In 1481 as the Ottoman officials were registering the village of Neveska (Nymfaio), they noticed smoke at various points in the valley below. When they inquired, they were told about the inhabitants of the village of Zelenic. These officials, then proceeded to register the village using the defter tax register. It recorded names and property/land ownership; it categorized households, and sometimes as in the case of Zelenic, whole villages, by religion. The names in defters can give valuable information about ethnic background; and these tax records are a valuable source for current-day historians investigating the ethnic & religious history of the Ottoman Empire.

By 1481 Bayezid came to the throne and to finance his undertakings he had increased customs duties and some of the taxes paid by peasant farmers. This is the year in which Ottoman officials were scouring the countryside and mountain regions of Macedonia to register new tax revenue. As a result, he brought some twenty thousand villages and farms under state control and distributed them as Timars. (a fief with an annual value of less than twenty thousand akces, whose revenues were held in return for military service).

The primary role of the Timar system was to collect feudal obligations, before cash taxes became dominant. In the Balkans, peasants on timars typically paid a tithe or a tax in kind, of around 10–25% of their farm produce. This system closely resembles the medieval Macedonian feudal system, which in turn was inherited from the Byzantine.

As the Ottoman Empire conquered new territories, it adopted and adapted the existing tax systems already used by the previous governments. This led to a complex patchwork of different taxes in different parts of the empire, and between different communities.

A patchwork of different communities and taxes applied to different religious and ethnic groups. In some cases, local taxes were imposed on non-Muslims specifically to encourage conversion, conversely, measures might be taken at other times to prevent conversion, in order to prop up tax revenues.

There was a practice of making villages communally responsible for the tax; if one villager fled (or converted to Islam), the others would have to pay more. In good years, community pressure would ensure compliance; but in bad years the difficulty of paying a share of other people’s taxes could lead to a vicious circle, as more taxpayers fled.

In the Balkans, Vlachs had tax concessions under Byzantine and Macedonian rulers in return for military service, and this continued under the Ottoman. There was a special vlach tax, rusum-e eflak: one sheep and one lamb from each household on St Georges day each year. Because Vlachs were taxed differently, they were listed differently in defters. This was the case for the village of Neveska (Nymfaio) as the original Macedonian inhabitants were overtaken by Vlach settlers.

The protection of the peasantry as a source of tax revenue was a traditional policy which encouraged an attitude of tolerance. In essence, this was a continuation of the Byzantine Empire tax system, but now with a different landlord. Income from the poll tax (harac) formed a large part of Ottoman state revenue.

By 1495 the Ottoman Empire began to play a part in European politics and by the end of the sixteenth century the Ottoman waged a series of wars against the Persians in the east, the Habsburg in Central Europe and the Portuguese on the Indian Ocean. War put enormous pressure on the Ottoman finances. Taxes were often difficult to collect, especially from rebellious areas. Conversely, high taxes could often provoke rebellion. The demand for taxes was higher during times of war; these factors together could provoke a vicious circle of taxation and rebellion

The two institutions of the Ottoman Empire were the slave and timar systems. They defined the state’s military and political order, the taxation system and forms of land tenure, determining its whole social and political structure. Towards the end of the sixteenth century these institutions began to deteriorate. These timars were held by a sipahi – a cavalryman holding a timar in the provinces in return for military service.

The timar-holding calvary, armed with the traditional mediaeval weapons – bow and arrow, sword and shield – formed a mediaeval army who’s usefulness was gone when it met the German infantry equipped with firearms. This cavalry regarded itself as forming a true military class in the mediaeval tradition and considered the use of firearms unbecoming to their sense of chivalry. The Ottoman government, therefore, sought other ways of creating an army capable of competing with the German infantry

Due to the changing nature of warfare with the equipping of infantry with firearms, less and less sipahis were used in the service of the Ottoman military. The sipahi army was now mostly used only for building roads and fortifications. Some of these sipahis may have settled in Zelenic after 1481 (the date of the register for the village in the Ottoman defter). These changes in the classical military organizations, which had once held such an important place in the empire, had a profound effect on its political, economic, and social life.

To meet the new financial demands on the empire, some lands assigned a timars were brought under direct Treasury control and the right to collect their revenue farmed out, to sipahis. They did not own the land, but they owned to right to collect the taxes in the form of products produced for the sultan, while keeping a portion for their livelihood.

The military campaigns of the Ottoman reached their climax in the sixteenth century which caused a huge deficit in the state budget. The government increased taxes but revenue was insufficient. By 1576 money taxes became the principal source of state revenue, but taxation was a heavy burden on the peoples of the empire, especially on its Christian subjects, and discontent was widespread.

These measures had disastrous results, as provincial governors (Beylerbeyis) were granted authority to raise local taxes to pay for the enlistment of provincial militia (sekban) began to plunder the people on their own account.

These governors used their influence and power to amass great fortunes. They acquired large tracts of lands and the villagers on these lands sank to the status of share-croppers. As the central authority weakened in the provinces, their power and influence increased, and it was this class which was to provide many of the local dynasties which later appeared to dominate the provinces in the eighteenth century.

Against the mercantilist economics of contemporary European powers, Ottoman statesmen clung to the policy of free markets, their main concern being to provide the home market with an abundance of necessary commodities. They never fully broke away from the values and outlook of near-east culture, while closing their eyes to the outside world.

Even though Zelenic was first registered in 1481, the people and the valley were not ripe for being exploited. The settlement of Zelenic must have gone through some up-heaving times, first with the arrival of Muslim settlers into their valley. They may have been first with the Yoruk nomads and later joined by retired Sipahis. Being most likely armed, they forced the Christian inhabitants of Zelenic out of their homes and onto the northwestern side of the village.

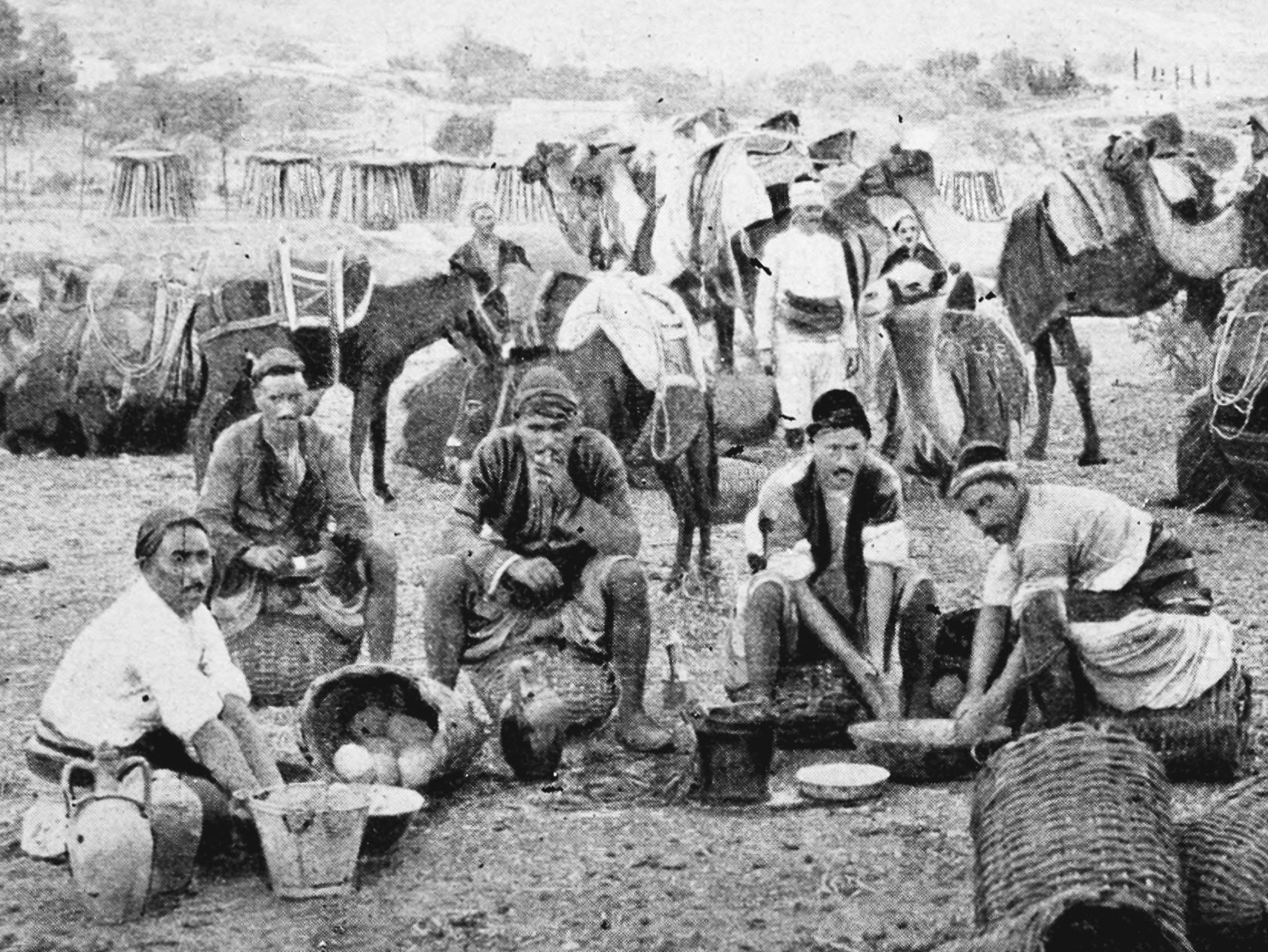

The Yoruk were a Turkish ethnic subgroup whom were nomadic, primarily inhabiting the mountains of the Balkan peninsula. The Kailar Turks formerly inhabited parts of Thessaly and Macedonia (especially near the town of Kozani and modern Ptolemaida). Large numbers of nomad shepherds, or Yörüks, from the district of Konya, in Asia Minor, had settled in Macedonia. Further immigration from this region took place from time to time up to the middle of the 18th century. After the establishment of the feudal system in 1397 many of the Seljuk noble families came over from Asia Minor; some of the beys or Muslim landowners in southern Macedonia before the Balkan Wars may have been their descendants.

Far from the main lines of communication, Zelenic provided a wonderful natural retreat for the persecuted inhabitants. Cut off from the rest of civilization by the rugged and forested massifs, the area became a refuge for the inhabitants. At the same time, these forests impeded immigration or dispersal, so that the old families who had fled for shelter remained unmixed with outside elements, thus preserving the purity of their stock. Consequently, the people of Zelenic remained proud of their Macedonian descent.

The 1500s must have brought uncertainty and cautious optimism at the same time. The uncertainty of constantly being on guard created an environment of “fight or flight.” As the new homes were built side-by-side with adjoining walls and secrete doorways leading from one home to the other. In this way, Christians could escape or even move food and goods from one home to the other, hiding their possessions from being taken.

Once Muslims realized that their chances of survival depended on their Christian neighbours’ ability to provide for their kin, hostilities lessened, and both groups could focus their energies on further clearing the valley for agriculture. A degree of safety resulted in an increase in the population through procreation and the influx of more people into the valley of Zelenic. Many of the toponyms (area names) originated from those earlier times with the clearing of the valley. You can refer to the maps section on toponyms to see those locations. These include names such as:

- Izvoro – fresh water spring above village north side

- Dolnite Levada – fields above highway (lower fields)

- Gornite Levada – fields above dolnite fields

- Shinekopatch – fields below highway

- Morva – from Gogadana’s house to shinekopatch

- Poprija – bend of highway after Strebano

- Shiroka Levadia – wide fields

- Sphirtsivitch – on other side of river which comes down from Strebano

- Eleoftska reka – Lehovo river

- Tsarn Kamen – (Black Rock) can see Lehovo from this rock

- Keramnitsa – from Eloftska reka to village

- Gradishta – mountain above Pine trees behind village

- Suligrop – Where Suli (Yoruk) was barried

- Toombata – (Hill) towards Agrapedias gov’t dug tunnel for hydro dam

- Yame – below Toombata north side of river after former Yotis residence

- Blato – after Toombadta on south side of river

- Klissoura – between to Toombata (hill) and north mountain

- Tsrna Voda – before pass between hill (south) and mountain (north)

- Vodanitsa – Toomba on south side use to have a mill the opposite side of Gorichko (Agrapethias)

- Gorichko – village after vodanitsa – going east on road

- Banja – Old natural spring

- Sebalci – old location of Zeneniche above the ancient bath

- Sveta Petka – small chapel on north side

To view a map with all the toponym, refer to the Menu on Maps.

The influx of Jews into Macedonia was to play a key role in further increasing the population. Towards the close of the 15th century, successive waves of Jews arrived at the harbour of Thessalonica (Solun). First were the Ashkenazim who were expelled from Bavaria in 1470. However, the largest contingent the Sephardic came from Spain between 1481-1512. The Turkish Sultans adopted a hospitable attitude towards the new Jewish immigrants, as they resettled them throughout western Macedonia. Cities such as Ptolemaida, Kastoria, Florina, Veroia, Naousa, Bitola, Ohrid, Struga and Skopje had a large influx of Spanish Jewish immigrants. There was no mention of Jewish settlers in Zelenic, but with the clearing of the valley and the expansion of agricultural production, the village became prosperous and more well known. Certainly, village inhabitants would have traveled to the larger towns and cities the either work, buy and/or trade goods. They would have had some type of exchanges with Jewish merchants in these urban areas. One thing we do know, is that some decedents of Zelenic who have done their DNA test, show evidence of Jewish background.

As a result of the influx of Jewish settlers into the towns and cities of Macedonia, the impoverished Christian peoples were beginning to return to old or new commercial centres. This coincided with the increase in trade and travel, following the discovery of the new world. More and more goods began to enter the region as farmers were introduced to new varieties of crops. Villagers hiding in the mountainous regions around Kastoria (Kostur), Florina (Lerin), and Bitola (Monastir), began to venture out into these urban centre for work and trade.

The discovery of a 16th century old Lexicon at the Archivum Secretum Vaticanum, the secret Vatican Library in the late 1940’s is another example of the millennial continuity. It is written using the Greek alphabet and it was thought for some time that it was a Greek language. However it could not be deciphered using Greek, and when read out it was discovered that the Language was Macedonian relating to the Old Kostur (Kastoria) Dialect from the Aegean Macedonia – Northern Greece. Two University professors Ciro Giannelli, Andre Vaillant have written a book on the subject dated 1954 “Un Lexique Macedonien Du XVI Siecle. This book presents solid proof that the Macedonian Language had existed for many centuries prior to the creation of the Modern independent State of (North) Macedonia .

Sources:

- Giannelli, C. (1958). Ciro Giannelli, “Lexicon of the Macedonian Language” , 16th century. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/1107169/Ciro_Giannelli_Lexicon_of_the_Macedonian_Language_16th_century

- Inalcik, H. (1973). The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300-1660.

- Batzaria. (2005). Retrieved from http:/https://www.wikizero.com/en/File:Yoruk-map.gif

- Peev, K. (2013, October 22). Giannelli’s Macedonian Dictionary from the 16th century. Retrieved from http://macedonianhistory.ca/news/lexocon_notes.pdf

- Picasa. (2017). Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/48/Ottoman_Sipahi%2C_Melchior_Lorch_%281646%29.jpg

- Unknown. (1893). Retrieved from https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f3/PSM_V43_D200_Yuruk_encampment.jpg

- Vakalopoulos, A. E. (1973). History of Macedonia, 1354-1833. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies.