Unrest in Macedonia

From the beginning of the 18th century, we have more reliable information about Macedonia. Reports from the European consuls in Thessalonika (Solun) were more extensive in regards to questions of economic matters. The first decade of the 18th century was a period of peaceful relations between Turkey and the Central European powers.

However, unrest among Christians was being created by the excesses of the administrators and the severity of the tax-collectors. This inflamed situation gave rise to periodic outbreaks of desperate retaliation. An increase in the number of rayas (Christian farmers) fled to the mountains and embarked upon a career of robbers and criminals. The state of lawlessness most likely came about with the help of the existing military auxiliaries or guards (voynuks, martolosi, derbentgi, zampites, armatoloi, etc.).

Voynuks – were members of the privileged Ottoman military social class established in the 1370s or the 1380s. Voynuks were tax-exempt non-Muslim, usually Slavic, and Ottoman subjects from the Balkans, particularly from the regions of Macedonia. The term ‘voynuk’ is derived from ‘voynik’ which in Macedonian means “soldier.” This category of citizens existed in medieval Macedonia. They were originally members of the existing Balkan nobility who joined the Ottomans in the 14th century and were allowed to retain their estates because the Ottomans regularly incorporated pre-Ottoman military groups, including voynuks, in their own system in the early period of the Ottoman expansion in order to accomplish their new conquests more easily. The social class of voynuks was established in the 1370s or 1380s.

A Sultan’s firman of 1704 reports of “robbers and criminals” active in Macedonia. In April 1705 brigands revolted in the Kaza of Veroia plundering and killing the Muslims of the countryside. The revolt was eventually quashed and the brigands were caught and hanged. At the same time, anarchy continued to reign throughout the rural districts, particularly in Western Macedonia from the kazas of Anaselítsa (east of Siatista and Kozani) as far as Monastir and Prilep, where Moslem ‘martolosi’ and bandits preyed on the inhabitants, without distinction as to whether they were Christian or Muslim.

The Orthodox peasants’ worsening economic situation and their harsher treatment by corrupt administrators and fief holders had political repercussions. Some peasants ran away and joined the growing number of bands of outlaws (klephts in Greek, khaiduts in Bulgarian, haiduks in Serbian, and ajduts in Macedonian). This movement, which became a feature of the declining empire, increased instability and insecurity throughout the Balkans, especially along major trade routes and around commercial and administrative cities.

Throughout this time period, the Ecumenical Patriarch in Istanbul (Constantinople) was eager to restore its authority over the Macedonian Peninsula and to diminish the power of the Macedonian Apostolic Church. This was done by illegally giving the ecclesiastic jurisdiction over different eparchies in the hands of the newly non-canonically created national-political churches.

This is no different then what the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Bartholomew I on January 5th, 2019, officially recognized and established the Orthodox Church of Ukraine and granted it autocephaly (self-governorship), making it independent from the Russian Orthodox Church. In 1708 the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople (Istanbul) granted autonomy to the Serbian Orthodox church Sremski Karlovci by granting it jurisdiction over numerous Macedonian eparchies. At the same time, the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople continued its interference in the rest of the Macedonian eparchies in Macedonia.

The outbreak of the Venetian-Turkish war in 1715 brought a serious decline in safety upon the roads in Macedonia, and other parts of the Balkans, for the robbers saw in the hostilities an opportunity for extending their theatre of operations. With Austria’s involvement in the conflict and the spread of hostilities to the northern frontiers of Turkey’s Balkan possessions, the situation deteriorated still further.

Throughout the duration of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian wars against the Ottoman Empire, and even after the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718), a large number of Ottoman deserters took to robbing and killing, thus adding to the chaos. Also, many Albanian “martolosi” in the Monastir and Florina areas, embarked upon paths of crime and extortion at the expense of travellers passing through the narrow mountain passes of the region.

The treaty of Passarowitz (21 July 1718), which was a victory for Austrian diplomacy, marks a stage of considerable significance in the history of the Balkan peninsula, and not least of Macedonia. Having incorporated into her territory Belgrade, the greater part of Serbia, lesser Wallachia, and the Banat of Temesvar, the Austro-Hungarian empire had begun its transformation into the mighty state which the world new from the 19th century until the end of the First World War (1914-1918). She was now, in 1718, not so far away from Macedonia and her great commercial port, Thessalonica, through which the merchandise of Central Europe might be exported and the produce of the Levant correspondingly imported.

Trade

For the first time, the Balkan peoples were given an opportunity to enjoy the fruits of this new commercial activity, and through their participation to acquire both wealth and social power. It was Macedonia which was to derive the greatest benefit from these developments, particularly in its western and central provinces, with Thessalonica as the principal trading centre. In the 1700’s, France dominated trade with the Austrians second greatest in volume of trade, thanks to the long border they shared with the Turks. German merchants bought large amounts of cotton both raw and processed, the latter being dyed red in the workshops of Veroia (Ber), and in the villages and townships of Thessaly. Soon, German, French, English, Dutch and Venetian merchants were competing for Macedonian products. They all set up consulates in Thessalonica.

The peasants in these regions of Macedonia, on the other hand, whether small proprietors or working as cultivators on the extensive properties (chiftliks) belonging to Turkish ağas (master), were forbidden to export their produce directly. They were obliged to sell their produce to the Turkish ağas, who exploited them in every way, buying their product at lowest prices and re-selling it at far higher rates.

During the 18th century, the towns and cities throughout Western Macedonia were enjoying a period of rapid economic expansion, and a number of them developed into centres of considerable importance, i.e. Moschopolis, Korytsa, Siatista, Kozani, Kastoria, Ohrid, etc. The last named city had, in particular, a flourishing industry of furs and hat-manufacture; and such was her prosperity that even the finances of the archbishopric improved. Trade fairs sprung up in many major towns and cities as trade was conducted through “trade fairs.”

Zelenic had two such trade fairs or “pazars” – local markets a week. A testament not only to the produce of the area but also the importance of the village/town.

Around the middle of the 18th century we find the following goods being imported into Thessalonica from abroad: from France, woollen textiles of various qualities, paper, white soap and sulphur; from America, sugar, indigo, coffee; textiles from Britain and Holland, silks from Venice and Messina, linen from Rome, paper from Genoa; and from other sources came tin-plate, wrought-bronze, china, nutmegs, cloves, cinnamon, pepper, ginger, medicaments, wire, Brazil-wood, tin, lead, lead-shot, etc. Caravans of 100-120 pack-animals left every week from Thessalonica for Sofia, Skopje, Monastir and Stip.

Even though there was considerable expansion of trade and industry throughout Macedonia, crime remained high. Such vigorous commercial activity is quite remarkable considering that it took place amid conditions which were far from favourable. Southern Macedonia (present day Greek-Macedonia) continued to be a hot-bed of rebels (ajduks) and bandits. In such regions where the Macedonian population was dominant, it was the bandits and ajduk (freedom fighters) that were chiefly responsible for the wide spread disorder.

In 1759 the Porte (Ottoman central government) began to take action against the most troublesome of them all, the Albanian mercenaries. Villages would unite to word off the common danger.

The system’s degeneration and corruption also hurt the patriarchate of Constantinople and the Orthodox church as bribery permeated the millet’s (court of law) operations. The Phanariotes – ‘‘Greeks who entered the Ottoman service and gained great power and wealth as administrators, tax farmers, merchants and contractors’’ – controlled the patriarchate and through it the millet. The Greek ethnic element, gradually assumed complete control; Greek displaced Church Slavonic and became the church’s exclusive language in the empire. This development slowed the spread even of limited education and culture to the vast non-Greek majority of Macedonians, Romanians, and Albanians under the patriarch’s jurisdiction.

Due to numerous uprisings against the Turkish occupying forces in Macedonia, in which the church had a leading role, and under cunning accusations from the Ecumenical Partriarch in Constantinople/Istanbul, in 1767 they abolished the autocephalous Macedonian Apostolic Church. The overall church jurisdiction of the Macedonia Peninsula passed then under the apostate and treacherous Ecumenical Patriach of Constantinople/Istanbul.

1767 – Abolishing the Autocephalous Macedonian Apostolic Church

1767 – “Required to use Greek as the Liturgical Language in all Orthodox Churches

It is from this point on – 1767, the Ottoman, with the assistance of the Greek Ecumenical Patriarch of Istanbul (Constantinople), devised a plan to combat national movements in the Balkans. All Orthodox eparchies in Macedonia, Serbia, Bulgaria and Rumania were now required to use Greek as the Liturgical language in all Orthodox Churches. By instating Greek as the liturgical language of all Orthodox churches in the empire, the demographic narrative of the Balkans begins to change.

As a result, Ottoman defter’s (was a type of tax register and land cadastre in the Ottoman Empire) recorded the population as either being Muslim or Greek. The “GREEK” registration referred to the individuals religion and not their ethnicity. The category “Greek” is tricky because in censuses this included all Orthodox Christians until the creation of the Bulgarian Exarchate. The patriarchate attempted to Hellenize as much of the non-Greek population as possible in pursuit of the “Megali Idea – Μεγάλη Ιδέα.” “Great Idea” was an irridentist concept that expressed the goal of reviving the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire by establishing a Greek state over all of the Ottoman Empire. In fact, this was achieved in 1767 as the Greek language became the sanctioned language that ruled over all Christians in the empire.

So, all Romanian’s, Bulgarian’s, Serbian’s and Macedonian’s were now categorized as being Greek. This system of registration was then used by Greek nationalists of the 19th and 20th centuries to usurp the true identity of the Macedonian people and land and promote the manufactured Greek irredentist ideals and views.

The sanctioning of the Greek Ecumenical Patriarchate as the sole ruler of all Christians in the Balkans led to animosity between the Orthodox eparchies. The situation enabled the Porte to play churches against each other, to exact heavy payments from Patriarchs and other religious dignitaries, and to banish, dismiss, and even execute the leading clergy.

But the Macedonian Apostolic Church, even if illegally spoiled (as the Turkish Sultan had no ecclesiastic authority whatsoever over the autocephalous church institutions) from the administrative jurisdiction over its eparchies – didn’t perish. It continued to perform the holy apostolic teachings among its Macedonian flock without hesitation. Macedonian clergy organized itself in local Church Schools, outside of the schismatic Ecumenical Patriarchate reach. The difficult economic situation in that moment compelled the Ohrid archbishops and their bishops to turn to Europe and from there to seek financial assistance. This harsh situation of the Macedonian people, as well as the Ohrid Archiepiscopacy, continued until the end of 18th century.

This and other circumstances reflected on the financial and general situation of the Macedonian Archdiocese. After the illegal administrative abolition of Ohrid Archiepiscopacy, the Ecumenical Patriarchate had initially removed the ecclesiastic jurisdiction from the indigenous Macedonian episcopes, they then were replaced by foreign “Phanariot” bishops from Istanbul, who were not accepted by the local people, as they didn’t speak the language of the flock they were given. First they banned the Macedonic liturgy and worship in Macedonian cities where they were appointed. Further, these bishops used their authority not only to collect the church taxes and get rich, but also to use their power for political and other purposes.

Phanariots: were members of prominent Greek families in Phanar, the chief Greek quarter of Constantinople where the Ecumenical Patriarchate is located. They emerged as a class of moneyed Greek merchants (of mostly noble Byzantine descent) during the second half of the 16th century, and were influential in the administration of the Ottoman Empire’s Balkan domains in the 18th century. The Phanariots usually built their houses in the Phanar quarter to be near the court of the Patriarch, who (under the Ottoman millet system) was recognized as the spiritual and secular head (millet-bashi) of the Orthodox subjects—the Rum Millet, or “Roman nation” of the empire, except those under the spiritual care of the patriarchs of Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Ohrid and Peć. They dominated the administration of the patriarchate, often intervening in the selection of hierarchs (including the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople). It is under the Ottoman millet system after 1767, that the Phanariots gained a great deal of wealth by illegally attaining control of the treasuries from all the Orthodox eparchies in the Balkans.

The whole ecclesiastic structure in Macedonia was in serious danger. Rebellion and strong protests was justified in the eyes of Macedonian believers. In order to preserve the Macedonian Apostolic Church, its millennial traditions and institutions, they organized themselves in local Municipal Church Communities and Church Literacy Schools across Macedonia, and openly refused the abusive agents of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Therefore, the Macedonian people under the guide of its own priests, appointed directly by the people, saved their very own Macedonian Apostolic Church from total disaster. Holy artifacts and books in Old Church Macedonic were meticulously copied and preserved for future generations by common people. Deacons and priests chosen by these Church Commities continued the holy service in the Macedonic language and rite, professing the original Apostolic teachings just like during the epoch of Bogomils centuries ago. They transcribed, lectured, and transmitted the Holy Macedonic Gospels and Liturgy across the Macedonian Peninsula despite all the forms of mistreatment and persecution used by the church institutions and Phanariots of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul.

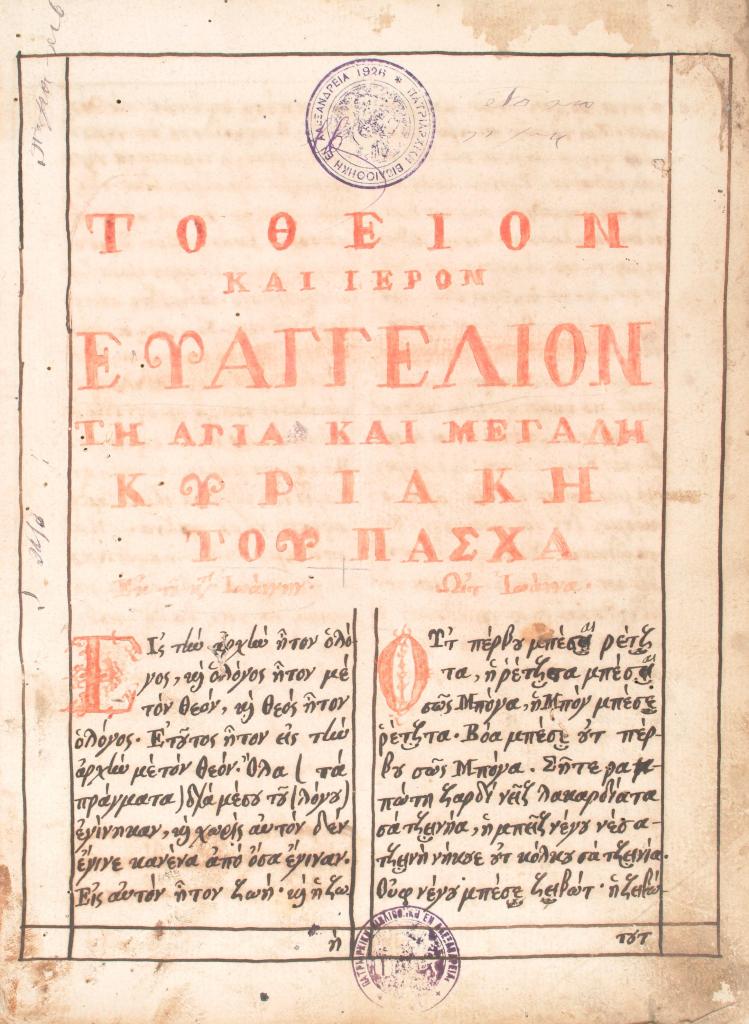

Konikovo Gospel Manuscript

One magnificent example of this painstaking and incessant ecclesiastic struggle and holy work of the Macedonian Apostolic Church preachers in this period, in circumstances of illegality, is the Konikovo Gospel manuscript. Written somewhere at the end of 18th century, and rediscovered by the Finnish historian and philologist Mika Hakkarainen in the Library of the Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria in 2003, the Konikovo Gospel represents an extraordinary example and one of the many holy literacy monuments of Macedonic rite.

It is an exceptional testimony of the enormous spiritual dedication and sacrifice of the Macedonian Apostolic Church priests, deacons and religious followers. It is a hand-written manuscript of vernacular Macedonian written using Greek script, in what is known as the Macedonic dialect of Lower Vardar. Written by an unknown author, and grammatically redacted by the hieromonk Pavel (i.e. deacon Paul) Božigropski, a protosingel of the Holy Sepulchre Church in the village of Konikovo – Voden/Edessa eparchy in Aegean Macedonia.

It is in fact the oldest known text that directly reflects the living Macedonic dialects of what is today Greek Macedonia and also the oldest known Gospel translation in what is known as Modern Macedonian. Nevertheless, it confirms the uninterrupted millennial continuity and constant lineage of the apostolic teachings and traditions of the Macedonian Apostolic Church – through the Macedonian language and liturgy, from the times of Apostle Paul till today. Cyril and Methodius used the living Slavonic dialect of the Thessaloniki region in their translations in the 9th century. The Konikovo Gospel represents a specific phenomenon in the course of historical development which today includes a distinct Macedonian national identity, the most important element of which, it can be argued, is precisely language.

Macedonians Moving to Cities (1700 – 1800)

In the eighteenth century people in all of the Balkans started moving into cities once again. The influx of Christian peasants into cities altered the ethnic and social structure of Balkan cities. As a result of trade with the outside world and the increase in the number of guilds (esnaf), cities became avenues through which Western influence was diffused in the Ottoman Empire. In addition to imports of foreign goods, occasional Western travellers visited the Ottoman cities. The styles and vogues of Istanbul set the tone for city life which then permeated into towns and villages that were closest to these centres. Zelenic-Sklithro was one of those villages that benefited from this economic and cultural expansion due to its location. Being located on a road connecting Kastoria via Kleissoura and Florina via Sourovic (Amyndaio) it had access to the major urban centres of the region and beyond.

Thus we have the start of men – Pechalbari – moving to urban areas for work. The migrant could be away for months or even years at a time. The purely seasonal workers were usually builders, carpenters, metal-workers, and the like, who carried their essential tools with them. They would leave home usually on St. George’s day (23 April) to return on the day of St. Demetrius (26 October) or at Christmas. The women and children with the old folk would escort them for a certain distance outside the villlage or town, imparting suitable and good wishes. Those who stayed away for many years usually returned after making their fortunes, which could be anything between five and twenty years.

Ottoman Influence on Zelenic-Sklithro

Ottoman influence in the Balkans was much greater in urban centres than in mountainous and inaccessible regions.The Ottomans did not assimilate the indigenous cultures but instead refreshed earlier oriental influences and added their own flavour to them. Ottoman influence is apparent in dress, crafts, arts, and diet. The celebrations, including weddings, are accompanied by profuse Turko-Arabic terminology. The borrowings from the Turkish lexicon are enormous, especially in the domain of food, agriculture, livestock, mining, crafts, trade, home furnishings, tools, and social customs. The words of Turko-Arabic and Persian origin have entered the vernacular of the Christian subjects so deeply that the Balkan people, for example, unconsciously create terms based on Turkish word-roots. Even the person who made the pilgrimage to Jerusalem was honoured with the Islamic “Hadjj.”

The Hadjj and Zelenic-Sklithro

One of the first two clans in the village of Zelenic was named Ovci. Someone in the clan visited Jerusalem and was baptized in the River Jordan. As a result, they earned the title, Hadj in front of their name, resulting in Hadjiovci. This was copied from the Hadj, an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. This clan or individual would have had to have enough funds (wealth) to be able to travel such a distance and back from the Holy Land. We can assume that trade in the village (2 bazaars per week) would have increased the standard of living for some families/clans.

Macedonian (Zelenic) Influence onto the (Yoruk) Turkish Muslims

The Balkan Muslims and those in Zelenic (as per oral history) had taken into their religion many pagan and Christian practices and beliefs. Some continue to honour the saints of their family even today, two generations after the Turko-Greek population exchange of 1923. In Zelenic, they celebrated the Christian St. George. The Muslims and Christians in the Balkans and especially in Zelenic, exchanged visits on Bayram (festival or celebration) and Christmas. Belief in miracles, superstition, and fortunetelling were extensive among both. Even though Ottoman society had its roots in local Anatolian, Muslim and Turkish sources, as time passed it absorbed elements of the other cultures. The Balkan influence was a result of protracted cohabitation of the Anatolian nomads (Yoruks), with not only the people of the Balkans, but also the local geography, economy and the religion and customs of the population.

The Macedonian Village

The village served as the main reservoir of human and material resources. By living in compact isolated settlements, with their own social organization, the peasants were able to resist the penetration of alien cultures and to preserve their ethnic individuality. This perpetuated oral tradition and remembrances of medieval independence and glory. The peasants were the backbone of the insurrectionist movements against Turkish rule. The degree of Ottoman influence on the village and the conditions of peasant life were determined in part by the forms of social organization of the particular community, the proximity of the Ottoman landlord and official, access to the important roads, density of the Christian population, and by the whims of the Turkish authorities. Some peasants (villages) were less oppressed than others, but as a rule, Christian peasants paid higher taxes than their Muslim counterparts. This was the case in Zelenic, as the village was also settled by Yuruk nomads from Anatolia.

The identity of peasants was mostly quite local since social conditions were such that the Macedonian peasants in the Balkans lived in relatively small political subsystems. They lived in a kind of a Neolithic age until at least the mid-nineteenth century, and some of these Neolithic features survived even later. These characteristics have been identified as the so-called Earth Culture. The culture of these people is said to have been bound religiously, psychologically, and economically to the soil and space around him.

The ancient pagan rituals and conceptions survived in Macedonia and were fully present and obvious to some Western travellers who visited European Turkey. The religious cult of the inhabitants of Zelenic and Macedonia occupied a key place in their daily lives. In this cult, the hearth played an important role in creating the existence of stable habitations. Milorad Ekmečić termed this religious division among the South Slavs as the epoch of “the era of beliefs” (1790 – 1830).

In spite of the abolition of the autocephalous Macedonian Apostolic Church in 1767, the superstitions and relics of paganism, made the Greek Ecumenical Patriarchate harder to penetrate the beliefs of the Macedonian people. Their superstition was stronger than the official Greek Orthodox Church and its teachings. More on this topic (Rituals and beliefs) can be found in the 1900s History Section with the travels of H.N. Brailsford, Macedonia, Its Races and their Future and in the Religious Ritual Section

Characteristic of Zelenic-Sklithro during the 18th Century:

- The Yoruk nomads did not constitute a ruling element therefore Christians preserved their identity and customs;

- Each group remained a legal entity – socially exclusive and culturally self contained;

- The Christians lived on the northern side- quarter (mahalle) of the Lehovo (Eleovo) and Asprogia (Strebano) creeks, and the Muslims lived south of these two creeks;

- The Muslims as oral history states, did not own any land but worked for the Christians;

- Christians and Muslims lobbied the authorities not to turn the village into Chiflik and to pay lower taxes due to the peaceful cohabitation between the Christians and the Muslims;

- The village was at the frontier of the mountanous regions and had access the the urban centres in the Bitola-Kozani corridor;

- The villagers (Christian and Muslim) payed a poll tax (cizye), land tax (harac) and various othe dues and fees, including the church tax, which went to the Archbishop in Ohrid, but after 1767 it was collected by the Greek Bishop in Kastoria (Kostur) and the Patriarch in Istanbul;

- The peasants of Zelenic-Sklithro were less oppressed due to their peaceful cohabitation with the Yoruk Turks, but, as a rule, Christian peasants paid higher taxes than their Muslim counterparts. This was not the case in Zelenic-Sklithro;

- By living together in hearths, the joint family secured economic advantages in labour power and lower taxes. This encouraged people to band together under a single roof;

- This contributed to the preservation of the Zelenic Macedonian ethnic and cultural individuality

- With the expansion of trade in this period, the number of villagers moving to urban centres increased.

1768 – 1774 Russo-Turkish War

Throughout the Monastir region preparations to support the war effort were being made with the call of all “Sipahis” (cavalry corps) to arms. During the war, Albanians took advantage of the disorder to acquire a considerable amount of power and as a result, life was made very difficult for the Christian inhabitants in western Macedonia. Turko-Albanians plundered the region forcing Vlach-speaking villages to migrate to the interior of Macedonian. They moved to place such as Neveska (Nymphao), Klissoura, Blatsi (Oxyes), Hrupista (Argos Orestiko), originally inhabited by Macedonians. The Vlach-speaking settlers were mainly merchants in woollen articles, tailors and gold-smiths. But there were many who continued their former nomadic way of life to even as late as the second world war.

The domination of the countryside by the Albanians, coupled with a general spread of brigandage (lawlessness), this forced inhabitants of some western Macedonian villages to migrate to quieter surroundings. One of those villages was Aetos who moved to Florina (Lerin). However the complaints of the Zaims and Sipahis (military officers) led the Sultan to order the return of those people to their native villages. Even though the village Aetos is 6.5 km from Zelenic, there is no mention of the inhabitants of Zelenic being attached but this may have been attributed to the fact that the village was occupied by both Christians and Muslims.

Despite the termination of the Russo-Turkish war in 1774, peace was not restored in the interior of Macedonia. On the contrary, Albanian mercenaries, who had gone into the Peloponnese to put down the Greek insurrection, created such a reign of terror in the Greek inhabited areas of the Peloponnese and brought such misery to Macedonian and Turkish populations alike, as these forces travelled back to Macedonia in the north.

Ali Pasha and Macedonia

As the 18th century came to a close, almost half of Macedonia had gone out of cultivation. After a long period of drought, the threat of famine and a noticeable increase in robbery, the inhabitants were at the mercy of the lawlessness that had erupted. Thus on 7 June 1794 the Venetian consul writes: “…in addition to a shortage of foodstuffs we now have a further scourge… We are surrounded with numerous bands of robbers who plunder everybody without distinction and lay waste the rural areas… No more provisions are being brought into the district as a result of this veritable reign of terror provoked by the robbers… There is a singular absence of provisions… the populace is troubled…” The brigands overran the kazas of Ostrovo, Florina, Edessa and Sari Gol (Zelenic region) and plundered travellers passing through the region.

Throughout this stormy period the inhabitants of Macedonia lived and worked within a close framework of community and guild organization, having close ties with what churches and monasteries had survived. The peasantry of the rural areas were continually being exploited by the Moslem beys (ranking leaders of their ommunity), and the renegades amongst them were often the worst offenders. To this was added the insecurity created by the frequent incursions of marauding bands of Albanian brigands, with various beys at their head. These incursions became particularly serious after the Orlov operations, when large numbers of Albanian troops marched south to quell insurrection throughout the Peloponnese. The Albanians perpetrated daily every kind of outrage. They had become in every sense of the word masters of the Greek lands, and in Greek history this period is commonly termed ἀρβανιτοκρατία (arvanitokratia – Albanian Rule).

The Orlov Revolt (1770) was a precursor to the Greek War of Independence (1821), which saw a Greek uprising in the Peloponnese at the instigation of Count Orlov, commander of the Russian Naval Forces of the Russo-Turkish War. The revolt failed to spread to the rest of Greece (Morea – Peloponnese).

This period of anarchy saw the rise of Ali Pasha of Yannina, who controlled much of Epirus, Western Macedonia and Thessaly. During the 34 years that Ali Pasha was supreme master in those parts, it was the Christians who bore the brunt of his tyrannical behaviour. It is not, therefore, surprising that in the midst of such endless suffering, the inhabitants of many Western Macedonian villages went over in despair to Islam. Known as the Lion of Yannina, he was an Ottoman Albanian ruler who served as pasha of a large part of western Rumelia, the Ottoman Empire’s European territories. Originally, he was a brigand who ravaged Epirus, Thessaly and Greek Macedonia. After joining the administrative-military apparatus of the Ottoman Empire and, holding various posts until 1788, he was appointed pasha, ruler of the sanjak of Ioannina. As ruler of the region, he continued his banditry and looting which drew the attention of the Sultan who declared him a rebel.

Sources:

- Anscombe, F. F. (2006). The Ottoman Balkans, 1750-1830. Markus Wiener Pub.

- Bozigropski, P. (1871). [Page of book]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Konikovo_Gospel_01.jpg

- Chulev, B.Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/33684908/Macedonian_Apostolic_Church_-_Ohrid_Archiepiscopacy.pdf

- Chisholm, H. (1911). Phanariotes. Retrieved from https://www.wikizero.com/en/Phanariotes

- Fielder, G. E. (2010). Jouko Lindstedt, Ljudmil Spasov, and Juhani Nuorluoto (eds.). The Konikovo Gospel/Кониковско евангелие: Bibl. Patr. Alex. 268. Scando-Slavica, 56(1), 123–125. doi: 10.1080/00806765.2010.483781

- Giannelli, C. (1958). Ciro Giannelli, “Lexicon of the Macedonian Language” , 16th century. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/1107169/Ciro_Giannelli_Lexicon_of_the_Macedonian_Language_16th_century

- Karpat, K. H. (1985). Ottoman Population, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Kitromilides, P. M. (1999). Orthodox culture and collective identity in the ottoman balkans during the eighteenth century. Bulletin of the Centre for Asia Minor Studies, 12, 81. doi:10.12681/deltiokms.76

- Markovich, S. (2013). Patterns of national identity development among the Balkan orthodox Christians during the nineteenth century. Balcanica, (44), 209-254. doi:10.2298/balc1344209m

- Schallert, J. (2011, September 16). The Konikovo Gospel: Konikovsko evangelie (review). Retrieved February 10, 2020, from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/449671

- Schallert, J. (2011). [Review of the book The Konikovo Gospel: Konikovsko evangelie]. Journal of Slavic Linguistics 19(1), 131-152. doi:10.1353/jsl.2011.0016.

- Sowards, S. (1999, June 14). Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History. Retrieved from http://staff.lib.msu.edu/sowards/balkan/

- Todorov, N., & Todorov, N. T. (1983). The Balkan City, 1400–1900. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

- Unknown. (1900). Fanarion, Greek district in Constantinople [Photograph]. Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/96/Fanarion.jpg

- Vakalopoulos, A. E. (1973). History of Macedonia, 1354-1833. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies.

- Vucinich, W. S. (1962). The Nature of Balkan Society Under Ottoman Rule. Slavic Review, 21(4), 597-616. doi:10.2307/3000575