasov from the village of Godech, Bitola, died from the beating. We stayed in the barracks in Smyrna for four days, waiting for the new prisoners to arrive in the city. The next day we were all loaded together on a new steamer. The captain was again a Greek with an unprecedented hatred for the Macedonians, which he did not hide from us. By his orders we dared not even open the hatch of the lower deck, nor did we dare to think of asking to go out for need. Inside, in that space, below, we had to defecate. It could not be endured, so on the ninth or tenth day we knocked it out of the hatch, went out on deck and somehow managed to stay in the open. The following day, the prisoner Josif Kondov and a dozen others were left on the island of Rhodes; they left a large group of Thessalonica prisoners in Podrum-kale, and all of us from the Bitola district were taken to the port of Alexandretta or Skendereno, that is, to the prison there, where four blacksmiths took the shackles from our feet, but did not tie them with chains, neck to neck , eight people each.

A group of Diyar-Bekir exiles in 1903-1904.

1) Mikhail Bogatinov, born from the city of Prilep

† 2) Nikola Belagushov, born from the city of Prilep

3) Candle. Ivan, born from the village of Jupa, Kichevsko

4) Candle. Duco, born from the village of Debartsa, Kichevsko

5) Grigoru Krastev, born from the city of Prilep

6) Mice Nikolovu, born from the village of Eshki-su, Lerinsko

7) Anastas Yajcharovu, education, born from the city of Ohrid

† 8) Boris Karakashev, b. from the city of Prilep

9) Georgi T. Achkovu, born from the city of Prilep

† 10) Pane Nikolovu, b. from the village of Gopes, Bitola

11) Nicho Filipovu, born from the city of Prilep

†Indicates those that did not make it back to Macedonia

All this was completed in two hours, and immediately after that an order came to go to the village of Ashley-bahce, which was 12 kilometers away from Alexandretta. Popat Mitso Kiritsov from the village of Gopesh, Bitola region, due to the tightening of the chain on his neck, began to bleed profusely and died in the middle of the road. He was left as carrion to the eagles. Only two hundred meters away, in a group where I was, Pancho Manev from Neret, Kostursko, fell half dead. However, they did not free him from the chain, so the rest of us seven had to carry him in our arms for about a kilometer, until one of the entourage killed him. They took him off the chain and threw him in the ditch next to the road. Before we entered the village, Ane Grozdev from Svinishta, Bitolsko, and Filip Bozhinov from Chumovo, Prilepsko were stabbed with bayonets of the army because they could not walk. We spent the night hungry, because bread had to be given to us only in the next village, in Hamam

Kurds were beasts of a people!

The next morning, somewhere halfway, a certain Bekir Pasha met them, who, after seeing that they were chained neck to neck, ordered the chains to be taken off, saying that if Europe found out, they would think that the Turks were barbarians. In front of him, they removed the chains from their necks and the ropes from their hands, and so it remained until the end of the path, until the end of their “Golgotha”. From Hamam-Koy, writes Achkov, we continued to the city of Aleppo, 30 kilometers away. A long and hard road. The soldiers who accompanied them took horses, and the prisoners had to walk side by side with the horses and even run in some places.

We could only follow them at that pace for one kilometer. Then we started to fall one by one. Anyone who fell would get a bayonet in the chest. But, in spite of that, we could not reach the city the same day, so ten kilometers before the city we slept in an open space, and the next day at dawn we continued towards the city. One kilometer before we entered Aleppo, we stopped at a madrasa where they ordered us to wash, clean our clothes, every trace of blood on the body and the clothes to be wiped off so that when we enter the city, it will not be seen that we are tortured. In Halep, we did not meet a very curious audience, among whom there were faces who looked like they were not sorry, but there were also Turks and Arabs who cursed and spat at us. On the third day we continued to the city of Urf, but we were now accompanied by Kurds, the most bloodthirsty people imaginable. They were dressed in thick shirts covered with a gray rug, belted with a belt, with bare legs, and on their heads they wore 12 colorful scarves, wrapped like turbans. Each of them carried a scimitar, two revolvers and a rifle. Each one of them looked like a wild beast capable of tearing you apart in an instant.

According to the shocking testimony of Achkov, recorded only 19 years after the “calvary”Golgotha” he experienced as a Macedonian exile in Asia Minor, as soon as they left the city, the Kurds took out their scimitars, took five prisoners, took them down to a pit and slaughtered them senselessly in front of everyone else. Then the journey continued for another six days and nights, during which time another 21 Macedonians were slaughtered with a Kurdish scimitar. At midnight on the seventh day, they entered the city of Urf, exhausted and beaten, locked in a cowshed that had been emptied of cattle an hour or two before. They lay in the cowshed all day and night without bread or water. When they got up, they saw that Mile Naumov from the village of Vranche, Prilepsko, had died lying in the mud between them. The city of Urf is in the middle of Kurdistan; Here, in Urf, in the monastery of Saint Naum, 1,500 Armenians were slaughtered during the Armenian Uprising. The Macedonian exiles stayed in Urf for three days, and then continued to the city of Berejik, traveling 12 hours a day, led by Kurds on horses. Tired, beaten and hungry, the horses had to follow them, because if they stopped even a little, the Kurds would immediately take out their scythes and start slaughtering them. Anyone who stayed behind, the Kurds immediately butchered him mercilessly. After five days they arrived in Beredzik. On the way, four died of shock, and seven were slaughtered by the Kurds because they could not keep up with the pace they forced them to ride on the horses. One of the slaughtered was Naumche Grozdanov from the village of Vranche, Prilep region.

A priest dragged by his beard tied to a horse’s tail!

We stayed in Beredzik for three days. On the third day we set off for Mimish-khan, two hundred kilometers away from Berejik. The city’s Kurdish militia gaveus kicks and threw stones, and when we left the city, the Kurdish soldiers continued to have fun, to pour their bloodthirsty fury on us. Two of them tied the hands of the priest Bilbil Chuturov, put a rope around his neck and tied him to the tail of an Arab horse. The rider pulled him with a horse, the priest ran two or three hundred paces, fainted and fell, and the horse dragged him for who knows how many paces at a gallop. Although he was dead and all mangled from the drag, the Kurds cut off his beard along with the skin and tied it to the tail of a horse. Immediately afterwards, the Kurds beat up Galab Mitrev from the village of Brzhdani, Kichevsko, cut off his ears and flattened his head with a stone. Of course, the path continued as if nothing had happened; after five days we reached Mishmish-khan. We lost another nine along the way; a line of five men, because they had doubled up a little to walk as needed, was shot, and four others were pierced with a bayonet. We stay in Mishmish Khan for one day, and then we set off for the town of Suverik, about 100 kilometers away. We traveled for two days and two nights, and during that time three more of our comrades were stoned to death by the local population.

With pains, with our last strength, finally, on November 10, 1903, we reached Suverik, the last point before our last station, before Diyar Bekir. By order of the Diyarbekir authorities, we were kept in Suwarik for two days, and on the third day, two of us tied with ropes, one part chained neck to neck, we left the prison in Suwarik, and a number of soldiers, built in two lines, hit us with the bayonets telling us where they will go. From the wounds they received from the bayonets, 16 people died on the spot, and 19 people remained in agony, and it wasn’t until a month later that we found out that they had been beaten by the crowd gathered in front of the prison. Apart from them, another 33 of us were lightly stabbed, but we had to continue walking towards Diyarbekir covered in blood. After six days of travel, we somehow reached Diyarbekir. We stood in front of the fortress door for an hour. Here we were sprinkled with water in which dead snakes had been standing for more than 10 days. Later we found out that it was some kind of belief, i.e. the water was supposed to protect the domestic Muslim population from infection, from our cow diseases. Then we passed through the city and were locked up in a prison called Hasan Pasha Khan. The seventy-day our “Golgatha” ended, and ten days after arriving in Diyar-bekir we obtained permission to go out into the prison yard for the first time. The Armenians, who were about 15,000 in the city, collected clothes and brought them to the gate.

The American Benevolent Society provided us with straws so that we would not sleep on the stone slabs in the prison. The city of Diyarbekir is surrounded by a stone wall eight meters high, three meters thick, with four gates, which are opened by the guard in the morning and closed by the same guard in the evening. Whoever is late to enter must spend the night outside the walls. And outside, everyone has the right to kill you like a dog. The town had about 28,000 inhabitants, and most of them were Armenians, but there were also Kurds and a few houses of Greeks. Life for those who lived there was very cheap: 100 eggs were sold for five groshis, milk for 10 paise, bread for 7 paise and fruit and vegetables for 5-6 paise. Bostanot had it in abundance. A watermelon weighed from 70 to 100 okas.

According to Georgi Achkov, the journey from Bitola to Diyarbekir lasted 70 days. 323 people left Bitola, and 121 people died by the time they arrived in Diyarbekir; 42 of them were slaughtered and 48 stabbed. The rest died from “effusion” in the brain, from fatigue, wounds, hunger and other tortures. Seven months later, on April 10, 1904, the prisoners received the happy news that amnesty was granted to all political prisoners, that they were released. On April 14, they leave for Macedonia. After 54 days of travel, the surviving 202 prisoners reached Macedonia and one of them was Foti Nikolov Kirchev from Zelenić.

Kocho Tsonkata was born in 1866 in Zelenich. For many years he led a detachment operating in his native Lerin region. In 1901 he was arrested during the Thessaloniki affair, sentenced to death on March 14, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and he was sent into exile. He was amnestied at the beginning of 1903 and during the Ilinden Uprising he was the central Voivode in the Lerin region. 250 people from the villages of Trsje, Armenia, Gorno Nevoljani, Nered, Lagen and Krapeshino rose up in his area. After the pogrom of the uprising he fled to Bulgaria. He returned with a detachment to the Lerin region in place of Nikola Mokrenski in the spring of 1905 and fought battles with the detachments of the Greek armed propaganda that appeared in Macedonia. He was killed in a hut above the village of Trsje in December 1906.

Stefan Dimitrov received his primary education in his native Zelenich, and finished high school in Plovdiv, where he became friends with Stefan Nikolov Kalfata. He studied mathematics at the University of Sofia, but in 1900 he left and became a teacher in the Kukush three-grade school. He joined the Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.

He was arrested by the Turkish authorities in May 1901 during the Thessaloniki affair. He was sentenced to 7 years in prison in Podrum Kale, but was amnestied in 1903 after the Ilinden Uprising. From the spring of 1904 to the spring of 1905, Dimitrov worked at reviving the revolutionary activity that had declined after Ilinden. Not only did Macedonians have to battle the Turks, Greeks and Bulgarians but now they were also fighting the Serbians who, increased their activities in Macedonia.

Stefan Dimitrov died on May 5, 1905 over the village of Oreshe after a surprise attack by the pro-Serbian Macedonian duke Jovan Babunski. Stefan Dimitrov is mentioned in the Chetnik song “I listen from where the sound is coming,” in which the fight between the pro-Serbian Macedonian Jovan Babunski and Stefan Dimitrov is sung:

“A Serbian trumpet sounded in that village of Drenovo. Get ready, get ready, Chetniks, A strong struggle will awaken. He goes forward in front of the fourth Jovan Babunski Vojvoda, For them he goes in front of the fourth Vasil Veleski Vojvoda. Jovan Babunski shouted: Hold the village below, hold the village below, it’s Stevan Dimitrov! Jovan Babunski shouted: – Surrender, Stefan! I do not surrender to you, I am the Duke of Vardar! “

Lazar Dimitrov Bitsarov

Lazar Dimirov Bitsarov enters the IMRO in 1899 and he becomes chairman of the revolutionary committee in Zelenich together with Stoyaneto. He joined a group for the supply of weapons together with Pandil Shishkov, Dine Abduramanov and Stefan Nastev, and later of the district revolutionary committee in Lerin (Florina). In 1905 he was sentenced to 15 years in prison. He was amnestied after the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 and then participated in the unifying congress of the Macedonian emigration in Bulgaria in January 1923.

Stefan Nikolov Kalfa was born in 1862. He settled in Bulgaria and was among the founders of the Macedonian Society in Plovdiv in 1895. He was sent as a Voivode of the IMRO in Aegean Sea in Thrace even before the Ilinden Uprising. In 1904 he was a member of the Veles Voivode Stefan Dimitrov. He remained there until the death of Dimitrov, and then was sent as an illegal to the Lerin region. During the Balkan War, Stefan Nikolov was again a Voivode and operated in Aegea Sea in Thrace in the vanguard of the Bulgarian army. On January 27, 1935, after a long illness, Stefan Kalfa died in Haskovo at the age of 73. His service was held on January 29 in the church of St. Demetrius.

Pando Mechkarov joined the IMRO in 1899 and became chairman of the revolutionary committee in his native village. He took part in the Ilinden Uprising in the summer of 1903 as the leader of the Prekopan detachment. He was killed in 1904 by the Greek Andartes during the attack on the village of Zeleniche, which became known as the Bloody Wedding of Zelenic.

Petar Stoyanov participated as a volunteer in the Serbo-Turkish War in the brigade of General Mikhail Chernyaev. After the war he left for Russia. After the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War he was a volunteer in the Bulgarian militia and on April 27, 1877 he was enlisted in the 1st Volunteer Company, 2nd Company. He was dismissed as a corporal on June 28, 1878. After the war he settled in Kustendil, which became part of the newly established Principality of Bulgaria. He worked as a bartender and died in Kustendil on July 16, 1913.

Sources:

A.TH.R. (2014, January 4). Σκλήθρο – (Ζέλενιτσ*)... ΠΕΡΙΣΚΟΠΙΟ. https://eperiskopio.blogspot.com/2014/01/blog-post_4.html

Barker, E. (1950). Macedonia. Its place in Balkan power politics. Greenwood Press.

Brailsford, Henry N. (1906). Macedonia: its races and their future.

Brooks, J. (2015). The Education Race for Macedonia, 1878—1903. Journal of Modern Hellenism, 31, 23-58.

Cheta of IMARO voivoda Stefan Dimitrov [Photograph]. (1905). Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7b/Stefan_Dimitrov_Cheta_IMARO.JPG

Dakin, D. (1966). The Greek struggle in Macedonia, 1897-1913. Institute for Balkan Studies.

Dimitras, E. P. (2000). Writing and Rewriting History in the Context of Balkan Nationalisms. Southeast European Politics, 1(1), 41-59.

Eötvös University, Faculty of Informatics, Institute of Cartography and Geoinformatics. (1900). Monastir-Bitola Region. lazarus.elte.hu. http://lazarus.elte.hu/hun/digkonyv/topo/200e/39-41.jpg

IMARO united chetas at Skopie congress, 1905 – Efrem Chuckov, Mishe Razvigorov, Atanas Babata, Stefan Dimitrov, Krustio Bulgarita and others [Photograph]. (1903). wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ea/IMRO_bands_at_the_Skopje_assembly%2C_1905.jpg

Gingeras, Ryan. (September-December 2008). Between the Cracks: Macedonia and the ‘Mental Map’ of Europe. Source: Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes. Vol. 50, No. ¾, pp. 341-358 Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40871305

Gounaris, B. C. (2005). Preachers of god and martyrs of the nation. The politics of murder in ottoman Macedonia in the early twentieth century. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/29978518

Kandi. (2017, July 17). Macedonian national revolutionary movement in 1903 [Map]. Wikipedia.org. https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/%CE%95%CE%BE%CE%AD%CE%B3%CE%B5%CF%81%CF%83%CE%B7_%CF%84%CE%BF%CF%85_%CE%8A%CE%BB%CE%B9%CE%BD%CF%84%CE%B5%CE%BD#/media/%CE%91%CF%81%CF%87%CE%B5%CE%AF%CE%BF:Bulgarian_national_revolutionary_movement_in_Macedonia_and_East_Thrace_(1893-1912).png

Karakasidou, A. N. (2009). Fields of wheat, hills of blood: Passages to nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990. University of Chicago Press.

Karastoyanov, D. (1902). Participants of Miss Stone Affair [Photograph]. Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/38/Sandanski%26chernopeev.JPG

Le Petit Journal. (1903, July 26). A Macedonian Joan of Arc. Catherine Arnandouda, leader of a band of fighters against Ottoman Turkish rule [Journal Cover]. https://www.lookandlearn.com. https://www.lookandlearn.com/history-images/M500190/A-Macedonian-Joan-of-Arc

Lithoksou. (1998).. 2. Η Επανάσταση του Ίλιντεν. (n.d.). lithoksou.net |. https://www.lithoksou.net/p/2-i-epanastasi-toy-ilinten Μακεδονικός Αγώνας ή Ελληνικός Αντιμακεδονικός Αγώνας [1998] Ελληνικός αντιμακεδονικός αγώνας. Greek Anti-Macedonian Struggle

Lithoksou. (1998). Χάρτης της Δυτικής Μακεδονίας στα χρόνια του αντιμακεδονικού αγώνα [Map of Western Macedonia in the years of the anti-Macedonian struggle]. Lithoksou.net. http://www.lithoksou.net/p/xartis-tis-dytikis-makedonias-sta-xronia-toy-antimakedonikoy-agona

Lithoxoou, D. (2012). The Greek Anti-Macedonian struggle: Part I: From St. Ilija’s day to Zagorichani (1903-1905). Salient Publishing. Translated by Chris Popov, David Vitkov, George Vlahov

Ljorovski Vamvakovski, D., Dr.(2015, April 1). The Ilinden Uprising and the Kingdom of Greece: A Plan for the Taking Over of the Uprising and/or Provoking of a “Civil War” in Ottoman Macedonia. Macedonian Human Rights Review, (22).

Macedonia History. (2017, August 11). Macedonian revolutionaries collecting explosives for the Ilinden Uprising – 1903. Macedonia History. https://history-from-macedonia.blogspot.com/2017/08/macedonian-revolutionaries-collecting.html Illustration of the Macedonian Uprising printed in the french newspaper “Le Pelerin” 6th of September, 1903. Pettifer, J. (1999). The new Macedonian question. Springer.

Minevski, B. (2019, November 5). Голготата на 323 македонски заробеници. Golgotha of 323 Macedonian Captives. Off. https://off.net.mk/lokalno/razno/golgotata-na-323-makedonski-zarobenici

Popov, C. M. (n.d.). [Photograph]. Wikipedia Commons. https://bg.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9A%D0%BE%D1%87%D0%BE_%D0%A6%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2#/media/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:BASA-1932K-1-438-6.JPG

Postcard (1902) showing missioner Miss Ellen Stone [Photograph]. (1902). Wikimedia.org. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/89/Miss_stoun_case.jpg

Radovanovic, I. (2017, July 25). The debate between Goce Delcev and dame Gruev which preceded the Ilinden uprising. Macedonia History. https://history-from-macedonia.blogspot.com/2017/07/the-debate-between-goce-delcev-and-dame.html In the memoirs of Vojvoda (duke) Lazar Dimitrov, published in 1930, he remembers meeting Delcev and discussing the upcoming fight against the Ottomans.

Rosalina, D. (1923). Георги Ачковъ – Страданията на 323 македонски заточеници въ Дияръ-Бекиръ презъ 1903-1904 г. Книги за Македония. The Golgatha (sufferings) of 323 Macedonian exiles in Diyar-Bekir in 1903-1904 https://macedonia.kroraina.com/uchastnici/achkov_1923.htm

Rezano. (2010, January 2). Portrait of IMARO member Stefan Dimitrov from Zelenic [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stefan_Dimitrov_IMARO_Zeleniche.JPG

Rossos, A. (2013). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A history. Hoover Press.

Roshev: РОШЕВ, K. (2000). ВОЈВОДИТЕ НИЗ СОБИТИЈАТА И НАРОДНИТЕ ПЕСНИ ВО ЛЕРИНСКО И КОСТУРСКО. МАТИЦА МАКЕДОНСКА, Скопје.

Sherman, L. B., & Sherman, L. (1980). Fires on the mountain: The Macedonian revolutionary movement and the kidnapping of Ellen stone. Columbia University Press.

Stone, Miss Ellen [Photograph]. (2007, January 26). Wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miss_Stone_Affair#/media/File:Ellen_Maria_Stone.png

Templar, M. A. (2015, July 20). Ilinden: A story of the web and the harpoon. Academia.edu – Share research. https://www.academia.edu/14624185/Ilinden_A_Story_of_the_Web_and_the_Harpoon

Todoroff, Kosta. (Apr. 1928). The Macedonian Organization Yesterday and Today. Source: Foreign Affairs, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 473-482 Published by: Council on Foreign Relations Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20028628

Unknown Author. (2007, January 26). Зелениче – Уикипедия. Уикипедия. https://bg.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%97%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%87%D0%B5

Unknown Author. (n.d.). Portrait of IMARO Voivoda Kocho Tsonkata [Photograph]. Wikipedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2d/Kocho_conkata.JPG

Pre 1903

Unknown Author. (1904). Cheta of IMARO voivoda Stefan Dimitrov in Veles [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7b/Stefan_Dimitrov_Cheta_IMARO.JPG Almanach “Macedonia”, page 475

Unknown Author. (1919). Koco Tsongata [Photograph]. Wikipedia Commons. https://bg.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9A%D0%BE%D1%87%D0%BE_%D0%A6%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%BA%D0%BE%D0%B2#/media/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Kocho_Tsonkata.jpg

Unknown Author. (1920s). Family of Macedonian Revolutionary Foti Kirchev [Photograph]. Wikipedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/71/Foti_Kirchev_%26_family.gif

Unknown Author. (1923). Lazar Bitsanov [Photograph]. Wikipedia Commons. https://bg.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9B%D0%B0%D0%B7%D0%B0%D1%80_%D0%91%D0%B8%D1%86%D0%B0%D0%BD%D0%BE%D0%B2#/media/%D0%A4%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB:Lazar_Bitsanov.jpg