In the last years of the 14th century almost all of Macedonia had fallen under Turkish rule, and in 1408 Turks had taken over the Holy See of the autocephalous Macedonian Apostolic Church. Ohrid found itself under the Turkish yoke. Nevertheless, the Turks respected the Macedonian Holy See and its apostolic Christian authority. And despite this new foreign occupation the Macedonian Apostolic Church expanded its jurisdiction. However it suffered great material damage from the Turks as the conquest of Macedonia was accompanied by the devastation of towns and villages and looting of Christian properties. Due to the displacement of the population, episcopacies lost revenue and they became impoverished. There was a massive Islamization of the Macedonians, as whole villages converted to Islam.

Many Macedonians took flight into the mountains and remote parts of the interior to avoid conversion to Islam and because of the persecution by the Ottomans. With the exception of larger towns and cities (Salonica 1430) which provided some safety were the last to fall under the conqueror’s yoke. The relations between the Macedonian Apostolic Church – Ohrid Archiepiscopacy and the Constantinople Ecumenical Patriarchy worsened in 1439, when the Constantinople Patriarchy entered into a union with the Roman-Catholic church.

Skanderbeg

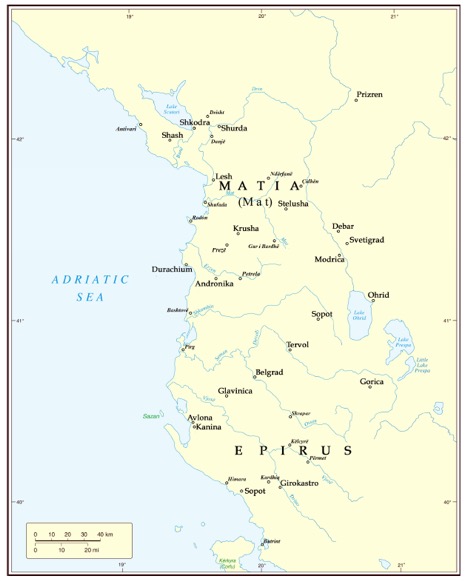

Nevertheless, the 15th century still saw many Macedonians fighting fiercely and rebelling for freedom from Turkish tyranny. One of these was the mountainous Macedonian principality of Mat (or Matia) and Debar, in Western Macedonia and what is today northern Albania, ruled by George “Skanderbeg” Kastriot. These isolated lands were resisting successfully the Ottoman raids for so long thanks also to the financial and material support which they continuously received from their allies across the Adriatic Sea, namely, the Spanish Aragon, Venetians, Ragusans, and the Pope.

After many failed Ottoman incursions in western Macedonia, the Sultan Murat II decided to march a large army into Skanderbeg’s dominions, in order to capture one of the key Macedonian strongholds, the fortress of Svetigrad. This city was one of the last Macedonian strongholds and a bastion of Christianity in western Macedonia. Its very name underlines that fact – “Svetigrad” means the ‘Holycity’ or “Saint-city” in plain Macedonian. This city was most probably ubiquitous to what was known as a strong fortress from the ancient times under the name of ‘Uscana’, a place where the last

Macedonian king from the Argead Dynasty of Macedon, Persei (Lat. Perseus), won a great victory against the invading Romans in 170 BCE. Uscana, now renamed into ‘Svetigrad’, was again a Macedonian stronghold in front of foreign invaders, this time against the Ottoman hordes from the east.

Born in a Christian Macedonian family, as a kid he was recruited in the dreaded Janičari Corps (Turkish: “Yani-čari” – ‘Young troops’). After a brilliant military career, and after exerting even a diplomatic function in the Russo-Turkish negotiations, at some point he deserted from the Turkish army and returned to his family in Matia. This was due to his national awakening, while he was participating as a Macedonian translator in the Russo-Turkish negotiations. He was impressed by the grandeur and power of the Russian state, which bothered him, as a Macedonian in service of his own occupier. Thus, he deserted and decided instead to fight his former masters, the Ottoman foreigners that usurped his homeland. From then on he fought the Turks fearlessly and with so much ardor that in his time he earned the nickname “Skander-beg” – ‘Alexander-lord’, as the Turks called him because of the stunning vehemence and fierce boldness of his attacks with which he terrorized them. According to the Turks, Skanderbeg’s military stratagems were comparable only to one other Macedonian – Alexander the Great.

On July 31, 1448, after two and a half months under siege, the garrison of Svetigrad surrendered. For the next 20 years the Ottoman tried but did not succeed to take Skanderbeg’s stronghold Krusa. Since no conventional weapons seemed to be able to kill him, Skanderbeg himself, same as his predecessor Alexander the Great, died of malaria in the then Venetian stronghold of Lissus (Lesh) in 1468. The Macedonians were left to their own devices and were gradually subdued by the Turks over the next decade. After Skanderbeg died and after 25 years of continuous Ottoman invasion the principality of Matia fell under Ottoman rule.

Byzantium and its holy capital Constantinople managed to withstand the Ottoman attacks until 1453, and there after, gradually conquered one by one those small Macedonic kingdoms that were left in Western Macedonia. By 1479, all the conquests of Sultan Mehmed in Macedonia were fulfilled.

Zelenic

The forested massifs of Macedonia offered protection to the neighbouring populations of the Pintus, Grammos, Vermion, Pieria, Olympus, Hasia , etc.. Life was very difficult at first as people had to forage for food and find water. Once they found a suitable site they would cut down the forest of oak and pine and build their homes and village. This is how the inhabitants of Sebatci, abandoned their town and formed the new village of Zelenic.

The location of the Zelenic area was defined by the economic conditions, particularly soil and climate, and this defined their terms of livelihood. According to oral history, the inhabitants named the village Zelenic because the valley was green (zelen in Macedonian is green), and fertile for farming but trees, shrubs and vegetation had to be cleared. Life must have been very difficult, almost to the point of malnutrition and they were forced to turn to herding while more and more land was being cleared.

Life must have been indescribably hard for these people in the winter time when all growth had died down and they found themselves completely cut off by snow from the outside world. Ample stores of wood and food would be imperative for survival. They were in an endless struggle with the elements and only the hardiest amongst them could have won through.

In such circumstances, Western Macedonians who had taken to the mountains were driven to exploit whatever form of livelihood the surroundings permitted. The two chief occupations were herding and the manufacture of wool and woolen goods. The inhabitants of Zelenic were lucky to also have agriculture as they happened to be located in a valley surrounded my mountains, with plenty of fresh water for drinking and irrigation.

Unfortunately, flight to the mountain massifs and valleys brought to the refugees no more than temporary relief from the Ottoman yoke. Once they had consolidated their conquests and had firmly established themselves throughout Macedonian lands, the Ottoman made life increasingly difficult for the mountain dwellers. It was not long before they had finished off the half completed work of their forefathers, that their refuge became known.

The first documented evidence appears when Zelenic is first mentioned in an Ottoman defter (tax register) of 1481. The majority of the villages in the Macedonian mountain regions came into existence this way. Revolts and uprisings took place and the besieged “reaya” (enslaved population) had to leave their homes, and hide in safe places which were in the mountains.

According to the oral history passed on by our grandfathers, when the Ottoman had reached the limit of taxing the Christians in the plains and valleys, they turned to the mountains beside the plains. Aetos (Ajtos), and Agrapidies (Goricko) were first to be registered, and as the Ottoman administrators and soldiers reached Nymfeo (Neveska) at the top of the mountain, they saw smoke in the valley below. They then proceeded to Zelenic (Sklithro) and registered the village as they did with the other villages, so as to increase their sources of revenue from the Christians.

Some villages had exemptions or lower taxes if they were along the main routes and had the task of constructing and maintaining roads. The village of Nymfeo (Neveska) was originally inhabited by Macedonians who had fled Sebalci (4-5 families). Years later, the village had an influx of Vlachs (Christian nomads of Macedonia) who were exempt from certain taxes in return for service as frontier guards and raiders. The Ottoman usually moved Vlachs on mountain tops to keep an eye on the Macedonians in the valleys below. Since the village was on the mountain top, they acted as frontier guards (policemen) in the area.

As the decades went by, more and more of the land was cleared for farming and by the time Zelenic was discovered by the Ottoman, the valley and people were ripe for being exploited. The valley was soon inundated with most likely wondering Yoruks. The villagers were forced to move on the western side of the Eleovo (Lehovo) creek. As the Muslims claimed the original site for themselves. They now also had to pay a tax as a result of being registered.

Timar System of Agriculture: The economy of the Ottoman Empire was mainly based on farming using the timar system. The longevity of the Ottoman Empire was mostly dependent on its economic and military systems. Timar was one of these systems that addressed both the economy and the military of the Empire.

It was not possible for the Central Government to manage all the lands owned by the Ottoman Empire. Not only, it would require a lot of organization, but it would also be an inefficient way of working the land. Therefore the government gave (or loaned) land to certain people. These people were called reaya (tax paying subjects) and were expected to work the land and pay a certain amount of their income as tax. This system was used for land in the plains, but land that was in marginal areas that were mountainous and forested were treated differently. As the empire expanded and more revenue was needed, the free and independent people hidden in the forests and mountains were being discovered and government officials began a process of registering these lands as property of the state.

The government began to exchange the right to collect the tax given by the reaya, in return for certain services, preferably military. The people who were given this privilege were Muslims called timariots (timar holders). These tax collectors did not own the land, and the reaya were not their slaves. Instead of land, they owned the rights to collect the taxes, and in exchange for this income, they had to support the army with a number of cavalrymen, called the sipahis. The number of troops they needed to supply depended on the amount of income the timars provided. As a result of this system, the Government was able to efficiently manage the economy, and call upon an army of timarli sipahi’s when needed.

The following information is the first documented census of Zelenic. It is the Ottoman census of 1481 and it itemizes the agricultural production of the village and the names of the male inhabitants. The village had the option of avoiding military service by paying a yearly tax according to the value of their agricultural output. According to this census, the village was already split between Christians and Muslims. This indicates that the Yoruk Turks were in the village before the 1481 census, earlier than previously thought.

Turkish Documents for the History of the Macedonian People: General Census Defter from the XV (15th) Century – 1481

Names of the males was for the purpose of military service in the Ottoman army.

Todor, the son of Kondo; Dimko, son of Kondo; Dimitri, the son of Mare; Miho, his son; Rajko, the son of Dimitri; Nicholas, the son of Dimo; Doncho, son of Nicholas; Dimo, the son of Nicholas; Stojan, the son of Nicholas; Dimo, his son; Nicholas, his son; Prokho, the son of Micho; Miho, the son of Kovac; Kraislav, his son; Belche, his son; Stale, son of Pando; Dimko, son of Pano; Pano, son of Kraislav; Todor, the son of Simon; Dimitri, son of Todop; Bojo, the son of Todor; Jorgo, son of Bele; Dujko, son of Bele; Mincho, son of Bela; Vasilko Hrano; Gorgo, the son of Projo; Stojan, the son of Nichola; Stanko, son of Stamat; Niko, son of Dobre; Pano, son of Stanko; Nicholas, son of Dimo; Pejo, son of Dimo; Kojo, the son of the Grupce; Nichola son of Prodan; Tomce, son of Vaco; widow Vida; Panno, the son of Dimo; Nichola, son of Pano; Petko, the son of Margari; Dobre, son of Nichola; Prodan, son of Ralgo; Widow Mara, Drajo’s wife; widow Gera; Ignorance, the gurus of Firoz, is married; Iljas, his son, Benak; Hasan, his brother, is not married; Umur, his brother, is not married.

List 594: Families – 45 Widows – 2

| Wheat, 33 (loads) value | 528 akcija (akçe) * | Aakçe – was the chief monetary unit of the Ottoman Empire, a silver coin. Three akçes were equal to one para. One-hundred and twenty akçes equalled one kuruş. |

| Barley, 41 (loads) value | 410 | |

| Rye 9 (loads) value | 90 | |

| Usur from Millet 4 (loads) | 40 | |

| Usur from Vineyards 160 medars value | 800 | |

| Usur from Flax | 847 | |

| Of 11 mills working half a year | 135 | |

| Pig Tax | 47 | |

| From Weddings | 30 | |

| From Deaths | 7 | Usually paid to the church |

| Usur of Honey | 10 | |

| Ushur of vegetables | 30 | |

| Arrival of 30 Hassas – Nuts and 15 Hassas – Mulberries | 60 | |

| Income from one hassa (facility) water mill that is now destroyed | 80 | |

| Muslim Land tax | 34 |

Income from those who process the land from the outside

| Wheat, 1 load | 16 |

| Rye, 1 load | 10 |

| Ushur from Flax | 49 |

| Millet 1 load | 10 |

Total Income – 3 233 akçe

- List Mezra MANAKO the mentioned Timar

- Part of the mezra Timar of Kalboroc

- Part of the mezra Timar of Potxor

A timar was land granted by the Ottoman sultans between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, with a tax revenue annual value of less than 20 000 akçes. The revenues produced from land acted as compensation for military service. A Timar holder was known as a Timariot. If the revenues produced from the timar were from 20,000 to 100,000 akçes, the timar would be called zeamet, and if they were above 100,000 akçes, the land would be called hass.

Part of the Village of Zelenic – the mentioned Timar

Rado, son of Stanko; Tomce, the son of Rado; Stoyan, the son of Rado; Marko, the son of Rado; Gorgo, son of Stojo; Stajko, son of Rado; Dimitri, son of Stajko; Kalko, son of Gorgi; Kojo, son of Prodan; Stojan, the son of Kojo; Projo, the son of Kojo; Radoslav, son of Kojo; Pejo, son of Kojo; Stojan, the son of Prodan; Rajko, son of Prodan; Simon, son of Rajko; Kojo, son of Todor; Dimitri, son of Comnen; Viromir, son of Matjo; Dobre, son of Rajko; Brajko, the son Gorgo; Nasto, the son of Kovac; Pejo, son of Rajko; Stale, the son of Andronik; Prodan, son of Grupce; Radoslav, son of Grupce; Bojko, son of Grupce; Todor, son of Dobre; Kojo, son of Doce (Tose); Dimo, son of Stale; Projo, son of Dimo; Todor, son of Petko; Stajko, son of Pano; Stamko, son of Pano; Gorgo Sarakin; Denko, his son; Rajko, son of Dobre; Pejo, son of Trajko; Bogdan, son of Igora; widow Ibra, wife of Doco; widow Stojna, wife of Bratan; Hussein, Gulam of Firuz, married; Hazir, his son, Benak.

Income from: 43 Families

| Wheat, 33 (loads) | 528 |

| Barley, 41 (cargo) | 410 |

| Ushur from flax | 889 |

| Ushur from the vineyards, 160 honey | 800 |

| Ushur from rye, 9 (loads) | 90 |

| Ushur of millet, 3 (loads) | 30 |

| 8 mills working Half a year | 135 |

| Ushur from the vegetable | 30 |

| The income of 35 hassa of nut | 36 |

| 15 hass of mulberries | 15 |

| Pig Tax | 50 |

| Wedding Tax | 14 |

| From Deaths | 7 |

| Ushur of honey | 10 |

| Ushur of Honey | 51 |

- From Mezrata Novaxop – the mentioned Timar – EMPTY

- Mezra Kalboroc – the mentioned Timar – EMPTY

- From Mezrata MANAKO – the mentioned Timar – EMPTY

Total Income: 3161 akçe

For some reason, according to oral history, the village of Zelenic never had to pay taxes. This cannot be corroborated and it is our opinion that there may have been some type of exemption due to the mix of Christians and Muslims living peacefully together. The Defter of 1481 supports the claim that the village started paying some type of tax and or military service was served by the Mulsim “Sipahi’s. By the late 1800’s one third of the population was Muslims and apparently they did not own land but worked for the Christians. The introduction of the Ciftlik system (16th & 17th centuries) was avoided by the village. According to oral history, the leaders of the village, both Christian and Muslim, gathered at “Black Water” (Tsrna Voda), the fork in the road that lead to Neveska (Nymfeo). Here the leaders met the Ottoman government officials bearing gifts and lobbying for the exemption from becoming a ciftlik. They convinced the government officials that since both Muslims and Christians lived in peace and harmony they should be exempt from becoming a ciftlik. The government officials then proceeded to go up the mountain to Neveska (Nymfeo) and made it a ciftlik.

Ciftlik: large agricultural lands organized as a production unit under a single ownership and management and usually producing for the market came into being mostly on mawat, i.e., waste or abandoned lands outside the areas under the cift-hane system. A typical ciftlik was small, no more than 2 or 3 units (household units) in size. Although consolidated, large ciftliks existed in export-oriented zones, these were most untypical.

Once they were found, the inhabitants of Zelenic had to endure the wrath of invading nomads, possibly Yoruks. These Muslim settlers were very few at first, but they were influential enough to force the people of Zelenic from the south-eastern side of the Lehovo river under Gradishta and Galabnic, to the north-western side just east of present day St. George’s church.

The Muslim settlers in Zelenic were originally displaced people who according to Turkish oral history, were expelled from Anatolia after the Battle of Ankara in 1402. The re-settlement of populations is a common occurrence which even took place during Philip of Macedon’s time when he moved people of different ethnicity to secure frontier lands. The practice was to move trouble makers from one location to a completely foreign site in order to quell rebellion or to put your most trusted allies as gate keepers in these new lands. This story was passed on by a Turkish person presently living in Izmir, Turkey. His grandfather told him of the story of Zelenic and how they were forced to leave the village as a result of the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey.

Sources:

- Chulev, B. (2016). THE SIEGE OF SVETIGRAD (‘Saint-city’) 1448/1449. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/30367090/THE_SIEGE_OF_SVETIGRAD_Saint-city_1448_1449.pdf

- Chulev, B. (2016). THE SIEGE OF SVETIGRAD (‘Saint-city’) 1448/1449. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/30367090/THE_SIEGE_OF_SVETIGRAD_Saint-city_1448_1449_matia.jpg

- Chulev, B. (2016). THE SIEGE OF SVETIGRAD (‘Saint-city’) 1448/1449. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/30367090/THE_SIEGE_OF_SVETIGRAD_Saint-city_1448_1449_Skanderbeg.jpg

- Inalcik, H. (1973). The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300-1660.

- Sokoloski, M. (1973). Turkish Documents: For the History of the Macedonian People: Extensive Census of the 15th Century. Skopje: Archive of Macedonia.

- Tomev, F. S. (1971). Short history of Zhelevo village, Macedonia. Toronto, Canada: Zhelovo Brotherhood_settlers.jpg

- Vakalopoulos, A. E. (1973). History of Macedonia, 1354-1833. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies.