The Age of Revolutions

The end of the 18th century was marked by the influence of the liberal ideas of the French Revolution with the flourishing of romanticism, rationalism and enlightenment. This also appeared in Macedonia and especially Zelenic (Sklithro). The second half of the 19th century, a period of being deprived of statehood and a standardized language, common Macedonians exhibited their identity through the church. Even though the Ohrid Archiepiscopacy was abolished by the end of the 18th century, the Macedonians and those in Zelenic attempted to resurrect their church but were challenged first by the Greek Patriarchy, then by the Bulgarian Exarchate and to a lesser extent, by Serbian Orthodoxy.

In the 19th century, the great powers began to show interest in the Balkans. With the insurrection of the Greeks in 1821, Europe became philhellene, driven by romanticism. This interest, at first literary and romantic, turned into an historical and geopolitical argument, and became the basis of the ideology of Western colonization. To justify the superiority of their “white race” in their colonization work, the Westerners (especially the Germans) chose as ancestors the Hellenes of the cities, for classical culture, and the Macedonians for their conquests of the known world of antiquity, giving them the generic name of Greeks. It was in this sense that the Prussian Johann Gustav Droysen, concerned about the problems of German unification, reconstructed the history of Southern Balkan antiquity, which he later called “History of Hellenism”. and then confused the two. Instead of appropriately calling the Period subsequent to Alexander the Greats time the Macedonistic Period“, he opted for calling it “Hellenistic,” which in effect robbed the Greeks of their African roots.

It is “history making” which creates opportunities – through an invented past – to reinvent the present … (unknown)

In order to attain a picture/narrative of the century, as to how this influenced the village of Zelenic, one needs to explore the motivation and role played by the Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian clergy and churches, but also, how these newly formed states developed their own narrative by all claiming Macedonia and Macedonians under their own historiography.

A Contested Land & People

Macedonians lived in contested territory as Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs labelled them a Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs. respectively and in accordance with their own geopolitical designs. During the period from the 1820s to the 1860s, Russian Panslavists purposely interpreted the subjugation of Macedonia and Macedonians in the middle ages as a single people with Bulgarians in order to promote their geopolitical expansion into the Balkans. Russia saw it in her interest to encourage a Macedonian-Bulgarian union as it corresponded to her designs toward the Mediterranean Sea. As such, Russia set about the Bulgarisation of Macedonia. Although an alliance was formed under the common struggle against Greek ecclesiastical domination, Bulgarian nationalists hijacked the struggle for domination over Macedonia.

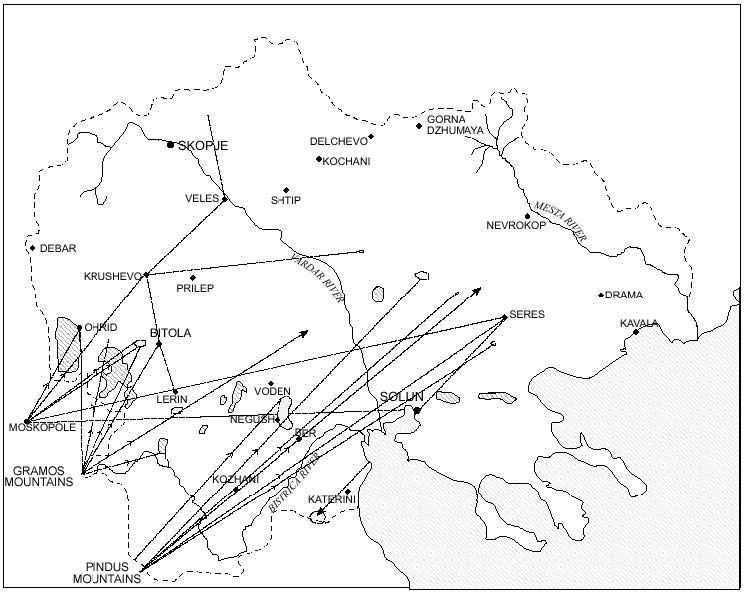

Between 1750 and 1850 successive waves of refugees settled in Macedonia. Vlahs inhabiting a line stretching south from Moskopole to the Gramos Mountains became victim to constant terror by Albanian Muslim bandits. They were Christians (Albanians and Vlachs) evicted from Epirus due to the continuous disturbances caused initially by the Albanian tribes and later on by the Ali pasha (Bashibouzuk) irregulars. In the course of a century a considerable number of new villages were established throughout Macedonia. This was the case for both Lehovo (Eleovo) and Nymphao (Neveska)

According to oral history, which can be supported by evidence of migrations to the region, both Lehovo (Eleovo) and Nymphao (Neveska) became populated by Albanian Christians (Arvanites-Arnaouti) and Vlachs (Wallahians). These two groups fled from the banditry perpetrated by the Muslim Albanian irregulars of Ali Pasha. The Christian Albanians came to the Zelenic valley to settle but, the villagers only allowed them to settle on the south-western slope of the Vicho mountains. The name Eleovo, actually derived from the word “left – levo” in the native Macedonia tongue. Ten (10) Christina families from present day Albania wanted land from Zelenic and they were given “Planina Golina” and “Bishkarnitsa.” Originally, Zelenic had “sinora” a bourder with the village of Mokrani (Variko) before the land was given to the Arnaouti (Albanians).

As for Neveska (Nymphao), the original inhabitants were Macedonians from the same settlement as people of Zelenic, in Sebaltsi. After the rebellions of the Greeks and Serbs, Albania Muslims began a campaign of banditry and forced the Vlachs from Moskopole (present day Voskopoje, Albania) and the Hrupishta (Argos Orestiko) area to settle on the mountain tops of the region. There is an interesting story about a “Baba Russa” who had to be married off to a Christian man from Neveska. As the story goes, “Baba Russa” was a very beautiful blond girl who was being stocked by a Muslim in Zelenic. The family tattooed a cross on the young girl’s forehead and married her to a Christian in Neveska. From that time on, their developed an understanding between Christian and Muslim elders and that they would not allow (discourage) a union between the two religious groups.

The rebellions to the north and south of the Macedonia created a period of anarchy. The inhabitants of Western Macedonia continued to suffer at the hands of Ali Pasha until 1822 when he was killed. This did not stop Moslem Albanian irregulars from oppressing the western parts of Macedonia (Hripista, Florina, Siatista, Kastoria, Naousa, Kleisoura, Monastir, Korytsa, Prilep and Ohrid). The village of Zelenic was left untouched and this may be due to the good relations between the Muslims and Christians in the village.

The economic and cultural conditions in the Balkans at the end of the eighteenth century advanced at a snail’s pace for those who lived in the rural areas. Trade had brought more opportunities for both Christians and Muslims who lived in cities but the social conditions of those who lived in villages were at a standstill. The age of revolutions brought something previously unknown to the Balkans. From being loyal to their relatives and clan, one was now supposed to become loyal to an invisible state and nation.

By 1830 things began to change

The Protocol of London in 1830 recognized the formation of the independent Greek state. A national ideology emerged with the goal of re-contextualizing the Rum-millet (Eastern Orthodox Christian populations) cultures of the Ottoman Empire into the framework of the nation-state. The predominance of the Christian Orthodox dogma and the Greek language as both the medium of communication for Church, administration and commerce in a significant part of the Ottoman Empire especially in Macedonia began in 1767 with the abolition of the Macedonian Archbishopric of Ohrid.

Macedonian towns/villages began repudiating the episcope sent from the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul. The first being in 1823, thus promoting service in their own liturgical language. Therefore, the Macedonian people under the guide of its own priests, appointed directly by the people, took charge in saving their own Macedonian Apostolic Church.

Pre-1767 the political, social and cultural aspects of the Rum-millet constituted an important part of Ottoman society and accommodated the various groups whose ethnic, linguistic or local prevented their inclusion or even absorption into one homogeneous religious identity. Cataclysmic changes were soon to follow in the nineteenth century. The nature of the Rum-millet after 1776 and the forced inclusion of the Greek language onto all the orthodox faiths coupled with the emergence of the Greek state after 1830 provided a template for a new social and cultural geography of Greekness.

Thus, this Greek state begins to reform the Romeic cultures of the Balkans according to the principles of a national ideology, the territorial expansion of the country and the emergence of the issue of Greekness. In order to preserve the Macedonian Apostolic Church locals openly repudiated agents of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. First, they banned Macedonic liturgy and worship in Macedonian cities where they were appointed. Second, the foreign bishops used their authority to collect the church taxes, which were then used for political purposes.

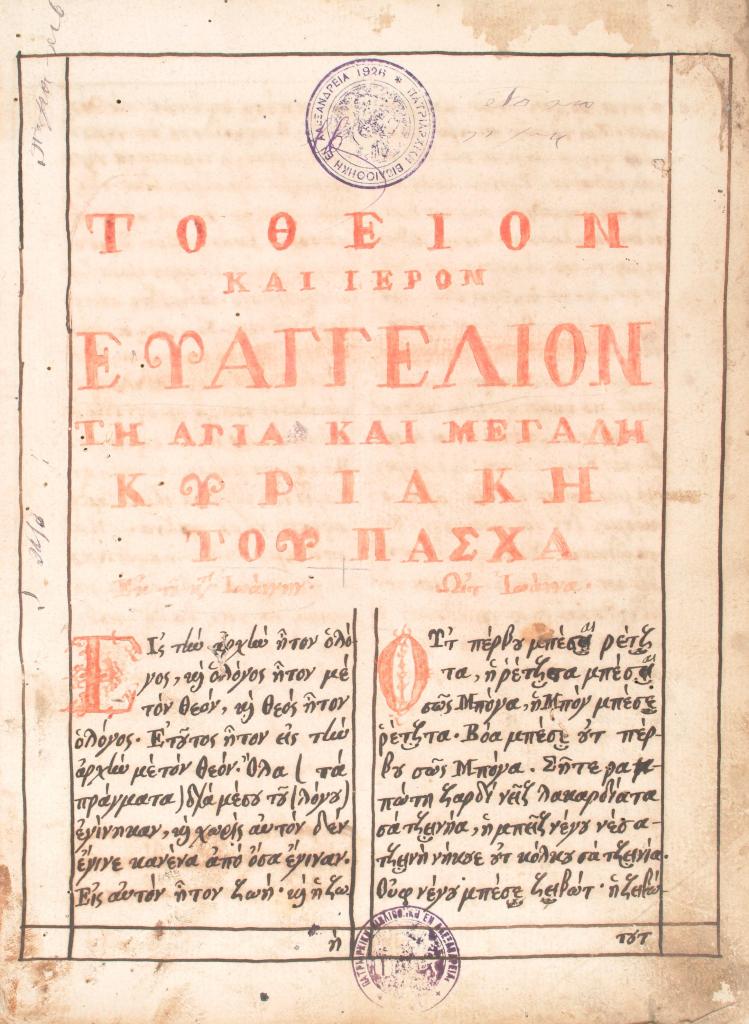

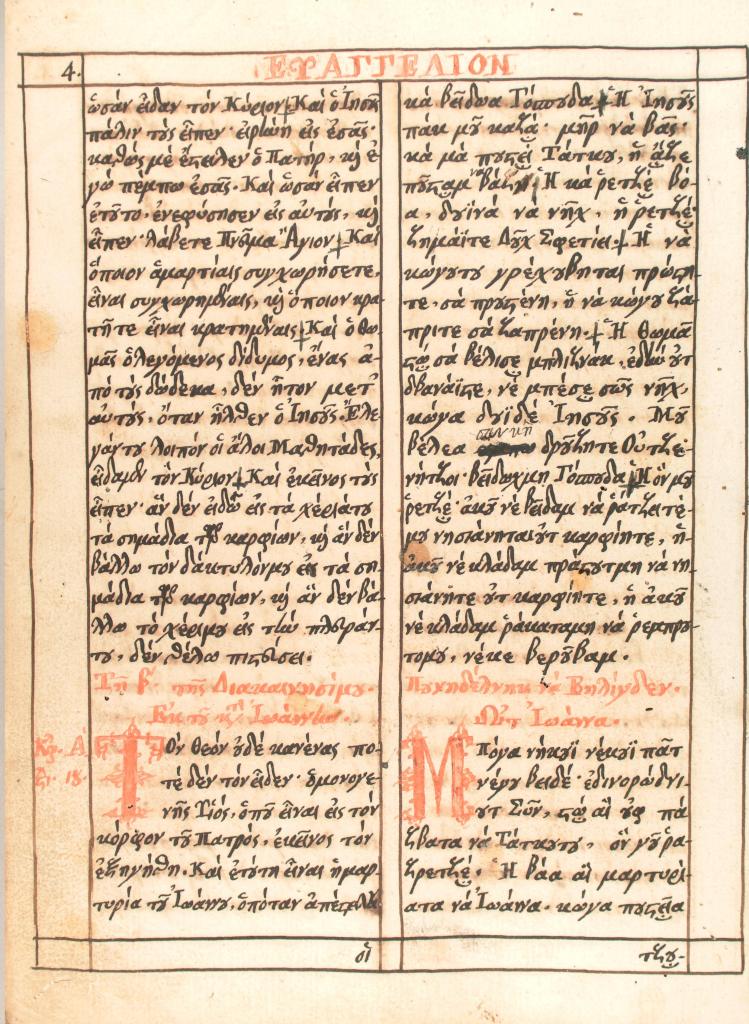

The Macedonian people under the guide of its own priests, appointed directly by the people, saved their very own Macedonian Apostolic Church from total disaster. Holy artifacts and books in Old Church Slavonic (Macedonic) were meticulously copied and preserved for future generations by common people. This was also the case in Sklithro-Zelenic right up to the 20th century, as the leaders of the prominent families in the village chose their first official mayor with the rebuilding of their old church St. Christopher, renamed as St. Demetrius and the construction of a second, St. George is built on land donated by the Siklev family. No other village or even town in the area had two Macedonian churches. Zelenic even had a third, the chapel St. Friday (Sv, Petka – Agia Paraskevi) on the northern mountainside. Deacons and priests chosen by these Church Committees continued the holy service in Macedonic (Old Church Slavonic) language and rite. They transcribed, lectured, and transmitted the Holy Macedonic Gospels and Liturgy across the Macedonian peninsula despite all the forms of mistreatment and persecution used by the Greek Patriarch.

In the rural area of Macedonia, the local churches continued to provide liturgical service using Old Church Macedonic but, the cities provided protection to the Greek clergy as a portion of the taxes they collected went to their Turkish protectors due to the sanctioning of the Ecumenical (Greek) Partriarchate as the sole provider of the Eastern Orthodox faith to all Christians in the Balkans. The term “Greek Orthodox” encompassed all Christians in the Rum Millet of the Balkans which only referred to and joined together all those of the same Orthodox religion and had nothing to do with “ethnos or genos” – ethnicity/birth or race. Even today, in the 21st century the Ecumenical Patriarch of Istanbul (Constantinople) is referred to as the Greek Patriarch when in fact, the term “Greek” no longer applies to the many different Orthodox churches. In trying to create a homogeneous Greek religious identity in 1767, the Patriarch instead, sparked the push for separate and independent ethnic churches throughout the Balkans.

Orthodox Commonwealth

The role of the Orthodox Church in the formation of ethno-religious identities and in its development into national identities during the nineteenth century is visible in the cases of the Serbs, Romans/Greeks, Vlachs/Romanians, Bulgarians and Macedonians. Three of the five Balkan national movements fully developed their respective national identities through their own ethnic states, the fourth, the Bulgarian developed partially through its ethnic state and the fifth, Macedonian not only had to battle their Ottoman oppressors, but also had to battle all the other Balkan movements.

The collapse of the Orthodox Commonwealth began in 1831 with the Orthodox church in Serbia, followed by the Kingdom of Greece which established a separate church in 1833. The church in Romania became independent from Constantinople in 1865 and the Bulgarian church (Exarchate) was established as a completely separate body in 1872. Thus between 1831 and 1872 Balkan Orthodox churches were fully “ethnified” and became promoters of their own national ideas. It is these four national ideas that attacked the forming of a separate Macedonian national church and idea. The name “Greek/Bulgarian” became a synonym for “Christian” and these labels were used to assimilate Macedonians into the Greek or Bulgarian camp.

You were called Greek because you followed the Eastern “Greek” Orthodox Patriarchist Church

OR

You were called Bulgarian because you followed the Eastern Orthodox “Bulgarian” Exarchist Church

The National Awakening of the Macedonians in the 19th century

By the 1860s a Macedonian renaissance started to take place as it was instigated by a small intelligentsia, which worked against Greek, Serbian and Bulgarian infiltration. The rise of a Macedonian national consciousness along with attempts to form a Macedonian literary language, or at least a literary language based to a large extent on Macedonian dialects, was not only discouraged but also attacked at this time.

During their battles to free themselves from their Ottoman oppressors, Serbs, Greeks, Romanians and Bulgarians were supported by Macedonians in each of these revolts for freedom. But the formation of a Macedonian national idea was attacked, first with the use of religion (priests/bishops), then education (teachers), with paramilitary insurgents (terrorists), and finally with national armies. It is no wonder that Macedonians (especially) common uneducated village peasants were in a easy prey for indoctrination and some became radicalized to promoted foreign agendas. This is evident as foreign travellers would ask villagers of their ethnicity, and the answer would change with the prevailing geopolitical climate of the time. Their main goal was survival as their faith, ethnicity, and national identity was threatened, bought and sold by the groups vying for their ownership. This was very evident in view of Goce Delcev (Macedonian National Revolutionary Hero) who was ahead of his time in his proverbial sentence: “I understand the world solely as a field for cultural competition among nations”. It is this competition that muddled and prevented the true narrative of the people of Macedonia to flourish as did the historiography of each of the newly formed states of Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania.

Two Battle Fronts Nationalism & Language

During the first half of the nineteenth century the two major problems that existed were Hellenization and the distinction between the Bulgarian/Macedonian identity. The main problem of this period for the Christian South Slavs (Macedonians) living in Ottoman territory was that of combating of Hellenization, and Bulgarization at the same time, while trying to preserve and protect their own Macedonian identity.

Even with this foreign competition in claiming ownership over Macedonia and Macedonians, there appeared a “National Awakening” that promoted a distinct Macedonian identity. The difference between the Macedonian “Awakening” and the ethno-national awakenings of the Serbs, Greeks, Romanians and Bulgarians, is that the later was influenced and supported by foreign interests who painted their own geopolitical and historical narratives (with a racist irredentist agenda) in supporting the “Great Ideas” of both Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria.

In Ottoman Macedonia, the national awakening of Macedonians was not adopted from outside but, was born from within the common people themselves. The oral traditions, folk songs, epics and poems of the people of Macedonia living under Ottoman rule, were used in liberating these enslaved people. Towards the second half of the 19th century, literacy and education flourished as Macedonians began taking ownership over claiming their identity through oral history, folk culture, songs, poetry, language and religion.

As more and more Macedonians began flocking to the newly independent/autonomous states of Greece, Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria, there grew a new intelligentsia, a Macedonian one which took on the ideals of the French Revolution of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity. It is this awakening which Serbia, Greece and especially Bulgaria took advantage of and adapted this awakening as their own by manipulating and then assimilating the Macedonian people through religion, language, nationalism and historiography.

Pure Macedonia

Macedonian, Turkish and Greek, was common among its Orthodox Macedonian speaking peoples. History, folklore, and archaeology was used to furnish arguments in order to prove the belonging of these regions to particular ethnic/national groups. Many Macedonian literary figures expressed their dissatisfaction with the use of the eastern dialect of Bulgarian in literature and textbooks. The national awakening introduced significant literary names, as Konstantin and Dimitar Miladinov, Rajko Zinzifov, Grigor Prlicev, Gjorgjija Pulevski, and others. In the 1860s, people in Salonika were saying they were neither Bulgarian, Greek, Serbian or Aromanian, but “pure Macedonian.”

This expression of nationalism was evident in the village of Zelenic that, by the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, land was not enough to support the village’s population. At that time, the men of Zelenic began emigrating to Istanbul and later to Rumania and Bulgaria, bringing back with them, not only the spoils of their hard labour, but also, the ideals of preserving their identity through liberty, freedom and their faith.

The mid-nineteenth century was the period of the Macedonian Revival. People all over Macedonia began to resist the policy of Hellenization imposed on them by the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople. “Zelenicheny” were no exception. Money sent back home by the emigrants and sojourners helped build 23 mills; a weekly farmers market and later in the century, two markets; various businesses, income by raising cattle, sheep, swine and goats; the production of silk, wool and linen; the building of three churches, a school; and so on.

The creation of a leading group of notables in Zelenic had developed between the wealthiest clans. Social stability in this agrarian society lead to social mobility due to a ruling elite that had access to trade and jobs in the urban centres. Many of these wealthier families that had businesses in Istanbul donated funds to help build St. Stephan Orthodox Church. Even though it is called a Bulgarian church, it was Macedonians from the Kostur (Kastoria) and Lerin (Florina) region that built this church. The majority of this so called Bulgarian community in Istanbul today have their roots in Western Macedonia and not Bulgaria as, after the formation of the Bulgarian Exarchist Church, all of the ethnic Bulgarians in Istanbul moved back to Bulgaria, leaving the Macedonians from Kostur and Lerin to hold the reins of this community in Turkey. Eventually, their choices determined, in a positive or in a negative way, their national preferences and eventually their future. But even to this day (2020), we have “so-called Bulgarians” identifying as Macedono-Bulgarians who still have connections with villages in Western Macedonia. If you can read Turkish, have a look at Georgi Kostandov’s book, İSTANBULLU BULGARLAR VE ESKI İSTANBUL (A contribution to the history of the Bulgarian community in Istanbul). The authors family came from Zagoricani (Basiliada) just below Prekopana (Perikopi).

1857 Wooden Church 1899 Cast Iron Church

The first attempts at a Macedonian literary language have their roots in the struggle against the Hellenizing policies of the Phanariot Patriarchate from the 1840s through the 1860s. It is during this time that we find the Macedonian national consciousness appearing in the village of Zelenic with the expansion of economic activities culminating with the building of three churches and a school.

St. Demetrius 1844

The first church in the village was called St. Christopher, but this church was destroyed by some fanatical Turks. It was only after many pleas to the Turkish governor in Bitola that the villagers were given permission to build a new church on the same site. In 1844 a new church was built and dedicated to Saint Demetrius. The site of St. Demetrius (originally, St. Christopher) is located by the cemetery. Beside this church today, there stands a 400-500-year-old oak tree that may be representative of an earlier pagan/Christian marker. It is believed that the original inhabitants of the village relocated their church to this site after Yoruk (Turkish) colonists came and confiscated the land below ‘Gradishta’ where the original church and village was located. The common practice of Muslim settlers was to convert Christian churches into mosques. A minaret stood at this location up until the early 1960’s, the location of the present-day kindergarten school. That was also the original site of the village from the 1390’s. The founders of Zelenic came from the now non-existent village of Seblatsi/Sebaltsi. After the settlers had cleared the land around the village Turkish colonists came and confiscated the land of the Macedonians. The Macedonians had to be content with the poorer land north of the village. Because the land to the north of the village was poorer, the residents had to supplement their income by raising cattle, sheep, swine and goats.

CLICK HERE FOR >>> PICTURES of ST. DEMETRIUS >>>

St. Friday (Agia Paraskeva – Sveta Petka)

The cult of Saint Parascheva (Sveta Petka in Macedonian – Agia Paraskevi in Greek) spread in the 14th century from Macedonia northwards before the Ottoman invasion. One can assume that Saint Friday may have been the patron saint of the first inhabitants that settled in the Sklithro-Zelenic area after leaving the Sebaltsi location by Lake Zazari after 1396.

Saint Paraskeva of the Balkans (Petka) for Orthodox Christians is known as the protector of women, the sick and the poor. Believers turn to prayer for help and safety from a disease and other life troubles. The cult of St. Petka has been cultivated for centuries in South East Europe. Near St. Petka temples one can often be find mineral springs – “Life Giving Spring” – that people drink from, believing that they will heal their wounds and protect them from diseases.

According to oral memory, there were two celebrations for St. Friday (Sv. Petka), first in April one week after Easter and the second in August. The Goddess of the pagans, Saint Petka’s healing energies are ascribed to holy wells and springs throughout Macedonia, and especially in the village of Sklithro-Zelenic. Many legends exist about the origins of the spring, whereupon the healing waters ushered forth from the earth also show a devotion to Christ.

As a weaver, Saint Petka in Macedonian lore has dominion over the women’s-only fibre arts of wool carding and thread spinning and weaving. On her feast day, however, village oral history stated that one must not engage in those activities lest she punish the household. It’s customary to offer the ritual food before her icon at the family altar–the same ritual food offered to the ancestral dead, which has one thinking Petka is a guardian of the female ancestral line known to pre-Christian Teutonic cultures. Women of the village were not allowed to do any housework other than cooking, the men were out on the fields tending to their crops.

The miracle of finding the image of the “Life Giving Spring – Saint Friday“

A second church (chapel) named Sv. Petka is on the middle of the slope “Prosilio” the mountainside called “Siniatsiko” below Neveska-Nymphaio. According to villagers, a lady had a dream of an icon buried in the mountainside below Neveska-Nymphao.

The story of finding the icon of “Life Giving Spring” begins in the period 1840-1870 when Efterpi, a resident of the village, saw the Virgin Mary in a vision. Efterpi’s mother after she got married could not have children for many years and begged the Virgin to give her one, even giving a promise to the Virgin that she dedicate her life to God. Her prayers were answered and after a few years Efterpi was born.

When she reached the age of marriage, Efterpi married in the neighboring village of Strebranoa (Asprogeia today), but the day after her wedding she returned to Zelenic (Sklithro) to her paternal home after she refused to sleep with her husband. Her parents considered it a shame that their daughter left her husband, with her father insisting on returning to her husband. But her mother, as she always remembered the promise she had made to the Virgin Mary, did not insist because she believed that it was God’s will.

A few years later, Efterpi sees the first vision: a very beautiful and sweet woman as she described, to ask her to visit her because everyone had forgotten her and she could no longer be alone! Efterpi, after confessing this vision to her mother, advised her not to say it anywhere because they would think she was crazy after she had previously divorced her husband. Efterpi obeyed, but for the second time she saw this female figure in a vision who complained that she did not go to find her, even indicating the place where she would find her.

Again, Efterpi did not go since her sister prevented her. However, the Virgin Mary appeared for the third time in Efterpi with the threat that if she did not go to find her, this time something very bad would happen to her. Efterpi, determined to go and while no one from her family followed her, took a Turkish boy aged 10-12 as an assistant and digging in the place indicated by the Virgin Mary through the visions, they found the image of the “Life Giving Spring of Saint Friday”, which at the same time began gushing holy water.

There she built a small chapel with stones and placed a small chandelier. From that day until the end of her life, Efterpi dedicated her life to the Virgin Mary, going daily to the chapel to light the candle she made herself. This miracle was learned in the whole surrounding area, with the result that many people arrived in Zelenic (Sklithro) to pray and be sanctified by the miraculous image.

In 1959, while Zelenic, now called Sklithro was still the capital of the area, the priest of the village, Dimitrios Papadimitriou, seeing the worship of the people, asked Dimitris Tsimeropoulos, who had a vineyard under the church, to give it to them so that they could build a bigger one. The god-fearing man without a second thought gave up his field and so the chapel of Agia Paraskevi (Sv. Petka) was enlarged where in the front part was placed the icon of Saint Friday, being a protector for all the inhabitants of Sklithro who continue to celebrate it twice.

CLICK HERE FOR >>> PICTURES OF ST. FRIDAY <<<

St. George

A third church, called St. George, it is located at the entrance of the village and was built in 1867 on land donated by the Siklev (Siklis) famiy. Accourding to oral history a terrible catastrophe broke out when the torrents of a storm came down the mountain which swept away St. Friday (Sv. Petka-Agia Paraskevi). When the flood subsided a little later and the waters receded, some Zelnicheni found an icon of St. George which had been swept away from St. Friday settling in the central part of the village. The place where the icon was found belonged to the Siklev (Siklis) family, which considered the finding of the icon a significant sign and thus granted the plot of land for the construction of the church in honour of St. George.

CLICK HERE FOR >>> PICTURES OF ST. GEORGE <<<

According to the old residents of the village, the first Macedono-Bulgarian school in Zelenic was opened by Dinkata in 1870, in the home of Georgi Jouklev. During the anti-Phanariot struggle the national and linguistic identity took on two forms: Unitarian and separatist. The Unitarians advocated a single Macedono-Bulgarian literary language which would be based on a mixture of Macedonian and Bulgarian dialects. The separatists, or Macedonists, felt that the Bulgarian literary language was too different from Macedonian to be used by them and they advocated a distinct Macedonian literary language.

After the Bulgarian Exarchate was established (1872), in 1890 most of the residents of Zelenic chose to join the Bulgarian Exarchist church. The Bulgarians promised the use of Old Church Slavonic (local dialect) in liturgical services and educational literature. As well, villagers did not have to pay for sending their children to school and church services were free and where there were fees, they stayed in the community to support the church and school. It is no wonder that villagers chose a combined Macedono-Bulgarian union that promised to preserve the Macedonian identity rather than remain under the corrupt and ultra-nationalistic Greek Patriarchate. But the Church of the Exarchate was really occupied in creating Bulgarians as even official church documents such as birth, marriage and death certificates, all bore Bulgarian subscriptions and seals.

Called Bulgarian but written in Macedonian

There is a plethora of Macedonian literature from the 19th century written in the native tongue which demonstrates beyond any doubt the existence of the Macedonian language and its rich dialects. The Macedonian name was not always employed, particularly during the earlier years of the national awakening, the local Macedonian vernacular most certainly was used. Hence, one only need read a song or poem recorded by the likes of the Miladinov Brothers from Macedonia to realize that despite the terminology used, what exists there is purely literature in the Macedonian language.

Church Slavonic (or, in the South, Macedonian) was still regarded as the language of the high style of writing from the time of St. Cyril and Methody who used the language of the people who inhabited the Thessaloniki, Florina, Kastoria, Bitola and Ohrid area. It is this language that missionaries were sent out from especially Ohrid to the rest of eastern Europe.

In 1840, Kiril Pejcinovik’s “Comfort to Sinners” a book of teachings and prayers, published in Salonika in 1840 was an important step for the history of the modern Macedonian standard language and for the documentation of the Macedonian national awareness.

1852-1853 – The printing of the Kokinovo Gospel in Thessaloniki by Pavel Bozigropski. Written in what is now Greek Macedonia during the first half of the 19th century. It contains a Greek Evaneliarium (Gospel lectionary for Sunday services) and its Macedonic translation, both written in Greek letters.. What makes the manuscript unique is its bilinguality, and the fact that both the Greek and the Macedonic text represents the vernacular, not church language. The Macedonic part is the oldest known text that directly reflects the living dialects of Southern Macedonia and is the oldest known Gospel translation in Modern Macedonian.

The Konikovo Gospel is thus an extremely rare and precious testimony both to Macedonian literary activity and at the same time a valuable resource for an inadequately attested but linguistically important Macedonian dialect.

Grigor Prlicev with his poem “The Serdar” (“O Armatolos”) won first place, the laurel wreath, a cash prize and he was named the second Homer (Athens 1860). Studying in Berlin or Oxford was part of the award, but that award could only be obtained if he renounced all Slavic (Macedonian) in it – and he declined it. In 1871 he published a translation of the Iliad but was heavily criticized and even ridiculed by Bulgarian critics for not using the Bulgarian literary language. From then until the end of his life Prlicev fought with the carriers of foreign influence in his homeland.

The very appearance of Macedonian textbooks at that time indicates the development of a Macedonian national consciousness. Sixteen textbooks published between 1857 and 1880 by Partenij, Makedonski, Sapkarev and Pulevski were indicative of the development of Macedonian national unity. In his 1875 ‘Dictionary of three languages,’ Gorgi Pulevski stated that the Macedonians constituted a separate nationality and advocated a Macedonian literary language and a free Macedonia.

H.G. Lunt (Harvard linquist) who wrote the first English grammar of the Macedonian language in 1950, stated, “this cannot possibly reflect a feeling of Bulgarian nationality.”

These textbooks were directly connected with Macedonian separatism by teaching children that they were not Bulgarian. They show that Macedonians did not all think of themselves as Bulgarians, and they demonstrate that the “Macedonian Question” was not only an issue at the Berlin Congress of 1878 but a problem which had developed at least twenty years before the Congress.

Even though in 1848 Russian Slavist Victor Grigorovich described Zeleniche as a Bulgarian village, the language (dialect) was Macedonic. The term Bulgarian has a long history of being used in-discriminately for the Macedonians living in the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) but, how can you call Macedonians Bulgarian when the Bulgarians had not yet developed their own literary language, in fact the Macedonians had started developing their own long before?

In “Ethnography vilayets Adrianople, Monastir and Salonika, ” published in Constantinople in 1878 which reflects the statistics of the male population by 1873, Zelenic is listed as a village with 450 households with 628 inhabitants (male) and 650 inhabitants Muslims. In 1889, Stefan Verkovich writes about Zeleniche as:

“The green village lying in a direction Neveska (Nymfaio) and placed on a level with 30 Muslim and 60 Macedonian houses. The tax is the first piastres 4100 and the second 9200 piastres. Its inhabitants are engaged in agriculture and others. Friday becomes market day”.

Becoming Greek rather than Being Greek!

From the time of the first inhabitants of the village of Zelenic around 1396, the people’s ethnos was Macedonian and the liturgical language in the three churches was “Old Church Slavonic” – Macedonic. The use of Greek was only forced upon the inhabitants (for the first time ever) in the twentieth century. The process of becoming Greek rather than being Greek defined the evolution of political and cultural agendas encompassing both the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. It was the beginning of the “Great Idea” of assimilating regions outside the confines of the state. The Greek state and the Eastern (Greek Patriarch) Orthodox Church in Istanbul perceived the Rum-millet as Greeks (either as carriers of the Romeic culture or as conscious co-inhabitants with the Greek national ideology).

Christians, regardless of ethnicity, were generally viewed as Greeks due to the sole jurisdiction enjoyed by the Constantinople Patriarchate in Macedonian from 1767-1870. Thus, from the mid-nineteenth century on wards the emphasis of Greek nationalism (Greekness) was given to religion. The integration of a Byzantine past and the definition of the Byzantine Empire was promoted as exclusively Greek. In reality, the Byzantine Empire was an empire of a federation of different ethnic Christian peoples of the Balkans. The inclusion of the Macedonians to the historical schema of the Greek nation was a process that by the 1870’s was already in the minds of those who wanted to expand their “Great Idea.”

The aim of the Greek narrative was to first distort, and change, then oppress, conquer, amalgamate and assimilate the peoples with the Greek language and Greek Eastern Orthodox identity. With the unity of the Greek faith (Patriarchy) and the unity of the Greek language, they supported their aims of expanding the boundaries of Greece.

1870

The next big blow came from Istanbul again. There, in 1870 the Turkish Sultan by a firman (imperial edict) announced the establishment of an independent Bulgarian Church.

The “final” step in the “Church Question”, the Schism, drew borders between the Orthodox believers who deferred to the Patriarchate of Constantinople, those who wanted to reinstate the Macedonian Orthodox Church in Ohrid and the schismatics the ones who chose to submit to the Bulgarian Exarchate.

The years 1870-1872 witnessed the end of the anti-phanariot struggle and the Bulgarian rejection of a Macedono-Bulgarian linguistic compromise. Macedonians had barely freed themselves from the Greek Patriarch, now they had to struggle from being assimilated by the Bulgarians. In 1871, the newly formed Bulgarian Exarchate excluded the Macedonian representatives from its first council. A year later in 1872, the Bulgarians publicly adopted the attitude that Macedonians should learn Bulgarian.

In 1871-1872, the Macedonians and Bulgarians were more or less united in the so-called “Crkvena Borba” (Ecclesiastical Struggle) against the Phanariot Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople. Thus, Greek and the Greek Patriarchate constituted the major threats to the Macedonian language and nationalism during the middle of the nineteenth century. According to some historians, the Macedonians escaped Hellenization by remaining illiterate during the long period under the Constantinople Patriarchate, thereby preserving their Macedonian dialects and customs, which provided them with the prerequisites for a national awakening in the nineteenth century.

This gave a new direction to the development of social, political and economic conditions in the Christian territories (especially Macedonia) of the Ottoman Empire. The Bulgars made the fullest use of their autonomous church. They saw themselves as the protector of the Bulgarian interests, just as the Greeks used the Patriarchate in Constantinople to promote their interests.

Funds were readily contributed for the improvement of Bulgarian education as schools were opened. The people wearied of their ill-treatment by the Greeks, rallied enthusiastically to the Exarchist church. At the outset of the Bulgarian Exarchate, the Bulgarians did not limit themselves to the Bulgarian counties, they began activities in Macedonia.

Throughout Macedonia from Thessalonica to Ohrid, and from the frontiers of Thessaly up to Skopje, since the dissolving of the Macedonian Archbishopric of Ohrid in 1776, divine service was celebrated in the Greek tongue in the major urban centres. The national customs, to which Macedonian people were deeply attached, were persecuted. The Greek priests strove to eradicate Macedonian customs and replace them with Greek customs.

This did not occur in Zelenic, even from the dissolving of the Macedonian Archbishopric of Ohrid in 1776, the village continued to use Macedonian not Bulgarian as the liturgical service in the three churches. The construction of the two churches in Zelenic are dated to 1867 (St. Dimitri) and 1868 (St. George), before 1870 and any Bulgarian activities in the area. From the beginning up to 1904, church service was conducted in Macedonian. Only the small chapel on the mountain side to the north, St. Petka (Agia Paraskevi today) was used by four families who were Patriarchist followers in the village.

This Greek-Bulgarian conduct frustrated the Macedonian population and upon the appearance of the Uniate Church, the Macedonians, too, began to be converted by it. The centre of this movement was in southern Macedonia, where the Uniates established a church in 1857. The Bulgarians were quick to turn this popular discontent towards the Greek Patriarchate and the spread of the Uniate faith in Macedonia to their own advantage. When the agitation against the Greeks Orthodox Church and conversions to the Uniate faith first began in Macedonia, it was only a question of emancipation from the Greek Patriarchate and the restoration of the national tongue in the Churches, nobody thought of the Bulgars.

Orthodox Russia also considered the presence of the Uniate communities in Macedonia as a danger to Slav Orthodoxy and so began to send her agents to dissuade the people from joining the Uniate faith and to promote the Exarchists. Under extreme pressure from Russia, Macedonians were left with one way of attaining emancipation from the Greeks, and that was to join the Bulgarian movement. It is important to note that this step did not imply Bulgarization, but only a joint struggle against the Greeks for the use of the Old Church Slavonic tongue in the Church. The struggle which the Macedonians had (against the Greeks) from the beginning, did not bear a Bulgarian character, nor prove that the Macedonians wished to become Bulgars.

The Macedonians (majority) listened to these counsels and helped to further the Bulgarian cause, upon the success of which their own cause was likewise to depend. The Uniate movement weakened and support for the Bulgarian movement increased. As such, Bulgarian agents found no difficulty in carrying on their propaganda.

- In place of the hated Greek Patriarchate they offered the people the protection of the Slav Bulgarian Exarchate.

- In place of the Greek language in the Church they offered them the Slav language.

- In place of the Greek schools, they gave them free schools in their own native tongue, where Greek school had an entrance fee and foreign language

Macedonians were confronted with a dilemma. The choice lay between four paths:

- Continue under the Greeks and the Partriarchate

- Abandon their faith and become Uniate

- Join the new Bulgarian Exarchate

- Fight for independence on their own

The decision was difficult as the nation (Macedonia) was by no means unanimous in its decision. A part remained with the Greeks, part clung to the Uniate faith, another went with the Exarchists. This became evident in Zelenic as the century came to a close, with priests, teachers and now paramilitary Serbia, Bulgarian and Greek groups competed against Macedonian freedom fighters for the hearts and minds of the people.

In last decades of the Ottoman rule, the conflicting interests of Greek and Bulgarian nationalisms (also to a lesser extent, Serbian), made Macedonia a battlefield of educational competition, religious propaganda, and at the turn of the century of guerrilla confrontations. In the period from 1870 until the end of the Balkan Wars, the local Macedonian population became the focus of the competing nationalist campaigns of Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece, each of which sent priests, teachers, and bands of guerrilla fighters to terrorize the local Macedonian population and force them to adopt a Serbian, Bulgarian or Greek nationality.

1878 San Stefano Treaty replaced by Treaty of Berlin

A number of key decisions were made at Berlin. First Serbia, Montenegro and Roumania all gained their independence from Turkey. Second, Austria-Hungary was allowed to occupy Bosnia-Herzegovina. And thirdly, Bulgaria was reduced in size; one part was Bulgaria, and another became a new state called Eastern Rumelia. Fourth, Macedonia was given back to Turkey.

After the 1878 Russo-Turkish war, the Russians signed a peace treaty with Turkey in March 1878 that allowed them to expand their area of influence in the Balkans. As soon as the success of the Russian war with Turkey (1878) was assured, the Greeks seized the opportunity and invaded Thessaly and organized insurrections in that province, in Epirus and in Crete. These movements were successfully opposed by Turkey, but at the conclusion of the incident Turkey was prevented from counter-attacking Greece by the Great Powers. But three months later, the Western powers rejected the Russian plan of San Stefano which created a large Bulgaria encompassing much of historical and geographical Macedonia.

Britain and Austria-Hungary could not sit back, and watch Russia become a major power and gain access to the Mediterranean; therefore, they openly threatened war with Russia. They demanded that the Congress of San Stefano be submitted to a congress to meet in Berlin. Fearing a war against the combined forces of Britain, Austria-Hungary and Turkey, the Russians agreed to the Congress.

This agreement became unpopular with Turkey. More territory was lost at the Congress of Berlin through negotiations, than she had lost through war against Russia. Turkey would have been better off if she hadn’t agreed to pressure Russia, especially since she had also given Cyprus to Britain as a base for use against Russia.

Macedonia was the only territory which Turkey regained but by giving her back to Turkey and not freeing her from oppression the Congress of Berlin left Macedonia up for sale to anyone other than the indigenous Macedonian population. As a result, the Congress became a failure in that the diplomats played the old game of trading off one thing for another, which only postpone the issue to be settled at a later date. By not establishing viable national Macedonian state, a peaceful solution to the Balkan problem was made impossible.

1881 Convention of Constantinople

This opened the door for Greece to move onto the scene. With the help of the Great Powers, Greece made claims for the extension of her boundaries. Article 24 of the Treaty of Berlin provided for the mediation of the Great Powers in case Turkey and Greece should not be able to come to terms with reference to the rectification of the frontier suggested at the Conference. After the tensions dragged on for several years, a solution to the question was finally resolved at the Convention of Constantinople on the 24th of May 1881. The new frontier began at the Gulf of Arta (Amvrakikos Gulf) and ascended the Arta (Arahthos River) to just east of Metzovo crossing the Pindus mountains to the Salambria (Pinion River) and east to the Gulf of Salonica. This boundary was to remain unchanged until the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913.

As one of the powers which had guaranteed the independence of the Greek Kingdom in 1828, Great Britain held the position that the Greek claims to the extension of their territories were greater (as of 1881) than the boundaries which the Greek City-States held in antiquity. This position was brought forward by Major J.C. Ardagh (later became Sir J.C. Ardagh, Major-General). He was part of the British delegation who was attached to the Special Embassy during the Congress at Berlin on June 3rd, 1878.

Majo J.C. Ardagh was appointed as Her Majesty’s Commissioner for the demarcation of the Greek Frontier (June 3rd, 1881). At the Conference of Constantinople, Major Ardagh communicated with the British Foreign Office on the issue of the new Greek frontier with his “Memorandum on the Ancient Boundaries of Greece,” which was received at the Foreign Office on February 24th, 1881. The information which Major Ardagh presented in his memorandum (quoting sources from antiquity) is listed below:

Memorandum on the Ancient Boundaries of Greece by Major J.C. Ardagh

“As the claims of the Greeks to an extension of territory are in some degree based upon the limits of Ancient Greece, I conceived that an examination of the early Greek geographers would throw some light upon them, and I have therefore looked over all the authorities which I have been able to procure, and annex extracts from them in Greek, with translations.”

” Strabo, Scylax, Dicaearchus, Scymnus, and Dionysius all concur in making Greece commence at the Ambracian Gulf, and terminate at the River Peneus. The catalogue of the ships in the Iliad, the various lists of the Amphictyonic tribes, the States engaged in the Peloponnesian war, the travels of Anacharsis, the description of Greece by Pausanias, and the natural history of Pliny – all give proof of the same fact, by positive or negative evidence; nor have I found anywhere a suggestion that Epirus was Greek, except that Dodona, the great oracle, though situated amid barbarians, was a Greek institution, and the legend that the Molossian Kings were of the house of the AEacide. When Epirus first became powerful, 280 B.C., Greece had long been under the complete ascendancy of the Macedonians, and after the fall of that Empire at the battle of Pydna, 168 B.C., it became a Roman province in 148 B.C.. The re-establishment of Greek independence in 1832 was exactly 2,000 years after the battle of Pydna.“

Document 41 of the Memorandum then continues with the “Notes from Authorities upon the Ancient Frontier of Greece. These notes are in the Ancient Greek language with English translations.

The San Stephano Treaty (1878) had freed Macedonia from Ottoman oppression but, the Congress of Berlin and Convention of Constantinople (1881) enslaved her once again by giving her back to the Turks. However, the Greeks obtained Thessaly, which led them to the gates of Macedonia, and from that moment they began diplomatic maneuvers towards the European powers, collaborated with the Turks, and at the same time, organized clandestine operations by sending agents into Ottoman territories to secure possession of Macedonia.

1891 Macedonian Uniate Orthodox Churches

Oral History states that in the village of Zelenic, there existed a group of people who wanted to preserve their identity through their language of “Old Chuch Slavonic” but realized that they could not do this by remaining under the Patriarchist or the Exarchist. Some chose to support the concept of a Uniate Church. This was short lived as in 1892, most of the village chose the Exarchist side. A year before this, the Macedonian archimandrite Teodosiy Gologanov, in a letter dated 21 June 1891 writes:

“We Macedonians have no such trouble from the Turks, long live the sultan, as from the Greeks, Bulgars and Serbs, who like vultures on the carcass attack this our suffered country and want to split it up.”

Given the close connection between the Orthodox churches with new local nationalism’s (Bulgar, Serb and Greek in this case) Metropolitan Teodosiy knew that no Patriarchate nor Exarchate would agree to restore the apostolic inherencies of the Ohrid Archiepiscopacy as a centre of the original Macedonian Apostolic Church. On 4 December 1891 Theodosiy wrote to Pope Leo XIII, in which he asks the catholic holy father on behalf of all Orthodox congregations in Macedonia “to receive us under his wing of the Roman Catholic Church after renewal of the ancient Ohrid Archbishopric, illegally abolished by Sultan Mustafa III in 1767.” As a result, the Ecumenical Patriarchate entered in “negotiations” with the Macedonian Metropolitan Theodosiy in order to somehow recover the eparchies in Macedonia lost with the non-canonical creation of the Bulgar Exarchate in Istanbul. Add to this, Russian diplomatic pressure exerted through the Exarchist church, Bulgarian paramilitary bands and Russian diplomatic attachés, claiming that the inhabitants of Macedonian villages were Bulgarian, the Uniate movement was defeated before it even started.

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Committee (IMRO)

By the 1890s the neighbouring states of Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria continued to intensify the political struggle for Macedonia. A church-sponsored drive for the spiritual and cultural life via propaganda, threats and the funding of state-sponsored campaigns of increasing violence with armed bands terrorized Macedonians.

When Bulgaria gained its independence in 1878, after the Russo-Turkish War, a large number of Macedonians emigrated there from the Ottoman Empire, where they attempted to found literary societies. The year 1893 saw the founding of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (Vnatresna Makedonska Revolucionerna Organizacija, or VMRO – in English -IMRO) in Salonika.

Bulgaria on the other hand, had the advantage of similarities in culture and language and were able to take advantage of indoctrinating the young minds of Macedonians who were sent to be educated in Bulgaria. The “National Macedonian Awakening“ was hijacked by Bulgaria into becoming a “Pan-Slavic” movement in liberating Macedonia from the Turks and Greek Patriarchate. The Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO – 1893) who’s main goal was to win autonomy for Macedonia from its Ottoman Turkish rulers was weakened by Bulgarian influence when they formed their own Macedonian organization the “Supreme Committee” in 1895. Thus creating two wings of IMRO, the Central Committee with aspirations of autonomy and the Supreme Committee with dreams of joining a “Greater Bulgaria.”

A secret organization named the National Society (Ethniki Hetairia) started in Athens in 1894 and had support from the Greek government, army officers and wealthy and influential citizens. In Belgrade, the Political Education Department (Politicko prosvetno odelenie) to direct Serbia’s efforts in Macedonia. In 1895, Macedonian refugees in Sofia founded a ‘Supreme Committee’ (Makedonski vurkhoven komitet) to organize the struggle for the ‘liberation’ of Macedonia, which, to the Committee, meant its annexation to Bulgaria. This Committee soon became closely linked with the Bulgarian Government and Crown.

From the early days there were always two Macedonian trends or movements. The Supreme Committee tended towards closest collaboration with the Bulgarian War Office and the Bulgarian Tsar. This wing only used talk of Macedonian autonomy or independence as a cloak for its real aim of Bulgarian annexation of Macedonia.

The other IMRO (Central Committee), was towards genuine autonomy or independence for Macedonia. In the early days of the movement, this wing preached brotherhood of all the peoples of Macedonia, not only Macedonians but also Turks, Albanians, Vlachs and Greeks, and it tried to preserve a certain independence from the Supreme Committee and the Bulgarian War Office.

At first, both organizations advocated autonomy for the province as a means of realizing reform while resisting partition among the neighbouring Balkan states. Though their solutions to the Macedonian problem may have appeared similar, the two organizations were very different in character, as were the routes they mapped out to reach autonomy, and the purposes of that autonomy.

IMRO was founded and led by young intellectuals, often teachers, who planned to achieve autonomy through a general uprising of all the peoples of Macedonia, attracting the aid of the Great Powers. IMRO’s immediate aim, however, was to prepare for revolt in secrecy, by both educating and arming the peasants of Macedonia for armed struggle. Even though they served the Exarchist school organization, they were entirely hostile to its aims and merely used it as a means of earning a living and especially of coming into contact with the Macedonian youth to promote Macedonian interests.

The Supremists, on the other hand, were based in Bulgaria, and led by Macedonian emigres and native Bulgarians, often army officers, with a poor opinion of the revolutionary potential of the peasantry. Their main goal was to annex Macedonia byt making it part of a greater Bulgaria in a “Panslavic” movement supported by Russian interests.

While IMRO insisted on Macedonia’s need to liberate itself, the Supremists planned to import revolution from Bulgaria. In the event, Supremist incursions helped precipitate the ill-fated uprisings of I903, in spite of IMRO doubts over the timing of the revolt. Nevertheless, Bulgaria was its main source or channel for arms and money so, this independence was limited.

One of the first items to be implemented by IMRO was to adopt the Bitola (Monastir) dialect as the basis of the literary language, since it was distant from Serbian and Bulgarian and central in Macedonia. The members of IMRO not only wanted political freedom but also, cultural and linguistic freedom from Turkey and the Exarchate. The first article of its rules and regulations was:

“Everyone who lives in European Turkey, regardless of sex, nationality, or personal beliefs, may become a member of IMRO” (Barker, 1980)

One of the first actions of the Supreme Committee was to organize a large-scale military incursion into Macedonia in the summer of 1895. A number of detachments commanded by reserve officers and volunteers from the Bulgarian army entered Macedonia to ignite revolution, but they suffered heavy casualties in skirmishes with Turkish troops and retreated back to Bulgaria.

IMRO remained on the sidelines during this incursion as their members did not trust the Supreme Committee and that this insurrection would have disrupted their plans. IMRO sought material and financial support from the Supreme Committee and when that failed, they approached the Bulgarian government, but they too did not trust the autonomous sentiments of IMRO acting in a manner harmful to the Bulgarian foreign policy on Macedonia.

In 1896, as a gesture of goodwill (fearing a split with IMRO), the Bulgarian government offered cash and weapons and IMRO willingly accepted the gifts but refused to agree to the conditions. In turn, the government decided not to hand over the promised cash or to supply ammunition with the rifles, telling IMRO they would have to pay for the ammunition although the Bulgarian government knew IMRO had no funds. The incident convinced IMRO that the Bulgarian government was more interested in controlling IMRO than in aiding it, and they refused to have any further dealings with the Bulgarian government. From the outset the Supremists competed with IMRO, sought to take it over, and when it failed, became a determined opponent.

The Macedonian peasantry thought about liberation but knew they would have to pay a cost by siding with the Bulgarians. Villages needed material proof of IMRO’s organizational strength and of the effectiveness of its means and their applicability in the case of an armed struggle. Thus, IMRO came more and more to depend on “forced contributions” and “get-rich-quick” schemes to supplement the treasury.

Robberies, extortions, and kidnappings were all considered as possible expedients. The use of illegal means to obtain money in order to purchase weapons to free Macedonia from the Ottoman yolk was a required sacrifice. In the words of IMRO’s leader Goce Delcev, “There can be no boundaries to such sacrifices even though they might destroy your name and honour.”

There were many schemes that were proposed, none wilder than that suggested to the American consul in St. Petersburg (Russia) that a detachment of Macedonian volunteers be sent to help the Americans in the Spanish-American War in exchange for American financial support of the Macedonian struggle. Thus, IMRO began to organize bands to achieve the collection of money, and the shipment of weapons through robbery or punishment. From the end of the century, to the start of the next, IMRO competed for their rightful place among the Macedonian people by also having to battle their own people who had been bribed, threatened or assimilated into accepting the national narratives of the newly established states of the Balkans.

In this context of over-bidding nationalist propaganda by their neighbours, the Macedonians created the Macedonian Internal Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in Salonika in 1893. In line with the Macedonian Kresna uprising of 1878, IMRO’s initial objective was autonomy with implementation of the reforms provided for by Article 23 of the Berlin Treaty. Seeing that Bulgaria had forcibly annexed the autonomous Eastern Rumilia, the Macedonians refused to associate with the Bulgarians in order not to experience the same fate. The Bulgarian response to this act of Macedonian independence was the creation in Sofia in 1895 of a committee called “Macedonian” under the control of the Bulgarian government. At the IMRO Congress of 1896 in Salonika, the Macedonian revolutionaries decided that independence should be achieved by a revolution.

Victor Bérard, a French diplomat, politician and Hellenist

In 1896, Victor Bérard, a French diplomat, politician and Hellenist visited Macedonia and noticed the deterioration of the living conditions of the population in Macedonia. He explained at the time that it was exploited by the Turks and the Greek clergy, writing: “Together also interested in keeping this Macedonia, the Sultan and the Patriarch were working and were able to easily keep it in the dark.” At the same time, this population was subject to Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian propaganda.

The arguments of the different parties by Victor Bérard

“The Greeks proclaim themselves in Macedonia the only legitimate heirs. If the coast is Hellenized, the whole interior is Slavic.”

“Bulgarians present themselves to the Slavs of Macedonia as liberators and educators, they bring from the outside progress and light, but also impose their language, their literature, their way of being and thinking; they want to annex Macedonia, conquer it on behalf of Sofia.”

As for The Serbs, they “present themselves more as elder brothers who give advice not orders and examples rather than a ruler. They proclaim the Macedonians patriots, they collect Macedonian songs and, under the label of Serbian songs, make them learn in their schools. In short, they pose as representatives and not as conquerors of Macedonia.

Serbs and Bulgarians argue that the language of the Slavophone Macedonians would be for the former, Serbian, and Bulgarian, for the latter. In reality, the creation of Slavic writing began with the Christianization of the Macedonians in their language from the 7th century onset. Adaptations of the Greek alphabet to the sounds of the Slavic language led to the creation of the Glagolitic alphabet by Cyril and Methodius and their translation of the Church books from Greek into the language of the Slavs installed around Salonika. The fact is that the Bulgarian and Serbian states occupied Macedonia for some time in the Middle Ages and they derive historical rights from it. But their arguments are almost identical, their demands cancel each other out.

As far as the Greeks’ claims were concerned, they never, as a state, occupied Macedonia before 1912, since it was only in 1830 that they had their first state. Their argument was linguistic and based on antiquity: the chancellery of the Kingdom of Macedonia used Attic Greek and the Macedonian aristocracy was bilingual, but the people were “barbaric” because they did not speak Greek. However, in 1913, it was precisely on the basis of this fallacious argument that the powers attributed half of ancient Macedonia to the modern Greeks.

Analysis of the Macedonian Question 1890s

Victor Bérard, a Hellenist and Homer’s specialist, devoted himself to the study of the ethnic and political situation in Ottoman Macedonia from 1890. He did archaeological excavations in Greece and, visiting Macedonia in 1890, he betook his inner problems and the living conditions of the population. In the chaos of Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian nationalist propaganda and even Romanian. His first findings on the state of Macedonia and its future are equivocal.

In his first book entitled “Macedonia” he describes the advantages of the geographical location of the region on the Morava-Vardar axis that connects Central Europe to the Aegean Sea and its territory, largely unchanged since Philip II, king of the Macedonians from 359 to 336 BC.

When he returned in 1896, he found that since his first visit, because of Turkish oppression, Albanian raids, the interference of the powers and the propaganda of the new Southern Balkan states, the situation of the population had become unbearable.

At the time, the ethnicity of the population was defined by the propaganda of the pretenders to possess Macedonia. The term “race” was used without definition criteria. This is why Victor Bérard, at the beginning of his investigations, distinguished “races” of Greeks, Bulgarians, Serbs, Valaques (or Romanians), while admitting that there were also Macedonians.

Subsequently, the more the investigation progressed on the ground, the less he made these distinctions, and for in his second book (Pro Macedonia) he claims that Macedonia is inhabited by Macedonians and this despite the indoctrination of populations by foreign propaganda.

Indeed, the year Victor Bérard published in Paris the results of his surveys in Macedonia, William Gladstone (1809-1898), former British Prime Minister, wrote: “Why should Macedonia not be for Macedonians like Bulgaria to Bulgarians and Serbia to the Serbs? Victor Bérard said the same thing when, at the end of his investigations, he wrote that “Macedonia should be left to the Macedonians.” The Macedonian revolutionaries told him that they would organize their future state into a federation or confederation.

This idea of federalism and respect for the rights of all peoples, regardless of ethnicity, language or religion, was the foundation of the socialist ideology of the late 19th century to which Victor Bérard adhered. It was also the basis of the project of the Macedonian revolutionaries he knew.

The federalist project for Macedonia was published in France in the Socialist Review in 1895 and 1896 in the journal “Social Question” by Panayotis Argyriades (a French Lawyer born in Kastoria 1849-1901) who made a clear distinction between Greeks and Macedonians and promoted the ideology of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization created in 1893 in Salonika. He went on to say,

“The small Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian states are vying for possession of Macedonia, availing themselves of all kinds of chauvinistic and historical reasons, invented in support of their interests, not realizing that if it were necessary to rely on historical reasons, rather, it is Macedonia which would be entitled to possess all the lands that want its absorption, for it is only it that has once conquered and possessed them.”

On his first visit to Skopje in 1890 and from what he had seen, he had concluded that the Macedonians, subject to Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian propaganda, preferred Turkish serfdom to the powers of the newly created southern Balkan states Powers. But in 1896 he found that there had been a great change, that the conditions had worsened and that the three suitors for possession of Macedonia were much more virulent. With their churches and schools, they were conditioning the Macedonians and turning them into Greeks, Bulgarians or Serbs, while those pulling the strings were in Vienna, St. Petersburg, London, Paris and Istanbul.

The nineteenth century was the period of the Macedonian Revival. People all over Macedoia began to resist the policy of Hellenization imposed on them by the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinopole. “Zelnicheny” were no exception.

Zelenic from the 1840s and on…

One could meet merchants, artisans, blacksmiths, carpenters, weavers, butchers, stay at inns and shop at the popular market every Friday and later even every Wednesday too. By the mid nineteenth century, the land was not enough to support the village’s population and this led many villagers to leave on mass to find their fortunes abroad. Some left for Istanbul, Romania, Egypt, Varna, Bulgaria, while others left for Argentina and the United States. They became “Pechalbari” migrant workers and many returned to the village and made various investments with the money they had earned, bying fields, plots of land and building beautiful neoclassical houses.

Starting in the 1840s, the village began prospering with increased trade in the region and an inflow of money being sent back by its migrant workers. With this wealth, Villagers were able to build 3 churches and open its people to a brand-new world. First to be noticed was the clothing styles changed from the traditional Macedonian garments to new fashions from the modern urban centres. Stories of men being made fun of because they wore suits were the talk of the village. Agricultural products were being sold at the local farmers market every Friday and by the end of the century two markets, the other every Wednesday. The location of the market was in the Muslim neighbourhood (mahala) south of the “Stara Reka” (Old River).

The village had a perennial source of water from three rivers and the mills were located near these sources of water. The diagram below depicts a typical horizonatal water mill with the flow of water from a higher elevation spinning the turbine (originally made of wood and later of iron) which then made the top circular stone to spin and grind grain that was poured in the middle whole of the top stone.

Click on the following links to view a manual millstone and a water mill in action. The 23 mills in the village are an indication of those families, and the village were able to grind their own grain and even rent the service of their facility.

The economic prosperity resulted in gaining the support of the Muslim villagers who also prospered from the trade of goods and services. The abundance of water with three sources (Stara Reka; Strebano Reka; and Isvoro mountain spring) produced 23 water mills, with most on the slopes of the northern mountain powered by the “Izvoro” spring. This is not only an indication of the various grains produced in the fertile valley, but also, it would attract people from other villages bringing their grain for milling. The free trade and exchange of grain was permitted only within the administrative district (Kaza).

Bread was deemed as “sacred” in the Ottoman Empire and there were regulations on flour and bread. There were bread supervisions and punishment due to infractions that even resulted in death sentences if millers/bakers did not follow established rules. The number of “Asiyabs” (water mills) were registered to the Cadastral Record Books of the state. Each millstone generally consisted of a couple of hard basalt stones of 120 cm diameter, 25cm thickness with a 15cm hole in the centre. The stone in the bottom was fixed, and the upper stone would rotate to mill the grain poured in the centre hole.

Mulberries were also being produced and traded in the market. This supports the view that there may have existed silk production in the village or at least the trade in the raw materials needed to produce the fabric. This was evident as from the first Tefter (census) in 1481, mulberries (Tsarnitsi) were being taxed. The leaves of mulberries (genus Morus) are fed to the silkworms to produce silk. The right to buy coccons and silk production constituted a mukataa (tax farming unit) and many local Agas (local lord) owned that monopolistic right. So, Zelenic may have been part of an incorporated web of towns and villages in the region used to produce raw silk. The process of silk production is known as sericulture. … Extracting raw silk starts by cultivating the silkworms on mulberry leaves. Once the worms start pupating in their cocoons, these are dissolved in boiling water in order for individual long fibres to be extracted and fed into the spinning reel. Raw silk is then produced and sold to intermediaries. Since the village had an abundance of water, mulberry bushes different from the tree, were harvested. Most of the “Yame” the convergence of all three water sources into one, at the eastern part of the village below the present-day soccer field was used for mulberry production. We do not know if the original Christian inhabitants produced silk, but we can make a connection to the Yoruk Muslim colonists who most likely brought the knowledge of silk production to the village. As of the first census in 1481, it also names some Muslim families on the register.

The city of Bursa was the first capital of the Ottoman Empire and conquered from the Eastern Roman Empire (known academically as the Byzantine Empire) in 1326. Before the conquest of Constantinople (present day Istanbul) with the continuous expansion of the Ottomans there was a shifting of the centre of East-West trade to Bursa. In a parallel development, the ancient silk road passing through Anatolia gained importance. Ottomans gained control of this route after the conquest of the Karaman territories and especially Konya in 1468. According to oral history from the ancestors of those Muslims settled in Zelenic, the Yoruk were resettled by the Ottoman from their home region of Konya. It is these nomadic Yoruk people who must have brought the art of silk production to Zelenic. Ironically, after the 1922 Greco-Turkish war, in the exchange of refugees, the former Yoruk were resettled back in Turkey and Christians from Asia Minor and some from Bursa were resettled in Zelenic. One of these families in particular, my great grandfather brought with them the art of silk making and continued to produce silk up until the end of the Greek Civil War in 1949.

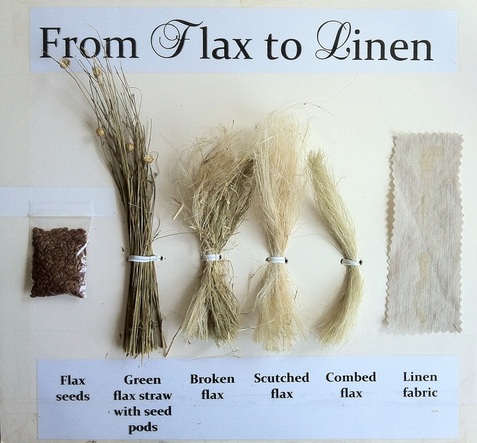

Another commodity produced was flax (Linum usitatissimum) and the long fibres from the bark of the flax plant is spun to make Linen yarn. In order to retrieve the fibres from the plant, the woody stem and the inner pith (called pectin), which holds the fibres together in a clump, must be rotted away. The cellulose fibre from the stem is spinnable and is used in the production of linen thread, cordage, and twine. The village most likely produced the raw material and the finished product, linen. Flax is also on the Ottoman census (Defter) from 1481.There is no mention of the sale of flax seeds for milling or oil production, even though flax oil was produced in Anatolia.

The other agricultural staples of the village included, vegetables (tomatoes, cucumbers, peppers, leeks, onions, garlic, Jerusalem artichoke, potatoes, beets, various beans and legumes), fruit trees (apples, pears, apricots, peaches, cherries, quince) and nuts (walnut, chestnut, hazelnut). Not to mention dairy products from water buffalo, sheep, goats, and poultry. Fabrics made from wool, silk and linen as already mentioned were also produced and sold.

Trades and guild also began, but to a lesser extent due to the small population threshold of the village. Most of those who entered the guilds were those who had moved to the urban centres where they entered and learned new skills so, they remained there as their businesses were much more profitable. Trades such as, shoemakers, watchmakers, tinners and platers, tanners (leather), tailors, etc..

By the mid nineteenth century, many hard-working emigrants from the village had become quite wealthy and Zelenich was one of the more prosperous villages in the Lerin region. The mid-nineteenth century was the period of the Macedonian Revival. People all over Macedonia began to resist the policy of Hellenization imposed on them by the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinople. “Zelenicheny” were no exception.

According to the old residents of the village, the first Macedono-Bulgarian school in Zelenich was opened by Dinkata in 1870, in the home of Georgi Jouklev. After the Bulgarian Exarchate was established, by 1890 most of the residents of Zelenich chose to join the Exarchist church rather than remain under the corrupt and ultra-nationalistic Greek Patriarchate.

The Macedonians held the church of St. George while a small minority of Patriarchists were given the church of St. Demetrius. But the fanatical Greek bishop of Kostur (Kastoria) would not leave the residents of Zelenich in peace. During the Risso-Turkish war, the Greek bishop succeeded in closing the Macedono-Bulgarian school down (1877-78). However, it re-opened soon after the war ended. By 1883, the Macedono-Bulgarian school had 120 pupils, and night courses were organized for older students.

Disturbed by the school’s progress, the Greek Bishop again tried to have the school closed. Luckily, he did not success. However, the Greek bishop did succeed in murdering Father Vasil, who had recognized the Bulgarian Exarchate. In 1890, the Greek bishop attempted to seize the church of St. George. Stefo Gotev lost his life because he led the opposition to the Greek bishop.

Still the Greek bishop did not learn his lesson. Another attempt to take over St. George’s was made this time by the depraved fanatic, “Bishop” Karavangelis, in 1898. Again, the attempt was a failure. The woman in Zelenich organized an effective protest demonstration and stated that under no condition would they let the church be taken over. Karavangelis soon saw that these women meant business and left the village.

Fires in the Mountains

With all this prosperity from the Macedonian migrant workers and entrepreneurs in the urban centres, the rural regions in the mountains of Macedonia were on fire. They were on fire with Bulgarian, Serbian and Greek organized militias, Ottoman soldiers, Albanian bandits, and Macedonian freedom fighters, a “powder keg” ready to explode. The competition for Macedonia would soon reach yet another level of aggression, that being foreign national armies vying to expand their boundaries at the expense of a rightful and legitimate movement and cause.

The nineteenth century was a period of the Macedonian Revival. People all over Macedonia began to resist the policy of Hellenization imposed on them by the Greek Patriarchate of Constantinopole. “Zelenicheny” were no exception. By 1890, most of the residents of Zelenic chose to join the Bulgarian Exarchate rather than remain under the corrupt and ultra-nationalistic Greek Patriarchate. The majority Exarchists of the village held the church of St. George, while a small minority of Patriarchist were given the church of St. Demetrius. But the fanatical Patriarchist Bishop of Kostur (Kastoria) were not to leave the residents in peace.

During the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78, the Greek Patriarchist Bishop succeeded in closing the Macedono-Bulgarian school down. However, it re-opened soon after the war ended. By 1883, the school had 120 pupils and night courses were organized for older students. Disturbed by the school’s progress, the Greek Bishop again tried to have the school closed. Luckily, he did not succeed. However, the Bishop did succeed in murdering Fahter Vasil, who had recognized the Bulgarian Exarchate. In 1890, the Greek Bishop attempted to seize the church of St. George but, Stefo Gotev led the opposition to the Greek Bishop in defending the choice of the village in front of the Turkish court in Bitola. In doing so, Stefo Gotev was murdered.

In 1898, the Greek Bishop of Kostur attempted to take over the church once again but, this time the women of Zelenic organized an effective protest demonstration and stated that under no condition would they let the church be taken over. Throughout the history of both churches in Zelenic, the language used for services was in the local “Old Church Slovanic” – Macedonian. This was the case in most villages of the region, as the locals defended their Macedonian churches. The lable of “Patriarchist” or “Exarchist” did not signify nationality or ethnicity, it affiliated people with the sect of Christianity that they were to pay their taxes too and the language they were forced to use for church services. A process of indocternation and assimilation. This was challenged with a genuine local Macedonian movement.